Abstract

Twenty-plus years of drought and overuse in the Colorado River system have dramatically changed the outlook for water users in the system’s Lower and Upper Basins. At the time of this Article’s writing, the United States Bureau of Reclamation was simultaneously working on two related, but separate, environmental review processes related to the management of the Colorado River and its major storage reservoirs. The river system was granted a short reprieve in the form of a long overdue and above-average snowpack in the winter of 2022–2023, but all signs point to continued risk presented by an imbalance in the system caused by climate change and overuse.

This Article explores many (though not all) of the legal, political, and policy questions facing the system. Among the questions that bear on the risk of a potential Colorado River Compact (“1922 Compact” or “Compact”) curtailment are: (1) whether the consumptive use of tributaries within the Lower Basin count toward that basin’s Colorado River Compact Article III(a) and III(b) allocation; (2) whether the term “surplus” in the Compact’s Article III(c) Mexican Treaty provisions applies to System water in excess of 16 million acre-feet (“MAF”), or to the volumes allocated to each basin on an individual basis; (3) whether the Upper Basin’s Article III(d) non-depletion obligation is effectively excused if the flow at Lee Ferry falls below the ten-year running average requirement due to the impacts of climate change (instead of increased Upper Basin consumptive uses); and (4) whether the State of Colorado should pursue parallel strategies to prepare for an uncertain future or focus on addressing the current system inequities through litigation.

Without assuming a definitive answer to these hotly contested issues, the Article explores the potential impacts in the event that curtailment of water users within Colorado became necessary to ensure continued compliance with the Colorado River Compact. The views expressed are the author’s alone and do not represent the position of the State of Colorado or any other entity.

Table of Contents

Introduction 276

I. Colorado River Compact 280

II. The Upper Colorado River Basin Compact 292

III. The Risk of a Future Compact Deficit 296

IV. Pathways from a Compact Deficit to a Curtailment 298

V. Potential Consequences of a Curtailment for the State of Colorado 303

VI. Unique Issues Related to the Impacts of a Curtailment on Transmountain Diversions 307

VII. The Impacts to Colorado of a Curtailment of Transmountain Diversions 314

Conclusions 316

In 1985, former University of Colorado Law School Dean, David Getches wrote, “[t]he ultimate problem for the Upper Basin is how to build a future on the right to leftovers.”[2] A year later, Colorado water lawyer John U. Carlson and his associate, Alan E. Bowles Jr., amplified and expanded on Getches concerns: “[T]he Colorado River Compact of 1922, materialized principally as a result of fear of a recurrence of floods that devastated parts of the lower River in 1905–07 and again in 1916. Ironically, the condition which has most troubled the Law of the River since its inception has been the opposite problem: insufficient quantities of water,” adding that “the burden of these deficiencies is often assumed to fall on the states of the Upper Basin.” [3]

In the mid-1980s, when these seminal papers were written, the Colorado River system was quite literally overflowing with water. The large federal reservoirs were full and spilling. On the lower River, the mammoth Central Arizona Project, which by itself can divert over twelve percent of the river’s natural flow, was a decade away from finishing construction. The population of the Las Vegas area (Clark County) hovered around 500,000.[4]

Back home, in 1985, Colorado’s population had just surpassed 3.2 million.[5] The water community was engaged in a “roundtable” process convened to find consensus solutions for meeting the future water needs of the Front Range. The Denver Board of Water Commissioners (“Denver Water”) was trying to obtain federal permits for Two Forks Reservoir, a proposed 1 MAF storage facility located on the South Platte River southwest of Denver. While located on the East Slope, most of the water that would fill Two Forks would be diverted from the Colorado River System. Further, the construction of Two Forks would serve as an afterbay for the expansion of Denver’s Blue River Collection System. Denver Water had plans to collect water from the East Slopes of the Gore Range, the Piney River, and the tributaries of the Eagle River and then move it by canals and tunnels back to Dillon Reservoir where it would be delivered to Two Forks via the Roberts Tunnel. Denver Water’s plans, and other transmountain projects, such as the Windy Gap Project (operated by Northern Water’s Municipal Subdistrict) and the expansion of the Homestake Project, (which was being proposed by Colorado Springs and Aurora) showed that Front Range water planners had a clear plan for meeting their future needs: more Colorado River water. [6]

Four decades later, river conditions have changed in profound ways. The combination of climate change and overuse in the Lower Basin has drained the River system’s big reservoirs, Lakes Mead and Powell, to critically low levels.[7] Meanwhile, basin-wide growth and the demand for Colorado River water have continued unabated. The metropolitan Las Vegas area is approaching 3 million and the Central Arizona Project delivers approximately 1.5 MAF per year to 6 million people in Central Arizona.[8] Two Forks Reservoir was never permitted but Colorado’s population growth continued. Today there are nearly six million people in the state, with approximately eighty-five percent of them residing on the Front Range.[9]

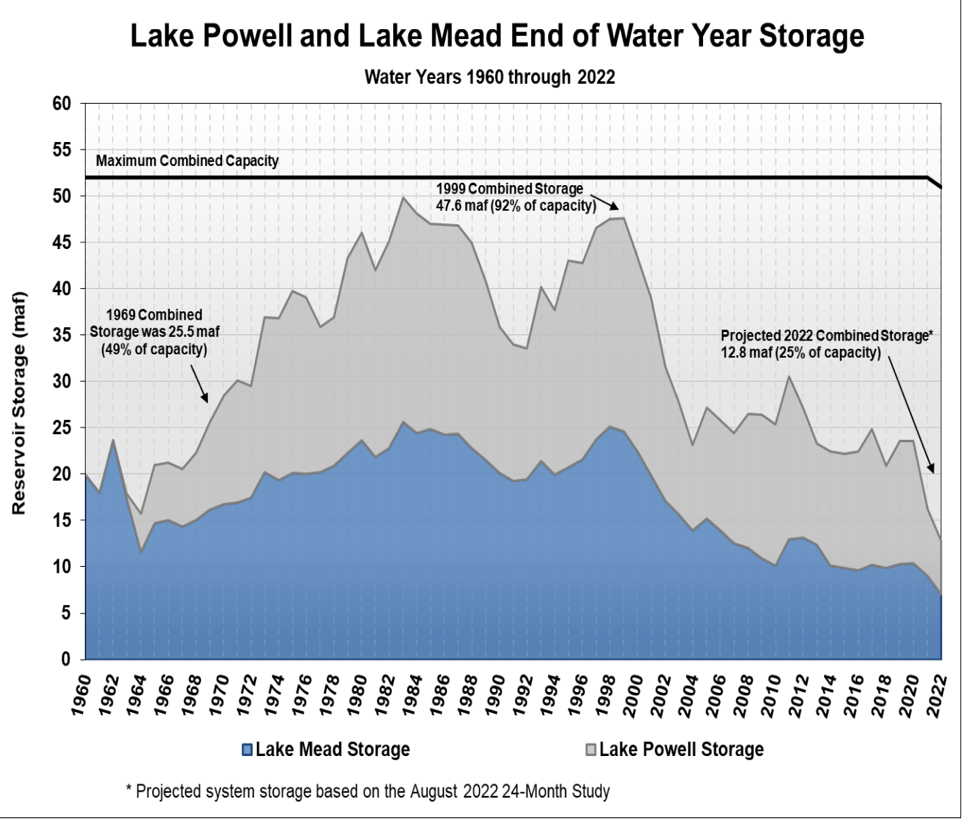

To reduce the drawdown of system storage and begin the process of reaching sustainability, the Lower Division States have had to implement major crop fallowing and conservation programs. In 2000, mainstem water deliveries from Lake Mead to Lower Basin users exceeded 8 MAF. In 2023, it was less than six million. The Upper Division States have, so far, avoided large mandatory cutbacks but, without the benefit of the Lower Basin’s major upstream storage, users in Upper Basin have had to live with significant hydrologic shortages. Figure 1 is a graph showing storage in Lake Mead and Lake Powell from 1960–2022. At the beginning of Water Year 2000 (October 1, 1999) total storage in these two reservoirs was 47.6 MAF (ninety-two percent). By the end of Water Year 2022, storage had dropped to 12.8 MAF (twenty-five percent). A precipitous drop in storage caused by total demands for water in the basin exceeding the available water supply by about 1.5 MAF per year. In 2023, reservoir levels recovered somewhat due to the abundant runoff from the wet winter of 2022–2023. Total storage in Lakes Mead and Powell as of December 31, 2023,  was 17.5 MAF (thirty-four percent).[10]

was 17.5 MAF (thirty-four percent).[10]

Figure 1[11]

In the 1980s, the policy questions that concerned Getches, Carlson, and Bowles were related to water for future growth. Were the Colorado River “leftovers” available under the “inequities” of the Law of the River sufficient to meet future needs of Colorado and its sister Upper Division States? Today, because of the impact of climate change on the River’s flows and escalating basin-wide demands for water, the policy question is much more fundamental: are the leftovers even sufficient to meet current consumptive uses in Colorado and the other Upper Division States without triggering what is commonly referred to as a “compact call” or more formally a “curtailment?”

