In measure, however, history has repeated itself . . . . To all these places the oil derrick has come like a conquering army driving all before it. Farms, fields, orchards, gardens, dooryards, and even homesteads have been given over to the mad search for oil. In nearly all appear the same steps of progress; a lucky strike, the rush for leases, sudden wealth to the fortunate ones, boom towns, stock companies, and sooner or later the inevitable decline.[1]

I. INTRODUCTION

The State of Colorado owes a great deal to geology. Mining built the state out of its Rocky Mountains both literally and figuratively. Colorado would not be what she is today without her history of mineral extraction: from the gold and silver that drew prospectors to build the city of Denver and settle the most isolated reaches of the San Juans, to the coal that heated and powered a rapidly growing population.[2] The culture and economy of Colorado’s “Old West” were inextricably linked by the extraction of natural resources.[3] Over time, and with increased general prosperity, much of the Old West has faded as “New Western” economic industries and environmental values have blossomed.[4] Today a new resource boom is occurring in Colorado—the shale gas “revolution”[5]—and it has ignited new battles over the land and its mineral resources.[6]

Within just over a decade, developments in technology—particularly multi-stage slick-water hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”)[7] and horizontal or directional drilling—made previously unrecoverable hydrocarbon deposits profitable and vastly increased Colorado’s fuel mineral production.[8] This production surge has resulted in over 50,000 active wells in Colorado, sparking concern throughout the state about the impacts of oil and gas development.[9]

|

|

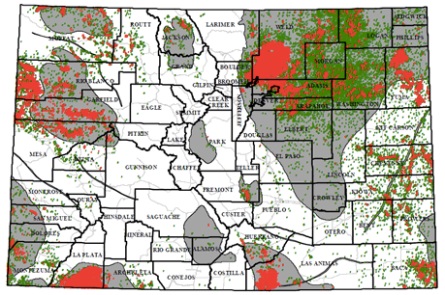

| Fig. 1. Colorado Natural Gas Production, 1960–2010.[10] | Fig. 2. Colorado’s Oil and Gas Basins.[11] |

Outside of federal lands, the federal government has generally left regulation of onshore petroleum development to the states.[12] In Colorado, the regulation of oil and gas production falls largely to one agency: the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (“COGCC”).[13] The COGCC’s primary mission is to “[f]oster the responsible, balanced development, production, and utilization of the natural resources of oil and gas . . . in a manner consistent with protection of public health, safety, and welfare, including protection of the environment and wildlife resources.”[14] The Oil and Gas Conservation Act (“OGCA”) provides that the COGCC “has the jurisdiction over all persons and property, public and private, necessary to enforce the provisions of this article, and may do whatever may reasonably be necessary to carry out the provisions of this article.”[15]

Colorado has always valued strongly empowered local governments, adopting municipal home rule into its constitution in 1902, only twenty-six years after achieving statehood.[16] Among their powers, local governments in Colorado have authority to regulate land use within their jurisdictions,[17] and several have recently acted to restrict oil and gas development (hereinafter “OGD”, or simply “development”).[18] Several localities/municipalities have enacted bans, moratoria, and regulations in an attempt to protect citizens and the environment from what many (although by no means all) have viewed as under-regulation by the state.[19] These efforts have been controversial and the focus of intense counter-efforts to override local authority in favor of a “uniform” state system.[20] The dispute over local OGD authority dates back to the late 1980s, when many rural, nonindustrialized communities began to see significant development activity for the first time. In 1992 two important cases were decided on the same day. These cases, referred to here as Voss and Bowen/Edwards,[21] while still good law, provide what is perhaps an outdated framework for balancing the current interests of state and local powers, industry, and twenty-first century New-Western communities.[22] This Article will focus on how the history of oil and gas regulation is being challenged to adapt to a new era where development is suddenly “booming” in large, heavily populated areas of the state.

Hydraulic fracturing and related technologies have unlocked vast reserves of natural gas in the Rocky Mountain region, providing the opportunity for lower energy costs, a transition away from heavily polluting coal, jobs, revenues, and the prospect of being a net energy exporter.[23] However, petroleum development has also heavily impacted local communities with impacts ranging from merely irritating to potentially dangerous, and is not always welcome. Perhaps most importantly, it has undermined the democratic respect for local control enshrined in the Colorado Constitution.

II. A BRIEF HISTORY OF STATE OIL AND GAS REGULATION

The discovery of petroleum and its rise as a dominant energy source has been fraught with discord and concerns about scarcity nearly since the first commercial oil well was drilled.[24] In 1924, one scholar noted, “fears are increasingly felt. Will it be possible to satisfy the dizzy increase in consumption of oil? And do not certain countries already fear to see the reserves contained in their soil exhausted?”[25] In addition to the “dizzy increase in consumption,” fundamental problems with extraction alarmed producers. At the end of the nineteenth century the market was controlled not by regulation but by increasing monopolization; established in 1870 by John D. Rockefeller, Standard Oil had acquired ninety percent of the market by 1904.[26] The federal government responded with antitrust actions that culminated in the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911.[27] This shocking event caused oil producers to harbor a long-lasting distrust for the federal government[28] and unleashed competition into an unregulated industry where a lack of property rights created perverse incentives. In the pre-regulatory era developers operated under the “law of capture,” under which landowners had no legal property right until the oil was extracted.[29] Landowners had to drill wells and race to extract before neighbors could drain their interest: this is known as the ‘Offset Drilling Rule.’[30] Waste—both physical and economic—was rampant as often-inexperienced producers cut corners to obtain their share before it flowed away underground, encouraged by mineral lease contracts construed to promote development and prevent delay.[31]

Between 1916 and 1926, it became clear that the law of capture was inadequate to equitably apportion or administer rights in common pools.[32] A counter-balancing doctrine—the doctrine of ‘correlative rights,’ which formed the basis for later conservation efforts—was recognized by the Supreme Court in 1900, but did not greatly influence the legal framework of production at the time.[33] Regulation (also called conservation) would be necessary to control production and end the industry-defeating price depressions and the unfairness of the common-pool depletions.

A. Regulation of Oil Extraction Before 1935

States came to dominate the regulation of oil and gas production, but this was not an inevitable result. The federal government attempted to impose regulations on oil production in 1924 when President Coolidge created the Federal Oil Conservation Board (“FOCB” or “the Board”).[34] This occurred during the Lochner Era, when the Supreme Court narrowly interpreted the Commerce Clause to limit Congress’s power to regulate industrial production.[35] In its first report, the Board concluded that the lack of a general police power limited federal regulation to oil production on federal lands and for national defense.[36] In its fifth and final report in 1932, the Board declared that states would need to cooperate and coordinate to enact regulation, a solution much favored by industry.[37] While pro-conservation forces worked to move federal regulation forward, oil interests attempted to avoid federal oversight by discrediting the notion that oil was being ‘wasted’ and by imposing self-regulation measures.[38]

By the early 1930s there was an American oil crisis.[39] Overproduction of newly discovered oil fields caused oil prices to fall from around a dollar per barrel to fifteen cents, and then to ten cents per barrel.[40] The situation was dire enough that oil fields were closed, martial law was imposed, and National Guard troops called to keep the peace in East Texas and Oklahoma oil fields in 1931.[41]

In response, and in an effort to forestall the threat of federal regulation and to keep oil prices high, oil-producing states pushed hard on the federal government to allow the states themselves to regulate the production of oil and adopt various oil conservation measures.[42] In March of 1931, the Oil States Advisory Committee, representing seven oil-producing states, agreed to a framework for interstate cooperation.[43] In a letter to the FOCB, the members asked for each state to retain its own administration, in cooperation with the other oil-producing states through an interstate advisory board.[44] The FOCB, in its fifth and final report, called for the immediate creation of an interstate compact to coordinate the regulation of oil and gas production.[45]

