Introduction

A tension exists that must be reconciled between Colorado’s management of its natural resources and its stated commitment to fighting climate change. The Colorado executive and legislative branches have, through laws, public statements, and plans, indicated their dedication to fighting climate change. In the 2019 regular session, the Colorado legislature enacted several bills directed toward combating climate change. For example, the Climate Action Plan to Reduce Pollution Act (“SB 19-1261”) sets climate targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by twenty-six percent by 2025, fifty percent by 2030, and ninety percent by 2050 from 2005 levels.[2] In the same session, the legislature overhauled its regulation of the oil and gas industry with the Protect Public Welfare Oil and Gas Operations Act (“SB 19-181”), which altered the mission statement of the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (“COGCC” or the “Commission”) and subjected the industry to more stringent regulations.[3] In January of 2021, Governor Jared Polis issued a Greenhouse Gas Pollution Roadmap, which aims to implement the SB 19-1261 climate targets.[4] Following the passage of an additional bill outlining targets directed specifically at the oil and gas sector in December of 2021,[5] the Colorado Air Quality Control Commission (“AQCC”) issued new regulations focused on the oil and gas sector. The regulations target a thirty-six percent reduction from the 2005 baseline by 2025 and a sixty percent reduction by 2030, mostly by mitigating methane leaks through more frequent and thorough well and facility inspections.[6] Finally, in the 2023 Regular Session, the Colorado General Assembly changed the name of the COGCC to the Energy and Carbon Management Commission (“ECMC” or the “Commission”) and gave the commission a hard deadline to promulgate rules to evaluate and address cumulative impacts of oil and gas development.[7]

However, absent within these plans, statutes, and regulations is a substantial recognition of Colorado’s role in producing and exporting oil and natural gas. The Air Pollution Control Division (“APCD”) reports that oil and gas production was the fourth largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Colorado, contributing over sixteen percent of the total emissions.[8] In 2019, the combustion of Colorado-produced oil resulted in 75.6 million metric tons of carbon dioxide.[9] That same year, Colorado produced enough natural gas to result in 108.7 million metric tons of carbon dioxide.[10] While Colorado exports a significant majority of its produced natural gas and most of its oil, Colorado does not yet require out-of-state combustion of Colorado-produced oil and gas to be counted as statewide emissions for the purposes of SB 19-1261.[11] This indicates that Colorado can potentially reach its climate targets without having to account for its substantial contribution to greenhouse gas emissions through its export of oil and gas.

Nevertheless, the Commission continues to permit oil and gas wells and development at a rapid rate. It has approved the creation of close to 5,000 wells since passing SB 19-181. The Colorado State Land Board, which owns 2.8 million acres of surface land and four million acres of mineral estate, continues to lease Colorado state-owned land for oil and gas exploration and production.[12] Production forecasts anticipate that Colorado will increase its oil production from the 2005 baseline by seventy-five percent by 2030 and increase gas production by thirty-three percent in the same period.[13]

Importantly, there is a significant gap between current and planned extraction by oil and gas operators and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s figure for the remaining global “carbon budget” (the total amount of remaining greenhouse gas emissions that scientists believe we can release to the atmosphere while maintaining some chance of avoiding global ecological catastrophe).[14] To rectify this gap, every fossil fuel producer must begin to ramp down the production of fossil fuels to stay within this planetary budget.[15] This reduction includes cutting natural gas and oil production, as oil contributes a third and natural gas contributes a fifth of the world’s carbon emissions.[16]

The Commission, as the primary regulator of oil and gas operations within the state, has a responsibility to participate in this global effort to ramp down the use of and reliance on fossil fuels. While Colorado has numerous environmental regulations targeting the air, land, and water in Colorado, it continues to approve new wells at a rapid rate. These approvals continue without directly considering or addressing all the ways in which Colorado contributes to climate change.[17] Furthermore, no current Commission rule directly indicates that the agency can delay, deny, or limit the permitting of oil and gas to help meet Colorado’s greenhouse gas targets.

Environmental advocates have examined and utilized legal tools to reduce and terminate fossil fuel production, particularly by petitioning the federal government to terminate existing or future oil and gas leases.[18] An article, written by Eric Biber and Jordan Diamond titled, “Keeping it All in the Ground?,” explored the legal bases for terminating existing and future oil and gas leases on federal public land.[19] In particular, it focused on whether Congress could pass legislation terminating existing fossil fuel leases on public land and whether the President and the Department of the Interior could terminate leases by executive order.[20] The article concluded that both Congress and the Executive branch have the power to terminate leases because of climate impacts based on inherent congressional authority, the Department of the Interior’s power to implement public lands law, and the Supreme Court’s recognition of the power of the executive branch to manage government contracts.[21]

This Note undertakes a similar analysis to that of Biber and Diamond’s article by assessing the validity and likelihood of success of various legal strategies for reducing the production and export of oil and gas in Colorado. Specifically, it analyzes whether a lawsuit could force the Commission to engage in rulemaking that severely limits or ends oil and gas production in Colorado under existing law or the Colorado Constitution.

This Note seeks to answer this question by first briefly discussing Colorado’s oil and gas geology and the existing legal framework. Second, it will evaluate previous legal actions aimed at keeping oil and gas in the ground. Third, it discusses how Colorado has amended its oil and gas law in ways that have helped, or could be used to, limit oil and gas production. Fourth, this Note assesses the extent to which these amendments have actually served to keep oil and gas in the ground in the years following SB 19-181’s enactment. Finally, having established the framework of Colorado oil and gas law, this Note explores the legal bases for keeping oil and gas in the ground. This includes a discussion of a possible legal challenges to a Commission’s eventual rulemaking requiring it to consider cumulative and adverse impacts and environmental protections that exist within the Colorado Constitution.

I. An Overview of Colorado Oil and Gas and Its Historical Approach to Regulation

An understanding of recent and future changes to Colorado’s oil and gas law requires placing it within a historical and geologic context. This context requires an explanation of Colorado’s geology and its historical approach to regulating oil and gas. It also necessitates a discussion of how Colorado courts have treated challenges aimed at keeping oil and gas in the ground.

A. Colorado’s Geology

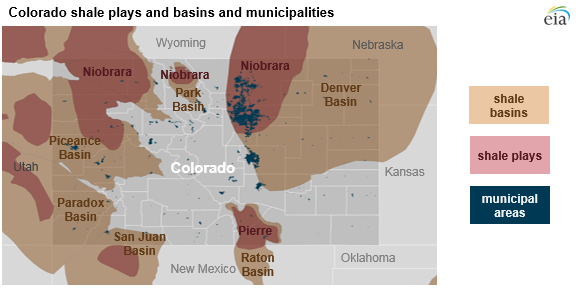

Colorado’s geology makes it a significant player in oil and gas production. Because of its location on top of the Denver Basin and the Niobrara Shale, Colorado has eleven of the country’s largest natural gas fields and three of its largest oil fields.[22] In 2022, Colorado stood as the fifth largest oil-producing and eighth largest gas-producing state in the country.[23] Furthermore, Colorado produced 3.5 percent of the country’s total crude oil and almost five percent of the country’s total natural gas.[24] While it is uncertain how much oil and gas production in Colorado contributes to total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, it is clear that Colorado plays a significant role in total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.[25]

Most of Colorado’s oil and gas development exists within the Denver-Julesburg Basin, which extends from the front range of Colorado to Nebraska and Wyoming.[26] Colorado has the potential for significantly more production, as some experts have compared the Niobrara Shale to the successful Bakken Shale formation in North Dakota, Montana, and Saskatchewan, which has consistently produced around 1.2 million barrels of crude oil a day.[27] Additionally, the Western Slope of Colorado has substantial deposits of natural gas.[28] However, the prevalence of federal public lands in this region has made the approval process for new wells more  costly and has somewhat limited its development.[29]

costly and has somewhat limited its development.[29]

Figure 1[30]

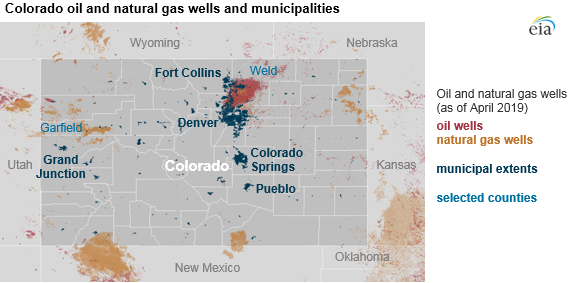

This geology has led to the development of a significant oil and gas industry and infrastructure in the state. Oil and gas were first produced commercially in 1862 and production has continued uninterrupted to the present day.[31] By 2019, production reached almost two trillion cubic feet of natural gas and over two hundred million barrels of oil.[32] This production means that Colorado produces significantly more oil and gas than it consumes, exporting around two-thirds of its natural gas and most of its oil to other states.[33]

Figure 2[34]

Figure 2[34]

B. Colorado’s Historic Approach to Regulation of the Production of Oil and Gas

Historically, Colorado’s regulation of oil and gas dealt exclusively with problems associated with inefficient production and inequitable outcomes for owners of oil and gas interests. However, through a series of legislative reforms starting in the 1990s, Colorado began to assume the role of an environmental regulator.

