Abstract

This Article examines the resilience of New Mexico’s internal water management programs considering the interstate Colorado River obligations within the Law of the River. New Mexico’s annual apportionment of the Colorado River has been reduced in recent years, as aridification in the West continues. Much of the water delivered to New Mexico annually serves the San Juan Chama Project, which provides significant water for Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and Los Alamos. Given the strong likelihood of continued reductions in the near future, the state must consider the durability of existing water management strategies—the priority system, the Office of the State Engineer’s Active Water Resource Management program, the New Mexico Strategic Water Reserve, and individual acequia governance structures. Furthermore, the state should consider the consequences for reduced San Juan Chama Project deliveries for tribes within the state.

Table of Contents

Introduction 38

I. The Existing Law of the River is Ill-Suited to the Challenges of Climate Change 42

A. Prior Appropriation is a Critical Component of Water Management. 42

1. The System of Prior Appropriation governs water management across the West, including on the Colorado River. 42

2. New Mexico has a unique history of water management that has influenced how the state currently manages water. 43

B. The Colorado River Compact of 1922 and subsequent legislation established constraints for how the Colorado River may be used. 44

C. The Colorado River plays an integral role in New Mexico’s water supply. 46

1. The management of New Mexico’s Colorado River allocation is governed largely by geography. 46

2. To allow New Mexico to use its entire Colorado River allocation, further legislation was necessary. 48

3. The tribal portions of legislation were not completed on the same timescale as the nontribal portions and required significant concessions from tribes. 50

D. Water supplies in both the Colorado and Rio Grande Basins are shrinking as a result of anthropogenic climate change. 51

E. Both Federal and State responses to the continued reduction in water availability reflect the limitations of existing management frameworks. 53

1. New Mexico’s responses to the reduced water availability in both the Colorado and Rio Grande Basins have been effective but insufficient. 54

2. The Bureau of Reclamation has engaged in a variety of ineffective large-scale actions to mitigate the consequences of reduced water availability in the Colorado River. 56

F. New Mexico and the rest of the Upper Basin are unprepared for the growing risk of a Lower Basin Compact Call. 57

II. Shortages On The Colorado River May Pose A Serious Threat To San Juan-Chama Project Water Without A More Lenient Interpretation Of Existing Law, Nationally, Or The Implementation Of New Water Management Policy Within The State. 59

A. Existing law has created a complex framework for how shortages impacting New Mexico could be created and how they should be treated. 59

1. San Juan-Chama Authorizing language indicates that New Mexico will need to take reductions on SJCP water deliveries before Colorado and potentially the Lower Basin States. 59

2. The Priority System dictates how individual Colorado River Basin states, including New Mexico, should reduce their water usage to meet interstate compact obligations. 62

a. Prior appropriation governs both interstate and intrastate Colorado River water allocation and has the potential to create a cascade of serious reductions in water deliveries to junior users. 63

3. SJCP water is not governed under the prior appropriation system and is therefore managed outside of prior appropriation, however SJCP water reductions would likely necessitate calls on other water sources. 64

4. New Mexico does not enforce priority calls and therefore should not continue formally using the priority system. 65

5. It is not currently viable to use Active Water Resources Management administered by the OSE to mitigate the consequences of SJCP losses, but there may be opportunities in the future. 68

6. Acequias provide a model for water shortage sharing within communities. 69

7. New Mexico’s existing frameworks are robust, but the state should transition away from using a prior appropriation system and codify a more enforceable water management code that reflects the cultural values of the state. 72

Conclusion 73

On a February day, marked by a bluebird sky, the waters of the sediment-rich Rio Grande wind through the Middle Rio Grande valley. Without human intervention, the river would be in a base flow season, where the water is at one of the lowest levels during a water year.[3] In a heavily altered river system, like the Rio Grande, these historic low-flow seasons look very different—on this day in February, the river is running at 625 cubic feet per second, which is high for the late winter.[4] Much of this water has traveled from the headwaters of the Rio Grande in the San Juan Mountains of Southern Colorado.[5] Some of this water, however, is not native to the Rio Grande.[6] The San Juan-Chama Project (“SJCP”) supplements the Rio Grande with water from the San Juan River, using a series of conveyances and a reservoir.[7] In a typical year, 96,200 acre-feet (“AF”) of water is shunted annually from the San Juan into the Rio Grande, in accordance with the terms of the Colorado River Compact of 1922 and subsequent law, using the infrastructure built as a result of the Colorado River Storage Project Act.[8] The flows that are not transferred to the Rio Grande Basin from the San Juan rush down to the San Juan’s confluence with the Colorado River.[9] This water then rests in Lake Powell behind Glen Canyon Dam, where it waits to be released to meet Colorado River Compact obligations to states downstream of Lee Ferry.[10]

Within the last twenty years water levels at Lake Powell have declined so precipitously that water managers have begun to seriously analyze the risk that it may no longer be possible to meet the obligations set out in the Colorado River Compact.[11] Although there are myriad consequences of the anthropogenic water shortages on the Colorado River—that is shortages caused both by overuse and by reductions in water availability resulting from climate change—this Article focuses on how existing legal structures in New Mexico will respond to reduced SJCP water deliveries under a curtailment pursuant to Article III of the Colorado River Compact. Article III of the 1922 Colorado River Compact describes the delivery non-depletion requirement, which the Lower Basin states could hypothetically choose to enforce if the Upper Basin fails to make the agreed-upon deliveries.[12] In other words, Lower Basin states may require Upper Basin states to forbear use of their water allocation. In January of 2023, the Colorado River Board in California suggested that it may be time to do just this and enforce Article III.[13]

The 1948 Upper Colorado River Basin Compact (“UCRBC”), made between New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah, requires that shortages on the Colorado River be shared proportionally between these four Upper Basin States.[14] The limited framework for Upper Basin curtailments is found within the UCRBC.[15] It fails to dictate, however, how to implement this proportional shortage-sharing regime.[16] Furthermore, this regime does not consider the internal institutional consequences of shortages for individual states. Deliveries from the SJCP, which have been frequently constrained in the twenty-first century not by compact-driven rules but simply by bad hydrology, were just 65.5 percent of a full allocation in 2021,[17] and are likely to be further reduced in the coming years due to prolonged reductions in runoff and increased evaporation. In 2021, only 63,000 AF supplemented the Rio Grande due to water shortages in the Colorado River Basin.[18]

A curtailment, or reduction in the amount of water the Upper Basin may use, under Article III of the Colorado River compact will almost certainly lead to reductions in how much water New Mexico receives from the Colorado River via the SJCP. This would significantly reduce water available to municipalities like Albuquerque, Los Alamos, and Santa Fe, as well as agricultural areas like the Middle Rio Grande Conservation District (“MRGCD”). The state should contemplate the best way to apply shortage conditions, and municipalities should plan for water use restrictions and effective implementation of these use restrictions in advance of needing to implement them. While there is a concern that making (and more importantly, publishing) plans that reflect a prolonged water shortage could be leveraged by other states to demonstrate that New Mexico does not plan to make beneficial use of its full Colorado River allocation, this concern ignores the importance of water agencies planning for worst-case scenarios. This analysis will be useful to policymakers in identifying both areas where existing law can be used effectively and weaknesses in existing law that may require further development.

New Mexico has a unique history of water management regimes, beginning with the shared irrigation systems of the Ancestral Puebloans.[19] The principle of shared irrigation was applied by the Spanish when they managed acequias using the repartimiento philosophy.[20] It wasn’t until the early 1900s that New Mexico began following the system of prior appropriation, as part of the conditions for the Bureau of Reclamation (“Reclamation”) constructing and managing Elephant Butte Reservoir.[21] Though the priority system has been codified for over 110 years in New Mexico, priority calls have never been enforced in the state.[22] Given this multi-layered management framework, there is significant nuance in how current law in New Mexico governs climate change-related water shortages. This Article will analyze the efficacy of the existing legal structure in New Mexico in the face of significant reductions in SJCP water, in the event of a curtailment under Article III of the Colorado River Compact should the Upper Basin fail to meet its delivery obligations under the Law of the River. Such a curtailment has never happened before.[23]

The background explains the Law of the River, which includes the doctrine of prior appropriation, as well as the extensive body of federal law on the Colorado River. This Article explains the water management frameworks within New Mexico, which span the State’s unique application of prior appropriation, water right management through the Office of the State Engineer (“OSE”), and legal water structures specific to New Mexico, like acequias. This subsection also addresses New Mexico’s other internal water management frameworks. This Article then addresses the reduced water availability in both the Colorado River and Rio Grande River Basins and discusses the interplay between the two. Finally, the background section enumerates the federal and state responses to reduced Colorado River availability, culminating in the resulting risk for an Article III compact call.