Before the issues of interstate compacts and state commissions were settled, an important case involving one of the first state conservation measures tested the ability of local governments to enact protective regulations that would prevent the development of oil and gas. Oklahoma City enacted a local ordinance requiring a bond of $200,000 per well drilled in the city,[46] and sought an injunction against drillers who did not provide the bond. In Gant v. Oklahoma City, operators (also known as developers) sought to enjoin the ordinance on the grounds that exclusive control of drilling had been placed in the hands of the Corporation Commission, a state agency charged with regulating the conservation of petroleum, drilling of wells, and the operation of pipelines.[47] The Oklahoma Supreme Court found that nothing in the grant of authority to the Commission deprived the city of its police power and that,

[a]s a property protection, the city was endowed with the power of regulation. But there is something far greater than property involved in this case; it is the safety of human life and health . . . . We have on one side the people that want money, and on the other side the people that want life, and its enjoyment in the home already provided.[48]

The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the holding in Gant as neither violating due process, nor arbitrary or unreasonable, and the city’s bond requirement was upheld.[49]

Between 1932 and 1935, chaos ensued as the FOCB dissolved, the Oil States Advisory Committee collapsed, and state conservation commissions, notably the Texas Railroad Commission, failed to impose regulations that were either heeded by producers or upheld by the courts.[50] In 1933, President Roosevelt signed the National Industrial Recovery Act (“NIRA”), as part of his New Deal legislation, which allowed the federal government to create regulated cartels and monopolies.[51] However, after the constitutional invalidation of the NIRA in May of 1935,[52] the door was open for the states to resume control over conservation regulation.[53]

B. The Conservation Era in Colorado

In February 1935 nine oil-producing states met in Dallas, Texas.[54] With the decision looming in Schechter Poultry Corp. and potential for chaos with the invalidation of NIRA, these would-be regulators finalized an Interstate Compact to Preserve Oil and Gas and became the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission (“IOGCC”).[55] Colorado ratified and adopted the compact in April the same year,[56] prior to ratification by the U.S. Congress in August 1935.[57] While the Compact did not contain binding orders or regulations, each state agreed to pass laws, enact regulations, and create programs to conserve oil and gas, prevent waste, and maximize recovery.[58]

Colorado’s first conservation agency—the Gas Conservation Commission (“GCC”)—was established in 1927 as part of the division of conservation under the executive department.[59] The GCC was to “adopt reasonable rules and regulations as may be proper for the conservation of the gas resources of the state and the prevention of gas waste,” with penalties of “not less than fifty dollars and not more than one hundred dollars [for] each day’s violation . . . .”[60] The GCC repealed several oil and gas statutes, including: portions related to record keeping for drilling and well abandonment; a 1915 law prohibiting natural gas venting; and two 1929 laws requiring the plugging of abandoned wells, and established penalties for violating well abandonment laws. [61] Before the 1929 laws were repealed, the penalties for violating well abandonment laws were set at “not more than one thousand dollars, or by imprisonment of not more than six months in the county jail, [or both]” for “any violation.”[62] In 1951 the Colorado General Assembly adopted the Oil and Gas Conservation Act (“OGCA”).[63] At the time, the major issue facing Colorado oil and gas production was the need to promote industry in the face of relatively scant recoverable petroleum resources. The OGCA created the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (“COGCC”), replacing the GCC.[64] The new Commission consisted of five members. Four members with at least five years of industry experience were to be appointed by the governor, the fifth member was the State Oil Inspector.[65] None of the members received compensation for their performance as members of the COGCC.[66] The Commission was charged with preventing waste;[67] was granted authority to promulgate rules and to enjoin violations; and was given jurisdiction over “all persons and property, public and private, necessary to enforce the provisions of this Act.”[68]

By 1970 U.S. production of oil reached its apex.[69] Suddenly, under the combined effects of federal import policies, global upheaval, and an oil embargo from OPEC, a crisis in the U.S. oil supply occurred in the first half of the 1970s.[70] Relaxed controls on production by the compacting states were insufficient to mitigate the sudden reduction in supply to prevent economic shock.[71] The passing of the Clean Air Act (1963, strengthened in 1970), the National Environmental Policy Act (1970), and the Clean Water Act (1972) altered the relationship between the IOGCC, member states, and production. The new goal of state ‘conservation’ was an all-ahead maximization of production, which included political efforts to push against the application of federal environmental regulation and to obtain federal support for production and research. The IOGCC’s lobbying efforts successfully obtained exemptions from federal price controls and environmental regulations,[72] and obtained billions of dollars for research into hydraulic fracturing and related technologies.[73] IOGCC’s efforts continue to this day. Most recently, then IOGCC chair Alaska Governor Frank Murkowski championed the passage of the 2005 Energy Policy Act, a federal action that unleashed new growth potential for the use of hydraulic fracturing through exemption from certain environmental protections.[74]

Today, federal environmental laws contain many exemptions for OGD,[75] and have been far less controlling of OGD than other heavily polluting industries.[76] Many OGD chemicals, processes, or wastes have been given special treatment under federal legislation, including the Clean Water Act (“CWA”),[77] the Safe Drinking Water Act (“SDWA”),[78] the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (the federal hazardous-waste disposal law),[79] and the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (“CERCLA,” or “Superfund”) which imposes liability on polluters.[80] Some sources of OGD air pollution are exempt from regulations under the Clean Air Act,[81] and the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) does not require the oil and gas industry to report the release of its toxic effluents or emissions to the Toxic Release Inventory under the Emergency Planning and Community Right to Know Act (“EPCRA”).[82]

Even the Oil Pollution Prevention Act contains exclusions for hydraulic fracturing, and applies only where “oil is discharged, or . . . poses the substantial threat of a discharge . . . .”[83] That act excludes federally permitted releases, and covers only the release of oil (excluding gasses, fracking fluids, flowback, or other wastes) into “navigable” waters—it does not apply to releases onshore or from onshore facilities.[84] Finally, certain natural gas facilities are the subject of targeted “categorical exclusions” under the National Environmental Policy Act (“NEPA”), which imposes a ‘rebuttable presumption’ against environmental review.[85]

Although the federal government directly controls petroleum pipelines, offshore production,[86] and development on public lands,[87] recent catastrophic events have cast doubt upon its willingness and ability to regulate producers.[88] The EPA has expressed a renewed (if belated) interest in increasing federal regulation of OGD, and has enacted new regulations requiring certain air pollution-control measures to prevent venting of untreated gasses to the atmosphere by 2015,[89] and to improve performance standards for storage tanks regarding emissions of volatile organic compounds.[90] The EPA is also considering requiring the disclosure of the chemicals used during fracking.[91]

III. LOCAL REGULATION OF OIL AND GAS IN COLORADO

Local governments have been in a regulatory fight to enact restrictions on development in Colorado since the 1980s, when conventional development began to encroach on both populated and undeveloped areas.[92] Until 2007, a majority of the COGCC Commissioners were also members of industry (by statute), and the state seemed happy to pocket the economic benefits of the pro-industry regulation that resulted. Cities and counties, having extremely limited or no procedural rights at the Commission, have attempted numerous regulations or bans some of which have been upheld by courts.[93] However, while the legislature rewrote much of the OGCA to increase the Commission’s authority and duty to protect public health and the environment, and reduce the mandate to foster development and prevent waste as well as industry influence within the COGCC, the COGCC, the Governor, and the State Attorney General have used these developments to attempt further expansion of state control by interpreting state powers broadly and state responsibilities narrowly.[94]

A. Local Governmental Powers & Limits of Authority

At the end of the nineteenth century, municipalities were widely viewed as mere agents for state government, and were dependent on state legislation to control or delegate control of local activities. Under the common law doctrine of “Dillon’s Rule,” municipalities had no inherent sovereignty or police powers outside of those delegated by the state.[95] Local authority was limited to powers explicitly or impliedly conferred by the legislature.[96] During this era reformers felt that,

[I]t was a period of disintegration, waste, and inefficiency. Political machines and bosses plundered many communities. Lax moral standards of the times in business life, the apathy of the public, and general neglect of the whole municipal problem by leading citizens, by the press, and by the universities, all contributed to the low state of city affairs.[97]

The “home rule” movement found root in Colorado at the turn of the century, in part because the citizens of Denver chafed under state control of their municipality—particularly state appointed boards in charge of public works, fire, and police.[98] This tension nearly led to armed conflict between the city and the state in 1894.[99]

As noted by the Colorado Supreme Court, in one of the earliest cases on the point, “[t]he right of self-government in cities and towns is coeval with the history of the Anglo-Saxon race. It was confirmed by Magna Charta to cities and boroughs.”[100] Quoting language from two other state courts, the Colorado Supreme Court directed that:

Written constitutions should be construed with reference to and in the light of well-recognized and fundamental principles lying back of all constitutions, and constituting the very warp and woof of these fabrics. A law may be within the inhibition of the constitution as well by implication as by expression.