Prior to Colorado’s efforts to regulate oil and gas, the common law “rule of capture” allowed oil and gas producers to take title to all the oil and gas they could extract, regardless of whether that oil or gas migrated from adjoining lands.[35] This rule created a tragedy of the commons, or a situation in which a group, acting in their own self interests in the short-term, depletes a common resource, undermining the entire group’s long-term interests.[36] Here, property owners were incentivized to drill as quickly and as densely as possible to prevent the forfeiture of property through the drainage of a shared reservoir.[37] This process resulted in excessive development of drilling infrastructure and injury to other property owners by stranding oil and gas resources underground.[38] Excessive drilling caused pressure, which allowed producers to draw oil and gas to the surface, to dissipate, stranding a significant portion of the resources underground.[39] The rule of capture created the additional problem of incentivizing rapid drilling before operators could develop the infrastructure used to transport and refine the oil and gas.[40] Because oil producers could not often economically or effectively capture natural gas that was released as a byproduct of oil drilling, producers would flare (burn) or vent the natural gas into the atmosphere, wasting resources and reducing the pressure in the reservoir.[41]

The problems associated with the rule of capture likely necessitated the creation of a regulatory body to manage oil and gas production.[42] Created by law in 1951, the Colorado legislature originally tasked the Commission with three basic functions: (1) to minimize waste, (2) to protect the correlative rights of property owners, and (3) to promote efficient production.[43] The Colorado legislature traditionally defined “waste” as the spillage of oil and gas or the stranding of oil and gas underground through the dissipation of reservoir energy.[44] The definition also included the venting of natural gas into the open air.[45] To minimize waste, the Colorado legislature empowered the Commission to regulate the siting and density of drilling units. It also authorized the Commission to require owners to plug wells to prevent the release of gas into the atmosphere.[46]

As waste within the common pool jeopardizes the correlative rights of other owners by limiting the amount of oil and gas that can be produced, the Colorado legislature authorized the Commission to force the pooling of various property interests in a commonly shared reservoir.[47] Under this scheme, which largely exists today, producers of oil and gas were forced to pay a royalty to owners with a property interest in the common reservoir, allowing for the equitable division of profits from the depletion of the shared resource.[48] The pooling of resources could be done voluntarily through contractual negotiations between producers and other owners or through an administrative hearing process, called “forced pooling.”[49] In the absence of voluntary pooling, “an interested party” could file an application with the Commission and begin the process of forced pooling.[50] If an owner of the shared reservoir did not consent to drilling of oil and gas in the shared pool, the Commission would force the non-consenting owner into the pool and require them to accept 12.5 percent of the proportionate proceeds until 200 percent of the non-consenting owners’ share of the drilling costs and 100 percent of their share of the surface costs were paid off.[51]

Through this administrative scheme, the Commission prevented individual hold out while still ensuring the correlative rights of various owners through royalties. The forced pooling mechanism provided a powerful tool for oil and gas producers to circumvent non-consenting owners and accelerate the pace of oil and gas development. Forced pooling demonstrates the extent to which Colorado emphasized efficient production and prioritized drilling over leaving oil and gas in the ground.

Colorado designed its oil and gas law and the Commission with economic efficiency in mind.[52] Prior to the passage of SB 19-181 in 2019, the Colorado legislature amended the Commission mission three times. Each time, it added language that encouraged the protection of health, safety, and the environment, but the emphasis remained on economic efficiency and encouraging production. The Colorado legislature amended the oil and gas law in 1979 and declared the original purpose of the Commission was to “foster, encourage, and promote the development, production, and utilization of the natural resources of oil and gas in the state of Colorado . . . .”[53] In 1994, the language, “in a manner consistent with protection of public health, safety, and welfare” was added to the Commission’s legislative purpose.[54] In 2007, the Colorado legislature added language requiring the Commission to “[p]lan and manage oil and gas operations in a manner that balances development with wildlife conservation.”[55] Despite these environmentally focused amendments to the Commission’s mission, nothing in these amendments acknowledged that production inherently endangered the public welfare or the environment.[56]

Additionally, to promote efficiency, Colorado’s laws and its Constitution have also permitted oil and gas pipeline companies to use the power of eminent domain to condemn private property for public use.[57] Furthermore, Colorado courts have held that the development of Colorado’s natural resources (specifically the building of natural gas pipelines) has been recognized as a public use for the purposes of eminent domain.[58]

C. Past Legal Challenges Aimed at Limiting Oil and Gas Production

Before the passage of SB 19-181, environmental activist groups and progressive municipalities found minimal success in attempting to curb the extraction of oil and gas. Two cases are particularly significant and illustrative of the way in which the Colorado Supreme Court has rejected efforts to keep oil and gas in the ground. In City of Longmont v. Colo. Oil & Gas Ass’n, the Colorado Supreme Court rejected the ability of counties and municipalities to regulate oil and gas within their jurisdiction.[59] In COGCC v. Martinez, the Colorado Supreme Court rejected efforts to require the Commission to address the cumulative effects of the oil and gas permitting decisions on climate change.[60]

In Longmont, an environmentally progressive municipality unsuccessfully attempted to defend the power of local governments to regulate and limit oil and gas development.[61] The City of Longmont had, by a public ballot initiative, banned hydraulic fracturing (fracking) within the city limits.[62] The Commission, the Colorado Oil and Gas Association, and a Colorado-based oil and gas company sued Longmont, arguing that local regulatory powers were preempted by state law.[63] The Supreme Court agreed, holding that the state’s interest in the efficient and fair development of oil and gas resources in the state required statewide uniformity of oil and gas regulation.[64] Therefore, local regulation of the industry and the banning of fracking would result in an incoherent patchwork, would waste oil and gas by making oil and gas extraction less efficient, and would negatively affect the correlative rights by intensifying production in some areas while minimizing production in others.[65]

In Martinez, respondents had proposed a rule preventing “the Commission from issuing any permits for the drilling of an oil and gas well ‘unless the best available science demonstrates, and an independent third-party organization confirms, that drilling can occur in a manner that does not cumulatively, with other actions, impair Colorado’s atmosphere, water, wildlife, and land resources, does not adversely impact human health, and does not contribute to climate change.’”[66] This proposed rulemaking was based on a version of the C.R.S. § 34-60-102(1) before it was amended by SB 19-181 in 2019, which stated that it was in the public interest to “[f]oster the responsible, balanced development, production, and utilization of the natural resources of oil and gas in the state of Colorado in a manner consistent with protection of public health, safety, and welfare, including protection of the environment and wildlife resources.”[67]

The Commission declined to engage in the rulemaking. The Colorado Court of Appeals published a decision holding that the Commission’s decision against the rulemaking was erroneous because the term “balanced” only modified “development” and not the other terms.[68] Therefore, the statute, as it existed in 2019, did not require a balancing test between development and environmental protection but rather the language—”in a manner consistent with”—indicated that environmental protection is a condition that must be fulfilled.[69]

The Colorado Supreme Court reversed the decision of Colorado Court of Appeals and rejected the petitioner’s request for a rulemaking for three reasons. First, it found that its review of an agency’s decision whether to engage in a rulemaking is highly deferential.[70] Second, the court held that the language of C.R.S. § 34-60-102(1) (2016) was ambiguous as to whether the statute required a balancing test between environmental protection and oil and gas development and whether the statute meant that environmental protection was a condition that must be fulfilled.[71] However, using various tools of statutory interpretation, including the legislative history, the court held that the statute was intended to balance both oil and gas development and environmental protection and thus the Commission was not required to implement the rule making.[72] Specifically, the language of C.R.S. § 34-160-106(2)(d)(2016), which directed the Commission to take “into consideration cost-effectiveness and technical feasibility,” meant that the law tolerated some possible environmental risk, rather than condition production on requiring that all adverse environmental impacts be mitigated.[73] Finally, it held that the Commission reasonably relied on the knowledge that it was working with the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment on the issue the proposed rule aimed to address.[74]