In the analysis, this Article examines federal law, including interstate compacts and the SJCP authorizing statute to analyze the constraints on New Mexico water deliveries. This Article then looks at New Mexico’s existing water management systems to understand where New Mexico has robust water management systems and where the state has room to create a more resilient framework for water management in times of shortage. This Article first examines the application of prior appropriation in New Mexico, then it considers Active Water Resources Management and the law of acequias as alternative models that diverge from traditional prior appropriation. Using these analyses, this article explains that New Mexico already has a culturally robust water management system, and legal frameworks should be modified to more accurately reflect this system for easier implementation in times of shortage. The Article concludes with the observation that stationarity no longer exists, and thus the legal norms of the twentieth century in New Mexico will be ineffective in the face of coming water shortages.

I. The Existing Law of the River is Ill-Suited to the Challenges of Climate Change

The Colorado River is managed under a complex multi-level regime, involving federal, tribal, state, and municipal actors. Systems such as this are sometimes referred to as being “polycentric.” [24] This Section begins by explaining the doctrine of prior appropriation, the development of which influenced the creation of the Colorado River Compact of 1922. This article discusses the relevant interstate compacts, as well as the legislation appropriating funds to develop the infrastructure required to make use of the water allocated in the compacts. It addresses the current science on climate change-related water shortages in both the Colorado and the Rio Grande River Basins, and then details the federal and New Mexico state responses to the shortages. Finally, it explains New Mexico’s current risk for further Colorado River delivery reductions.

A. Prior Appropriation is a Critical Component of Water Management.

1. The System of Prior Appropriation governs water management across the West, including on the Colorado River.

The doctrine of prior appropriation, also referred to as “first in time, first in right,”[25] established a priority system that allocates water based on the seniority of water claims.[26] In years of shortage, those with the earliest priority dates could make a priority call and use the limited water before those with more junior claims.[27] These priority calls often result in curtailments. A curtailment to a water right involves a water administration entity reducing or completely stopping a water right holder’s access to their allocated water under the relevant governing law.[28]

Although Colorado, like many Western States, adopted the doctrine of prior appropriation in the late 1800s to manage water usage rights,[29] prior appropriation was not adopted in New Mexico until 1907.[30] It was implemented specifically to allow Reclamation to invest in large-scale water storage projects, such as the Carlsbad Irrigation District and Elephant Butte Reservoir.[31] Historically, prior appropriation was first applied in courts before it was official adopted into state statutes, and in some cases into state constitutions.[32] In New Mexico, the addition of prior appropriation to the state constitution ran directly counter to the existing water-sharing system in the state and was done primarily at the behest of Reclamation.[33] While the official adoption of prior appropriation allowed Reclamation to develop large scale water storage programs in New Mexico,[34] primarily for the benefit of agricultural irrigation and the resultant economic development, it did not change the existing water allocation norms in the state, which focused largely on sharing shortages rather than the more Anglocentric philosophy of cutting off water to more junior users in the event of a shortage.[35] This trend continues to influence how the New Mexico State Engineer manages water in the state.

2. New Mexico has a unique history of water management that has influenced how the state currently manages water.

Tribal water entitlements and New Mexico’s historical water-sharing doctrines make enforcement under a pure prior appropriation regime difficult. Queen Isabella of Spain first acknowledged Pueblo water rights during Spain’s occupation of the land that is now New Mexico.[36] Spain consistently recognized the Pueblos’ right to use water in the Middle Rio Grande under the doctrine of Repartimiento de Agua.[37] This system required all parties in the water system to share the burden of water shortages and did not consider priority dates.[38] Mexico recognized tribal water rights as repartimiento continued and were eventually recognized by the United States government, after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.[39] This lasted until 1907 when the doctrine of prior appropriation was introduced to New Mexico.[40] In 1908, the Supreme Court in Winters v. United States acknowledged the seniority of tribes’ water rights, but many of those rights across the United States, including in New Mexico, were never quantified, which makes it difficult for tribes to enforce their water rights.[41] Tribal water rights are an essential part of New Mexico’s water allocations, and tribal considerations are a necessary component of any water allocation conversation.

B. The Colorado River Compact of 1922 and subsequent legislation established constraints for how the Colorado River may be used.

In 1922 representatives from the seven Colorado River Basin states—Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California—met in Santa Fe, New Mexico to sign the Colorado River Compact (“Compact”).[42] The Compact was subsequently ratified by Congress, codifying it as the first interstate compact governing the allocation of the Colorado River.[43] The Compact allocated 7.5 million acre-feet (“MAF”) of water to Upper Basin states (Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico) and 7.5 MAF to Lower Basin states (Arizona, Nevada, and California).[44] In the years leading up to 1922, the Colorado River experienced the wettest period in 500 years,[45] and the fifteen MAF of water allocated by the compact appeared to be merely a portion of the water available annually.[46] The representative from New Mexico reported that there were “many million acre-feet” of Colorado River that were “unappropriated and unused.”[47] This representative, S.B. Davis Jr., continued to indicate that there were three MAF from the San Juan River that could be used for agriculture, and noted that water from the San Juan River was potentially New Mexico’s most valuable resource.[48]

In the decades following the 1922 Compact, states saw significantly less water in the Colorado River than had been recorded in the years leading up to the creation of the Compact; much less water than S.B. Davis Jr. had reported. Generally, a compact call involves one state filing a legal claim demanding that another state forbear the use of all or part of its water allocation so that the claimant state may receive its full water allocation under an interstate compact.[49] While there were no compact calls made, owing to the bounty of water stored in Lake Mead (and later Lake Powell), the circumstances under which a compact call would arise became a topic of conversation. In the case of the Colorado River Compact, a compact call would involve a Lower Basin state or states calling upon Upper Basin states to reduce their water use to meet the terms of the Compact.

While the Colorado River water had been divided between basins, the Upper Basin and the Lower Basin still needed to allocate portions of water internally. The Upper Colorado River Basin Compact (“UCRBC”) was ratified in 1949.[50] The Upper Basin allocated water via percentages, which would turn out to be a prescient decision in light of current water shortages, where a percentage allocation is reduced proportionally.[51] Under the UCRBC, New Mexico’s Colorado River entitlement is 11.25 percent of the Upper Basin’s Colorado River allocation.[52] Although New Mexico was legally entitled to roughly 843,750 AF,[53] the state would need to divert 96,000 AF of the entitlement away from the lands adjacent to the San Juan River and out of the Colorado River Basin to be used in other parts of the state. The remaining 747,750 AF of water were to remain in the Colorado River basin in New Mexico to supply water for the agricultural needs of the San Juan Valley, the Navajo Nation, and the Jicarilla Apache Nation.[54] Much of this in-basin water entitlement was never developed.[55] The 96,000 AF of water that was destined for use out of the basin, however, was needed for further development along the Rio Grande. It was not for another twenty-two years, in 1962, that New Mexico would see legislation to create the necessary infrastructure to use its entire allocation.[56]

C. The Colorado River plays an integral role in New Mexico’s water supply.

1. The management of New Mexico’s Colorado River allocation is governed largely by geography.

The section of river that most people consider the Colorado River runs from Colorado to Utah, to Arizona, bypassing New Mexico entirely.[57] However, the Colorado River system consists of three major tributaries that join in Utah, just upstream from Glen Canyon.[58] The northernmost fork, the Green River, begins in Wyoming.[59] The middle fork, which was once called the Grand, but is now known as the Colorado River, begins in the northern Rockies of Colorado.[60] The San Juan River, however, makes its headwaters in the San Juan Mountains, just north of the Colorado-New Mexico border, and collects in Navajo Lake before it is released to run south through Bloomfield, New Mexico.[61] The river continues through Farmington, where it joins the Animas River.[62] The San Juan River then flows to Shiprock and traverses much of the Navajo Nation as it winds back northward to its confluence with the Colorado River in Utah, just east of Lake Powell.[63]