* * *

‘Courts, at least, are bound to respect what the people have seen fit to preserve by constitutional enactment, until the people are unwise enough to undo their own work. The loss of interest in the preservation of ancient rights is not a very encouraging sign of public spirit or good sense.’ Such a statement is very pertinent at this time, when both federal and state government[s] are constantly encroaching upon the right of local self-government.[101]

Importantly, the court in Town of Holyoke v. Smith found that while the state may exercise its police power within a city, it may not delegate those police powers.[102] Article V § 35 of the Colorado Constitution prohibits the delegation of municipal functions to state commissions, corporations, or associations.[103] Counties may also qualify as “municipal” for the purposes of this nondelegation doctrine.[104] The purpose of this amendment was specifically to “prevent intrusion upon a municipality’s domain of local self-government.”[105] Regarding the importance of upholding the constitutional spirit, the court quoted:

Narrow and technical reasoning is misplaced when it is brought to bear upon an instrument framed by the people themselves, for themselves, and designed as a chart upon which every man, learned and unlearned, may be able to trace the leading principles of government. The Constitution is to be construed as a frame of government or fundamental law, and not as a mere statute.[106]

1. Constitutional Home Rule in Colorado

The Colorado Constitution empowers municipalities to become “home rule” jurisdictions.[107] Home rule municipalities have jurisdictional sovereignty equal to but separate from the state,[108] with the “police power” to regulate local issues without specific statutory authorization from the state.[109] This constitutionally empowered form of governance contrasts with “statutory” municipalities, whose powers are limited to express or implied delegation of legislative authority from the state. Home rule, with its expansive regard for the power of local governments, has always appealed to the citizens of Colorado and much less so to the state government.[110]

By constitutional amendment, Colorado’s citizens adopted municipal home rule in 1902 “for the purpose of creating the consolidated city of Denver and establishing that city’s independence from state legislative control of its affairs.”[111] In 1912, the voters strengthened the new independence of municipalities by amending the home rule provision to “grant and confirm to the people of all municipalities . . . the full right of self-government in both local and municipal matters and the enumeration herein of certain powers shall not be construed to deny such cities and towns, and to the people thereof, any right or power essential or proper to the full exercise of such right.”[112] Municipal home rule was expanded in 1970 to allow municipalities to adopt home rule regardless of their size.[113] The Colorado Supreme Court has interpreted these constitutional powers broadly, holding that “the power of a municipal corporation should be as broad as possible within the scope of a Republican form of government of the State.”[114] Obviously, home rule does not assist in the uniform administration or operational efficiency of the state, nor was it ever intended to. Home rule is intended to uphold the most ancient foundation of our political beliefs: that sovereignty lies with the people, it is not delegated to people by the state.[115]

The power of home rule municipalities is exclusive over local concerns—the state may not impose its will.[116] Under Colorado law, however, the state may preempt home rule regulations where there is a significant “state interest” involved. Where a matter encompasses both local and statewide interests, home rule municipalities may enact a regulation that does not “operationally conflict” to the extent that it “materially impedes or destroys a state interest,”[117] although both may be valid if they can be harmonized.[118] Contrary provisions do not necessarily create such a conflict, and they should be reconciled and each given effect if possible.[119] Where the state interest is dominant, even home rule municipalities may not regulate in the absence of specific state constitutional or statutory authorization.[120]

The Colorado Supreme Court has articulated four factors to determine what constitutes a local versus a statewide concern: (1) whether there is a need for statewide uniformity of regulation; (2) whether the local regulation could create “extraterritorial” effects beyond the borders of the local jurisdiction; (3) whether there is a traditional or historic exercise of control; and (4) whether the state constitution explicitly vests authority over an issue at the state or local level.[121] This is not meant to be exhaustive, but to act as guidance for “a process that lends itself to flexibility and consideration of numerous criteria.”[122] Colorado courts have upheld local regulations with extraterritorial impacts,[123] have noted “uniformity in and of itself is not a virtue,”[124] and have weighed the relative local and state-asserted interests in order to find that some local interests trump other state interests.[125] The courts have wide leeway to determine whether there is a state or local interest “depend[ing] on the time, circumstances, technology, and economics.”[126]

It was not until 1972 that the legislature granted Colorado counties home rule authority over their unincorporated (nonmunicipal) territory.[127] The state legislature enacted the Colorado County Home Rule Powers Act in 1981,[128] to expand the powers of home rule counties.[129] Still, the powers of home rule counties are far less encompassing than that of home rule municipalities, as counties are given only a “structural” home rule—the power to change the structure of their self-governance—and do not have the additional “functional” home rule granted to municipalities.[130] Therefore, home rule counties have fewer inherent powers than home-rule municipalities, and require enabling legislation from the state similar to that required by statutory municipalities.[131]

2. Enabling Legislation for Local Government Regulation

For statutory municipalities and all counties, enabling legislation is required to enact regulations to control land use and other incidents related to oil and gas. Colorado has enacted a number of statutes empowering local governments to create comprehensive plans, zoning and land-use regulations.[132] Unlike some other states, Colorado does not have a statewide land-use plan, but leaves the majority of land-use planning to local governments.[133] County land-use regulatory authority in Colorado derives from three statutes: the County Planning Act, the Local Government Land Use Control Enabling Act (“Land Use Enabling Act”), and the Areas and Activities of State Interest Act (“AASIA”).[134] Statutory cities are empowered under Colo. Rev. Stat. § 31-15-101 (2012).

The County Planning Act was first enacted in 1939, to broadly empower boards of county commissioners to “provide for the physical development of the unincorporated territory within the county and for the zoning of any part of such unincorporated territory.”[135] Under the County Planning Act, a county may adopt zoning resolutions to regulate land uses to promote the “health, safety, morals, convenience, order, propriety, or welfare of the present and future inhabitants of the state,”[136] and may adopt a land-use master plan for its unincorporated territory.[137]

After a population boom in the 1960s, during which Colorado grew by over twenty-five percent,[138] local governments complained to the legislature that their existing powers were inadequate to deal with land-use conflicts.[139] The Land Use Enabling Act was enacted with the recognition that “rapid growth and uncontrolled [human] development may destroy Colorado’s great resource of natural, scenic, and recreational wealth.”[140] Finding that local authority needed to be expanded, the legislature provided that “the policy of this state is to clarify and provide broad authority to local governments to plan for and regulate the use of land within their respective jurisdictions.”[141] The Land Use Enabling Act allowed local governments to control and plan for growth related land uses, including “protecting lands from activities that could pose an immediate or foreseeable material danger to significant wildlife habitat,”[142] regulating land uses that might “impact . . . the community or surrounding areas,”[143] and “[o]therwise planning for and regulating the use of land so as to provide planned and orderly use of land and protection of the environment in a manner consistent with constitutional rights.”[144] Under the Land Use Enabling Act, Counties are “provide[d with] broad authority” to “plan for and regulate the use of land within their respective jurisdictions.”[145] However, local governments may not “diminish the planning functions of the state,”[146] and if the state has enacted “other procedural or substantive requirements for the planning or the regulation of the use of land, such requirements shall control.”[147]