II. How Colorado has Updated its Laws and Regulations to Potentially Limit Oil and Gas Production

The passage of SB 19-181 reoriented the regulation of oil and gas law by explicitly prioritizing the protection of public safety, health, welfare, and the environment over efficient production, preventing economic waste, and protecting correlative rights.[75] Past challenges in the Colorado Supreme Court highlight the extent to which Colorado’s laws had prioritized the efficient development of oil and gas. In part, SB 19-181 aimed to correct these decisions by amending the law. To address the decision in Longmont, the bill altered the regulatory framework to empower local governments to regulate oil and gas.[76] In addressing the decision in Martinez, the bill changed a number of elements of the Commission mission and regulations.[77]

Much of SB 19-181 focuses not on limiting oil and gas production itself, but instead on regulating pollution in the state of Colorado that results from oil and gas production. Much of the bill abrogates the Commission’s exclusive regulatory jurisdiction over oil and gas production and directs the AQCC, the Water Quality Control Commission, the Colorado State Board of Health, and the Solid and Hazardous Waste Commission to regulate different aspects of the process.[78]

While additional oversight from more regulatory bodies may make oil and gas production more burdensome and costly, it does not directly aim to keep oil and gas in the ground. For example, Section 3 of SB 19-181 directs the AQCC and producers to continuously monitor and inspect facilities to avoid the leaking of methane from wells or pipelines.[79] While these regulations play an important role in controlling the localized and nationwide effect of methane emissions, they do not directly acknowledge that the burning of these fossil fuels results in greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change.

However, there are several provisions within SB 18-191 that could serve as mechanisms to keep oil and gas in the ground or could empower regulators and citizens to challenge new production. These provisions include alterations to the Commission’s mission and purpose, changes to the statutory definitions of “waste” and “adverse impacts,” mandates requiring the Commission to address cumulative impacts, empowerment of local authority with regulatory power, more stringent setback and Alternative Location Analysis requirements, and new pooling requirements.[80]

These alterations operate in a variety of ways to keep oil and gas in the ground. Some of these alterations, like the empowerment of local authorities and Alternative Location Analysis requirements, could functionally serve to keep oil and gas in the ground by increasing the regulatory burden, time, and money required to develop new production. Other alterations, including the empowerment of local authorities and the setback requirements, make siting of new production significantly more difficult and may limit the geographic spread of oil and gas in a substantial way. Finally, several important alterations, including the mission change, the new definitions of waste and adverse impacts, and the new mandates related to adverse and cumulative impacts, could keep oil and gas in the ground by forcing the Commission to prioritize the environment and potentially acknowledge the industry’s effect on climate change.

A. Amendments to the Commission’s Mission

SB 18-191 altered the language of the mission statement that the court relied on in Martinez. The original language of C.R.S. § 34-60-102(1) stated that it was in the public interest to “[f]oster the responsible, balanced development, production, and utilization of the natural resources of oil and gas in the state of Colorado in a manner consistent with protection of public health, safety, and welfare, including protection of the environment and wildlife resources.”[81] The Colorado Supreme Court interpreted this language as requiring a balancing test between development and environmental protection and required the Commission to first take into consideration cost-effectiveness and technical feasibility.[82] SB 19-181 changed the language to read that it is in the public interest to “[r]egulate the development and production of the natural resources of oil and gas in the state of Colorado in a manner that protects public health, safety, and welfare, including protection of the environment and wildlife resources.”[83] Section 12 of SB 19-181 goes further and directs the Commission to “protect and minimize adverse impacts to public health, safety, and welfare, the environment, and wildlife resources and . . . protect against adverse environmental impacts on any air, water, soil, or biological resource resulting from oil and gas operations.”[84]

Importantly, the Colorado legislature removed the terms “balanced” and “foster” and changed the language from “in a manner consistent with the protection” to “that protects.”[85] By removing the word “foster,” the Commission is no longer required to encourage oil and gas production. By removing the term “balanced,” a court would likely be unable to interpret the law to suggest that the Commission is bound by any sort of balancing test. Rather, the Commission is bound by a requirement that environmental protection is a condition that must be fulfilled when it issues permits or regulates oil and gas production.

In response to the amendments to Section 6 of SB 19-181, the Commission conducted a rulemaking in 2020 to make its regulations consistent with its amended mission. Commission Rule 301 states that the Commission “will approve operations only if they protect and minimize adverse impacts to public health, safety, welfare, the environment, and wildlife resources, and protect against adverse environmental impacts on any air, water, soil, or biological resource resulting from Oil and Gas Operations.”[86] This rulemaking indicates that the Commission, in an effort to conform with the directives of SB 19-181, must scrutinize the permit applications to ensure that oil and gas producers mitigate environmental effects and protect against adverse environmental impacts. Furthermore, it provides a basis for the Commission to deny permit applications if these environmental requirements are not met in the application itself and throughout the process.

Finally, a subsequent law, SB 23-285, changed the name of the Commission from the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission to the Energy and Carbon Management Commission and expanded the Commission’s regulatory authority to include geothermal resources.[87] This new name lends support to the Commission’s shift in emphasis and purpose from developing oil and gas resources towards an environmental agency tasked with managing carbon from the state of Colorado.

B. Alterations to the Statutory Definition of “Waste” and “Minimize Adverse Impacts”

Before the passing of SB 19-181, “waste” was defined as a diminution in the quantity of oil or gas that ultimately may be produced, meaning that oil and gas left in the ground could be considered wasteful.[88] SB 19-181 added to the definition a clause stating that waste “[d]oes not include the nonproduction of gas from a formation if necessary to protect public health, safety, and welfare, the environment, or wildlife resources as determined by the commission.”[89] This amended definition was likely aimed at correcting a justification the Colorado Supreme Court used in Longmont, which held that local authority was preempted by the Commission, in part, because inconsistent local regulations could create a patchwork effect that could ultimately lead to the inefficient extraction and diminution of natural resources and thus resulted in waste.[90] Further, this new definition of waste is one of the only places within SB 19-181 where the possibility of keeping oil in the ground is mentioned explicitly.

SB 19-181’s revised definition of “minimize adverse impacts” eliminated language requiring the Commission to “take into consideration the cost-effectiveness and technical feasibility” when making a decision to minimize adverse impacts, which could provide a legal basis for leaving oil and gas in the ground.[91] The court in Martinez relied upon this “cost effectiveness and technical feasibility” language to determine that the law envisioned some possible environmental and public health risks.[92] SB 19-181 also replaced the language “wherever reasonably practicable” with

to the extent necessary and reasonable to protect public health, safety, and welfare, the environment, and wildlife resources, to: (a) Avoid adverse impacts from oil and gas operations; on wildlife resources; and (b) Minimize and mitigate the extent and severity of those impacts that cannot be avoided.[93]

This amended language is significant in that it uses “avoid” first and then “minimize and mitigate” second. The placement of this language suggests that the Colorado legislature intended to grant the Commission the discretion to keep oil and gas in the ground where it was determined to be necessary and reasonable to protect the environment.

Under SB 19-181’s revised definition, minimizing adverse impacts no longer necessarily means that some possible environmental and public health risks are acceptable. Instead, it suggests that the Commission, in its decision to minimize adverse impacts, could allow development only if it eliminates environmental and public health risks. Because oil and gas production inevitably contributes to climate change, this new definition could be used as a basis to eliminate oil and gas production altogether.