On the eastern side of the Continental Divide, the Rio Chama also begins in the San Juans in Southern Colorado, further east than the San Juan, quite close to the Jicarilla Apache Nation.[64] It travels south, directly through the town of Chama.[65] Downstream of Chama, the Rio Chama is joined by Willow Creek, where imported San Juan-Chama water is stored in Heron Reservoir.[66] Just downstream from the confluence of Willow Creek and the Rio Chama, the river enters by El Vado Reservoir.[67] It continues further south to Abiquiu Lake northwest of Abiquiu, where it turns eastward.[68] On the Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo, the Rio Chama joins the Rio Grande.[69] Since the Colorado River does not physically run through the state, New Mexico would need to rely on the San Juan River, a tributary of the Colorado, to deliver the allocation.[70] Even this solution, however, would require the development of infrastructure to store and transport the water.[71] This motivated the creation of the Colorado River Storage Project Act (“CRSPA”).[72]

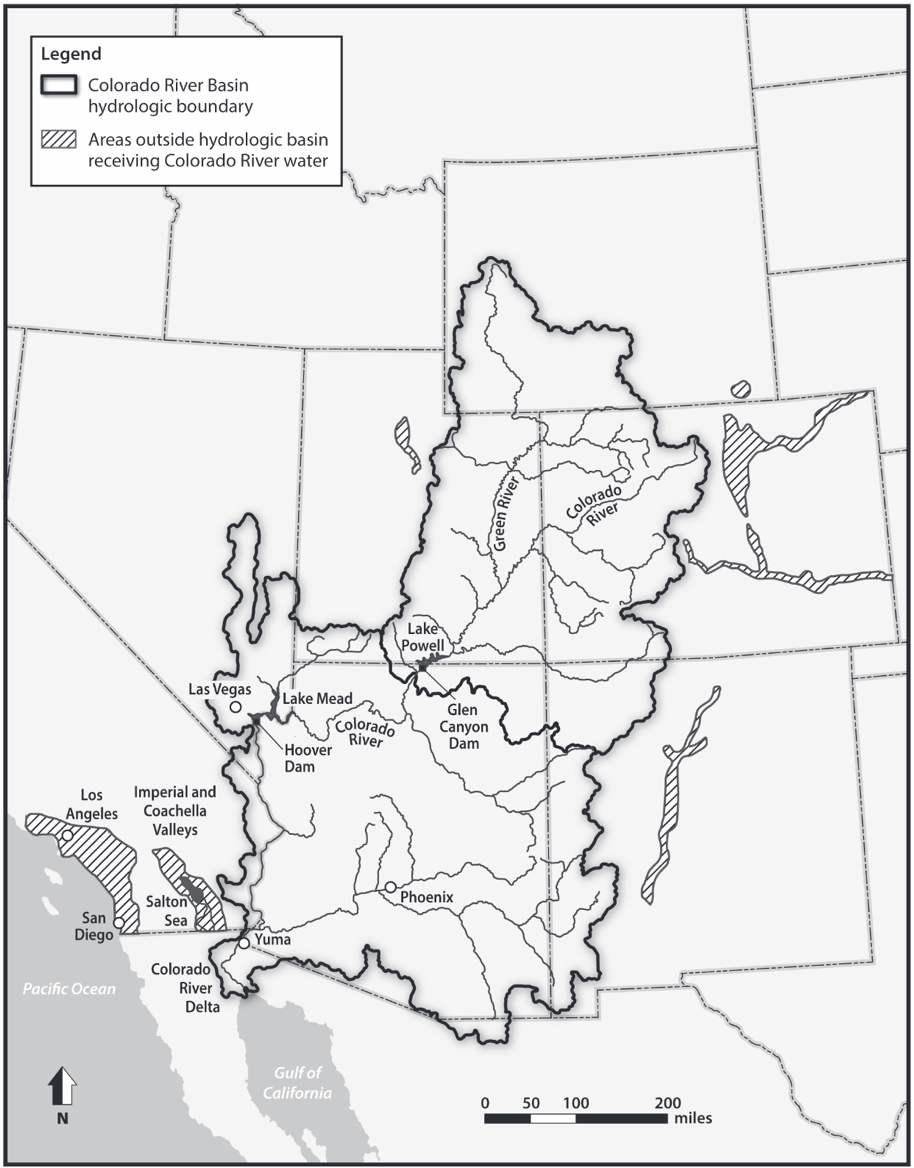

Figure 1: Eric Kuhn & John Fleck, Science Be Dammed 10 (2019). Map used with permission.

2. To allow New Mexico to use its entire Colorado River allocation, further legislation was necessary.

Although allocating the Colorado River seemed like the perfect solution to equitably distribute water within the basin to support the developing urban and agricultural hubs of the West, it was done before infrastructure existed to get the water from the river to the people who wanted to use it. The CRSPA authorized federal funding to designated Colorado River storage projects and infrastructure in the Upper Basin, including reservoirs.[73] When these projects were first introduced, even with comparatively rudimentary hydrological measurements, there were concerns about the cost of evaporative losses.[74] These concerns extended to losses from conveyance systems like those used in the SJCP.[75] The SJCP was authorized by Congress in 1962 to deliver water from tributaries of the San Juan, part of the Colorado River system, to the Chama River, part of the Rio Grande River system.[76] The idea for the SJCP dates to the 1930s, when the National Resources Planning Board suggested it as a solution to chronic water shortfalls on the Rio Grande. The idea was to move a share of New Mexico’s Colorado River Basin water via transmountain diversion across the Continental Divide to the heavily populated Rio Grande Valley for use in Albuquerque and other communities.[77] New Mexico’s approval of the Rio Grande Compact in 1938 was predicated in part on the availability of SJCP water to supplement the natural flow of the Rio Grande in support of the growing city of Albuquerque and other central New Mexico water users.[78] The project was authorized by Congress in 1962, with the first water deliveries made in 1971.[79]

The SJCP created a series of tunnels that divert flows from the Navajo, Little Navajo, and Rio Blanco Rivers.[80] This water is transferred to the Rio Grande basin, where, when New Mexico receives the full allocation of SJCP water, it provides 22,000 AF of water for irrigation and 74,000 AF for municipal use in Santa Fe, Los Alamos, and Bernalillo County. The SJCP water has become a critical part of water supplies, particularly in the Middle Rio Grande (“MRG”), which includes both agriculture and Bernalillo County municipalities.[81] Congressional appropriations for the SJCP provided funding for the development of the SJCP conveyance to the Rio Grande, as well as funding for the Navajo Nation to develop its water infrastructure.[82] The language in the appropriations prioritized the Navajo Irrigation Project, however the SJCP was constructed first.

3. The tribal portions of legislation were not completed on the same timescale as the nontribal portions and required significant concessions from tribes.

It took ten years for the non-tribal portions of the SJCP to be completed.[83] New Mexico received 100 percent of its UCRBC allocation in 1972.[84] The tribal portions of the project took even longer. Paradoxically, New Mexico advocated for a larger portion of Colorado River water during the negotiations of the UCRBC to supply the water owed to tribes under the Winters doctrine.[85] In the following years, a settlement with the Navajo Nation determined that the Nation has a right to 405,950 AF of Colorado River water in New Mexico.[86] One of the conditions of this settlement was the changing of the Navajo Nation priority date from 1868, the date of reservation establishment, to two dates: 1955 and 1968.[87]

Jicarilla Apache Nation has a very different story. Jicarilla Apache Nation is recognized to have 32,000 AF of water in New Mexico, under the terms of its 1992 settlement.[88] Unlike the Navajo Nation, the Jicarilla Apache Nation has significantly less farmable land.[89] For this reason, Jicarilla Apache Nation previously leased its water allocation for power plant cooling at San Juan Generating Station.[90] When the generating station closed, the allocation was converted to “system water” and now flows to Lake Powell.[91] Some experts consider this system of water to be an asset in the Upper Colorado River Basin Demand Management.[92] In an agreement reached between Jicarilla Apache Nation, the Nature Conservancy, and the State of New Mexico, the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission signed a ten-year lease in which the state will pay Jicarilla Apache for 20,000 AF of water annually.[93] The funds for this lease are from New Mexico’s Strategic Water Fund.[94]

The Pueblos of the Middle Rio Grande (Cochiti, Santo Domingo, San Felipe, Santa Ana, Sandia, and Isleta),[95] along with the Rio Grande and Rio Chama Pueblos to the north (Taos, Ohkay Owingeh, Santa Clara, and San Ildefonso) rely on water from the Rio Grande.[96] All Pueblos south of Taos also rely on the water that flows from the Rio Chama/Rio Grande confluence. Although the tribal component of New Mexico’s Colorado River allocation has historically been downplayed, it will become more and more critical in light of reduced Colorado River water availability.