The AASIA was created the same year to clarify the boundary of state and local jurisdiction over matters of statewide interest, and improve the quality of local development (including non-oil and gas related development) through increased state oversight.[148] It gave local government so called “1041 Powers,” named for H.B. 1041 that created the AASIA.[149] The AASIA ensured that local authorities could consider and mitigate the impacts of new developments, even those that affect areas or activities of state interest.[150] Local governments can designate an activity or area to be one of state interest, in which case they may halt the project until reviews are conducted, and although they would then be forced to use minimum state regulations, they may also choose more stringent regulations.[151] Some examples of activities that a local government might want to designate would be the site selection for airports, highways, or sewage treatment plants.[152] Mineral resource areas may be designated, and, if a local government finds that mineral “extraction and exploration would cause significant danger to public health and safety,” it need not devote the area to mineral development, and if “the economic value of the minerals present therein is less than the value of another existing or requested use, such other use should be given preference . . . .”[153] In 2004 the Department of Local Affairs reviewed local 1041 regulations and found that approximately half of Colorado’s counties were regulating ‘mineral resource areas.’[154] However, 1041 powers are limited in their authorization for local control over oil and gas development: the COGCC must agree to new designations of oil and gas areas of state interest, unless it includes all or part of another area of state interest.[155]

The legislature delegated police power to statutory municipalities to enact “ordinances not inconsistent with the laws of [the] state,” where “necessary and proper to provide for the safety, preserve the health, promote the prosperity, and improve the morals, order, comfort, and convenience of such municipality and the inhabitants thereof.”[156] The statute was amended in 1975 to clarify and guide the use of municipal powers.[157] Statutory municipalities also have zoning authority;[158] however, this is narrower than the zoning authority granted to counties.[159] Several Colorado statutes give local governments regulatory authority to protect the environment and public health, including the power to enact air pollution regulations,[160] and to declare what is a nuisance.[161]

Although home rule municipalities possess more regulatory power than other forms of local government, the preemption test for home rule and statutory municipalities and counties is currently the same: whether there is “operational conflict” to the extent that it “materially impedes or destroys a state interest.”[162] The regulation of oil and gas has been found to be of mixed state and local interests, and neither expressly nor impliedly preempted by statute.[163]

B. Development of The Ad Hoc Conflict Preemption Test

In the 1980s, when the fight between the state and local governments over regulation of oil and gas began, the statutory mandate of the COGCC was:

[T]o promote the development, production, and utilization of the natural resources of oil and gas in the state; to protect public and private interests against the evils of waste; to safeguard and enforce the coequal and correlative rights of owners and producers in a common source or pool of oil and gas so that each may obtain a just and reasonable share of production therefrom; and to permit each oil and gas pool to produce up to its maximum efficient rate of production subject to the prohibition of waste and subject further to the enforcement of the coequal and correlative rights of commons-source owners and producers to a just and equitable share of the profits.[164]

It was not until 1985, after Douglas County attempted to restrict development, that the General Assembly amended the OGCA to explicitly require the COGCC to “promulgate rules and regulations to protect the health, safety, and welfare of the general public in the drilling, completion, and operation of oil and gas wells and production facilities.”[165]

1. Oborne v. Board of County Commissioners of Summit County

In the mid-1980s, Douglas County enacted regulations requiring oil and gas developers to obtain special use zoning permits, which would be determined by the Board of County Commissioners after a public hearing.[166] In addition to specific permitting criteria, the measure allowed the Board to impose additional conditions not required by the zoning resolution.[167] The Board denied Harry Oborne and Anthony Allegreti’s permit for three wells because they refused some conditions required by the Board, including immediate reclamation, a bond to cover potential costs to the County, assurances that spills would not impact downstream water users, a fire protection plan, and cement casing of the well to the base of the water supply.[168] Oborne and Allegreti sued the County, claiming that COGCC’s authority to regulate OGD preempted Douglas County’s zoning ordinance.[169] The district court concluded that none of the conditions and requirements imposed by the Board were “proper land use considerations,” but pertained to “conduct of the drilling operations” regulated exclusively by the COGCC, reversed the denial of the permit and remanded to the Board.[170] The County appealed the district court’s decision.[171]

Oborne entered the courts before the 1985 amendments, when the stated purpose of the COGCC was to “encourage the development, production, and utilization of the natural resources of oil and gas . . . to prevent waste, and to allow each owner of an interest in an oil or gas pool to obtain an equitable share of the pool’s production.”[172] The court of appeals found that the COGCC had adopted expansive regulation under its authority, and decided that by enacting the OGCA, the legislature intended “to vest in the Commission the sole authority to regulate those subjects addressed by the Act and bar any local regulation concerning those subjects.”[173] It contrasted the OCGA with the Mined Land Reclamation Act, which required permittees to show they had complied with all local laws, instructing the state to deny permits if the operation would be in conflict with county zoning or subdivision regulations—provisions not contained within the OGCA.[174]

In 1985, while Oborne was still being decided, the state General Assembly adopted an amendment to the OGCA requiring the COGCC to promulgate regulations “to protect the health, safety, and welfare of the general public in the drilling, completion, and operation of oil and gas wells and production facilities.”[175] The Oborne court asked the County to “provide . . . their views as to whether this provision left any room for local legislation, or for the requirement of a local permit.”[176] The County conceded that “it no longer [had] any basis to continue to deny . . . their right to make use of their leasehold interest . . . .”[177] Whether or not the legislature intended the result, the amendment had the effect of expanding the issues subject to state preemption by the state.

The court of appeals remanded the case and directed the district court to remand it to the County with instructions to issue the well permits.[178] Oborne represents the high water mark for state preemption of local oil and gas regulations because it found that the COGCC had field preemption to promulgate OGD rules, including health and safety rules.[179] However, while Oborne was never explicitly overruled, in Bowen/Edwards the Colorado Supreme Court narrowly construed the 1985 OGCA provisions to apply only to the technical aspects of drilling, and failed to grant broad authority to regulate for health, safety and welfare.[180] No later case has supported the field preemption theory advanced in Oborne.

2. Voss v. Lundvall Brothers and Board of County Commissioners v. Bowen/Edwards

Two cases, Voss v. Lundvall Brothers (“Voss”),[181] and County Commissioners v. Bowen/Edwards and Associates (“Bowen/Edwards”),[182] articulate the current scope of state preemption in OGD regulation. Together, these two cases hold that while state delegation of certain regulatory powers preempted local regulations that “operationally conflict” with state regulations, there is no “overriding state interest” or field preemption. Instead, operational conflict must be decided in each case on a developed evidentiary record, or “ad hoc” basis.[183] Thus, these cases implicitly overrule Oborne’s field preemption finding, and make room for both counties and home-rule municipalities to exercise their regulatory powers in the oil and gas context.[184]

Bowen/Edwards came to the court of appeals after an oil developer brought a facial challenge to La Plata County oil and gas permit regulations.[185] Finding it could resolve the legal issue of preemption without first remanding the case for development of a factual record, the court held that “[t]he [Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation] Act is a legislative intent to occupy the field of oil and gas regulation. Sole authority to regulate that area is vested in the [COGCC], and any local regulation addressing the subject is barred.”[186] In addition, the court did not make any distinction between technical aspects of drilling, operation, and production on the one hand, and land use on the other. It found that the Colorado legislature had created field preemption by giving the COGCC “broad authority to regulate all phases of oil and gas development, including regulation of the impact of such development on the surrounding community.”[187]

In a momentous turn, the Colorado Supreme Court took up Bowen/Edwards to overturn the holding of the court of appeals.[188] Disagreeing with the lower court’s holding on preemption, the court found that local jurisdictions were not preempted with regard to their traditional powers over local land-use issues: “The state’s interest in oil and gas activities,” the court stated, “is not so patently dominant over a county’s interest in land-use control, nor are the respective interests of both the state and the county so irreconcilably in conflict, as to eliminate by necessary implication any prospect for a harmonious application of both regulatory schemes.”[189] Because the Colorado Supreme Court found that conflict preemption, rather than field preemption, would decide the validity of local regulation, Bowen/Edwards primarily stands for the proposition that operational conflict questions must be resolved on an ad hoc basis using a fully developed evidentiary record.[190]