C. SB 19-181’s Alteration of the Regulatory Framework to Allow for Local Regulation

While Longmont indicated that state regulation of oil and gas preempted any local regulation, SB 19-181 amended the law to ensure that local governments could play a role in regulating oil and gas.[94] Section 4 of SB 19-181 ensures that local governments have the authority to regulate the location of oil and gas production, inspect oil and gas facilities, and impose fines for leaks, spills, and emissions.[95] The amendments also allow local governments to fine operators to cover the reasonably foreseeable direct and indirect costs of permitting, regulating, inspecting, and monitoring.[96] Section 17 clarifies that local governments are not preempted by state agencies.[97] Based on these alterations, the Commission promulgated Rule 302 which requires operators to submit Oil and Gas Development Plans that ensure that they are conforming with local regulations.[98] The Commission rules also confirm that local governments can request to consult with an operator who has submitted an Oil and Gas Plan about necessary and reasonable measures to avoid and mitigate public health and environmental impacts.[99]

Together these alterations to the regulatory framework empower local governments with extensive regulatory and veto powers. This framework allows local governments that desire a leave-it-in-the-ground approach to do so by denying permits or making compliance with the regulations prohibitively burdensome. While these alterations allow for keeping it in the ground to be possible in some areas, it does not provide a statewide solution for doing so.

D. SB 19-181’s Setback and Alternative Location Analysis Requirements

Section 12 of SB 19-181 instructs the Commission to adopt rules that require an alternative analysis process for oil and gas facilities that are proposed to be located near populated areas.[100] Following the passage of SB 19-181, the Commission updated their regulations in January of 2021, creating a new setback requirement of 200 feet from buildings, public roads, and utility lines and 2,000 feet from schools and childcare facilities.[101] Oil and gas facilities cannot be sited less than 500 feet from residential buildings and require the informed consent of all tenants and owners for any facility less than 2,000 feet away from a residential building.[102]

New Commission regulations also require the oil and gas producer to conduct and fund an Alternative Location Analysis to obtain a permit under certain circumstances.[103] The analysis requires operators to supply maps, data, and a variety of information, including a list of all government organizations and parties that may have an interest in or jurisdiction over the siting of wells.[104] Importantly, the analysis also requires an oil and gas producer to include all technically feasible alternative locations.[105] This analysis is triggered if the proposed location is within 2,000 feet of any residential building, school, or daycare, or within 2,000 feet of a municipality or county border and that local government objects to the facility.[106] Additional triggers include when the facility is located within 1,500 feet of a “Designated Outside Activity Area,” within a wetland, a high priority habitat, within a surface water supply area, or near a public water system supply area.[107]

These setback requirements could create a significant hurdle for oil and gas development by reducing the number of facility locations and by empowering tenants and property owners to make the process of siting facilities slower, prohibitively expensive, or impossible. More stringent setback regulations will likely result in siting of any new oil and gas facilities further and further outside of populated areas, which are becoming fewer and fewer as Colorado’s population continues to grow and population centers continue to sprawl.[108] The Alternative Location Analysis adds an additional administrative hurdle that could increase the cost of oil and gas production in certain areas and could provide a basis for environmentalists, homeowners, or other parties to challenge a Commission permitting decision when the Alternative Location Analysis appears inadequate or reveals technically feasible alternative locations. The development of this requirement represents a powerful tool for keeping oil and gas in the ground and a departure from the Commission’s original emphasis on efficient production.

E. SB 19-181’s Mandate Requiring the Commission to Conduct a Rulemaking Addressing Cumulative Impacts

Alongside SB 19-181’s mandate requiring the Commission to promulgate rules addressing the Alternative Location Analysis is a mandate directing the Commission to “evaluate and address the potential cumulative impacts of oil and gas development” in consultation with the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment (“CDPHE”).[109] The statute did not define cumulative impacts further nor directly recognize climate change as an impact of oil and gas production. However, because climate change is indisputably a cumulative impact of oil and gas production and export, the language “cumulative impacts” provides an opportunity to incorporate Colorado’s climate goals into the decision-making process. This amendment could be utilized to require the Commission to assess the cumulative impact of Colorado’s production and exportation of oil and gas on climate change and limit continued production.

In the initial rulemaking following the passing of SB 19-181, the Commission stated that it would assess cumulative impacts taking into account information from the APCD and the AQCC regarding the current status of the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Reduction Roadmap.[110] On January 4, 2022, the Commission issued a report on the evaluation of cumulative impacts, which inventoried the extent to which oil and gas production has contributed to climate change.[111] Notable within the report are findings from the APCD, which highlight that on the western slope on average 35.5 tons per well per year of methane are leaked in preproduction and 13.4 tons per well per year of methane are leaked during production.[112] Importantly, in its discussion of greenhouse gas emissions, the report only identified emissions that occurred within the state and did not recognize cumulative impacts created by the combustion of oil and gas that is exported from Colorado.[113] Further lacking in the report were any recommendations of a potential rule that may provide guidance on how to address the cumulative climate impacts of oil and gas production in Colorado.

While the Commission did not immediately initiate a rulemaking process to define “address the potential cumulative impacts” on its own, several non-profits including WildEarth Guardians, 350 Colorado, Womxn from the Mountain, the Sierra Club of Colorado, and others, submitted a petition for a rulemaking.[114] In their petition, they proposed a number of potential rules, but specifically suggested defining cumulative impacts as “the total effects on a resource, ecosystem, or human community of that action and all other activities affecting that resource no matter what entity (federal, non-federal, or private) is taking the actions.”[115] While these environmental groups recognized that a single rulemaking could not address all cumulative impacts, they urged the Commission in their petition to focus on air emission in particular. To address these cumulative impacts, they proposed the following rule:

The Director shall not accept and the Commission shall not approve applications for Comprehensive Area Plans, Oil and Gas Development Plans, Form 2A Location Assessments, or Form 2 Applications for Permit to Drill, if the state has determined that it is not reaching statewide greenhouse gas emissions reductions targets. The Commission may resume issuance of these approvals only upon a formal showing by the CDPHE that the state’s greenhouse gas emissions reduction inventory shows attainment with the target emissions reductions.[116]

This proposed rule aims to use cumulative impacts as a primary mechanism to keep oil and gas in the ground by requiring the Commission to address impacts in a substantive way.

On December 9, 2022, the Commission held a hearing in which a representative from WildEarth Guardians presented the proposed rules.[117] While the commissioners recognized that they needed to conduct a rulemaking defining and addressing cumulative impacts, they seemed interested in gathering more perspectives through a “working group” rather than simply adopting the proposed rules.[118] WildEarth Guardians suggested that a working group could be considered a delay tactic, and urged the Commission to act.[119] Because a rulemaking forcing the Commission to evaluate and address cumulative impacts is so potentially expansive in scope and far-reaching in its ability to keep oil and gas in the ground, any decisions by the Commission following this hearing will likely be the subject of litigation by both environmental groups and industry representatives.

On February 28, 2023, the Commission issued a second report on the evaluation of cumulative impacts.[120] This report relied on updated data from forty-seven oil and gas development plans that had been approved in 2022, and constituted a significantly larger sample size than the seven oil and gas development plans that had provided the data for the first report.[121] The second report noted that while natural gas development in Colorado had increased over ninety percent from 2005 to 2019, emissions from the sector had only increased one and a half percent as a result of increased regulatory actions taken by the state.[122] The report also relied on statements from the APCD explaining that the oil and gas sector was likely to meet and exceed the climate targets created by the state.[123]

However, like the first report, this statement offered no recommendations for a Commission rule addressing cumulative impacts nor acknowledged the cumulative effect of the export and combustion of oil and gas in its evaluation of greenhouse gas emissions.[124] Without acknowledging Colorado’s contribution to climate change from its export of natural gas, the Commission’s evaluation of its cumulative impacts was likely legally inadequate. Furthermore, without a rulemaking discussing how it intends to address cumulative impacts, Colorado has not fulfilled its statutory obligation.

Finally, Colorado lawmakers added a firm deadline of April 28, 2024 for the Commission “to promulgate rules that evaluate and address the cumulative impacts of oil and gas operations.”[125] Additionally, the law clarified that in developing rules and a definition of “cumulative impacts[,]” “the Commission shall review, consider, and include addressable impacts to climate, public health, the environment, air quality, water quality, noise, odor, wildlife, and biological resources, and to disproportionately impacted communities . . . .”[126]

F. SB 19-181’s New Pooling Requirements

While SB 19-181 left most of the forced pooling scheme in place, they added some additional requirements that could empower non-consenting owners. Previously “any interested person” could file an application with the Commission to force pooling. Under SB 19-181 amendments, before an application for forced pooling can be filed with the Commission, the operator must own or secure the consent of owners of more than forty-five percent of the mineral interests of the shared reservoir.[127] Additionally, the operator must demonstrate that they tendered a good faith offer to every owner of a mineral interest sixty days before they can submit an application for forced pooling.[128]

These new requirements may have the effect of slowing down and driving up the price of new oil and gas development. The original pooling scheme focused on protecting correlative rights and efficient development by allowing oil and gas producers to circumvent non-consenting owners through the powerful forced pooling mechanism. The new regulations make this administrative mechanism significantly more difficult to use for oil producers as they must fulfill a series of more exacting requirements before they can file an application with the Commission.