D. Water supplies in both the Colorado and Rio Grande Basins are shrinking as a result of anthropogenic climate change.

Anthropogenic climate change has fundamentally altered the hydrology of the West. Snowpack in the Never Summer Range of Northern Colorado, where the Colorado River begins, is evaporating before it can melt and reach the Colorado River.[97] This leads to a lack of runoff, which significantly reduces Colorado River flows.[98] The aridification of the twenty-first century has persisted in the Colorado River and Rio Grande Basins, and as annual temperatures continue to rise, Reclamation warned in December 2022 of a risk that the Colorado River releases at Lee Ferry would be reduced to around seven MAF, for at least two years.[99] These estimates show evaporative losses at Lake Powell around 200,000 AF a year.[100] Independent analyses, however, show that the 24-month Projections released by Reclamation tend to be inaccurate predictors that do not account for increasing aridification of the Southwest.[101] Aridification, broadly, is the gradual change of a climate from wet to dry.[102] Though some of this aridification is the result of climate trends independent of anthropogenic climate change, warming temperatures in the Colorado River Basin are the result of greenhouse gas emissions.[103] General warming in the Colorado River Basin will continue unless global greenhouse gas emissions are significantly reduced.[104] The warmer, drier climate is the result of the combined effects of regular climate variability and anthropogenic climate change.[105] While the shift from the wetter, cooler climate of the Southwest, observed in the 1980s and 1990s, towards the hotter, drier climate observed today can be mostly attributed to internal atmospheric circulation variability, the warming trend in the Southwest is also the result of human climate interventions.[106] New Mexico’s temperature rose two degrees Fahrenheit from 1970 to 2020, and is projected to continue to rise.[107] Surface water flows and groundwater recharge are projected to decline by twenty-five percent over the next half-century.[108] This essentially means that these conditions are no longer drought conditions but rather an aridification trend.

Global warming is characterized by an increase in annual ambient temperatures, also typical of a drought, which in turn increases water temperatures and further reduces precipitation.[109] Similarly, the Rio Grande through Albuquerque ran dry in 2022 for the first time in four decades.[110] Elephant Butte Reservoir dropped to three percent of its total capacity by September of 2021.[111] Current estimates show that Rio Grande flows will be reduced by between four and fourteen percent by 2030 and between eight to twenty-nine percent by 2080.[112] The Rio Grande Basin will continue to deal with climate change related flow reductions beginning in the San Juan mountains, so water availability in both basins will be universally reduced.[113] A heavy snowpack in the winter of 2022–2023 temporarily reduced the need for seven MAF releases at Lee Ferry, but multiple analyses project that Colorado River flows will be reduced as a result of both increased evaporation and reduced snowpack.[114]

E. Both Federal and State responses to the continued reduction in water availability reflect the limitations of existing management frameworks.

1. New Mexico’s responses to the reduced water availability in both the Colorado and Rio Grande Basins have been effective but insufficient.

New Mexico has implemented a variety of internal approaches for dealing with water shortages. The OSE manages water rights and allocation using the AWRM initiative, which outlines rules for metering water, local water management by Water Masters within communities, and explicitly developing rules for shortage sharing.[115] This program was first implemented in 2004 as an alternative to priority calls, which the OSE recognized would be impossible to implement at the time.[116] OSE uses AWRM to manage six unique water basins, called “priority stream systems” which include the Rio Chama basin,[117] but notably does not include the MRG basin because of the MRG’s unique management under the MRGCD.[118]

New Mexico also created a Strategic Water Reserve for purposes such as complying with interstate water compacts, like the Compact and the UCRBC.[119] The Strategic Water Reserve is implemented and administered by New Mexico’s Interstate Stream Commission.[120] New Mexico invests in the Strategic Water Reserve fund, which allows the state to buy water rights to use as system water, like that from the San Juan Generating Station, which is kept in-stream to be delivered to Lake Powell.[121] In 2020, the state legislature of New Mexico appropriated $750,000 to meet UCRBC obligations.[122] More recently, funds from the Strategic Water Reserve were used to secure the ten-year lease on Jicarilla Apache’s Colorado River water rights.[123] In 2023, the Strategic Water Reserve received a $7.5 million appropriation in the New Mexico House Budget Bill, and another $150,000 in the supplemental appropriations bill.[124] This funding will be used to focus efforts on the priority groundwater basins established in 2022, which includes the MRG,[125] meeting Endangered Species Act requirements across the state, including in the MRG,[126] and meeting compact obligations.[127]

On a local level, municipalities such as Albuquerque have developed extensive plans for mitigating the effects of water shortages. Municipal water authorities, such as the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority (“ABCWUA”) must obtain water rights and then distribute water to domestic users who do not hold the rights in exchange for payment.[128] The Water 2120 Report, sponsored by the ABCWUA, considers water management strategies to ensure water security for Albuquerque and Bernalillo County for the next ninety-eight years.[129] The report notes how critical the use of Rio Grande surface water is for the replenishment of the Albuquerque Aquifer.[130] The report also notes that under the worst-case scenario for water availability, there exists only enough water for the population of Bernalillo County for another forty years.[131] These types of reports further underline the need for more comprehensive water management across the state.

Much of the water in the MRG that is not distributed within the ABCWUA network is managed by the MRGCD. MRGCD has implemented a Water Bank to manage internal aridification stressors. The MRGCD Water Bank was established in 1995 with the goal of protecting water rights of the district itself and landowners within the district, promoting “the beneficial use of water for agriculture,” and supporting water supplies and aquifer recharge.[132] The Water Bank applies to lease water that is not currently being put to beneficial use, but was used historically.[133] Leases are renewed annually, under a December 2009 amendment to the Rule.[134]

2. The Bureau of Reclamation has engaged in a variety of ineffective large-scale actions to mitigate the consequences of reduced water availability in the Colorado River.

Reclamation has attempted to mitigate the consequences of continued low flows into Lake Powell since 2007.[135] The 2007 Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and the Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead were issued to address the impacts of aridification on the Colorado River Basin reservoir operations.[136] These guidelines established operational guidelines that reduce releases from Lakes Powell and Mead under certain conditions and attempted to create incentives for Basin states to reduce their water usage voluntarily.[137] Twelve years later, in 2019, Reclamation and Upper Basin states executed the Drought Response Operations Agreement, which dictated a change in water releases to maintain certain levels at Lakes Powell and Mead.[138] It also established the Drought Contingency Plan program, which required that states develop their own plans for managing water amidst aridification.[139] The language of the plan itself, though, indicates its shortsightedness—it is intended to manage drought, a brief period of dryness, rather than respond to the ongoing aridification of the West.

Recently, Reclamation issued the 2022 Drought Response Operations Plan (“DROP”) to govern Upper Basin state actions to respond to reduced flows on the Colorado River.[140] The DROP was in effect for seven months before water levels in Lake Powell dropped so precipitously that an amendment to the DROP was necessary.[141]

These steps proved insufficient, forcing the Department of the Interior, amid a drumbeat of stark news coverage with pictures of wrecked speedboats emerging from a shrinking Lake Mead,[142] to formally acknowledge in August 2022 that it lacked the legal tools necessary to manage the crisis.[143] “Given that water levels continue to decline, additional action is needed to protect the System,” the Department noted in a Federal Register Notice.[144]

This has cascading impacts. The existing Compact, the UCRBC, and water management within New Mexico are insufficient to deal with the continued water shortages, as evidenced by the seemingly endless parade of amendments to legislation, new drought mitigation plans, and new deadlines for establishing new stopgap measures.