The Colorado Supreme Court in Bowen/Edwards held that the effect of the 1985 amendments to the OGCA was simply to regulate the technical aspects of OGD to minimize the risk to the public.[191] As discussed at length by the Colorado Supreme Court in Bowen/Edwards, that provision was enacted to give the Commission the rulemaking authority to protect the public from such hazards as leaks, blowouts, or explosions, and “nothing in the statutory text . . . or[,] for that matter, in the legislative history . . . evinces a legislative intent to preempt all aspects of a county’s land-use authority over land that might be subject to oil and gas development or operations.”[192] As noted by the court, “[a] legislative intent to preempt local control over certain activities cannot be inferred merely from the enactment of a state statute addressing certain aspects of those activities.”[193] Indeed “[t]he state’s interest in uniform regulation . . . does not militate in favor of an implied legislative intent to preempt all aspects of a county’s statutory authority to regulate land use within its jurisdiction merely because the land is an actual or potential source of oil and gas development and operations.”[194]

The same day it decided Bowen/Edwards, the Colorado Supreme Court issued the companion case of Voss v. Lundvall Bros.[195] There, the home-rule City of Greeley enacted two nearly identical ordinances banning oil and gas well drilling within the city.[196] Lundvall Brothers, a Colorado oil company, obtained drilling permits from the city and the COGCC shortly before (and subsequently invalidated by) the passage of these ordinances.[197] Both the trial court and the court of appeals sided with the developer, holding that the OGCA reflects an overriding state concern with uniformity in regulation of OGD that left no room even for home rule cities to exercise traditional land-use authority.[198] The Colorado Supreme Court affirmed the court of appeals decision, but not its field-preemption reasoning.[199] Instead, it held that the powers of a home-rule city to control OGD encompassed matters of both local and statewide concern, and that since conflict preemption applied to matters of ‘mixed’ concern, a total ban on drilling would be invalidated by its inherent conflict with state regulations.[200] Using the four-part test, the court examined the local ban.[201] First, the court found that “primarily” due to the “pooling nature” of oil, the technological limitations on well placement, and consequent potential for extraterritorial effects, “the need for statewide uniformity of regulation of oil and gas development and production . . . weighs heavily in favor of state preemption of Greeley’s total ban . . . .”[202] Furthermore, the court found that the state traditionally had been the regulator of OGD (although it did not, traditionally, override local land-use authority).[203] The court noted that the state constitution neither committed OGD regulation solely to the state, nor land-use control to local governments.[204] Therefore, according to Voss, local governments retain their land-use authority in the OGD context “only to the extent that the local ordinance does not materially impede . . . significant state goals . . . .”[205]

At the time of Voss, drilling locations were restricted to directly above very specific portions of the target formation, and the target formations were those of pooling oil. “Oil and gas are found in subterranean pools, the boundaries of which do not conform to any jurisdictional pattern. As a result, certain drilling methods are necessary for the productive recovery of these resources.”[206] “The extraterritorial effect of the Greeley ordinances,” the court noted, “also weighs in favor of the state’s interest in effective and fair development and production, again based primarily on the pooling nature of oil and gas.”[207] Today, advances in drilling technology allow for directional and horizontal drilling of up to two miles underground, allowing recovery from wells that are sited more optimally for surface features.[208] Furthermore, today’s target formations to be fracked are largely impermeable (thus necessitating the fracturing of the rock), and therefore do not “flow.”[209]

As noted by the Colorado Supreme Court in Town of Frederick v. NARCO, the Colorado constitution forbids the General Assembly from delegating any municipal authority to a state commission such as the COGCC.[210] Land use, zoning, and regulation related to industrial are quintessentially local and municipal matters.[211] In Voss, the Colorado Supreme Court dismissed the notion that the OGCA intruded on municipal functions in violation of the Colorado Constitution’s Article 5 Section 35 because the court found that OCGA was not “directed to municipal land use but rather to the effectuation of the state’s legitimate concern for the efficient and fair development and production of oil and gas resources within the state.”[212]

C. Legislative and Judicial Developments Subsequent to Voss and Bowen/Edwards

In 1994, two years after the decisions in Voss and Bowen/Edwards, the legislature amended the OGCA to include “protection of public health, safety, and welfare” as a consideration of the Commission while it promotes, fosters, and encourages development and production.[213] These amendments added a seventh member to the COGCC, and increased the required number of members who are not employed by the oil and gas industry from one to two, while still requiring that the remaining five “shall be individuals with substantial experience in the oil and gas industry.”[214] The amendments required the Commission to regulate oil and gas operations “so as to prevent and mitigate significant adverse environmental impacts on any air, water, soil, or biological resource . . . to the extent necessary to protect health, safety, and welfare, taking into consideration cost-effectiveness and feasibility.”[215] Also, the amendments required the COGCC to “promulgate rules to ensure proper reclamation of the land and soil affected by oil and gas operations.”[216]

In Bowen/Edwards, the Colorado Supreme Court found that the language in the 1985 amendment gave the COGCC authority only to develop the technical safeguards necessary to minimize the risk from production operations.[217] The 1994 amendment gave COGCC authority to promulgate rules and regulations to protect the public “in the conduct of oil and gas operations.”[218] Just as in 1985, the state used this new language to claim that COGCC’s authority preempted local rules, despite the legislature’s normative instruction that “nothing in this act shall be construed to affect the existing land use authority of local governmental entities.”[219] This time, however, the courts disagreed. The Colorado Court of Appeals, in the cases of Town of Frederick v. NARCO, Gunnison County. v. BDS International, and La Plata County v. COGCC, affirmed that local governments retained their authority to regulate OGD, as long as such regulations could be reconciled with state law.

1. Town of Frederick v. North American Resources Company

In 2002, the Colorado Court of Appeals decided a case in which the North American Resources Company (“NARCO”) challenged the Town of Frederick’s oil and gas regulations.[220] The Town of Frederick is a small statutory municipality.[221] The disputed local ordinance prohibited the drilling of oil or gas wells without a special use permit.[222] The permit required a $1,000 application fee; contained specific requirements for well location, setbacks, and nuisance impact mitigation; and authorized the town attorney to bring an action to enjoin, remove, or impose penalties for noncompliance.[223] NARCO obtained the required state COGCC permits, but the town brought suit after NARCO began operations without applying for the town special use permit.[224] The trial court struck down several provisions in the Town of Frederick’s ordinance, upheld others, issued an injunction, and awarded attorney’s fees to the town.[225] At the Colorado Court of Appeals, the central question was whether a statutory municipality had the power to enact regulations aimed at oil and gas production within its jurisdiction.[226]

NARCO argued that the 1994 OGCA amendments expanded state preemption to preclude any local regulation of oil and gas.[227] The trial court found that the amendments did not “compel such a conclusion,” and noted that the amendment contained a statement that “nothing in this act shall be construed to affect the existing land use authority of local governmental entities.”[228] Additionally, the court noted that in 1996 the legislature one again amended the OGCA to authorize local governments to charge a “reasonable and nondiscriminatory fee for inspection and monitoring for road damage and compliance with local fire codes, land use permit conditions, and local building codes.”[229] According to the court, “the General Assembly anticipated that local governments could issue land use permits that included conditions affecting oil and gas operations [and] . . . did not intend to preempt all local regulation . . . .”[230] New COGCC regulations, the court said, could potentially create operational conflicts that would invalidate irreconcilable local regulation, but that the statutory changes did not preclude local regulation per se.[231]

NARCO also claimed that language in Bowen/Edwards declared that technical aspects of siting, drilling, and operation of production facilities were activities that required uniform state regulation, and that therefore the Town ordinance was wholly preempted.[232] The court dismissed the claim, noting that “[t]he Bowen/Edwards court did not say that the state’s interest ‘requires uniform regulation of drilling’ and similar activities,” rather, only the “technical aspects” of drilling and similar activities.[233] The court then held that the town’s regulations, “such as those governing access roads and fire protection plans,” did not “regulate technical aspects of oil and gas operations.”[234] The court noted that the Town’s regulations might be preempted if an actual conflict with COGCC regulations persisted.[235]