III. Assessment of the Effectiveness of SB 19‑181 in Limiting Oil and Gas Production

Since its enactment, SB 19-181 has demonstrated varying degrees of effectiveness at keeping oil and gas in the ground. Production indicators provide a confusing picture: despite dropping 143 percent from the start of the first quarter of 2020 (likely as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic), oil and gas production rebounded by the second quarter of 2022, returning to within thirteen percent of the quarter one 2020 levels.[129] Similarly, policy and regulatory decisions at both the state and local level have provided mixed signals. At the local level, there are signs that SB 19-181 has been effective in limiting oil and gas production in some counties while having only a small effect in others. Similarly, at the state level, the Commission indicates a mix of priorities. On the one hand, it has permitted a significant number of new oil and gas developments, and on the other it has wielded its regulatory power against producers who have failed to comply with the new law.

A. The Effect of Local Regulation on Oil and Gas Production

Reports issued by local governments suggest that SB 19-181 has had a significant, but localized, impact. Section 4 and Section 17 of SB 19-181 ended the state preemption of oil and gas regulation. As a result, local governments have been empowered to impose fines, reject the proposed siting of wells and facilities, inspect production facilities, and regulate to a standard that is potentially more stringent than the Commission’s standard.

Several local regulatory bodies opted to exercise their right to regulate oil and gas production, notably Boulder and Weld Counties. Within a year of the passing of SB 19-181, the Boulder County Community Planning & Permitting Department proposed and adopted Resolution 2020-95, amending the land use code to reflect their new power to regulate oil and gas development.[130] These amendments gave the Boulder County Board of Commissioners regulatory authority over all oil and gas development within the county.[131] The amendments indicate that Boulder County intends to regulate every potential effect of production, including odor, noise, spills, leaks, water quality, vegetation, and emissions.[132] It also intends to extend its regulations to new, pre-existing, and decommissioned facilities, the exploration of new oil and gas resources, and pipelines.[133] Oil and gas producers have to go through a complicated application process which requires applicants to include very detailed plans related to the site location, road-building, water quality, weed control, dust control, lighting, revegetation, emergency preparedness, flood protection, and others.[134] They are required to use verified outside experts to study the effect of the oil and gas development on air quality, soil conditions, agriculture, wildlife, natural resource depletion, water quantity, noise, odor, cultural and historical resources, and other effects.[135] The new regulations declare that “the Board will deny the Application if the proposed oil and gas facilities or operations cannot be conducted in a manner that protects public health, safety, and welfare, the environment and wildlife,” essentially granting the Boulder County Board of Commissioners veto power.[136]

Following SB 19-181, Weld County’s Board of Commissioners approved amendments to the County’s oil and gas law with the passing of Weld County Ordinance 2020-12 and the creation of the Weld County Oil and Gas Energy Department.[137] As the largest oil and gas producing county within the state of Colorado, Weld County’s regulation of oil and gas production is especially significant.[138] Like Boulder County, Weld County has a special permitting process for the siting of oil and gas production facilities.[139] It also requires a rigorous application process and numerous plans to address specific aspects of production like waste management, lighting, road building, dust mitigation, noise mitigation, and others.[140] Following a hearing, Weld County also has the power to deny a permit if the producer’s plans are inadequate.[141]

However, despite the existence of new local regulations, the degree to which Boulder and Weld County kept oil and gas in the ground has varied significantly. Boulder County reported that “no operators applied to the county to drill in 2021 and no applications are pending at the state level.”[142] Despite the existence of significant oil and gas resources within the county, Boulder County only produced 37,328 barrels of oil in 2021, down from a high in 2010 of 239,062 barrels of oil.[143]

Furthermore, Boulder has fought to keep its oil and gas resources in the ground through legal action when it filed a motion on November 21, 2022, urging the Commission to reject an application for forced pooling submitted by Extraction Oil & Gas, Inc.[144] Extraction had sought to drill diagonally from Weld County into 552 acres of mineral rights owned by Boulder County.[145] When Boulder County refused to lease these rights, Extraction filed an application for forced pooling.[146] In the motion to the Commission, Boulder County argued that the Commission did not have the authority to force the pooling of mineral rights owned by government entities in Colorado under both the Colorado Constitution and the statutory provisions created under SB 19-181.[147] Specifically, Boulder contested the forced pooling on several bases. First, while a public purpose exception potentially allows governments to constitutionally mingle public money and property with private parties, “the private, for-profit use of government property against the express will of those governments does not fall within this exception.”[148] Second, Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights prevents governments from entering into financial obligations “in the absence of a legislative measure and an election.”[149] Third, the forced pooling of its mineral rights contravened its statutory obligations to ensure that it enters into transactions that are in the “best interest of the county” under C.R.S. § 30-11-303(1).[150] Fourth, the forced pooling action infringes on the Board of County Commissioners’ exclusive authority to manage county budgets under C.R.S § 30-11-107(2)(a).[151] Finally, Boulder argued that forced pooling of its mineral rights violated the common law doctrine of purpresture, meaning “the appropriation to private use of that which belongs to the public.”[152]

However, despite the new role for local government as a regulator following SB 19-181, its effect on oil and gas development likely depends on the political and cultural preferences of each county. For example, in stark contrast to Boulder County, Weld County approved twenty-six of the twenty-nine permit applications it received in 2022.[153] Further, it produced a total of 131,293,051 barrels of oil in 2021, reflecting a significant increase from 2010 when it produced 21,112,660 barrels of oil.[154] Notably, Weld County and the Commission also approved PDC Energy’s Guanella plan, allowing 466 wells on 33,000 acres.[155]

B. The Effect of SB 19-181 on the Administrative Practices of the Commission

Despite SB 19-181’s overhaul of the Commission’s regulatory powers and purpose, evidence of the agency’s actions has yet to reflect a significant shift in its priorities away from the fostering of balanced development towards regulating production in a manner that substantively protects the environment. The Commission is continuing to allow oil and gas development to continue at a rapid rate, suggesting that the agency has yet to utilize the authority granted in SB 19-181 to limit or slow oil and gas production. Nevertheless, since the passing of 19-181, the Commission has also revoked permits under certain circumstances and enforced the most egregious violations, indicating that it can wield strong regulatory power in some situations.

In 2022, the Commission approved seventy-eight Oil & Gas Location Assessments and fifty-four Oil & Gas Development Plans.[156] Also in 2022, the Commission approved two massive Comprehensive Area Plans (“CAPs”) and are considering a third.[157] CAPs are plans aimed to address impacts from oil and gas development in a broad geographic area by identifying plans for one or more operators to develop oil and gas locations within a region.[158] For example, the Guanella CAP covers 466 wells at twenty-five different locations.[159] The Commission is also considering the 37,520-acre Crestone Peak Resources Box Elder CAP, which includes 151 wells on twenty different sites.[160] The continued approval of oil and gas plans in 2022 suggest that the Commission continues to embrace its original mission of fostering oil and gas development.

However, there is also evidence that the Commission is willing to force oil companies to conform to the new regulations. In March 2021, the Commission rejected an application by Kerr-McGee to drill thirty-three wells that were within the 2000-foot setback requirement for eighty-seven homes.[161] The Commission found that Kerr-McGee had not adequately considered alternatives or provided sufficient evidence that it would apply the best-management practices recommended by the CDPHE.[162] In July 2021, the Commission exercised its regulatory powers and took control of 106 wells owned by 31 Operating and Lasso Oil and Gas mostly in Rio Blanco County.[163] Despite finding that taking ownership of the wells was necessary after a series of violations including failing to clean up a spill, allowing the venting or flaring of gas, and failing to maintain a wellhead, the Commission suspended 2.2 million in fines.[164] In May 2021, the Commission ordered KP Kaufman, a Colorado-based oil and gas company, to shut down eighty-seven wells after it discovered numerous violations, including leaving oily waste that ruined farm fields and failing to properly address spills.[165] In June of 2022, after months of negotiations on the clean-up and the fines, the Commission gave KP Kauffman six months to ensure that it cleans up and pays a significant portion of the two million dollar fine or the levied $3.7 million in fines levied against KP Kauffman after regulators discovered twenty alleged operating violations at seven different sites.[166] While the Commission has deferred payment of most of the fines, the agency has threatened to potentially suspend KP Kauffman’s ability to sell oil and gas and halt all approvals for any new oil and gas development.[167]

IV. Legal Mechanisms to Potentially Challenge Colorado’s Oil and Gas Production

SB 19-181, the Commission rulemaking that followed, and the administrative decisions of the Commission have yet to substantially slow development or keep most oil and gas in the ground. However, additional rulemakings have the potential to substantially curb oil and gas production. First, environmental advocates can and are in the process of bringing a rulemaking focused on cumulative impacts under the language of SB 19-181 that provides a strong opportunity to keep oil and gas in the ground. Second, there is also a real but less promising opportunity to implement a rulemaking that keeps oil and gas in the ground using the language of the Colorado Constitution.