F. New Mexico and the rest of the Upper Basin are unprepared for the growing risk of a Lower Basin Compact Call.

The first five months of 2023 saw a welter of proposals and counter-proposals in response to the Interior Department’s call for suggested approaches to Colorado River Basin water supply shortfalls. On January 31, 2023, six Colorado River Basin states—Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Arizona, and Nevada—submitted a proposal to Interior to share Colorado River usage reductions in light of continuing aridification.[145] This proposed shortage sharing is referred to as the “Consensus-Based Modelling Alternative,” which would effectively modify the prior appropriation system for users on the Colorado River to share a significant portion of shortages in a system more akin to repartimiento.[146] California offered an alternative proposal. In a letter written the day after the six-state letter, California explained that the state would prefer that shortage conditions be enforced through priority calls.[147]

Then in a compromise, the three Lower Basin states—California, Nevada, and Arizona—offered yet another proposal, attempting to sidestep the need for any federal action by offering up voluntary, compensated water use reductions between 2023 and 2026.[148]

Under the prior appropriation system, California receives water before Arizona.[149] Furthermore, there is significant concern that the solution proposed by California would also hold Upper Basin states accountable for climate change-related reductions in Colorado River water deliveries at Lee Ferry.[150] New Mexico expressed concerns about being held jointly responsible with the Upper Basin states for a hypothetical in which the agreed-upon amount of water is not delivered to Lower Basin states because of hydrological shortages.[151] California’s letter indicated an intent to act in the precise way New Mexico feared.[152] In the event of an Article III curtailment resulting from a Compact call, what are the consequences for New Mexico?

The Middle Rio Grande relies heavily on SJCP water from the Colorado River. There is legal uncertainty, however, around the future of SJCP deliveries in light of the prolonged water shortage on the Colorado River. As water supplies continues to shrink, there is a possibility that New Mexico will be forced to take significant cuts to their SJCP water allocation. The following analysis investigates what these cuts could look like and examines New Mexico’s existing water management framework to understand how to mitigate the hardship of these potential cuts.

II. Shortages On The Colorado River May Pose A Serious Threat To San Juan-Chama Project Water Without A More Lenient Interpretation Of Existing Law, Nationally, Or The Implementation Of New Water Management Policy Within The State.

A. Existing law has created a complex framework for how shortages impacting New Mexico could be created and how they should be treated.

1. San Juan-Chama Authorizing language indicates that New Mexico will need to take reductions on SJCP water deliveries before Colorado and potentially the Lower Basin States.

In 1962, Congress passed an Act authorizing the construction of the Navajo Indian Irrigation Project and the beginning stages of the SJCP.[153] The Act states that:

[T]he Secretary shall operate the project so that there shall be no injury, impairment, or depletion of existing or future beneficial uses of water within the State of Colorado, the use of which is within the apportionment made to the State of Colorado by article III of the Upper Colorado River Basin compact, as provided by article IX of the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact and Article IX of the Rio Grande compact.[154]

This passage references two sections of the UCRBC. Article III of the UCRBC establishes percentages of the annual Colorado River flow allocated to each Upper Basin State.[155] New Mexico, as noted earlier, is entitled to 11.25 percent of the Upper Colorado River Basin Colorado River allocation.[156] Colorado, in contrast, receives 51.75 percent.[157] Although the Upper Basin states are subject to significant Colorado River curtailment within the Upper Basin should they exceed their UCRBC percentage allocation, sometimes referred to as the “penalty box,”[158] New Mexico may be forced into curtailments before exceeding their full 11.25 percent allocation. This Act is worded such that New Mexico is not only prohibited from exceeding its 11.25 percent cap on Colorado River water usage, but New Mexico may also be required to curtail its SJCP water usage if the SJCP water diversions interfere with Colorado receiving its full 51.75 percent of the Upper Colorado River allocation. This language is significant because it permits Colorado to require New Mexico to reduce its SJCP water use if Colorado determines that the SJCP diversions are impeding Colorado’s ability to make full use of its Colorado River water.

This clause, as it is written in the 1962 SJCP authorizing statute, has never been enforced for two primary reasons. First, releases of SJCP water from Heron Dam are managed by Reclamation, and these releases of SJCP water scale are based on the amount of water in the reservoir.[159] San Juan-Chama Contractors, the groups that receive SJCP water, are entitled to their allocation when the water is released from Heron Dam.[160] Reclamation calculates how much water is released annually; however, it appears that this decision is made without input from New Mexico.[161] This means that New Mexico never receives more SJCP water than is available. The second consideration is that Colorado has never used its entire Colorado River allocation.[162] Consequently, Colorado has never been determined to require forbearance from New Mexico when Colorado has a little over a million acre-feet of undeveloped Colorado River entitlements.[163] In the coming years, however, this status quo could change.

New Mexico is not only beholden to Colorado for its water allocation—the Act also indicates that all SJCP water is subject to a non-depletion agreement under the Colorado River Compact. The Act reads:

The diversion of water for either or both of the projects authorized in this Act shall in no way impair or diminish the obligation of the ‘States of the upper division’ as provided in article III(d) of the Colorado River compact ‘not to cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of seventy-five million acre-feet for any period of ten consecutive years reckoned in continuing progressive series beginning with the first day of October next succeeding the ratification of this compact.’[164]

The wording here is clear—SJCP water is legally bound to Article III’s provision regarding the delivery of 7.5 MAF of water to Lower Basin states at Lee Ferry. Though the 1922 Compact did contain a non-depletion provision, it is not clear whether this provision was intended to be a delivery obligation or a usage restriction.[165] Said differently, the language of the Compact indicates that Upper Basin states must not deplete the flow, but the Compact is silent on the issue of external factors, such as climate change, causing a flow depletion. It is possible to interpret the 1922 Compact, independently of other law, to mean that the Upper Basin states are not responsible for reducing their water usage to accommodate external factors like climate change. However, language such as that found in the SJCP authorizing statute take the much less generous interpretation of the 1922 Compact and instead hold the Upper Basin states accountable for reducing their water usage as much as is necessary to deliver 7.5 MAF to the Lower Basin.[166] The SJCP authorizing statute’s interpretation of Article III in the 1922 Compact is consequential for New Mexico in the face of current Colorado River disputes.

As California threatens legal action to enforce their Colorado River rights, Upper Basin states, particularly Colorado, are feeling the squeeze. Colorado has not made full use of its entitlement, and it will likely be unable to do so under current aridification conditions. Due to the 1922 Compact requirements, under Article III, there is debate on whether Colorado may be required to reduce its Colorado River water usage significantly to ensure that the Lower Basin states receive their 7.5 MAF of Colorado River water. As Colorado faces a future in which it must use less and less water, the state may call on New Mexico to use less SJCP water with the goal of shoring up Colorado’s own water supply. If Colorado determines that New Mexico’s usage of SJCP water is infringing on Colorado’s water supply, further limited by an Article III curtailment, Colorado could use the SJCP authorizing language to require New Mexico to reduce its SJCP water usage.

Enforcement of this forbearance would likely be implemented by Reclamation, which controls releases from Heron Dam.[167] Under this regime, it is unclear whether SJCP water would still be shunted to Heron Dam from the San Juan, or whether the diversions would be closed and water would remain in the San Juan. While legal action is possible, given New Mexico and Colorado’s relationship, it seems more likely that this agreement would be established internally. New Mexico should prepare for these conversations with Colorado and Reclamation now and develop a plan of action to avoid a forced reduction in SJCP water deliveries. New Mexico should also consider the durability of its existing mechanisms for managing water shortages.

2. The Priority System dictates how individual Colorado River Basin states, including New Mexico, should reduce their water usage to meet interstate compact obligations.

This section envisions the consequences of applying prior appropriation principles to continuing water shortages. In light of the shortcomings of prior appropriation, as well as the limitations of the system within New Mexico, we determine that this legal tool is insufficient to meet the future needs of the state.

a. Prior appropriation governs both interstate and intrastate Colorado River water allocation and has the potential to create a cascade of serious reductions in water deliveries to junior users.

The system of prior appropriation is embedded into the Law of the River. Article VIII of the 1922 Compact protects all pre-compact rights.[168] That means that any water rights holders with priority dates from before 1922 have a legal entitlement to their water over any rights determined by the 1922 Compact. Within each Colorado River Basin state, reducing Colorado River water usage could ostensibly be accomplished by allowing the water management authority in each state to make priority calls and curtail the most junior users of Colorado River water. In New Mexico, this is the Office of the State Engineer.[169] This curtailment would require Upper Basin states, like New Mexico and Colorado, to implement internal Colorado River cuts with the consequence of leaving more water instream, allowing that water to flow to Lake Powell. Lower Basin states would need to implement similar priority cuts with the goal of leaving water in Lake Mead. Each state would need to develop their own system for implementing these priority calls. Some states, such as Colorado, have existing structures for enforcing priority calls. Other states, like New Mexico, do not officially enforce priority calls.[170] When the Upper Basin agreed to the 1922 Compact, they agreed to take on the drought risk. They did not, however, agree to take on ongoing worsening aridification risk. For this reason, some have argued that in light of climate change considerations, a compact call is irrelevant.[171]

The Priority System also impacts how water is delivered to Lower Basin states in times of shortage. In Arizona v. California, the Court recognized many users in California were granted earlier priority dates to the Colorado River than users in Arizona.[172] In other words, in a management framework that relies exclusively on the Priority System, Arizona Colorado River water users will broadly have to take cuts before California does, based on a priority table created in Arizona v. California. This raises some ethical concerns that this paper does not cover,[173] and it also has further-reaching consequences.