After dismissing NARCO’s arguments, the court found that, under the operational conflict test established by Bowen/Edwards and Voss, local regulations relating to any technical aspect of drilling, setback, noise abatement, or visual impacts were preempted, including the town’s fine for violations.[236] After NARCO, what remained of the town ordinance were building permit requirements for aboveground structures, access road maintenance requirements, fire and emergency planning requirements, the ability to require new buildings to be set back from existing wells, and the ability to enjoin violations.[237]

|

|

| Fig. 3. Pump jack next to homes in Frederick, CO.[238] | Fig. 4. Drilling rig set up near subdivision in Frederick, CO.[239] |

2. Board of County Commissioners of Gunnison County v. BDS International, LLC

At roughly the same time as NARCO was moving through the courts, Gunnison County brought a case against BDS International for violating local oil and gas regulations.[240] The COGCC intervened to defend the oil company, and moved for summary judgment on the basis that the county regulations were preempted.[241] The trial court agreed, holding that numerous county ordinance provisions facially conflicted with state law.[242] The Colorado Court of Appeals found that the trial court erred, in part, by failing to develop the evidentiary record required by the ad hoc rule in Bowen/Edwards.[243] The court rejected the notion that “same subject” regulation by local governments was necessarily preempted, under both Bowen/Edwards and NARCO.[244] The court upheld the trial court’s facial determination that fines, mitigation costs, and bonds were solely regulated by the COGCC, and that access to operator records could be limited to the COGCC and its agents.[245] However, the court determined that an evidentiary record was necessary to support the claim of preemption against county regulations relating to water quality, soil erosion, wildlife, vegetation, livestock, cultural and historic resources, geologic hazards, wildfire protection, recreation impacts, and permit duration.[246]

3. Board of County Commissioners of La Plata County v. COGCC

In a minor case decided between NARCO and BDS, International—La Plata County v. COGCC—La Plata County Commissioners brought action against the COGCC challenging the language of Rule 303(a), which stated that “[t]he permit-to-drill shall be binding with respect to any conflicting local governmental permit or land use approval process.”[247] The County argued that the rule “improperly expanded the operational conflict standard articulated in Bowen/Edwards by providing that [the Commission rule] prevailed whenever there is any conflicting local government permit or land use approval process.”[248] The court, applying Bowen/Edwards, Voss, and NARCO, determined that the COGCC had overstepped its authority.[249] “According to [the COGCC],” the court stated, “this rule is merely a statement of its understanding of relevant case law, in particular, Bowen/Edwards, and is not meant to contravene that law. COGCC’s understanding of relevant case law, however, is not binding upon us.”[250]

4. 2007 Amendments to the OGCA and 2008 COGCC Rule Making

The most recent major amendments to the OGCA were in 2007. House Bill 07-1341 increased the members of the COGCC from seven to nine, by including the directors of the Colorado Departments of Natural Resources and Public Health and the Environment as ex officio members. The bill reduced the number members who must have “substantial oil and gas experience” from five to three, and required that at least one member of the COGCC be a local government official, one have training in environmental or wildlife issues, one be experienced in soil conservation, and one be a royalty owner engaged in agriculture.[251] Inter alia, the amendments require the COGCC to consult with the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (“CDPHE”) to promulgate regulations to protect the health, safety, and welfare of the public, and ensure that the Department “has an opportunity to provide comments” during the decision-making process.[252] In addition, the Commission must “minimize adverse impacts to wildlife resources affected by oil and gas operations,”[253] consult with the Division of Wildlife when making decisions impacting wildlife, and implement best management practices and standards to conserve and minimize impacts on wildlife.[254]

The COGCC began implementing rule making on Dec. 11, 2008 “to protect public health, safety, and welfare, including the environment and wildlife resources, from the impacts resulting from the dramatic increase in oil and gas development in Colorado.”[255] The new regulations were developed with input from both the CDPHE and Colorado Parks and Wildlife. The regulations contained additional operating requirements in sensitive wildlife habitat and restricted surface occupancy areas.[256] However, many of the Rules’ substantive—but more importantly, procedural—requirements were left in place, including simple processes for industry to obtain rule variances and waivers, the limitations on procedural rights for neighbors and local governments, and extremely small penalties for violations.[257]

During the rule-making process, several counties and the Northwest Council of Colorado Council of Governments filed a motion with the COGCC to address their concerns that the Commission was acting beyond its powers and expanding the preemptive effect of its regulations.[258] They asked for clarification from the COGCC that the rules were to constitute a “floor” and not a “ceiling” in oil and gas regulation, and also asked that the COGCC acknowledge in its regulations that local governments have express authority to enact land-use, environmental, and surface impact aspects of oil and gas regulation more stringent than are imposed by the state.[259] This, they noted, is authorized by the Land Use Enabling Act, Colo. Rev. Stat. § 30-28-123 (2014), which provides that “[w]henever the regulations made under authority of this part . . . impose other higher standards than are required in or under any other statute, the provisions of the regulations made under authority of this part shall govern.”[260] They noted that the legislature had articulated, with express statements in each of the 1994 and 2007 amendments, its intent for local authorities to retain their land-use control while instructing the COGCC to be a better steward of both the environment and public health.[261]

The proposed solution of treating COGCC regulations as a “floor” rather than as an alternative to local rules seems particularly warranted in light two facts: first, the incredibly varied physical, economic, and political make-up of Colorado’s local communities; and second, the lack of institutional capacity by many local governments to defend lawsuits aimed at eliminating local rules. When the Bureau of Land Management decided to withdraw the parcels from the auction, [262] the Town of Paonia won a second reprieve that would have otherwise resulted in OGD within their small statutory municipality.[263] Had those leases gone through, Mayor Neal Schweiterman explained, the town staff of thirteen—including the sanitation department and police force—would not be easily capable of independently evaluating, implanting, and defending local regulations.[264] Defending regulations from industry lawsuits, in particular, threatens to be a costly burden for local communities.

D. Continuing Local Efforts to Regulate Oil and Gas Development

Since 1951, the oil and gas development industry has undergone profound changes. Easily accessed petroleum deposits have long since been drained. Now, unconventional sources—sources that are difficult to access or process into a commercial form—dominate the industry. Techniques such as horizontal or directional drilling,[265] slick-water, and multi-stage fracturing[266] have revolutionized the process and made it possible to recover hydrocarbons that until recently were uneconomical to produce. The number of active oil and gas wells in Colorado is currently over 50,000, more than double the number of wells that existed ten years ago. Although the rate of growth has slowed,[267] it could increase with new discoveries in the Denver-Julesburg Basin in the north Front Range.[268] This area is the most densely populated, fastest growing, and economically developed area of the state – it is also completely surrounded by a vast oil field that already contains half the wells in the state.[269] Suburban communities, outlying subdivisions, and even many municipalities now contain significant levels of OGD. The City of Greeley (pop. 96,000), whose ban was at issue in Voss, now has over 430 active OGD wells within city limits and over 1,220 including the immediate area projected for future city growth.[270]

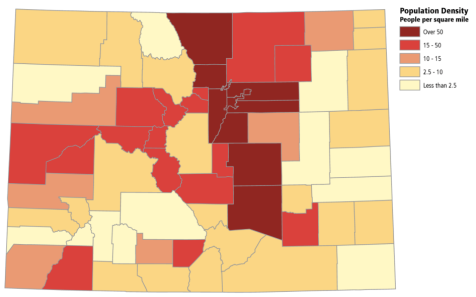

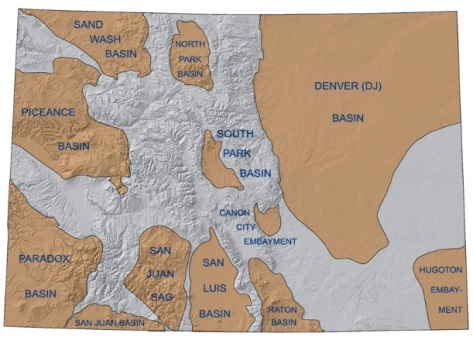

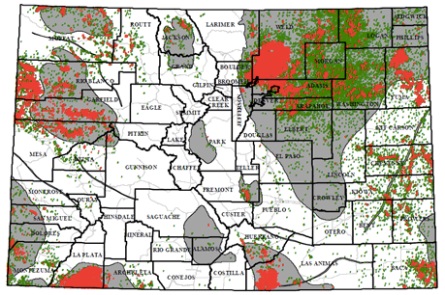

|

|

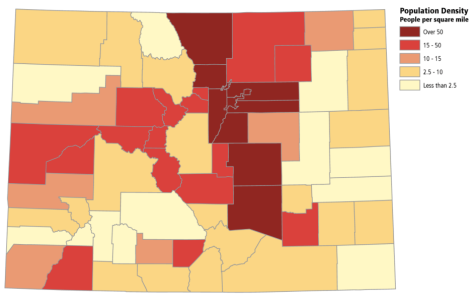

| Fig. 5, Colorado Oil and Gas Wells.[271] | Fig. 6, Colorado population density.[272] |