Colorado’s Front Range transmountain municipal water supplies are clearly at an elevated risk. All its major cities rely on water imported from the Colorado River basin to meet a major portion of their existing demands. Although transmountain diversions make up only about twenty percent of the State’s Colorado River use, they make up nearly fifty percent of Colorado’s water use under rights that are junior to the Compact.[12] Under the Law of the River, post-compact rights—both in-basin and transmountain uses—are at the most risk of facing a curtailment to meet the requirements of the Colorado River Compact. The curtailment of Colorado’s transmountain diversions coupled with the curtailment of critical post-compact uses on the West Slope, would create a major economic and political nightmare for the State. State water officials express public confidence that there is little or no risk of a future curtailment; however, when considered against the advice and concerns expressed by past experts like Getches and Carlson, a more cautious approach may be prudent.

A negotiated agreement that permanently eliminates or results in a curtailment only in extremely rare circumstances would obviously be preferred, but such an agreement may be very difficult to reach. To get there, the Upper and Lower Division States would have to agree to fundamental changes to the Law of the River. A short-term agreement may be more attainable, but likely would only put off the problem for the next generation. Litigation would be lengthy, expensive, and fraught with uncertainties. The best path forward should include reducing the interstate risk to the greatest extent possible while also carefully preparing to address the economic and political hardships presented by a potential curtailment.

The Colorado River Compact (“1922 Compact” or “Compact”) is considered the foundation of the “Law of the River.” The 1922 Compact was negotiated by commissioners appointed by the governors of each of the seven basin states and a federal commissioner appointed by the President of the United States. The commissioner from Colorado was Delphus E. Carpenter, a nationally respected water lawyer from Greeley, Colorado.[13] The federal commissioner and commission chairman was Herbert Hoover.[14] In 1922, Hoover was the Secretary of Commerce. In 1928, he was elected the thirty-first president of the United States, serving from 1929–1933.[15]

The 1922 Compact was signed by the commissioners on November 24, 1922. The ratification process was lengthy and difficult. Arizona’s legislature initially refused to ratify the agreement, forcing the remaining states to adopt a six-state strategy. The six-state strategy succeeded in December 1928, when Congress passed the Boulder Canyon Project Act (“1928 Project Act”). On June 25, 1929, President Herbert Hoover signed a proclamation declaring the 1928 Project Act effective. With this proclamation, the six-state 1922 Compact became effective. Arizona finally ratified the 1922 Compact in February 1944.[16]

The 1922 Compact defines the Colorado River System as “that portion of the Colorado River and its tributaries within the United States of America.”[17] The 1922 Compact divides the consumptive use of the Colorado River System’s waters between two geographic sub-basins; an Upper Basin, defined as the drainage area above Lee Ferry—the dividing point—and a Lower Basin, defined as the geographic area that drains into the river below Lee Ferry. Lee Ferry is defined as a point in the river one mile downstream of the confluence of the Colorado and Paria Rivers in Northern Arizona.[18] The 1922 Compact defines the Upper Division States as Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming and the Lower Division States as Arizona, California, and Nevada. Two Upper Division States, Utah and New Mexico, have lands in the Lower Basin and Arizona, a Lower Division State, has lands in the Upper Basin. [19]

Article III contains the operative hydrologic nuts and bolts of the 1922 Compact. Article III includes seven paragraphs. Paragraphs (a) and (b) apportion the beneficial consumptive use of the river system’s waters between the two sub-basins. Paragraphs (c), (d), and (e) contain the 1922 Compact’s “flow” or “non-depletion” provisions, and Paragraphs (f) and (g) provide for the further apportionment of any surplus water after October 1, 1963, which has not happened.

Article III(a) apportions to each sub-basin in perpetuity the exclusive beneficial consumptive use of 7.5 MAF per annum.[20] Article III(b) allows the Lower Basin to increase its consumptive use by an additional 1 MAF per annum.[21] There are differing opinions about the meaning and interpretation of both paragraphs. Historically, Article III(b) has been the most contentious. For example, in the 1952 Arizona v. California Supreme Court case, Arizona originally took the position that Article III(b) water was for its exclusive use, other than a small amount for the consumptive uses by New Mexico and Utah on their Lower Basin tributaries.[22] In its 1958 amended complaint, Arizona changed its mind, claiming that the 1922 Compact’s Lower Basin apportionments, including Article III(b), only apply to mainstem uses, and do not cover uses on the Lower Basin tributaries—despite the Compact’s plain language expressly including tributaries with the definition of the Colorado River System.[23]

In his December 1960 Report, the Special Master in the Arizona v. California case, Simon Rifkind, concluded that he did not have to interpret the 1922 Compact to dispose of the case; nonetheless, he included a background section on the 1922 Compact.[24] In this background section, he wrote “[i]t is my conclusion that Article III(b) has the same effect as Article III(a), and this conclusion is supported by the reports of the Compact commissioners, who spoke of III(a) and III(b) as apportioning 7,500,000 acre-feet to the Upper Basin and 8,500,000 acre-feet to the Lower Basin.” [25] There is considerable uncertainty concerning the interpretation of Article III(b), perhaps more so in the Upper Colorado River Basin.[26] From the onset a basic question was: Is Article III(b) intended to cover only beneficial consumptive uses on the Lower Basin tributaries or could it be used on the mainstem and the tributaries? In Commission Chairman Hoover’s written Congressional testimony, he specifically addressed this issue in response to Arizona’s Representative Carl Hayden; “the extra 1,000,000 acre-feet provided for can therefore be taken from the main river or from any of its tributaries.” [27] Regardless, the 1922 Compact is clear that the Lower Basin’s combined (mainstem and tributary) apportionment of non-surplus “System” water is limited to a total of 8.5 MAF per year.

Most recently, because of the impact of climate change on the natural flow of the Colorado River at Lee Ferry, there are differing views of Article III(a). [28] The paragraph, by its own text, apportions an equal amount of beneficial consumptive use to each sub-basin, 7.5 MAF per annum, raising the basic question: was it the intent of the negotiators of the 1922 Compact to give each sub-basin equal amounts of water for beneficial consumptive use from the mainstem of the Colorado River and its tributaries above Lees Ferry? The equal division argument fits with the position that Article III(b) covers Lower Basin tributary uses but may not fit with how legal experts and compact historians have interpreted the 1922 Compact. In his background section, Rifkind concluded: “I regard Article III(a) and (b) as a limitation of appropriative rights and not as a source of supply.” [29] In “The Colorado River” former Stanford University Law School Dean, Charles J. Meyers writes: “[t]he apportionment of Article III(a) and (b) of 7.5 million acre-feet to the Upper Basin and 8.5 million acre-feet to the Lower Basin is a limitation on use—a ceiling placed upon the ‘beneficial consumptive use’ of water from the Colorado River System—rather than a grant of specific quantities of water.”[30]

In Competing Demands, Getches explores the conflict between Article III(a), which apportions 7.5 MAF of consumptive use to the Upper Basin, and Articles III(c) and (d) which historically were read as a condition on the Upper Basin’s Article III(a) allocation, concluding: “the erroneous assumption [by the Compact’s drafters] about average flows resulted in the Lower Basin’s being guaranteed substantial minimum deliveries by the Upper Basin, leaving far less water available for Upper Basin use than the negotiators apparently expected.”[31] In “Contrary Views,” Carlson and Bowles explore the equity issue in detail. Although they write that it was probably the intent of the 1922 Compact negotiators to apportion to each sub-basin approximately equal amounts of water[32] and that it is unlikely that Congress would have approved the 1922 Compact without this equal division, they conclude that because of compact math, there is no longer an equal division. Carlson And Bowles conclude that the Upper Division States only have “faint hope for a resolution.”[33]

Article III(c) deals with the obligation of each basin to Mexico under the 1944 Treaty. In 1922, when the 1922 Compact was signed there was no treaty, but the commissioners understood that one was possible, if not likely.[34] Therefore, the commissioners wanted to address the issue up front. The Article provides that water for Mexico shall first be supplied from the surplus, which is defined as the amount of water over and above the 16 MAF of water apportioned in “aggregate” to each basin under Articles III(a) and III(b). If the surplus is insufficient then “the burden of such deficiency shall be equally borne by the upper basin and the lower basin, and whenever necessary the States of the Upper Division shall deliver one-half of the deficiency so recognized.”[35]

A significant dispute exists between the basins as to the application of the terms “deficiency” and “surplus” in Article III(c). The question is whether “surplus” means volumes over the total allocation of 16 MAF or to each basin’s allocation on an individual basis? Under the Upper Basin’s interpretation, any time that the Lower Basin’s consumptive use exceeds 8.5 MAF per year, a surplus in the amount of the overage exist—a position that would relieve the Upper Basin of any burden to cover one-half of the Mexican Treaty obligation. The Upper Division States have consistently taken the position that their obligation is currently undefined and there is no requirement to deliver 750,000 acre-feet every year.[36] Upper Division State officials point out that current Lower Basin consumptive uses, including mainstem uses, mainstem reservoir evaporation, and Lower Basin tributary consumptive uses exceed the 8.5 MAF per year apportioned to it under the 1922 Compact; they also note that this excess use must first be delivered to Mexico to meet the 1944 Treaty requirements before the States of the Upper Division have any obligation to deliver water at Lees Ferry for Mexico.[37]