The Priority System, if implemented on the Colorado River as California advocates,[174] would likely force Upper Basin states, including New Mexico, to use their State Engineer to make calls on some junior users in order to meet what has been treated as a non-depletion stipulation in the Colorado River Compact.[175] If California demands that Reclamation enforce California water users’ priority to the Colorado River against Arizona users, Arizona will, out of necessity, make a call against Upper Basin states to deliver the full allocation downstream. In their December 2022 letters, Arizona explicitly asked that releases from Lake Powell do not drop below a certain mark, so Arizona is already aware of and trying to guard against this risk.[176] In contrast, New Mexico has no internal system for enforcing priority calls.[177] This cascade of priority calls creates an Article III curtailment in all but name. This result is absurd.[178]

3. SJCP water is not governed under the prior appropriation system and is therefore managed outside of prior appropriation, however SJCP water reductions would likely necessitate calls on other water sources.

When allocations for the SJCP were drafted in the SJCP Authorizing Statute of 1962, the creators were beginning to understand the potential for water shortages in the Rio Grande and Colorado River Basins.[179] For this reason, SJCP delivery reductions are implemented proportionally between all users.[180] Rather than using the priority system for allocation, SJCP was allocated statutorily.[181] Consequently, there will never be a priority call for SJCP water because the SJCP allocations exist outside of the prior appropriation system. Instead, priority calls are possible for users whose SJCP allocation has been reduced so much that the water users’ other water rights are insufficient to meet their needs. A loss of SJCP water would create a cascade of water shortages, since users would be drawing more completely on other sources, which would create water stress on allocated water that originates in the Rio Grande Basin. Although SJCP water cannot be called, it is necessary to understand how SJCP shortages could cause internal priority calls.

4. New Mexico does not enforce priority calls and therefore should not continue formally using the priority system.

The State Engineer is responsible for issuing and overseeing priority calls.[182] Although some users have asked OSE to make priority calls, the State Engineer has never enforced a priority call in New Mexico.[183] The Court in New Mexico has held that the State Engineer has no obligation to enforce priority calls, as they are just one tool for managing water allocation.[184] Furthermore, the Court pointed out that in many cases in New Mexico, a priority call would be futile because water shortages are not the result of overuse, but rather the result of an arid desert climate.[185] The Court has not addressed whether a priority call made due to climate change-induced water shortages would ever be enforceable. Since the state has never implemented a priority call, and has no legal obligation to do so, it is highly unlikely that a priority call in New Mexico will ever be enforced.

Enforcement of a priority call requires that all rights in the stream or basin have been adjudicated.[186] Areas like the MRG are unadjudicated and will remain so for the foreseeable future, making priority calls impossible in many parts of the state that will see increased water stress due to SJCP delivery reductions.[187] Even in adjudicated basins, however, the State Engineer is not required to enforce priority calls, even though New Mexico state law provides a procedure for enforcing priority calls.[188]

While it may be in New Mexico’s interest to enforce a priority call on tribes, there are strong moral reasons to avoid this. Tribes would likely suffer serious consequences in the event of a priority call—both Navajo Nation and Jicarilla Apache have post-1950 priority dates due to settlement terms.[189] Thus, many non-native water users downstream in northern New Mexico could make a call on tribal water. This is troubling for two main reasons. Firstly, tribes were given only an illusion of choice in agreeing to later priority dates in settlements.[190] As was the case for both these tribal groups, development of infrastructure to deliver usable water was contingent on agreement to a later priority date.[191] For both Navajo Nation and Jicarilla Apache, this later priority date was almost a hundred years after the date of the federal reservation of the Winters right for each reservation.[192]

This change in priority date has consequences for potential calls on the SJCP allocation. Reductions in delivery affect the Navajo Nation before they affect water delivered to the Rio Grande because, per the settlement, the amount of water transferred via the SJCP was artificially inflated to 135,000 AF to appease the ABCWUA. When shortages are implemented, Navajo Nation’s actual water deliveries are reduced and the SJCP water deliveries are not physically reduced until reductions hit the actual 96,000 AF being delivered annually.[193] In order to guarantee funding to develop any water right at all, both the Navajo Nation and Jicarilla Apache were essentially forced to accept the later priority dates. It would be unjust to subject tribes to priority calls enforcing priority dates that were determined in objectively unfair circumstances. The second reason that New Mexico should not enforce a priority call against tribes with later priority dates is that this action runs counter to respecting tribal sovereignty. After hundreds of years of repeated violations of tribal sovereignty, New Mexico has an opportunity to honor tribal sovereignty over tribal land and tribal water.

Finally, New Mexico has no historical or cultural history of priority calls in the way Colorado or California does.[194] Water shortages are often managed collaboratively, as in the repartimiento of acequias or the shortage sharing implemented in the AWRM.[195] Even the MRGCD has created a unique system of tiering water priorities that reflects the unique values and history of the region, outside of state control.[196] The MRGCD treats MRG Pueblo rights as prior and paramount, since Pueblos have the right to water from time immemorial.[197] This water is administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.[198] The next most senior group are those in the MRGCD who hold individual water rights for usage on their land. Within this group, shortages are shared among the water rights holders. Finally, any remaining water in a shortage year goes toward the water bank water rights.[199]

In summary, while the state constitution codified the doctrine of prior appropriation, this was done mostly to incentivize Reclamation to fund large-scale water storage projects like Elephant Butte, rather than to actually implement a new water allocation system.[200] The Supreme Court of New Mexico has made it clear that it will never require the State Engineer to enforce a priority call and the State Engineer is under no obligation to enforce priority calls.[201] In Bounds v. State, the Court declared, “[t]he Constitution’s priority doctrine establishes a broad priority principle, nothing more. The prior appropriation provision is not self-executing.”[202] Despite this, the state constitution still lists the priority system as the mechanism for establishing water rights.[203] Without meaningful enforcement requirements, this section of the constitution is effectively mooted. New Mexico uses prior appropriation in name only, and thus the system as it is implemented in other states is ineffective here. Instead, New Mexico should take steps now to codify a shortage-sharing system that more accurately reflects the values of the state and anticipates future shortages. Because any water management authority has an obligation to make policy choices that are in the best interest of its users, the state should further develop its unique system for managing water shortages that balances the expectations of senior water rights holders with the realities of unenforceable priority dates.

5. It is not currently viable to use Active Water Resources Management administered by the OSE to mitigate the consequences of SJCP losses, but there may be opportunities in the future.

The state is likely unable to develop basin or district specific protocols under AWRM to manage SJCP shortage losses for two main reasons. First, SJCP water is used in the MRG, an area without existing AWRM controls.[204] AWRM implementation is limited to the previously identified priority stream systems and cannot easily be implemented in other systems.[205] Therefore, any water losses from SJCP shortages cannot be compensated or managed through AWRM. Second, SJCP water cannot be managed by the OSE since it is federal water rather than state water.[206] OSE’s only role in SJCP management is to ensure that only SJCP contractors use the SJCP water.[207] SJCP contractors, however, may use SJCP water to extinction since it is allocated entirely to the contractors and is not intended to flow to Elephant Butte.[208] Similarly, Albuquerque has strict controls on their senior pumping right plus junior pumping with conjunctive management system, using their SJCP allocation to replenish water.[209] Albuquerque, like other SJCP contractors, is allowed to use San Juan-Chama to extinction.[210] AWRM does not have mechanisms in place to manage SJCP water in the MRG in a meaningful way.[211]

While existing AWRM structures are ineffective for responding to SJCP shortages, New Mexico has historically been creative with drafting and implementing accounting swaps which allow the state to manage SJCP water and native water conjunctively. The “storage” of SJCP water in Elephant Butte Reservoir, downstream of its users, is one example.[212] When use of the water is called for, San Juan-Chama users simply withdraw native water from the Rio Grande, and an accounting change is made for the water at Elephant Butte, changing its designation to native.[213]

6. Acequias provide a model for water shortage sharing within communities.

Acequia management principles provide a meaningful alternative to prior appropriation. Rather than relying on an adversarial system, in which water right adjudication pits neighbors against each other, acequia systems are managed collaboratively.[214] Currently, acequias are considered political subdivisions within the state of New Mexico.[215] Unlike water rights in which conveyances are established individually, acequia conveyances (commonly referred to as ditches) are held in a tenancy-in-common by the landowners who use the water conveyed by the ditch.[216] This shared water management philosophy runs directly contrary to the rugged individualism epitomized in the prior appropriation system but appears to be much better adapted to a western climate with extreme variability in water availability.