For many citizens, the industry has become controversial as the number of wells continues to grow in and around their communities.[273] Citizens are worried about the potential impacts, such as air, surface, and groundwater pollution,[274] surface disposal and evaporation of toxic drilling residues,[275] light and noise disturbances, and traffic.[276] The U.S. Geological Survey has identified waste disposal from fracking as the culprit in a large numbers of small earthquakes around the U.S.[277] There have been a number of fatal explosions, injuries, and evacuations, from both well sites and pipelines.[278] Surface owners have incurred economic losses from OGD, such as decreased property values, the cost of replacing well water with trucked-in water, and “reasonable” amounts of property damage.[279] A lack of transparency and the repeated denials of extensively documented harms have affected the social license to operate—the public support necessary for an activity or operator to proceed without social unrest—for OGD.[280] Citizens are skeptical about the willingness or ability of the state to protect their health and their air and water resources.[281] Industry has also undermined its social license with actions that seem to have little regard for the perception of local communities. For instance, the oil and gas industry has applied for permits to drill in playgrounds[282] and cemeteries,[283] and has brought aggressive and punitive litigation against homeowners and activists.[284]

The current dynamic is highly polarized; one side calls fracking “safe” and repeatedly asserts that groundwater contamination does not, has not, and cannot occur,[285] while the other side insists that the opposite is true. The current intensity of OGD activity, coupled with its proximity to large population centers, the public perception of under-regulation (warranted or not),[286] and a lack of trust in industry,[287] all combine to create a recipe for political activism. In 2012, local governments took up the fight again for the ability to protect their citizens and their communities.[288] In several cases, citizens used the ballot initiative process to overrule their local governments and demand an end, or at least a temporary reprieve, to drilling in their communities.[289] The movement started in Longmont before spreading to Boulder County, Fort Collins, and several smaller Front Range municipalities.

The home rule City of Longmont straddles Boulder and Weld County. Weld and Boulder County have drastically divergent views on OGD. Weld County has the highest number of oil and gas wells of any county in the nation with over 18,000,[290] while Boulder County has implemented a moratorium on new OGD through 2018.[291] In December 2011, Longmont imposed a moratorium on applications for oil and gas well permits while it considered enacting regulations to control the explosive growth of OGD in and around the city.[292] In February 2012, Longmont released a first draft of its new regulations.[293] The COGCC sent a letter stating that it believed some of the provisions were preempted.[294] The Commission believed that state law preempted portions of the ordinance, including the per se ban on surface oil and gas facilities within residential zoning districts and the claimed right to assess the “appropriateness” of certain practices and impose additional conditions on drilling and production.[295] In July 2012, after several months of discussions between the City, its local COGCC liaison, and the COGCC, the City Council approved the ordinance over the Commission’s objections. Longmont’s Ordinance O-2012-25 prohibits the city from issuing permits for oil and gas surface operations in residential zoning districts, requires public review for certain permit applications, bans open-pit disposal of mining waste, and limits waste disposal to industrial zoning districts. Additionally, it imposes other requirements on operators for siting and setbacks, operating, mitigating impacts, and the provision of financial sureties.[296]

Within a month, the COGCC filed a lawsuit against Longmont in Boulder County District Court, claiming that the 2008 COGCC rules expanded the preemptive effect of the Commission’s regulatory structure.[297] In its complaint for declaratory relief, the COGCC laid out eight claims against the city: (1) that state law preempted the City’s right to regulate the use of multi-well sites and directional drilling; (2) the proposed setback rules; (3) the wildlife habitat and species protection rules; (4) the ban on surface facilities and operations; (5) the chemical reporting rule; (6) the visual mitigation methods; (7) the water quality monitoring rule; and (8) the claim of authority to adjudicate operational conflicts.[298] In the fall of 2012, over eighty local government officials submitted a letter to the Governor of Colorado, asking the state to withdraw its lawsuit against the city of Longmont.[299]

While the state clearly viewed Longmont’s ordinance as a step too far, many residents felt the measure did not go far enough, given the plans of TOP Operating Company to drill near a city reservoir and popular recreation area, and in a local historic landmark ranch and community park.[300] In November 2013, the city’s voters approved Ballot Question 300 to completely ban hydraulic fracturing within the city.[301] In a grassroots campaign facilitated by Our Health, Our Future, Our Longmont, a local group, and Food & Water Watch, a national organization, proponents obtained 8,000 signatures in six weeks to put the measure on the November ballot.[302] Proponents had a budget of less than $24,000 in cash and in-kind donations, compared to the oil and gas industry’s $500,000. The ballot question still managed to win sixty percent of the vote.[303] Some observers believe that the “David and Goliath” image created by the massive financial imbalance in the campaign worked against the oil and gas industry.[304]

The Colorado Oil and Gas Association (“COGA”) filed a lawsuit against the city in Weld County District Court in December 2012, seeking to overturn the voter’s ban.[305] The suit alleged that state law preempted the ban, and that minerals worth $500 million would be taken if the ban were allowed to stand.[306] The state originally declined to sue Longmont over the ban, believing that Longmont lacked standing because it could not allege a particularized injury. However, the state filed an amicus brief in support of COGA,[307] and eventually joined the COGCC as a necessary party to the lawsuit.[308] Longmont successfully petitioned to change venue to Boulder County District Court since most of Longmont lies within Boulder County and Boulder County was the site of both the city charter and the disputed acts.[309] The court also granted TOP Operating’s motion to intervene, since it was operating in Longmont and would be directly affected by the outcome of the case.[310] The state’s lawsuit over the City Council’s regulations was stayed pending the outcome of the industry lawsuit over the voter ban.[311]

On July 24, 2014, the Boulder County District Court struck down the voter ban.[312] The judge stated:

The Court recognizes that some of the case law described above [primarily Voss and Bowen/Edwards] may have been developed at a time when public policy strongly favored the development of mineral resources. Longmont and the environmental groups, the Defendant-Intervenors, are essentially asking this Court to establish a public policy that favors protection from health, safety, and environmental risks over the development of mineral resources. Whether public policy should be changed in that manner is a question for the legislature or a different court. . . . . The conflict in this case is an irreconcilable conflict.[313]

The ruling was stayed, pending appeal.[314] Meanwhile, the case against the Longmont City Council’s regulations was dropped as part of a political compromise in which a statewide vote on local control was withheld from the November 2014 ballot.[315]

Despite its residents’ reputation for environmental activism and pro-regulatory zeal, Boulder County avoided the controversy of the early years of local OGD regulation by adopting carefully tailored regulations that did not impose a ban.[316] In 1993, Boulder County revised its Land Use Code to create a “Development Plan Review” process, requiring, among other things, financial sureties, emergency response plans, reclamation plans, a nuisance abatement plan, and mitigation for aesthetic, environmental, or wildlife impacts.[317] The Land Use Code also imposed criteria for evaluating Development Plans and conditions for approval.[318] Violators are subject to enforcement actions, including the loss of financial guarantees and the right of the Land Use Director to take corrective actions by entering the site.[319] Unlike other land uses, however, the Director can only approve or conditionally approve a Development Plan for oil and gas, with no authority to categorically deny a plan.[320] Boulder’s authority to enact these amendments was never challenged.