The States of the Lower Division have, just as consistently, taken the position that there is no surplus and therefore, the States of Upper Division have an obligation to deliver fifty percent of the annual delivery to Mexico under the 1944 Treaty, normally 750,000 acre-feet per year to Mexico.[38] The Lower Division officials have written that “contrary to the Upper Division States’ view of Article III(c), the Lower Division States’ use of Colorado River water is irrelevant to the calculation of surplus or deficiency in Article III(c).”[39] A position that Carlson and Bowles apparently agreed with—“the Upper Basin’s position in this respect contravenes the express language of Article III(c) which provides that the Mexican Treaty water ‘shall first be supplied from the waters that are surplus over and above the aggregate of the quantities specified in paragraphs (a) and (b)…’”[40]

Article III(d) requires the Upper Division States to not cause the flow of the Colorado River at Lees Ferry to be depleted below 75 MAF every ten consecutive years. Until recently, that Article has not been considered controversial.[41] Because of the impacts of climate change, this may no longer be true. Many scientists have concluded that anthropogenic climate change has contributed to the reduction in annual natural flow of the Colorado River at Lees Ferry from a twentieth-century average of about 15 MAF per year to about 12.5 MAF per year over the first twenty years of the twenty-first century.[42] The impact of climate change on the flow of the river at Lee Ferry has raised a new fundamental question: if climate change, not just depletions by Upper Division States, is one of the primary causes that future flows at Lee Ferry fall below 75 MAF every ten years, is that a violation of the 1922 Compact?

The issue of “causation” is multifaceted. Climate change might be attributable to a reduction of about 2.5 to 3.0 MAF per year at Lee Ferry since 2000, whereas during that same period, Upper Basin depletions have averaged about 4.3 MAF per year,[43] giving the Upper Division States a reason to argue that if it were not for the impacts of climate change, Lee Ferry flows would not have fallen below the 1922 Compact’s non-depletion threshold. The counterargument by the Lower Division States would be that even factoring the impacts of climate change, the Upper Division States can satisfy the non-depletion obligation by curtailing Upper Basin uses.[44]

There is no specific provision in the 1922 Compact for a “compact call” or a “curtailment,” nor does the 1922 Compact provide for an agency or public official that has the power to declare that the Upper Division States are not in compliance with the 1922 Compact’s Articles III obligations. The assumption was that once the Compact became effective, disputes would be addressed under the dispute resolution provisions of Article VI, or alternatively, under Article IX, which allows a state to take “any action or proceeding, legal or equitable, for the protection of any right under this compact or the enforcement of any of its provisions.” [45]

Article III(e) prohibits the Upper Basin from withholding water that cannot be used for domestic and agricultural purposes and prohibits the Lower Basin from requesting the delivery of water that cannot be used for those same purposes (agriculture and domestic).[46] One of the primary reasons this provision was included in the 1922 Compact was that, in 1922, several proposals for large power-producing dams were pending before the Federal Power Commission (now the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission).[47] Delph Carpenter and his upper river colleagues feared that if permitted and built, such a project could put a legal call on the river for power purposes limiting the consumptive uses of water in the Upper Basin.[48] During a future interstate litigation scenario, however, it is possible that the parties could rely on Article III(e) to challenge a wider range of issues such as the deliveries of water to underground storage basins by the Lower Division States, and how much water is required to be reserved in storage in Lake Powell and the other initial units of the 1968 Colorado River Basin Projects Act in order to protect future uses in the Upper Division States under section 602(c) of that Act.[49]

In considering the impacts of a potential curtailment on water uses in the Upper Basin, two other Articles of the 1922 Compact need to be considered: Articles IV and VIII. Article VIII states that “present perfected rights to the waters of the Colorado River System are unimpaired by this compact.” This article is widely considered to mean that water uses under rights that were perfected before the 1922 Compact was signed or became effective would not be subject to curtailment to meet the Upper Division State’s Lees Ferry requirements, but like many other Compact articles, there are differences of opinion and potential disputes over its interpretation.[50]

Two such issues are the effective date of when rights are covered (the meaning of “present”) and what is meant by “perfected.” The 1964 Arizona v. California decision may provide some non-binding guidance on both questions.[51] The decision, which did not interpret the 1922 Compact, had to address the issue because Section 6 of the 1928 Project Act states that the project (Lake Mead) “shall be used: First, for river regulation, improvement of navigation, and flood control; second, for irrigation and domestic uses and satisfaction of present perfected rights in pursuance of Article VIII of said Colorado River compact; and, third, for power.”[52] In the March 9, 1964 decree implementing and carrying forward the 1963 decision, Article I(g) defines a “perfected right” as “a water right acquired in accordance with state law, which right has been exercised by the actual diversion of a specific quantity of water that has been applied to a defined area or to definite municipal or industrial works, and in addition shall include water rights created by the reservation of mainstream water for the use of federal establishments under federal law whether or not the water has been applied to beneficial use.”[53]Article I(h) defines “present perfected rights” as “perfected rights as here defined, existing as of June 25, 1929, the effective date of the Boulder Canyon Project Act.”[54]

The extended dispute in the Lower Basin demonstrates why the definition of present perfected rights is an important and contentious issue. During times of shortage, the decree requires the Secretary to first meet the water needs of present perfected rights (commonly referred to as “pre-Compact rights”) without regard to state lines. Thus, it affects the amount of water available to users with rights that are junior (commonly referred to as “post-Compact rights”). The more water that is delivered to pre-Compact rights means there is less available for post-Compact rights and, because they were the last to develop, the post-Compact rights include the water supplies for the Lower Basin’s major urban centers like Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Las Vegas. Conceptually, the same is true in the Upper Basin. Its major urban centers like the Denver Metropolitan Area, Utah’s Wasatch Front, and Albuquerque rely on water exported from the Colorado River under post-Compact water rights, but there are also major differences.

In the 1964 decision, the Supreme Court agreed with its Special Master that the case was a Lower Basin matter only, concluding that the 1928 Project Act was a Congressional apportionment of the waters available on the Lower Basin mainstem.[55] Colorado and Wyoming were not parties in the case.[56] Utah and New Mexico were parties but limited to their Lower Basin interests only.[57] Therefore, it can be argued that the details of how Article VIII applies to water rights in the Upper Basin and, arguably, the Lower Basin tributaries have never been disputed and have not been addressed by the Supreme Court.

Article VI of the 1964 decree required the States of Arizona, California, and Nevada to submit to the court and to the Secretary of the Interior specific data on present perfected rights within each state and for the Secretary to furnish similar information with respect to federal claims for present perfected rights.[58] The process of identifying and quantifying the present perfected rights on the Lower Basin mainstem was contentious and took another twenty years to reach a final agreement.[59]

Article IV of the 1922 Compact may be applicable here because it addresses issues that are internal to a state. It has three paragraphs: IV(a) declares that the Colorado River has ceased to be navigable for commerce;[60] IV(b) authorizes the storage and use of water for power generation, but makes such uses subservient to the use and consumption of such water for agricultural and domestic purposes; and Article IV(c) stipulates that the provisions of the article shall not apply to or interfere with the regulation and control by any state within its boundaries of the appropriation, use, and distribution of water.[61]

Within the States of the Upper Division, the issues related to the interpretation of present perfected rights may only affect other rights within an individual state. Provided that the Upper Basin as a whole is meeting its obligations under the 1922 Compact and each state is meeting its obligation under the Upper Basin Compact, does it matter if Colorado and Utah have a different definition of present perfected rights? This approach would be consistent with the intent of Article IV(c) of the 1922 Compact and a similar provision in the Upper Basin Compact, Article XV(c), discussed further below.