The legally codified components of acequia management still utilize key components of prior appropriation with some marked differences. The formation of an acequia requires a man-made diversion from a stream, which is a longstanding principle in prior appropriation.[217] Additionally, acequias require the use of the water conveyed in the diversion to be put to beneficial use through some type of irrigation.[218] These principles appear to be durable across multiple management frameworks, but beyond this, prior appropriation and acequias diverge significantly.

As codified, acequias are protected from many traditional OSE actions. As an example, acequias do not require a permit for changing a point of diversion,[219] which contrasts sharply with other water users in New Mexico who must undergo a lengthy permitting process to change points of diversion that involves quantifying how much water is being used at the original point of diversion.[220] The general principle requiring permitting for changing points of diversion is intended to protect against new harm to other water users, but it rests on the previously discussed assumption that water users are adverse to one another.

Acequias are also protected from certain OSE actions, including the purchase of acequia water rights for use in New Mexico’s strategic water reserve.[221] This is significant because it protects acequia water from state acquisition. Within acequias, however, there exists internal water banking. In 2003, the state legislature created a law that permits individual acequias to establish internal water banks.[222] These water banks essentially function to redistribute an individual parciante’s annual water usage to the rest of the acequia water users in years where the parciante forbears use of their right.[223] This is critical because it protects water rights for lands that are not irrigated in a certain year from penalties for nonuse since other parciantes redistribute the water for their beneficial use.

These New Mexico codifications are critical because acequias predate the system of prior appropriation.[224] The concept of priority calls was introduced with the genesis of the prior appropriation system. Before prior appropriation, water shortages in Europe and the Eastern United States were shared evenly across users in the riparian system.[225] As in the riparian system, acequias generally share shortages, rather than enforcing priority dates in a system sometimes referred to as “repartimiento.”[226] While non-impairment of other users is sometimes recognized within individual acequias, it is not codified across the acequia system.[227] In the same way that prior appropriation is intended to prevent overuse of stream systems, acequias address overuse by allowing existing acequia communities to object to proposed new uses of water outside or in addition to the existing acequia system. Notably, these systems are based on equity, rather than priority.[228]

The New Mexico Acequia Association (“NMAA”) acknowledges how shortage-sharing principles can avoid the pitfalls of priority calls, stating “acequias on the same stream have avoided priority date issues because they have an established system for rationing or sharing water between different acequias regardless of priority dates.”[229] In this way, priority calls are entirely replaced.[230] These systems are opposed to one of the fundamental principles of western resource management, which focuses on the extraction of resources from the land. The NMAA also states that acequias are generally opposed to “marketing or selling water rights off the acequia,”[231] which also runs counter to the capitalist principles under which water is generally managed in the West.

Adopting acequia-based principles for water management would likely require a cultural shift, but anthropogenic climate change is already forcing changes in water management philosophies, regardless of the readiness of the necessary adopters. On April 11, 2023, Reclamation released a draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (“SEIS”) that addressed the reduced water levels on the Colorado River.[232] Among the three options proposed by Reclamation, the option that stood out proposed implementing water delivery reductions equally among all of the Colorado River Lower Basin states (Arizona, Nevada, and California).[233] In response, a letter released in May 2023 written by Lower Basin states offered Lower Basin water usage forbearance in exchange for a significant price.[234] This short-term solution provides no long-term vision for a future with less water.

The shortage-sharing regime proposed by Reclamation mimics many of the characteristics of the repartimiento practiced by acequias, with one key difference. Whereas repartimiento is agreed-upon by parciantes, this proposed shortage-sharing was met with sharp criticism from the largest municipal water user affected by the draft SEIS.[235] The criticism from water users within California notes that any reduction in water uses would cause significant hardship to individual water districts in California.[236] Notably, the criticism ignores the consequences of California “getting their way” and making most of Arizona unlivable due to water reductions. The agreement described in the Seven States Letter models shortage sharing to the cost of 1.8 billion dollars, which is not a sustainable long-term solution.[237]

Acequia water management philosophy rests on the principle of “[d]efend[ing] and protect[ing] our precious water by resisting its commodification and contamination.”[238] California could take note of this philosophy, particularly the resistance of commodification. In times of water shortage, all water users in a system will be harmed to some degree. The acequia management philosophy understands this and holds that shortages be shared equitably, rather than thrust upon neighboring users. This model is meaningful far outside the boundaries of New Mexico.

7. New Mexico’s existing frameworks are robust, but the state should transition away from using a prior appropriation system and codify a more enforceable water management code that reflects the cultural values of the state.

The broad challenges of meeting possible Colorado River shortages are mirrored in New Mexico’s water management obstacles. Just as prior appropriation does not serve the Colorado River Basin broadly, it does not serve New Mexico, as demonstrated in the above analysis. New Mexico has a cultural history of water shortage sharing, which draws a strong contrast from many other western states like California. As water shortages in the West continue to worsen, shortage sharing will be a critical part of water management. While prior appropriation has been durable up until this point,[239] stationarity no longer exists. Stationarity is using past data and norms to predict future outcomes.[240] However, we have no past data that reflects our current reality. If existing norms are no longer effective for managing water shortages, then existing legal structures will also be ineffective. Prior appropriation reflects a culture of stationarity. Fortunately for New Mexico, within the state, there are flexible systems of water management that allow water users to adapt collaboratively to reduced water availability. Acequia water management presents a community-centric model for shortage sharing, repartimiento. Similarly, the MRGCD also exemplifies a collaborative water governance system that does not rely on priority calls. The New Mexico state legislature should modify prior appropriation as it is codified in the state constitution to eliminate formal priority calls. Instead of priority calls, the state can instead look to these water-sharing models that more accurately reflect the cultural values of the state and share the inevitable economic burdens of reduced Colorado River water deliveries.

The world’s major greenhouse gas producers are not likely to reduce emissions in time to prevent significant global temperature increases.[241] This warming will continue to impact water availability in the Colorado River Basin, particularly in those areas that are predicted to warm by 2.5 to 5.5 degrees Fahrenheit by 2070.[242] There is no scientific evidence indicating that the aridification in New Mexico will improve,[243] which has potentially serious consequences for Colorado River deliveries across the northern part of the state. While these risks are troubling, New Mexico will be in a much stronger position if the state acknowledges the weaknesses of its existing Colorado River water allocation framework, as well as how those weaknesses will impact vulnerable communities, like tribes.[244]

Although New Mexico and many other Colorado Basin States have chosen not to publicly discuss internal risk mitigation for reduced Colorado River deliveries because of climate change, the risks to the public remain. The calculus for not releasing or developing these plans relies on the legal argument that if a state, such as New Mexico, demonstrates that there is a way to meet the state’s water needs with less water or by reducing the water needs, other states will use these calculations and contingency plans to demonstrate that the well-prepared state does not need the amount of water to which they are currently entitled. Although we understand the concern of this argument, none of the relevant compacts in the Law of the River list contingencies for water allocation. The current climate crisis was not anticipated by any of the compacts, and thus stationarity is no longer appropriate.[245] Though the compacts were necessary for the development of the infrastructure that would follow, the governing laws are insufficient and should not be discussed only behind closed doors. Transparency in communication with both New Mexico residents and other states would set the standard for collaborative interstate water management. Furthermore, it would allow New Mexico water users to prepare and adapt in advance of necessity forcing such measures. New Mexico and the rest of the Colorado River Basin is facing a drier, warmer future, but adaptation to these conditions is achievable through a combination of existing water management systems and the development of more robust water management frameworks.