A. SB 19-181 Likely Enables a Rulemaking Designed to Keep Oil and Gas in the Ground

The rule proposed by the plaintiffs in Martinez provides one example of a possible rule that is likely consistent with the language of SB 19-181. The proposed rule stated that the Commission should not issue permits “unless the best available science demonstrates, and an independent third-party organization confirms, that drilling can occur in a manner that does not cumulatively, with other actions, impair Colorado’s atmosphere, water, wildlife, and land resources, does not adversely impact human health, and does not contribute to climate change.”[168]

The Colorado Supreme Court’s decision in Martinez hinged on three points: (1) the standard of review surrounding the question of whether the agency must engage in a rulemaking was too deferential for the plaintiffs to overcome; (2) the duty of the Commission was to first foster oil and gas development and protect the rights of owners and producers, and second, to prevent and mitigate significant environmental impacts only after taking into consideration cost-effectiveness and technical feasibility; and (3) the Commission reasonably relied on the knowledge that it was working with the CDPHE on the issue the proposed rule aimed to address.[169]

SB 18-191 created overlapping mandates that directly undermine the basis for the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision in Martinez. First, C.R.S. § 34–60–106(11)(d) requires the Ccommission to develop rules to evaluate and address cumulative impacts, eliminating any ability for the Commission to continue to delay.[170] Second, the amendments to the Commission mission statement now require the Commission to “[r]egulate the development and production of the natural resources of oil and gas in the state of Colorado in a manner that protects public health, safety, and welfare, including protection of the environment and wildlife resources”[171] and to “protect and minimize adverse impacts to public health, safety, and welfare, the environment, and wildlife resources and shall protect against adverse environmental impacts on any air, water, soil, or biological resource resulting from oil and gas operations.”[172] The plain language of these statutory provisions indicates that the duty of the Commission is to prevent and mitigate significant environmental impacts over any requirement to foster oil and gas development and protect the rights of owners and producers. Third, amendments to the law indicate that the Commission has a duty as an environmental regulator and can no longer reasonably rely on the knowledge that the CDPHE also deals with the cumulative impacts of climate change. The operative words in its mission and mandates are “regulate,” “protect,” “minimize,” and “address.” This language requires the Commission to operate as an independent environmental regulator. While the Commission can of course collaborate with other state agencies, it cannot neglect its duty as a regulator or avoid its duty to protect the environment while continuing to primarily fulfill its former mission of fostering oil and gas development.

Because SB 19-181 directly amended the law in a way that undermined the justifications relied upon by the Colorado Supreme Court in Martinez, if the Commission were to adopt this rule, a legal challenge by industry would likely be unsuccessful. However, because oil and gas drilling contributes to climate change, this version of the rule would functionally end new oil and gas development in Colorado. As a result, it is unlikely to be approved by the Commission despite being a permissible construction of the law.

The rule proposed by WildEarth Guardians provides another possible version of a rule that could function to keep oil and gas in the ground and stands a stronger chance of being approved by the Commission.[173] This rule first defines cumulative impacts of air emissions, and then lays out a way to address them.[174] The rule would require the Commission to not approve Comprehensive Area Plans, Oil and Gas Development Plans, Location Assessments, or permits if the state is not reaching its greenhouse gas emissions targets.[175] The rule is both consistent with the language of SB 19-181 and requires the Commission to consider its climate targets. As Colorado has passed aggressive climate targets focused on reducing emissions in the oil and gas industry, this rule provides an opportunity to harmonize the AQCC’s climate reduction with the permitting practices of the Commission.

Arguably, this rule does not go far enough to keep oil and gas in the ground because it first requires a finding that AQCC has not met its thirty-six percent reduction target by 2025 or its sixty percent reduction target by 2030. Thus, it may take several years before the Commission would be required to stop permitting new oil and gas production. Furthermore, because these reduction targets do not account for the greenhouse gases created from the combustion of oil and gas that is exported from Colorado, basing the cumulative impact rule on Colorado’s climate targets avoids dealing with a significant percentage of the actual cumulative impacts of oil and gas production.

At the time of this note, the Commission is hearing rule proposals and is imminently close to promulgating a final rule to meet the April 28, 2024 deadline. While the eventual rule promulgated by the Commission may change the analysis, this note outlines the limits and potential of a new rule and could serve as a guide to environmental advocates.

B. The Colorado Constitution Provides an Unlikely Basis to Challenge the Continued Production of Oil and Gas Without Addressing Cumulative Impacts

The plaintiffs in Martinez challenged the Commission under both the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Act and the Colorado Constitution.[176] The plaintiffs contended that the Commission decision rejecting the plaintiff’s proposed rule violated Article 2, Sections 3 and 28 of the Colorado Constitution.[177] Section 3 states, “All persons have certain natural, essential and inalienable rights, among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; of acquiring, possessing and protecting property; and of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness.”[178] Section 28 states, “The enumeration in this constitution of certain rights shall not be construed to deny, impair or disparage others retained by the people.”[179] Therefore, the plaintiffs argued that they had retained the right to a “healthful and pleasant natural environment.”[180] Further, they argued that the numerous laws passed by the Colorado Legislature to protect the air, water, wildlife, natural areas, and public health, including earlier versions of the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Act, acknowledge this inherent right.[181]

The Denver District Court rejected the Martinez plaintiffs’ arguments on both statutory and constitutional grounds, stating that the balancing of multiple factors when regulating oil and gas was “not inconsistent with the Colorado Constitution.”[182] When the Colorado Court of Appeals overturned the district court’s holding, the court applied the canon of constitutional avoidance—the judicial preference to avoid a constitutional analysis in favor of a statutory resolution[183]—by choosing to overrule the district only on statutory grounds.[184]

While the Colorado Supreme Court never reviewed the merits of the Martinez plaintiffs’ constitutional argument, they did briefly address a similar argument in Longmont. In that case, citizen intervenors argued that Section 3 of Article 2 reigned supreme over any state statute and thus allowed local regulation alleged to concern life, liberty, property, safety, or happiness to always supersede state law.[185] The court held that this provision protects fundamental rights from abridgement by the state only if there is no compelling government interest.[186] However, the court also held that this provision of the Constitution did not apply to preemption of state law.[187]

The rulings in Martinez and Longmont demonstrated an unwillingness of Colorado courts to apply the inalienable rights provision in oil and gas law cases, particularly when there are relevant statutes at issue. As SB 19-181 already provides a number of opportunities to keep oil and gas in the ground, a court in Colorado is likely going to be unwilling to entertain an effort to keep oil and gas in the ground using the Colorado Constitution.

Conclusion

In order to uphold its commitment to fight climate change, Colorado should make every effort to keep oil and gas in the ground. The SB 19-181 amendments to Colorado’s oil and gas law provide a number of avenues to keeping oil and gas in the ground by limiting and delaying production. These include amendments and mandates surrounding the Commission’s mission statement, alterations to the definitions of “waste” and “minimize adverse impacts,” increases in local control, changes to the forced pooling requirements, new setback and alternative location analysis requirements, and a new Commission mandate to evaluate and address cumulative impacts. However, despite these additional requirements, increased costs for oil producers, and new mandates requiring the Commission to prioritize and address environmental issues, the Commission continues to permit oil production and exploration at a rapid and unsustainable pace, potentially compromising its goals.