II. The Upper Colorado River Basin Compact

The Upper Colorado River Basin Compact (“Upper Basin Compact”) was signed by the five States with Upper Basin interests on October 11, 1948. It was quickly ratified by the States and approved by Congress, becoming effective on April 6, 1949. The Upper Basin Compact has two primary purposes: It apportions among the States of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming the beneficial consumptive use of the water apportioned to the Upper Basin by Article III(a) of the 1922 Compact and it makes provisions as to the responsibility of the States of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming (the Upper Division States) in regard to their joint obligation under Article III of the 1922 Compact. Interestingly, while the 1922 Compact provides that the Upper Basin has only a non-depletion obligation, the Upper Basin Compact contains several references to the Upper Basin’s obligation to deliver water at Lees Ferry.[62] To administer the Upper Basin Compact, it created an administrative agency known as the Upper Colorado River Commission (“UCRC”). It is the UCRC that has the formal power to declare a “compact call,” referred to as a “curtailment.”[63] The UCRC is composed of five commissioners, one from each of the four Upper Division States and one representing the United States. Arizona does not have a representative on the UCRC.[64]

The apportionments are made in Article III of the Upper Basin Compact. Arizona received a fixed apportionment of 50,000 acre-feet per year. The four Upper Division States were apportioned a percentage of the water “in perpetuity to and available for use each year by Upper Basin under the Colorado River Compact and remaining after the deduction of the use, not to exceed 50,000 acre-feet per annum, made in the State of Arizona.”[65] In his 1948 Compact report made to the Governor and General Assembly, Colorado Commissioner Clifford Stone was careful to explain why the Commission chose to apportion water to the Upper Basin States by percentage and to define the term “and available for use each year by Upper Basin”:

While the 1922 Compact, by its paragraph III(a), apportions to the Upper Basin the beneficial consumptive use of 7,500,000 acre-feet annually, such use is subject to the availability of water, The States of the Upper Division are required by the 1922 Compact to maintain certain flows at Lee Ferry. The water available for use in the Upper Basin is that remaining after the Lee Ferry delivery requirements are satisfied. In view of the uncertainty as to the total amount of water which might be available for the Upper Basin the Compact Commission determined that so far as the States of the Upper Division are concerned the apportionments must be in terms of percents of the total amount of water apportioned to, and available for use in, the Upper Basin.[66]

Utah’s Compact Commissioner Edward Watson used language identical to Stone in his report to the Utah Governor and General Assembly. The water that Stone and Watson refer to as “that remaining after the Lee Ferry delivery requirements are satisfied” was labeled by Getches, Carlson, and Bowels as the “leftovers.”[67]

The procedures for a curtailment of uses, if necessary, are provided for in Article IV. In his Compact report, Stone summarized the article as follows:

Article IV gives the administrative agency created by the Compact (UCRC) the authority to determine the extent of a curtailment as to quantity and time. In doing so, however, the Commission must follow certain stated principles. The curtailment must be such as to assure full compliance with the Colorado River Compact [Paragraph IV(a)]. If any States or States in the ten years preceding the year in which the curtailment is necessary, has used more water than they were entitled to under the apportionment made in Article III, then such State or States must deliver at Lee Ferry a quantity of water equal to the overdraft before demand is made of any other state for curtailment [paragraph IV(b)]. Except for this requirement, the extent of curtailment by each Upper Division State must be such as to deliver at Lee Ferry the quantity of water which bears the same relation to a total curtailment as the consumptive use of waters by that state bears the same relation as the total consumptive use of in all the States of the Upper Division during the same year. It is most important to note that in determining the last-mentioned relationship uses of water under rights perfected prior to November 24, 1922, are excluded [Paragraph IV(c)]. [68]

The Upper Basin Compact lists the principles that guide the decision to declare a curtailment, but important implementation details are left to the UCRC. Under the Upper Basin Compact, Article VIII, the UCRC has the power to adopt rules and regulations. The first and most critical question is what is meant by “full compliance with Article III of the Colorado River Compact”? Answering this question will require the UCRC to interpret compact issues that have been disputed for decades and make findings that, if one or more of the Lower Division States disagree, could result in litigation. The obligation of the Upper Division to Mexico under Article III(c) is one example.[69] The obligation of the Upper Division States to Mexico has been a long-standing dispute between the Lower Division and Upper Division States.

If the UCRC concludes that a curtailment is necessary, its next steps are to determine the amount and timing and distribute the curtailment among the four Upper Division States. Articles IV(b) and IV(c) control the distribution. The distribution process has the potential to be contentious. How the UCRC interprets these two Articles will determine the impact of the curtailment on each state. Once the UCRC sets the amount and timing and distributes the curtailment among the states, how a curtailment is administered within a state is left up to each state.

Based on data available from the Consumptive Uses and Losses Reports published by the Bureau of Reclamation, over the ten-year period of 2011–2020, Colorado consumed about fifty-five percent of the total consumptive use within the four Upper Division States.[70] Its apportionment is 51.75 percent.[71] Thus, even though the Upper Basin currently is in full compliance with the 1922 Compact, Colorado’s proportionate use can be seen as potentially heightening the risk to Colorado water users—if a compact curtailment were to be imposed at the current proportions of use by the Upper Division States, Colorado could run afoul of the so-called “overdraft penalty box” provision of Article IV(b) of the Upper Basin Compact. There are, however, many uncertainties. The Reclamation data are provisional, the method for determining irrigation consumptive use is in the process of being revised,[72] and importantly, the UCRC has not formally published rules and regulations governing how the article will be implemented.

For administering the provision of Article IV(c) which requires excluding consumptive uses from water rights perfected prior to November 24, 1922, from the determination of each state’s curtailment share, the critical question is what is meant by “perfected”? Is the amount to be excluded based on the amount of consumptive use attributable to the water rights as of 1922 or the amount those same rights are supporting at present? In the states that recognize conditional (or inchoate) rights, are present day uses from rights that were conditional in 1922, but absolute today, included? How should tribal rights, perfected under the 1908 Winters Doctrine,[73] be handled? The differences could be significant. It could potentially reduce or eliminate one state’s share of the curtailment, putting the burden on the other states. Related practical questions are what data are available and what level of documentation, or proof, will each state be required to submit to the UCRC?

The Upper Basin Compact sets forth principles for the UCRC to declare and administer a curtailment, but whether in a real-world situation that requires a curtailment, the UCRC can make and implement the process in a timely and politically acceptable manner to maintain full compliance with Article III of the 1922 Compact is a wide-open question. It is more likely that to get there, the UCRC will have to make decisions with incomplete, missing, or provisional data and the individual commissioners will have to make numerous compromises to achieve a consensus result. Formal action by the UCRC requires a “yes” vote by four members, but practically, a decision on a curtailment is such a major decision that it would likely have to be unanimous.[74]

III. The Risk of a Future Compact Deficit

Before the UCRC can declare a curtailment, it must determine or make a projection that the Upper Division States are not or will not be in compliance with the Lees Ferry flow requirements under Article III of the 1922 Compact.[75] The potential shortfall is commonly referred to as a “compact deficit.” There are different opinions as to what level of Lee Ferry flow would trigger a compact deficit. Historically, the obligation of the Upper Division States has been bracketed between a high of 82.5 MAF every ten consecutive years and a low of 75 MAF every ten years, but there are scenarios where it could be higher or lower. The high end, 82.5 MAF every ten-years, assumes the Upper Division States have an obligation to deliver 750,000 acre-feet per year to Mexico every year plus 75 million under III(d). The low end, 75 MAF every ten-years, assumes the Upper Division States have no obligation to Mexico and only have to comply with Article III(d), but there are other possibilities. The Lower Division States have, on occasion, suggested that the Upper Division States’ treaty obligation to Mexico also includes transit losses between Lee Ferry and the border with Mexico, which would increase the delivery obligation.[76] Further, most recently, Upper Basin water officials have suggested that there would be no compact violation if climate change is a contributing cause for Lees Ferry flows falling below 75 million every ten years.[77] Under the assumptions that the basin-wide hydrologic conditions experienced since 2000 continue or perhaps get drier and that the operating rules that govern annual releases from Glen Canyon Dam are pursuant or similar to the 2007 Interim Guidelines, a scenario where the ten-year flow falls below 82.5 MAF is very plausible.[78]