- *Katherine H. Tara is a Staff Attorney and Water Policy and Governance Analyst in the Utton Center at the University of New Mexico School of Law. They are grateful to Adrian Oglesby, Reed Benson, J. Spenser Lotz, Aidan Manning, and Matthew Haney for their perspectives and support. The first draft of this paper was written for Gabe Pacyniak’s Climate Change Writing Seminar. ↑

- **John Fleck is Writer in Residence in the Utton Center at the University of New Mexico School of Law, and Professor of Practice in Water Policy and Governance in the University of New Mexico Department of Economics. He extends thanks to Eric Kuhn for his help in understanding Colorado River Basin governance. ↑

- Press Release, U.S. Geological Surv., Future Peak Flows Along Rio Grande May Arrive Early Due to Climate Change (Feb. 2, 2022), https://www.usgs.gov/news/state-news-release/future-peak-flow-along-rio-grande-may-arrive-early-due-climate-change. ↑

- Rio Grande at Alameda Bridge at Alameda, NM, U.S. Geological Surv., https://waterdata.usgs.gov/monitoring-location/08329918/ (last visited Feb. 21, 2023). ↑

- U.S. Geological Surv., supra note 1. ↑

- Act of June 13, 1962, Pub. L. 87-483, 76 Stat. 96 (1963); 43 U.S.C. § 620 (2009). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id.; U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, San Juan Chama Deliveries Spreadsheet (2021) (on file with author). ↑

- Act of June 13, 1962, Pub. L. 87-483, 76 Stat. 96 (1963); 43 U.S.C. § 620 (2009). ↑

- Lee Ferry is the official measurement point for deliveries to the Lower Basin, one mile below the confluence of the Paria and Colorado Rivers. Lee’s Ferry is the historical point for river crossings on the Colorado, further north from Lee Ferry. The U.S. Geological Survey named this point “Lees Ferry”, without the apostrophe on maps. See Lee Ferry, Water Educ. Found., https://www.watereducation.org/aquapedia/lee-ferry (last visited Apr. 3, 2023). ↑

- U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Scoping Meeting CR Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement – November 29, YouTube, at 32:01 (Dec. 5, 2022), https://www.youtube. com/watch ?v=i6oCohO6hk8&t=1s; U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Scoping Meeting CR Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement – December 2, 2022, YouTube, at 30:51 (Dec. 5, 2022), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=95qlAdCydD0. Slides with the figures showing the supplemental Environmental Impact Statement with modeling scenarios showing cumulative delivery dropping are visible in the November and December presentation videos, though they have been removed from the website. The 2023 water year delivered an unexpectedly high runoff, however, it is unlikely that this temporary reprieve reflects a long term change in reductions in Colorado River flow. ↑

- Colorado River Compact, art. III (1922); See also Colorado River Compact Approval, 43 U.S.C. § 617l (2022). ↑

- Letter from J.B. Hamby, Chairman, Colo. River Bd. of Cal., to Tommy Beaudreau, Deputy Sec’y, U.S. Dep’t Interior, Tanya Trujillo, Deputy Assistant Sec’y, U.S. Dep’t Interior, and Camille Touton, Comm’r, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (Jan. 31, 2023), https://crb.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/California-SEIS-Submittal-Package_ 230131.pdf. ↑

- Upper Colorado River Basin Compact, Pub. L. 81-37, 63 Stat. 31 (1949) (codified at Colo. Rev. Stat. § 37-62-101 (2012)). ↑

- Id. at art. III, IV. ↑

- Id. ↑

- U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, San Juan Chama Deliveries Spreadsheet (2021) (on file with author). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Casa San Ysidro, Pueblo Agriculture, at 3, 12, City of Albuquerque, https:// www.cabq.gov/artsculture/albuquerque-museum/casa-san-ysidro/documents/museum-lesson-pueblo-agriculture.pdf (last visited Jul. 26, 2021). ↑

- José Rivera, Acequia Culture 166–71 (1998). Paula Garcia, Repartimiento: Water Sharing in Times of Drought, N.M. Acequia Ass’n (Mar. 20, 2012), https://lasacequias.org/2012/03/20/repartimiento/. ↑

- Brigette Buynak & Adrian Oglesby, Basic Water Law Concepts, 2015 Water Matters! 1-3. ↑

- Ed Merta, Priority Administration, 2015 Water Matters! 10-4 to 10-5. ↑

- Douglas E. Beeman, As the Colorado River Shrinks, Can the Basin Find an Equitable Solution in Sharing the River’s Waters? Water Educ. Found. (Jan. 14, 2022), https://www.watereducation.org/western-water/colorado-river-shrinks-can-basin-find-equitable-solution-sharing-rivers-waters. ↑

- Vincent Ostrom et al., The Organization of Government in Metropolitan Areas: A Theoretical Inquiry, 55 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 831, 831 (1961). ↑

- Brigette Buynak & Adrian Oglesby, Basic Water Law Concepts, 2015 Water Matters! 1-3. ↑

- See Irwin v. Phillips, 5 Cal. 140, 146 (Cal. 1855). ↑

- Id. at 146–47. ↑

- 2022 Water Right Curtailments Fact Sheet, Cal. Water Bds., https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/drought/resources-for-water-rights-holders/docs/curtailments-2022.pdf (last visited Sept. 22, 2023). ↑

- David P. Billington et al., The History of Large Federal Dams: Planning, Design, and Construction in the Era of Big Dams 10 (2005). ↑

- Buynak & Oglesby, supra note 19. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Elephant Butte Reservoir was built using federal funds and the project was overseen by Reclamation. The implementation of Prior Appropriation was necessary because Elephant Butte made Reclamation the water management entity for water delivered out of Elephant Butte and Reclamation was unwilling to use a system other than prior appropriation. Id. at 1–5. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Felix S. Cohen, Handbook of Federal Indian Law 384 (1942). ↑

- Anastasia S. Stevens, Pueblo Water Rights in New Mexico, 28 Nat. Res. J. 535, 570 (1988). ↑

- Id.; see also Richard W. Hughes, Pueblo Indian Water Rights: Charting the Unknown, 57 Nat. Res. J. 219, 233 (2017). ↑

- Michael Osborn & Darcy S. Bushnell, American Indian Water Rights, 2015 Water Matters! 5-2. ↑

- Buynak & Oglesby, supra note 19. ↑

- Osborn & Bushnell, supra note 37. Water right for Pueblos are established under a different standard. See Aamodt Litigation Settlement Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-291, 124 Stat. 3064, 3134–56 (Dec. 8, 2010). ↑

- Colorado River Compact, Water Educ. Found., https://www.watereducation. org/aquapedia-background/colorado-river-compact (last visited Sep. 19, 2023). A Compact is an interstate agreement on water allocation, ratified by Congress and enforced by the Supreme Court aided by a Special Master in the event of a dispute. ↑

- 43 U.S.C. § 617l. ↑

- Colorado River Compact, art. III. ↑

- Connie A. Woodhouse et al., Updated streamflow reconstructions for the Upper Colorado River Basin, 42 Water Res. Rsch. 1 (2006). ↑

- See Ray L. Wilbur & Northcutt Ely, The Hoover Dam Documents A109 (1948). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at A110–11. ↑

- Beeman, supra note 21. ↑

- 63 Stat. at 31. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 33. ↑

- This figure assumes that the Upper Colorado River Basin uses their entire 7.5 MAF of Colorado River water in a year. Realistically, the Upper Basin has never developed their full allocation of 7.5 MAF, though for many years New Mexico did receive their full SJCP allocation. I choose to use figures rather than percentages to help conceptualize the quantity of water, since percentages can be hard to conceptualize. I got this figure by doing arithmetic. ↑

- Wilbur & Ely, supra note 44 at A110–11; U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, supra note 15. ↑

- U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, supra note 15. Development of a water right refers to the creation of infrastructure that allows the right holder to make use of the “wet” water. Without infrastructure, a water right is just “paper water”. ↑

- U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, supra note 15; Act of June 13, 1962, Pub. L. 87-483, 76 Stat. 96 (1963); 43 U.S.C. § 620 (2009). ↑

- Eric Kuhn & John Fleck, Science Be Dammed 10 (2019). ↑

- National Water Information System: Mapper, U.S. Geological Surv., https:// maps.waterdata.usgs.gov/mapper/index.html?state=nm. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Kuhn & Fleck, supra note 55. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- San Juan-Chama Project, U.S. Bureau Reclamation, https://www.usbr.gov/projects/index.php?id=521 (last visited Apr. 4, 2023). ↑

- See Kuhn & Fleck, supra note 55, at 151. ↑

- 76 Stat. at 96. ↑