In particular, the cumulative impact provision, because of its direct application to climate change-causing effects of oil and gas production and export, provides the best opportunity to keep oil and gas in the ground. In the near future, the Commission is expected to issue a rulemaking defining and addressing cumulative impacts of oil and gas production and exploration. If the rulemaking decision continues to allow the permitting of new wells and development plans without substantively addressing oil and gas production’s impact on climate at every stage of the production and exportation processes, environmental advocates have a strong case to challenge this decision in the Colorado courts.

- *J.D. Candidate, 2024, University of Colorado Law School. ↑

- Climate Action Plan to Reduce Pollution Act, H.B. 19-1261 § 1(2)(g), 2019 Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Colo. 2019) (codified at Colo. Rev. Stat. § 25-7-102(2)(g)). ↑

- Protect Public Welfare Oil and Gas Operations Act, S.B. 19-181, 2019 Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Colo. 2019) (codified at Colo. Rev. Stat. §§ 34-60-101 to 133) (amending the Oil and Gas Conservation Act). ↑

- GHG Pollution Reduction Road Map 2.0, Colo. Energy Off., https://energyoffice.colorado.gov/climate-energy/ghg-pollution-reduction-roadmap (last visited Mar. 28, 2023). ↑

- Environmental Justice Disproportionate Impacted Community Act, H.B. 21-1266 § 14, 2021 Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Colo. 2021) (codified at Colo. Rev. Stat. § 25-7-105(1)(e)(XII)). ↑

- 5 Colo. Code Regs. § 1001-9 (2023). ↑

- Energy and Carbon Management Regulation in Colorado, S.B. 23-285 § 1, 2023 Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Colo. 2023) (codified at Colo. Rev. Stat § 34-60-104.3); Pollution Protection Measures, H.B. 23-1294 § 6, 2023 Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Colo. 2023) (codified at Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-106(11)(d)). ↑

- Colo. Oil & Gas Conservation Comm’n, Rule 904(a) Report on the Evaluation of Cumulative Impacts 12 (Jan. 2022), https://cogcc.state.co.us/documents/ library/Cumulative_Impacts/2021_COGCC_CI_Report_20220114.pdf; Tim Taylor, Colo. Air Pollution Control Div., Colorado 2021 Greenhouse Gas Inventory Update 4, 16 (Sept. 2021), https://drive.google.com/file/d/1SFtUongwCdZ vZEEKC_VEorHky267x_np/view. ↑

- Taylor, supra note 7, at 75. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Natural Gas Annual Supply & Disposition by State, U.S. Energy Info. Admin., https://.eia.gov/dnav/ng/ng_sum_snd_dcu_sCO_a.htm (last visited Feb. 17, 2024); Danny Bishop, The long and winding road: Weld County’s oil travels the distance to local, worldwide markets, Greeley Trib. (May 13, 2020, 5:08 AM), https://www.greeleytribune.com/2017/08/13/the-long-and-winding-road-weld-countys-oil-travels-the-distance-to-local-worldwide-markets/; See GHG Pollution Reduction Road Map 2.0, supra note 3, at IV. ↑

- See Mark Jaffe, Colorado oil and gas companies said a 2019 state law would destroy them. That didn’t happen. But here’s what did, Colo. Sun (July 6, 2022), https://coloradosun.com/2022/07/06/colorado-oil-gas-laws-new-drilling-permits/; State Land Board, Colo. Dep’t Nat. Res., https://dnr.colorado.gov/divisions/state-land-board (last visited Feb. 17, 2024). ↑

- GHG Pollution Reduction Roadmap, Report Drafts and Modeling Assumptions: Production Forecasts, Oil and Gas, Colo. Energy Off., https://drive.google.com/file/ d/1J-gylkTbmbmknsQcfNRTlF1EbdwBxjVx/view (last visited Feb. 17, 2024). ↑

- 2021 Report: The Production Gap, UN Env’t Programme 3 (2021), https://productiongap.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/PGR2021_web_rev.pdf. ↑

- See id. ↑

- Christina Nunez, Fossil fuels, explained, Nat’l Geographic (Apr. 2, 2019), https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/fossil-fuels. ↑

- See 5 Colo. Code Regs. § 1001-9 (2023). ↑

- See Keeping it in the Ground, Ctr. for Biological Diversity, https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/keep_it_in_the_ground/ (last visited Feb. 17, 2024); see also Eric Biber & Jordan Diamond, Keeping it all in the Ground?, 63 Ariz. L. Rev. 279, 282 (2021). ↑

- See Biber & Diamond, supra note 17. ↑

- Id. at at 280–81. ↑

- Id. at 286, 303. ↑

- Niobrara Shale Overview, Shale Experts, https://www.shaleexperts.com/plays/ niobrara-shale/Overview (last visited Feb. 17, 2024); Colorado State Energy Profile: State Profile and Energy Estimates, U.S. Energy Info. Admin., https://www.eia.gov/state/analysis.php?sid=CO (last updated May 18, 2023). ↑

- Colorado State Energy Profile: Colorado Quick Facts, U.S. Energy Info. Admin., https://www.eia.gov/state/print.php?sid=co (last updated May 18, 2023); Jessica Aizarani, Crude oil production in the United States in 2021, by state, Statista (Jan. 31, 2023), https://www.statista.com/statistics/714376/crude-oil-production-by-us-state/. ↑

- Id. ↑

- See id. ↑

- Niobrara Shale Overview, supra note 21. ↑

- Id.; Bakken Region Drilling Productivity Report, U.S. Energy Info. Admin. (Jan. 2024), https://www.eia.gov/petroleum/drilling/pdf/bakken.pdf; cf. Colorado Field Production of Crude Oil, U.S. Energy Info. Admin. (Apr. 2024), https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=pet&s=mcrfpco2&f=m (indicating that Colorado produced between 429,000 and 485,000 barrels of crude oil per day in every month of 2023). ↑

- Ben Markus, Natural Gas Drilling May Never Boom Again For Western Colorado, CPR News (Nov. 1, 2017), https://www.cpr.org/2017/11/01/natural-gas-drilling-may-never-boom-again-for-western-colorado/. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Colorado changes its regulatory structure for oil and natural gas production, U.S. Energy Info. Admin. (Jun. 27, 2019), https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php? id=39993. ↑

- B.A. Wells & K.L. Wells, Exploring Colorado Oil History, Am. Oil & Gas Hist. Soc’y, https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/exploring-boulder-oilfield-history/ (last updated Aug. 6, 2022). ↑

- Colorado Field Production of Crude Oil, U.S. Energy Info. Admin., https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=MCRFPCO1&f=M (last updated Feb. 29, 2024); Colorado Natural Gas Gross Withdrawls, U.S. Energy Info. Admin., https://www.eia.gov/dnav/ng/hist/n9010co2m.htm (last updated Feb. 29, 2024). ↑

- Natural Gas Annual Supply, supra note 10; Bishop, supra note 10. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Robert E. Hardwicke, The Rule of Capture and Its Implications As Applied to Oil and Gas, 13 Tex. L. Rev. 391, 393 (1935); Tara K. Righetti, The Incidental Environmental Agency, 2020 Utah L. Rev. 685, 692–93 (2020). ↑

- Bryan H. Druzin, The Parched Earth of Cooperation: How to Solve the Tragedy of the Commons in International Environmental Governance¸ 27 Duke. J. Comp. & Int’l L. 73, 75 (2016). ↑

- Righetti, supra note 34, at 93. ↑

- Id. at 693. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 694. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 696–97; Hardwicke, supra note 34, at 410–12. ↑

- See H.B. 347, 38th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Colo. 1951). ↑

- Id. § 4–5. ↑

- Id. § 5. ↑

- Id. § 11. ↑

- Id. § 6(f)–(g). ↑

- Righetti, supra note 34, at 706. ↑

- Frequently Asked Questions Related to Statutory Pooling in Colorado, Colo. Oil & Gas Conservation Comm’n (Nov. 2018), https://cogcc.state.co.us/documents/about/ Help/Pooling Pamphlet.pdf [hereinafter Frequenty Asked Questions]. ↑

- Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-116 (2018). ↑

- Frequently Asked Questions, supra note 48. ↑

- See Righetti, supra note 34, at 707. ↑

- Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-102(1) (1979). ↑

- S.B. 94-177, 59th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Colo. 1994). ↑

- H.B. 07-1298, 66th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Colo. 2007). ↑