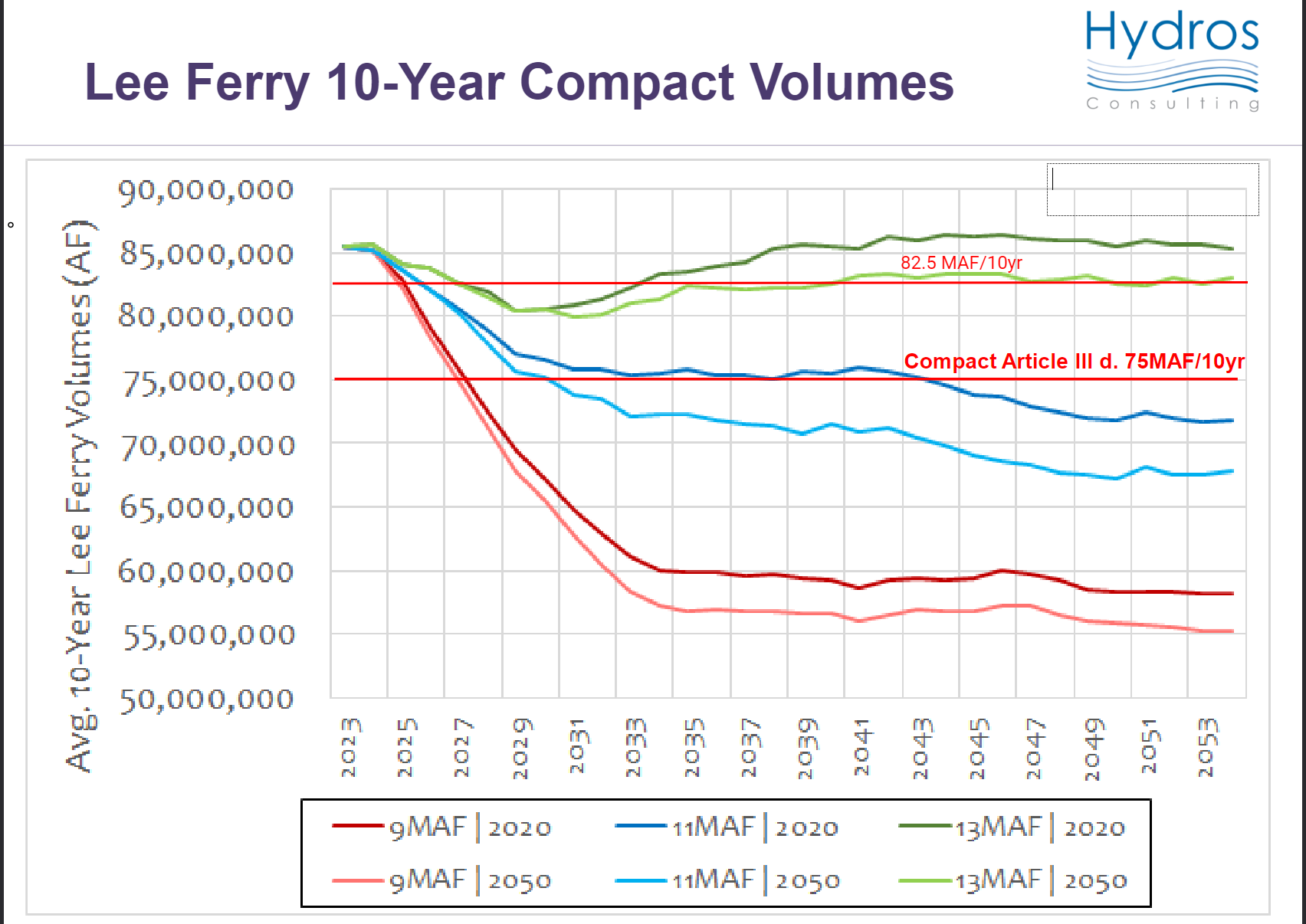

Based on data published in the UCRC’s seventy-fourth annual report, the ten-year flow at Lees Ferry for the 2013–2022 period was 85.6 MAF.[79] Updating the data for the 8.73 MAF of Lee Ferry flow in Water Year 2023 and assuming that Glen Canyon Dam releases for Water Years 2024–2026 are 7.48 MAF per year, the ten-year flow for 2017–2026 would be approximately 83 MAF.[80] If releases for 2027 and 2028 were to be 8.23 MAF, the 2019–2028 flow drops to approximately 81.5 MAF.[81] This scenario is consistent with river modeling conducted by Hydros Consulting for Phase IV of the Colorado River Basin Risk study sponsored by the Colorado River Water Conservation District and Southwestern Water Conservation District.[82]

Figure 2 shows the modeling results for ten-year Lee Ferry flows under three different natural flow[83] assumptions at Lees Ferry and two different Upper Basin demand assumptions. Under all six model runs, the median ten-year deliveries drop below 82.5 MAF.[84] Under the two dry scenarios, 11 and 9 MAF per year, median ten-year deliveries drop below 75 MAF. Under the model run that most closely represents twenty-first century conditions, 13 MAF per year of natural flow and 2020 development levels (the top dark green line), median ten-year deliveries drop below 82.5 MAF per year around Water Year 2027.

These model results suggest that, if over the next decade average annual natural flows at Lee Ferry are about 13 MAF or less, there is a substantial risk that ten-year flows could fall below 82.5 MAF. Further, if average annual natural flows drop to a level approaching 11 MAF per year, there is a substantial risk that ten-year flows could drop below 75 MAF per year.[85] The modeling results also clearly show that future growth in Upper Basin consumptive uses increases the risk of a compact deficit.

Figure 2 Phase IV Risk Study Model Results[86]

IV. Pathways from a Compact Deficit to a Curtailment

If in the future, ten-year Lee Ferry flows were to drop below 82.5 MAF and the situation is not specifically addressed in Reclamation’s post-2026 operating rules (the operating rules that will replace the currently applicable 2007 Interim Guidelines), it could trigger a governance crisis on the Colorado River System. In their August 15, 2023, comment letter to Reclamation on the Environmental Impact Statement (“EIS”) for scoping of the post-2026 reservoir operations, the three Lower Division States requested:

[T]he Post-2026 EIS must analyze whether alternatives are consistent with the 1922 Colorado River Compact non-depletion obligations and delivery obligations to Mexico. Alternatives should include actions necessary to ensure compliance with this provision.[87]

The obvious problem with the request, which the Lower Division States fully understand, is that there is no consensus among the States on the interpretation of the non-depletion obligation (Article III(d)) and the basins’ respective delivery obligations to Mexico (Article III(c)). For the EIS, Reclamation may decide to bracket these obligations between 75 and 82.5 MAF every ten years, but it is unlikely that Reclamation can do more than that.

A potential alternative approach to avoiding a crisis upfront would be for the Basin States to agree that if the reservoir system is being operated in accordance with the new post-2026 operating rules, all seven states will refrain from making a claim that there is a violation of the provisions of Article III of the 1922 Compact. Whether all seven States and perhaps the United States would, or legally could, agree to such an agreement is an open question.[88] Additionally, there may be valid policy reasons for both the Upper Division and Lower Division States to reject such a proposal. The next set of “interim” operating guidelines will likely have a term of fifteen to twenty-five years. If the Upper Division States agree to a strategy that again finesses or postpones resolution of disputed Lee Ferry compact obligations, will they be in a better position to resolve the disputes in their favor in the future when the post-2026 guidelines expire? If the answer is no, the better approach may be to push for resolution as a part of the ongoing negotiations.[89]

Assuming that there are no provisions in the post-2026 operating guidelines addressing a situation where ten-year flows at Lee Ferry drop below 82.5 MAF, the Basin States and federal government have four interrelated basic approaches to resolving the potential governance crisis.

The first, and perhaps most likely, approach would be a short-term agreement that is written and implemented so that it does not prejudice the legal positions of either the Upper Division or Lower Division States. Finding physical solutions may be easier than addressing long-standing legal and political issues. For small deficits, less than 100,000 to 300,000 acre-feet—amounts that might be within the precision of the forecast[90]—an acceptable approach may simply be to wait to see what happens. A wet spring (2015), an abundant summer and fall monsoon (2006), or a subsequent wet winter (2023) could make it much easier to find acceptable solutions.[91] The downside to a “wait and see” approach is that any potential compact deficit may get larger, making it more difficult to find short-term solutions.

For larger deficits—300,000 to 500,000 acre-feet or more—finding a short-term agreement could be more problematic. Physical solutions may exist, such as delivering the deficit from the storage available in Flaming Gorge Reservoir or, though less likely, Blue Mesa Reservoir. However, it is likely one or more of the states may not like the precedent the proposed short-term agreement sets.[92] The Upper Division States may not want to ever agree to a ten-year flow target of 82.5 MAF, even with carefully crafted “disclaimer” language. The Lower Division States may decide that for water supply certainty, it is better to resolve the disputes now than to agree to a short-term solution for a problem that is likely to occur again and again.[93] For much larger deficits, more than 1 MAF, there could be controversy within the Upper Division States. If Wyoming officials were to conclude that Colorado had used more than its apportionment during the preceding ten years, it may object to the use of Flaming Gorge Reservoir water to help erase the deficit. Recreation on Flaming Gorge is a major economic driver in Southwestern Wyoming. The state certainly would be under considerable political pressure from local officials to do so.

The second basic approach would be for the UCRC to formally declare and distribute a curtailment of sufficient quantity to bring the ten-year flow at Lee Ferry up to 82.5 MAF by the end of the water year. Based on comments by Upper Division State officials, this approach is the most unlikely option to be considered.[94] Upper Division State officials have been very successful in pointing to structural overuse in the Lower Basin as the primary problem in the basin. The combination of switching messaging and implementing a curtailment that would certainly have economic and perhaps even public safety impacts within one or more of the Upper Division States would be a political nightmare. Such a move would be seen as a “surrender” to the Lower Basin and would lock in the inequities of the 1922 Compact.

The third basic approach would be for the UCRC to either do nothing or to formally conclude that even though the ten-year Lee Ferry flow has fallen below 82.5 MAF, the Upper Division States are still in full compliance with Article III of the 1922 Compact. This approach would put the burden on the Lower Division States to legally challenge the UCRC’s decision or non-decision. There are several different litigation paths: one or more of the Lower Division States could file a complaint in the U.S. Supreme Court claiming that the Upper Division States are violating Article III of the 1922 Compact; Arizona as a signatory of the Upper Basin Compact could sue the UCRC and the four Upper Division States for violating the Upper Basin Compact; one or more of the Lower Division States and their water agencies could sue the Secretary of the Interior in federal district court for violating Section 602 of the 1968 Colorado River Basin Project Act;[95] or, under the theory of “throw everything at the wall and see what sticks,” all of these alternatives could be taken, in addition to others not identified in this article.

An approach that triggers litigation is the one that has the highest chance of imposing a curtailment on the Upper Division States that would impact water uses within Colorado. The interstate litigation process would likely take a decade or more to resolve; however, it is also possible that the Lower Basin States could ask the court, or its Special Master, for an injunction for immediate relief.[96] Depending on water supply conditions and the size of the curtailment, this could result in an order directing the UCRC to make up the compact deficit by implementing a curtailment or by releasing available stored water (or both).