On February 2, 2012, the Boulder County Board of County Commissioners instituted a temporary moratorium on new OGD while the County evaluated its Comprehensive Plan and Land Use Code.[321] During the next eleven months, the Board held public meetings, solicited written comments and public testimony, and developed draft regulations for managing impacts from OGD.[322] The board adopted a resolution on December 20, 2012, approving various amendments to the County’s Land Use Code.[323] These amendments set up two processes by which oil and gas developers can pass through the Development Plan Review: a standard process which takes longer, or an expedited review process by which developers agree to a Memorandum of Understanding with more stringent requirements, including increased setbacks, air quality standards, water quality monitoring, and transportation standards and fees.[324] Boulder will require public engagement at every stage.[325] On January 24, 2013, the Board voted to extend the moratorium by an additional four months, in part to give it time to update the Land Use Code and integrate new COGCC setback and groundwater monitoring regulations.[326]

Fort Collins is a home-rule city located north of Denver, near the Wyoming border.[327] It has been ranked among the best places to live in the U.S. due to its “great schools, low crime, good jobs in a high-tech economy and a fantastic outdoor life.”[328] Currently OGD is limited to the Fort Collins field, in the northeast portion of the city, which has been in production since 1925.[329] On December 4, 2012, the Fort Collins city council approved a six-month moratorium (later extended to seven months) on new oil and gas permits, in order to review the city authority to regulate OGD, particularly groundwater monitoring and setbacks.[330] The council wanted particularly to investigate its authority to impose setbacks, prevent drilling in community parks and natural areas, and regulate the health and nuisance impacts from drilling.[331]

The Fort Collins City Council considered banning all oil and gas operations from the city, including hydraulic fracturing, which drew a sharp rebuke from the Governor, who threatened to sue the city.[332] Fort Collins estimates that approximately $200,000 dollars of annual revenue could be lost, although that number is uncertain since many revenue-producing wells would be allowed to remain under the new regulations.[333] On March 5, 2013, the city council of Fort Collins voted to ban hydraulic fracturing, amending its code to prohibit hydraulic fracturing for hydrocarbons, and to prevent the storage of drilling wastes and flowback in open pits.[334] The city agreed to exempt existing wells and pad sites, provided there was an agreement in place between the existing sites and the city to prevent methane release and to protect the public health, safety, and welfare.[335]

In November of 2013, local control measures were put up for a vote in four local jurisdictions: City of Boulder, Fort Collins, and Lafayette (all home rule cities), and the City and County of Broomfield. A measure in the City of Loveland was challenged in court before making it onto the ballot in the same election.[336] In Boulder, voters approved a five-year moratorium on oil and gas exploration, including in city-owned county open space.[337] Fort Collins voters approved a five-year moratorium on hydraulic fracturing and storage of oil and gas production waste, despite a resolution passed by the local city council opposing the measure. Lafayette voters decided that there would be no new oil and gas wells within the city. COGA filed suits against the resolutions in Fort Collins and Lafayette.[338] The trial court in both cases struck down the local provisions on state preemption grounds as set forth by Voss and Bowen/Edwards.[339] On June 10, 2014, the citizens of Lafayette filed a class action lawsuit against the State of Colorado, the Governor, and COGA.[340] The City of Lafayette argued that the Colorado Oil and Gas Act, as well as the industry’s enforcement of the act, violated the constitutional right of residents of the community to local self-government.[341]

In Broomfield, voters considered whether to impose a five-year prohibition on hydraulic fracturing.[342] On December 5, 2013, after a contentious and litigated election, the measure passed by a mere twenty votes.[343] A developer is currently challenging the moratorium, claiming that its preexisting Memorandum of Understanding with the municipal government should exempt its planned OGD activities from the time-out.[344] COGA has also filed a lawsuit challenging the prohibition.[345]

November 2014 was poised to be the setting of a historic election regarding the power of local governments. In early May it looked as if there could be as many as eleven measures addressing local control, setbacks, the “rights of nature,” regulatory takings, monetary disbursements to local governments, and other OGD related issues on the ballot.[346] Throughout the summer these were whittled down to four measures. Jared Polis, a Democratic Congressman from Colorado’s second congressional district (covering all of the areas that had voted to impose local controls on OGD except Longmont) backed two of these measures.[347] The other two measures were industry-funded.[348] Although early polling seemed to indicate a likely victory for the pro-local control measures,[349] political pressure from within the Democratic Party forced the sitting Congressman to withdraw them.[350] In a political compromise, both sides agreed to drop the remaining ballot measures, the state agreed to drop the first of the two legal challenges against Longmont, and the Governor agreed to initiate an eighteen-member “task force” to review Colorado’s oil and gas legislation and make suggestions to the legislature.[351] Some viewed the task force, however, as being heavily weighted with organizations and citizens friendly to development and to state control, and it did not include any of the organizations that have been involved with the local control issue.[352] Furthermore, a similar task force appointed by Governor Hickenlooper in 2012 to review state oil and gas regulations’ balance with local governments was widely considered a failure, with no perceptible impact on state regulatory or legislative enactments.[353]

In February 2012, Governor Hickenlooper established a task force to develop cooperative strategies for dealing with state and local conflicts over oil and gas issues.[354] The Governor charged the task force to develop mechanisms that avoid conflicting with local regulations while simultaneously “foster[ing] a climate that encourages responsible development.”[355] Two months later, the task force announced its recommendations. They focused on increasing communication between operators, local governments, and the public; increasing the delegation of the COGCC’s authority to inspect wells to local governments; and enhancing transparency within the COGCC with regard to Notices of Alleged Violations, self-reported incidents, and emergencies.[356] The task force was also charged with addressing issues such as setbacks, noise, operational methods, air quality, traffic, financial assurance and more; developing cooperative mechanisms; and suggesting potential legislative changes. The final recommendations, however, explicitly declined to suggest such changes and suggested only that impacts be addressed through COGCC rulemaking with a “robust stakeholder process.”[357] Although the task force was intended to be a collaborative effort to diffuse local concerns, it was widely criticized as over-representing state and industry interests, and in the end offered no real solutions.[358]

IV. THE BALANCING ACT: STATE RESPONSES TO PUBLIC CONCERN

The issue of which matters constitute ‘local concern’ versus matters of ‘statewide concern’ is one of tremendous importance to the question of state preemption.[359] The state interest in regulating development has typically been framed as both an interest in maximizing the production of natural resources within the state, and an interest in ‘uniformity’ of regulation at the state level so as to avoid a ‘patchwork’ of local regulations that might discourage industry.[360] However, it is inherently problematic in a democracy when the interests of the many impose on the rights of a few. Many voters expressing support for OGD activities and opposing local regulation are geographically removed from the negative impacts of those activities, although they may indirectly benefit economically.[361] The availability of public hearings and the rights of citizens to be involved in decisions regarding the issuance of drilling permits support the relevance of local regulations.[362]

Every major amendment to the OGCA since 1994 has included a legislative declaration that the rights of local governments are not to be abridged.[363] Where then does the battle arise? Why do local governments find themselves the victims of state intimidation, such that some believe they are powerless to do more to protect citizens than to conduct weed inspections at well pads?[364] Ironically, the COGCC and the state Attorney General have used the environmental mandates imposed by the recent OGCA amendments as a lever to broaden the conflicts that create state preemption.[365] Since the 1994 and the 2007 amendments to the OGCA, the COGCC seems to have considered itself essentially free to adopt any regulations, including those that create operational conflict preemption over local regulations, even if the state imposes a far lower standard for protecting local interests than a local government would otherwise allow.

A. Legislative and Executive Solutions

The current Governor of Colorado, John Hickenlooper, is a former petroleum geologist who strongly supports the oil and gas industry.[366] Hickenlooper appeared as a spokesperson for the Colorado Oil and Gas Association while in office,[367] and famously drank diluted fracking fluid to demonstrate its safety.[368] He has also appeared before the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources to argue against the disclosure of the chemicals used in fracking fluids.[369]