The fourth approach would be a negotiated settlement of the disputed 1922 Compact issues among all seven Basin States, essentially a major re-write of the Compact. Whether all States would agree to begin negotiations before litigation is an open question. If a suit is filed in the Supreme Court, it is likely that the court or its Special Master would strongly encourage the States to attempt a negotiated settlement. The 1922 Compact includes a dispute resolution provision, Article VI.[97] It only requires the governor of one of the affected states to initiate the process.[98] Article VI has never been formally used, perhaps because any proposed settlement requires ratification by the legislatures of the affected states. In recent years, the Basin States have turned to congressional legislation to implement basin-wide agreements.[99]

If the Lee Ferry ten-year flow approaches or drops below 82.5 MAF, the basin will face a defining moment that has been labeled the compact’s first “hydrologic trip wire.”[100] It is an event that will not sneak up on or surprise anyone or any agency in the basin that is involved in the use and management of the river. There should be no excuse for any state or agency not to be prepared for this possibility. The initial move will be up to the Upper Division States acting through the UCRC. Publicly, Upper Division State officials have expressed little concern over the potential for a curtailment,[101] but when faced with the decision to do something or nothing as Lee Ferry flows approach the tripwire, the UCRC might become more conservative. The consequences of every approach could have significant impacts on each of the UD States.[102]

V. Potential Consequences of a Curtailment for the State of Colorado

As the most populous and largest consumer of Colorado River water among the Upper Division States, Colorado is at an elevated risk of being impacted by a Colorado River curtailment. While the probability of a curtailment may be low, it is an event with very large consequences.

Based on the provisional Consumptive Uses and Losses Reports and the Phase IV Risk Study modeling conducted by Hydros Consulting, Colorado is consumptively using about 2.3 MAF per year of Colorado River water, not counting its share of evaporation on Lake Powell, Flaming Gorge, and the Aspinall Unit.[103] The following is a summary of Colorado’s Colorado River water use:

| Table 1 Consumptive Use Summary | |

| Provisional Consumptive Uses and Losses Reports[104] | |

| Average Consumptive Use (2011-2020) | 2.25 MAF/year |

| Percentage of the Upper Division State Total (2011-2020) | 55.1% |

| Average Exports/Transmountain Diversions (2011-2020) | 0.497 MAF/year |

| Average In-Basin Agricultural Use (2011-2020) | 1.53 MAF/year |

| Hydros Modeling Results (2020 demand level)[105] | |

| Average Consumptive Use | 2.37 MAF/year |

| Average Pre-Compact Consumptive Use | 1.30 MAF/year |

| Average Post-Compact Consumptive Use | 1.07 MAF/year |

| Average Pre-Compact Export/TMD Use | 0.019 MAF/year |

| Average Post-Compact Export/TMD Use | 0.520 MAF/year |

| Percentage of Export/TMD Use Post-Compact | 96.5% |

| Percentage of West Slope Use Post-Compact | 27.6% |

An analysis of these data suggests several important conclusions:

- There is good agreement between the modeling results, which are based on Colorado’s StateMod platform, and the consumptive uses and losses data prepared by the Bureau of Reclamation primarily based on gage and field data.

- Colorado’s current use of 55.1 percent of the total Upper Division State use exceeds its Upper Basin Compact apportionment (51.75 percent) by approximately 3.3 percent; thus, if the UCRC were to declare a curtailment in the future and the proportionate uses by the Upper Division States was the same as today, Colorado would be at risk of being in an overuse situation under Article IV(b) of the Upper Basin Compact. Two important qualifications are (1) the consumptive uses and losses data are provisional and are currently being revised, and (2), the UCRC has not published formal rules and regulations for determining that a state has overused its apportionment.

- Transmountain diversions, also referred to as exports, make up approximately twenty-two percent of Colorado’s total consumptive use, but make up approximately fifty percent of Colorado’s post-compact consumptive uses.

- Colorado’s transmountain diversions are primarily post-compact uses (96.5 percent), whereas Western Slope uses are primarily pre-compact (72.4 percent). Although only 27.6 percent of West Slope water uses are post-compact, many of the critical water supply reservoirs that are used to meet late summer, fall, and winter irrigation and municipal demands are post-compact.[106]

- The definition of pre-compact rights is a critical assumption. The Hydros modeling assumes that rights perfected before June 25, 1929, are pre-compact and that these pre-compact rights are not restricted to delivering the amount of water that was being delivered in 1929. These are study assumptions; the State of Colorado has never issued rules and regulations that define when a water right is considered a pre-compact right under the 1922 and Upper Basin Compacts.

The obvious conclusion from the currently available data and published model results is that if the UCRC were to find, or was compelled by a court to find, that a curtailment is necessary to be in full compliance with the 1922 Compact, Colorado’s post-compact uses would be at considerable risk of curtailment. If the amount of the curtailment needed is 1 MAF or more, because of Colorado’s overuse situation, potentially, all post-compact uses might have to be shut off to meet the UCRC curtailment order.[107] However, as discussed below, the reality in a theoretical compact curtailment situation might be much different. Due to the economic, safety, and political importance of post-compact water rights, a concerted effort by the owners and operators of those rights to use or sacrifice West Slope pre-compact water rights could allow some portion of the post-compact rights to continue consuming water.

Because Colorado has not issued rules and regulations governing how the State Engineer would administer a Colorado River compact curtailment, analyzing the impacts of such a curtailment necessarily involves considerable speculation. Describing the impacts of a curtailment that is large enough to shutoff all post-compact uses may be the most straight forward. Assuming the UCRC set the timing of the curtailment as April 1 through the end of the water year, September 30—the period when reservoirs are being filled and fields and lawns are being irrigated—a curtailment would prevent the annual filling of all post-compact reservoirs and diversions by all post-compact direct flow consumptive rights. How the State Engineer would deal with post-compact reservoir water that was stored in previous years is one of many unresolved questions.

I believe the impacts to Colorado of this curtailment scenario would be very significant. Municipal water supplies throughout Western Colorado and the Front Range would be impacted. To maintain human health and safety, many communities would have to obtain emergency water supplies. The impacts would extend beyond municipal providers, many West Slope irrigation systems that use pre-compact direct flow rights rely on post-compact reservoir releases for late season water supplies. It is possible that the Colorado Governor would be called on to declare a state of emergency.

The impacts of a curtailment would go well beyond consumptive uses. Because a curtailment would require Colorado to deliver additional water to Lee Ferry, impacts to instream flows and in-stream recreation are difficult to assess, but there clearly would be major impacts to reservoir-based recreation. There could also be impacts to industrial uses on the West Slope, but except for the thermal-electric power plants in the Yampa Valley,[108] consumptive uses on the West Slope for industrial purposes are relatively small.

VI. Unique Issues Related to the Impacts of a Curtailment on Transmountain Diversions

The diversion of water from the Colorado River Basin to the East Slope is an issue that has politically divided the State of Colorado for well over a century.[109] The first transmountain diversions were planned and developed in the late 1800s.[110] These first systems were relatively small, simple, and non-controversial.[111] By the early 1930s, however, in response to the 1930s drought and the over-appropriation of the native water available for use in the Arkansas and South Platte River Basins, East Slope water providers pursued the development of much larger projects that would have a very significant environmental and water supply impacts on the West Slope.[112] These larger projects were of the scale that required either financial support from the federal government or the backing of a large municipality such as Denver.[113]

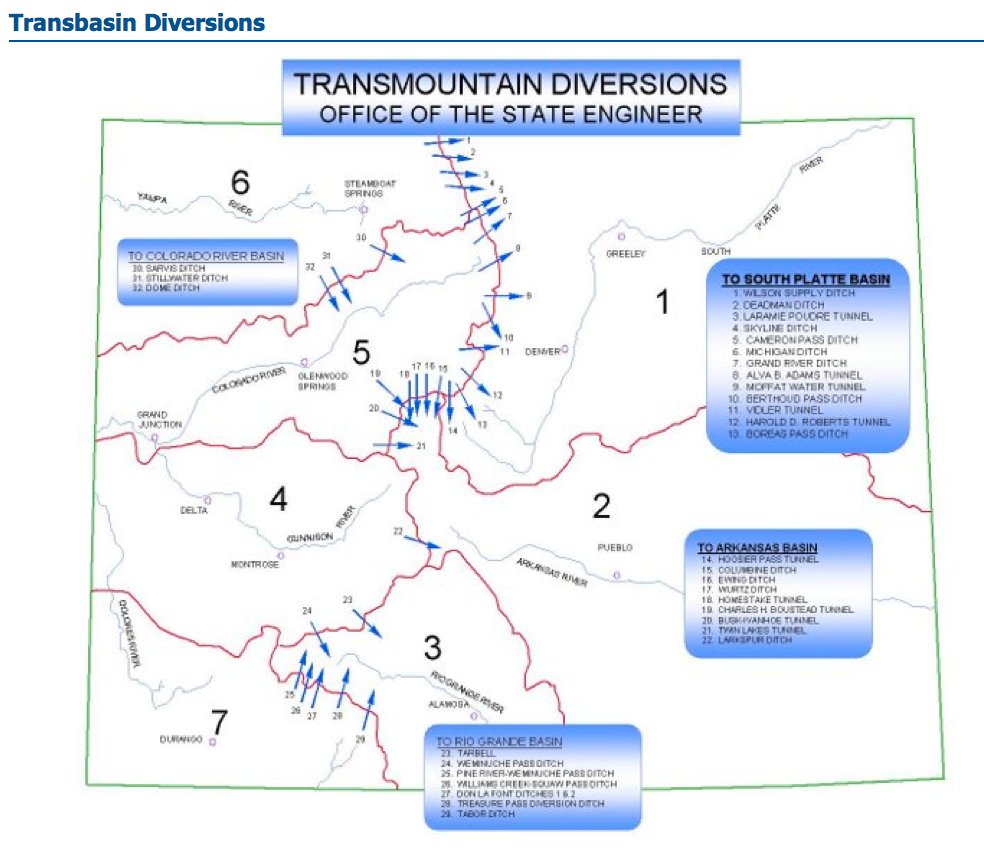

Today, seven major transmountain diversion systems and a handful of mid-sized projects (they might be referred to as “mid-majors”) divert an average of over 500,000 acre-feet per year to the East Slope. The major transmountain projects from north to south are:

The Colorado-Big Thompson Project (“C-BT”) was built by the Bureau of Reclamation from the late 1930s through the 1950s. The project diverts water from the headwaters of the Colorado River in Grand County for delivery to Northern Front Range users in the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District service area. West Slope features of the project include the 100,000 acre-feet pool in Green Mountain Reservoir. Although originally designed as a supplemental irrigation project, today approximately seventy-five percent of the project shares are owned by municipal and industrial users. Unlike most other transmountain diversion projects, C-BT shareholders can only make one use of the imported water.[114] C-BT return flows are dedicated to the South Platte River and cannot be fully reused.

The Windy Gap Project is a non-federal project that pumps water from the Colorado River near Granby and then uses the C-BT Project to deliver the water to Northern Front Range cities. The project was built in the 1980s and is operated by the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District Municipal Subdistrict. The Windy Gap Firming Project, currently under construction, will divert additional Colorado River and increase the Windy Gap Project’s reliable yield.[115]

The Moffat Tunnel Collection System was built by the City of Denver in the 1930s. It diverts water from the Fraser River and Williams Fork River basins for delivery through the Moffat Railroad Tunnel pilot bore to the East Slope for use in the Denver Water service area. Because of past agreements between Denver and downstream irrigators on the South Platte River, only the junior portion of Denver’s Moffat System diversions are fully reusable. Denver’s Gross Reservoir expansion project, currently under construction, will increase its average annual diversions from the Fraser and Williams Fork Rivers.[116]

The Dillon Reservoir-Roberts Tunnel Collection System was built by the City of Denver in the 1950s and 1960s. Project water is delivered from the Blue River to the South Platte River for use in the Denver Service area. The project is upstream of and junior to Green Mountain Reservoir, a feature of the C-BT project.[117]

The Homestake Project, built in the 1970s, diverts water from the headwaters of the Eagle River. The cities Aurora and Colorado Springs are co-equal owners of the Project.[118]

The Fryingpan-Arkansas Project was built by the Bureau of Reclamation in the 1960s and 1970s. It diverts water from headwaters of the Fryingpan River into the Arkansas River Basin for use in the Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District service area. Approximately fifty percent of the water diverted is used for municipal purposes, including by the cities of Colorado Springs and Pueblo.[119]

The Independence Pass Transmountain Diversion Project diverts water out of the Roaring Fork River headwaters into the Arkansas River Basin. The Project was built by the Twin Lakes Reservoir and Canal Company in the 1930s. The Project received federal financial assistance from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. Originally built to provide supplemental irrigation water for the lands served by the Colorado Canal, today, all but a small fraction of the project yield is used by the cities of Colorado Springs, Pueblo, Pueblo West, and Aurora.[120]

In addition to these major projects, there are a handful of medium-sized diversions (the mid-majors) and a dozen or so smaller transmountain diversions.[121] This list includes the Grand River Ditch system operated by the Water Supply and Storage Company, which diverts water from the Colorado River in Rocky Mountain National Park. Originally a supplemental irrigation supply for the South Platte River, today the cities of Fort Collins and Thornton own most of the project shares. Project construction began in 1890 but wasn’t completed until 1934. A portion of the project’s water rights are pre-compact. Thornton has not yet built a conveyance project to deliver Company water from the Fort Collins area to its system.[122]

Collectively, transmountain diversion projects divert an average of about 500,000 acre-feet per year to the East Slope but the amount varies annually based on local water availability and demands. About 120,000 acre-feet is diverted to the Arkansas River Basin with the remainder going to the South Platte River Basin. Roughly half of the exported water is fully reusable, but because of infrastructure and exchange limitations, not all reusable water can physically be reused. A large majority of the transmountain water diverted across the Continental Divide may be owned or used by municipal and industrial users, but in wetter years, surplus transmountain water is leased on a temporary basis to agricultural users.[123] As noted above, there are projects currently under construction that will increase the capacity of existing projects to export water. Modeling suggests that in the future, the annual average could go up to about 600,000 acre-feet per year.[124]

Map of Transmountain Diversions[125]

Map of Transmountain Diversions[125]

In response to efforts by the Northern Colorado Water Users Association to obtain Congressional authorization of the C-BT Project, Western Slope leaders created the West Slope Protective Association, the predecessor of the Colorado River Water Conservation District. At the urging of then-Congressman Edward Taylor, whose district included the West Slope, representatives from the East Slope and West Slope negotiated a compromise that cleared the path for Congressional approval of the project. This compromise was documented as the “Manner of Operation of Project Facilities and Auxiliary Features” section of Senate Document 80, 75th Congress, First Session, dated June 15, 1937.[126]

One of the issues of concern for the West Slope negotiators was the impact a project of this magnitude would have on other West Slope water users in the face of a compact shortage. Paragraph (i) of the Manner of Operation Section states:

Inasmuch as the State of Colorado has ratified the Colorado River Compact, and inasmuch as the construction of this project is to be undertaken by the United States, the project, its operation, maintenance and use must be subject to the provisions of said Colorado River Compact of November 24, 1922 (42 stat 171) and of Section 13 of the Boulder Canyon Project Act, dated December 21, 1928 (45 Stat. 1057-1064). Notwithstanding the relative priorities specified in paragraph (g) herein, if an obligation of is created under said compact to augment the supply of water from the State of Colorado to satisfy the provisions of said compact, the diversion for the benefit of the eastern slope shall be discontinued in advance of any western slope appropriations.[127]

Subsequently, the manner of operation section was incorporated, verbatim, into the water rights for the Colorado-Big Thompson Project that were adjudicated in what is referred to as the “consolidated cases” or the “Blue River decrees,” and by reference into the 1956 Colorado River Storage Project Act.[128]

Unfortunately for Western Colorado, its leaders did not insist on similar provisions for the water rights adjudicated for the Independence Pass Collection system or Denver’s Moffat Tunnel Collection System. Perhaps, because they were smaller projects, or, in the case of the Moffat Tunnel Collection system, because of a prevalent attitude at the time was “what is good for Denver, our capital city, is good for the West Slope.”[129]

In 1943, West Slope leaders were successful at including area-of-origin protective language into Colorado’s water conservancy district statute. It was patterned after the Senate Document 80 compromise. The Act states:

Any works or facilities planned and designed for the exportation of water from the natural basin of the Colorado River and its tributaries in Colorado, by any district created under this article, shall be subject to the provisions of the Colorado River compact and the “Boulder Canyon Project Act.” Any such works or facilities shall be designed, constructed, and operated in such manner that the present appropriations of water, and in addition thereto prospective uses of water for irrigation and other beneficial consumptive use purposes, including consumptive uses for domestic, mining, and industrial purposes, within the natural basin of the Colorado River in the State of Colorado, from which water is exported, will not be impaired nor increased in cost at the expense of the water users within the natural basin. The facilities and other means for the accomplishment of said purpose shall be incorporated in and made a part of any project plans for the exportation of water from said natural basin in Colorado.[130]

How the State Engineer or a Water Court facing a Colorado River curtailment would interpret this provision is an open question. West Slope water users could argue that to avoid “impairment” of West Slope rights, the State must first curtail transmountain diversion projects covered by the Act. Only three of the major transmountain diversions—the C-BT Project, the Windy Gap Project, and the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project—are covered by this statute, yet these diversions represent approximately sixty percent of the total transmountain diversions, about 300,000 acre-feet per year.

The conservancy district statute also includes a provision prohibiting the conservancy districts that operate these projects from using their power of eminent domain to condemn West Slope water rights and divert the condemned water to the East Slope. This provision may be valuable in protecting pre-compact West Slope agricultural uses under curtailment conditions.[131]

The conservancy district statutes do not cover Denver’s transmountain diversion water supplies. Yet, a provision in the Blue River decree requires that to meet the requirements of the 1922 Compact, diversions by Denver from the Blue River must be shutoff or curtailed before diversions by the C-BT project are shutoff or curtailed.[132] This provision reflects the senior priority status of the C-BT, including the project’s Green Mountain Reservoir.

The language of Paragraph (i) of the Manner of Operation Section of Senate Document 80 became a matter of dispute between the River District and the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District during the Congressional debate over the 1968 Colorado River Basin Project Act. The West Slope sought Congressional authorization for five additional Reclamation Projects: The Animas-La Plata, Dolores, San Miguel, Dallas Creek, and West Divide Projects. To obtain the support of the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, the River District agreed to a limited reading of the language in Senate Document 80. The reading restricted the term “any Western Slope appropriation” to mean “the appropriation heretofore made for the storage of Green Mountain Reservoir,” instead of all West Slope appropriations.[133] A reasonable question can be posed as to whether the quid-pro-quo was worth it for the West Slope. Of the five projects authorized by the 1968 Act, only two, the Dolores and Dallas Creek Projects, were built as Reclamation projects.

The 1968 Act triggered an internal debate within Colorado over the impacts of a curtailment.[134] It requires projects within Colorado, constructed under the authority of the 1968 and 1956 Acts, to be administered based on priority. See Section 501(e):

In the diversion and storage of water for any project or any parts thereof constructed under the authority of this Act or the Colorado River Storage Act within and for the benefit of the State of Colorado only, the Secretary is directed to comply with the constitution and statutes of the State of Colorado relating to priority of appropriation; with State and Federal court decrees entered pursuant thereto; and with operating principles, if any, adopted by the Secretary and approved by the State of Colorado.[135]

VII. The Impacts to Colorado of a Curtailment of Transmountain Diversions

A curtailment that significantly reduces or eliminates the 500,000 acre-feet per year of transmountain diversions from the Colorado River Basin to the East Slope would have a profound negative impact on Colorado. These diversions are a critical source of water for most of the Front Range, where approximately eighty-five percent of Colorado’s population resides.[136] Major cities such as Colorado Springs and Denver rely on Colorado River water for fifty percent or more of their annual supplies. Some Northern Front Range Cities may be close to one hundred percent reliant on the imported Colorado River water.[137]

When the transmountain diversion projects were designed and built, there was little concern over the long-term reliability of these projects.[138] The potential that these projects would be curtailed to meet the 1922 Compact’s requirements was considered a far-off and unlikely possibility, if it was considered at all. Now, because of the impacts of climate change on the river’s flows, the threat is real. Modeling suggests that the hydrologic conditions that could result in a “compact tripwire” might happen within the next five to ten years.[139] Regardless of the answer to the various legal questions discussed above, an approaching tripwire could push Colorado water users and planners to take action. Modeling results also show that the expansion of transmountain diversions may represent seventy percent of Colorado’s additional use of Colorado River water.[140] This additional use of water increases the compact risk to all post-compact uses within the state.[141]

Western Slope water users fully understand that the curtailment of transmountain diversions would create additional problems for uses within the basin. These uses would go far beyond and amplify the curtailment of Western Slope post-compact rights. Concerns about East Slope communities that rely on the Colorado River have been raised for over ninety years, first raised during the negotiations over the authorization of the C-BT Project. Such concerns include facing a water supply emergency, East Slope communities that rely on Colorado River water would turn to the dry-up of Western Slope pre-compact uses, trampling its agricultural, environmental, and recreational-based economy in the process.[142]

If the threat of a curtailment was only a “black swan” event, occurring in 2028 or 2029 and then not occurring again for another fifty to sixty years, it might be manageable. The river modeling coupled with the best climate science, however, suggests this is not the case. A few wet years might temporarily improve conditions, but it is almost a certainty that another drought period, similar to or perhaps drier than 2000–2004 or 2020–2023 will happen again in the future. In that case, the Basin will be in another situation where storage levels are critically low and the ten-year cumulative flow approaches or falls below 82.5 MAF.

In response to a curtailment or even a serious threat of a curtailment, both East Slope and West Slope municipalities that utilize post-compact Colorado River water rights would carefully evaluate and take actions to improve the reliability of their water portfolios. Water supplies critical to health and safety simply cannot be shut off. The assumed solution would be: (1) to acquire pre-compact agricultural rights, and (2) to file for a change of water right and transfer the consumptive use to their diversion points. The critical municipal and industrial consumptive uses associated with post-compact transmountain diversions are an order of magnitude (ten to fifteen times) higher than post-compact municipal uses on the West Slope.[143] So the bulk of the impacts to pre-Compact West Slope agriculture would be attributable to the demands for compact security by junior transmountain diversions.

Additionally, the major transmountain diversions are almost all located in the upper reaches of the Colorado River above Glenwood Springs (primarily in Grand, Summit, Eagle, and Pitkin Counties). The process of transferring large amounts of consumptive use to diversion points located high in the headwaters would be contentious, complicated, expensive, and could take years to work out the details. There are likely many physical limitations and conflicts. Thus, it is possible that it will be easier and more reliable for many East Slope entities to turn to East Slope agricultural sources. Therefore, a Colorado River curtailment therefore has the potential to have statewide impacts on agricultural uses.

The threat of a curtailment or “compact call” is both real and serious. But, because of the many unresolved and disputed issues related to the interpretation of the 1922 Compact, and the ongoing negotiations among the states for the post-2026 operating rules, it is not a foregone conclusion.

In 1986, when Carlson and Bowles wrote “Contrary Views” they were concerned Colorado’s share of the 5.3 to 5.8 MAF per year that they believed was available to the Upper Basin under the 1922 Compact [144] (the “leftovers”) was not enough to meet the State’s future needs. They explored various legal and political strategies that Colorado and its fellow Upper Division States could use to correct the inequities in the 1922 Compact and the Law of the River. What they could not foresee was that in a little more than a decade, the Upper Basin would plunge into a prolonged drought, worsened by impacts of anthropogenic climate change on the hydrology of the Colorado River.[145] Assuming a continuation of the 12.5 MAF per year average natural flow at Lee Ferry seen since 2000, the “compact leftovers” are now far less than the amounts assumed by Carlson and Bowles. If the provisions of Articles III of the 1922 Compact are interpreted wholly against the Upper Division States, the amount of water available for use in the Upper Basin, the “leftovers,” could be as low as 3.5 to 4.2 MAF per year. This is less than what the Upper Division States are currently consuming![146]

The combination of climate change reducing the leftovers available to the Upper Basin and a compact written over a century ago that could impose fixed flow obligations on the Upper Division States is a recipe for a disaster. That disaster would hit Colorado in the form of a compact curtailment, a “compact call.” So far, Colorado and its fellow Upper Division States have avoided this problem. Consistent with the intended purpose of the 1956 Act, the Upper Basin has relied on the release of water stored in Lake Powell from previous decades to maintain ten-year flows above the 82.5 MAF, the first compact “tripwire.” The system math, however, will not allow this strategy to continue. The available storage is being depleted. Modelling suggests that there is a high chance that within the decade, perhaps as early as 2027, flows will drop below this threshold. At this point, the Colorado River Basin would face a governance crisis. The result of which would likely be either a short-term agreement that temporarily puts off the issue or litigation. Under the litigation scenario, it is possible but not a certainty, that either the U.S. Supreme Court or its Special Master would impose a curtailment on the Upper Division States.[147]

A Colorado River curtailment is a subject that has received little analysis or study by academics or water agencies. In their papers, both Getches and Carlson and Bowles make no mention of the potential impacts of a curtailment of existing uses. The 2012 Colorado River Basin Study jointly sponsored by Reclamation and the basin states carefully avoided the subject. It was considered “too hot to touch.”[148] The 2023 Colorado Water Plan Update does not address the impacts of a curtailment on the State. Curtailment is not even listed as one of the threats facing water use in Colorado. The plan’s only mention of a curtailment is in a sidebar describing the conceptual framework for the development of new transmountain diversions.[149] The River District and Southwestern Water Conservation District were the first agencies to begin modelling and publicly discussing the risks associated with a 1922 Compact curtailment with the “Risk Study” series that began in 2014.[150]

Colorado’s economic vitality relies on the use of post-compact water rights, including the diversion of 500,000 acre-feet of Colorado River water to the East Slope, primarily for use by Front Range cities. A curtailment of these rights would have statewide impacts and require statewide solutions.

State of Colorado water officials are clearly caught between the proverbial “rock and a hard place.” Publicly they express confidence that Colorado and the other Upper Division States are in full compliance with the 1922 Compact and that there is little to no risk of a future curtailment.[151] To do so, I believe that they have had to make new, novel, and untested theories and interpretations of the 1922 Compact and the Upper Basin Compact. Theories and interpretations that may be inconsistent with the views and writings of their predecessors like Clifford Stone and Jean Breitenstein[152] and Compact scholars like Special Master Simon Rifkind, Charles Meyers, Davis Getches, and John Carlson. My concern is that maintaining the position, based on these new, novel, and untested theories, that there is only a minuscule risk of a future compact curtailment comes with the risk that the State will not be fully prepared for a potential curtailment.