- See S.B. 94-177; H.B. 07-1298 § 1; see also H.B. 07-1341, 66th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. § 2 (Colo. 2007). ↑

- Colo. Const. art. II, § 15; Colo. Rev. Stat. §§ 7-43-102, 38-1-101.5, 38-2-101, 38-4-102, 38-5-104 (2023). ↑

- See Akin v. Four Corners Encampment, 179 P.3d 139, 145 (Colo. App. 2007). ↑

- City of Longmont v. Colo. Oil & Gas Ass’n., 369 P.3d 573, 577, 580–81 (Colo. 2016). ↑

- Colo. Oil & Gas Conservation Comm’n. v. Martinez, 433 P.3d 22, 25 (Colo. 2019). ↑

- Longmont, 369 P.3d at 576–77. ↑

- Id. at 577. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 577, 581. ↑

- Id. at 580. ↑

- Martinez, 433 P.3d at 25. ↑

- H.B. 07-1341, 66th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. § 2 (Colo. 2007). ↑

- Martinez, 434 P.3d at 693. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Martinez, 433 P.3d at 25. ↑

- Id. at 29. ↑

- Id. at 30. ↑

- Martinez, 433 P.3d at 31. ↑

- Id. at 25. ↑

- See Bill Summary, Protect Public Welfare Oil And Gas Operations, Colo. S.B. 19-181, Colo. Gen. Assembly., https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb19-181 [hereinafter Bill Summary]. ↑

- See S.B. 19-181, 74th Gen. Assemb., 2nd Reg. Sess. §§ 1–2, 4 (Colo. 2019). ↑

- See id. at §§ 6–7. ↑

- See id. at §§ 3, 11. ↑

- Id. at § 3. ↑

- See id. at §§ 4, 6–7, 12. ↑

- Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-102(1) (2018). ↑

- Colo. Oil & Gas Conservation Comm’n. v. Martinez, 433 P.3d 22, 30 (Colo. 2019). ↑

- S. B. 19-181, 74th Gen. Ass., 2nd Reg. Sess. § 6 (Colo. 2019) (codified as Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-102(1)(a)(I) (2019)). ↑

- Id. § 12(2.5)(a) (codified at Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-106(2.5)(a)). ↑

- Id. § 6. ↑

- Colo. Code Regs. § 404-1-301(a). ↑

- See Bill Summary, Energy and Carbon Management Regulation in Colorado, Colo. S.B. 23-285, Colo. Gen. Assembly., https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb23-285. ↑

- Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-103(11)–(13) (2012); see also Righetti, supra note 34, at 703 (explaining how traditional definitions of waste also meant the stranding of oil and gas underground). ↑

- S.B. 19-181, 74th Gen. Ass., 2nd Reg. Sess. § 7 (Colo. 2019) (codified as Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-103(11-13) (2019)). ↑

- City of Longmont v. Colo. Oil & Gas Ass’n., 369 P.3d 573, 580 (Colo. 2016). ↑

- S.B. 19-181, 74th Gen. Ass., 2nd Reg. Sess. § 7 (Colo. 2019) ↑

- Colo. Oil & Gas Conservation Comm’n. v. Martinez, 433 P.3d 22, 31 (Colo. 2019). ↑

- Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-103(5.5) (2019). ↑

- Bill Summary, supra note 74. ↑

- S.B. 19-181, 74th Gen. Ass., 2nd Reg. Sess. § 4 (Colo. 2019). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. § 17 (codified at Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-131 (2019). ↑

- Colo. Code Regs. §§ 404-1-302(b), (e) (2022). ↑

- Id. § 302(g). ↑

- S.B. 19-181, 74th Gen. Ass., 2nd Reg. Sess. § 12 (11)(c)(1) (Colo. 2019). ↑

- Colo. Code Regs. §§ 404-1-604(a)(1)–(3), (b) (2021). ↑

- Id. § 604(a)(3)–(4). ↑

- Id. § 304(b)(2)(A). ↑

- Id. § 304(b)(2)(C). ↑

- Id. § 304(b)(2)(C)(i)(cc). ↑

- Id. § 304(B). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Aldo Svaldi, Rebound in international immigration helped keep Colorado’s population growing last year, The Denver Post (Dec. 23, 2022), https://www.denverpost. com/2022/12/23/colorado-population-growth-census-international-immigration/. ↑

- S.B. 19-181, 74th Gen. Ass., 2nd Reg. Sess. § 12(II)(c)(2) (Colo. 2019) (codified at Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-106(11)(c)(2)). ↑

- Colo. Code Regs. § 904(a)(2). ↑

- Report on the Evaluation of Cumulative Impacts, Colo. Oil & Gas Conservation Comm’n (Jan. 4, 2022), https://cogcc.state.co.us/documents/library/Cumulative_Impacts/2021_COGCC_CI_Report_20220114.pdf. ↑

- Id. at 10. ↑

- See id. at 12–14. ↑

- See Press Release, WildEarth Guardians, Environmental groups submit a formal petition demanding Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission protect the public against cumulative impacts of oil and gas production (Aug. 31, 2022), https://wildearth guardians.org/press-releases/environmental-groups-submit-a-formal-petition-demanding-colorado-oil-and-gas-conservation-commission-protect-the-public-against-cumulative-impacts-of-oil-and-gas-production/; WildEarth Guardians et al., Petition for Rulemaking to Adopt Rules to Evaluate and Address Cumulative Air Impacts of Oil and Gas Development at 14 (2022), https://pdf.wildearthguardians.org/support_ docs/WildEarth-Guardians-350-Colorado-et-al-Rulemaking-Petition.pdf [hereinafter Petition for Rulemaking]. ↑

- Id. at 14. ↑

- Id. at 18. ↑

- Colo. Oil & Gas Conservation Comm’n, Cumulative Impact Rulemaking Hearing, YouTube (Dec. 9, 2022), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fF6CcoqMzBI&list=PLpwAEXLpeKyczjy7Q2oPFQLjq_28Hwx6W&index=7. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Colo. Oil. Conservation Comm’n, Report on the Evaluation of Cumulative Impacts (Feb. 2023), https://cogcc.state.co.us/documents/library/Cumulative_Impacts/2022%20CI%20Report_FINAL_2023-02-28.pdf. ↑

- Id. at 3. ↑

- Id. at 55. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Pollution Protection Measures, H.B. 23-1294 § 6, 2023 Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Colo. 2023) (codified at Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-106(11)(d)(I)). ↑

- Id. § 6 (11)(d)(II). ↑

- S. B. 19-181, 74th Gen. Ass., 2nd Reg. Sess. § 14 (Colo. 2019) (codified at Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-116 (6)(b)(i)). ↑

- Id. § 14 (codified at Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-116(7)(d)). ↑

- Memorandum from Greg Dean to Noel Bernal, Adams County Production and Drilling Update 5 (Sept. 23, 2022), https://adcogov.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/AdCo-ProductionUpdate-092322.pdf. ↑

- Boulder County Board of Commissioners, Res. 2020-95 Approving Proposed Land Use Code Amendments Addressing Oil and Gas Development, Seismic Testing, and Companion Changes to the Land Use Code 1 (Dec. 15, 2020), https://assets.bouldercounty.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Resolution-2020-95.pdf. ↑

- Id. at 12-1 to 12-2. ↑

- Id. at 12-2 to 12-5. ↑

- Id. at 12-2 to 12-8. ↑

- Id. at 12-9 to 12-23. ↑

- Id. at 12-18 to 12-23. ↑

- Id. at 12-27. ↑

- Code Ordinance 2020-12, Weld Cnty. (Weld Cnty., 2020), https://library.municode.com/co/weld_county/ordinances/charter_and_county_code?nodeId=1036514; Weld Cnty. Oil & Gas Energy, https://www.weld.gov/Government/Departments/Oil-and-Gas-Energy (last visited Feb. 3, 2024). ↑

- Reports Portal, Monthly Oil Production by Cnty., Colo. Oil & Gas Conservation Comm’n, https://ecmc.state.co.us/data4.html (last visited Jan. 26, 2024) [hereinafter Reports Portal]. ↑

- Code Ordinance 2020-12 1041 WOGLA Permit Program for Oil and Gas Exploration and Production in the Weld Mineral Resource (Oil and Gas) Area § 21-5-312, Weld Cnty. (Weld. Cnty., 2020), https://library.municode.com/co/weld_county/codes/charter _and_county_code?nodeId=CH21ARACSTIN_ARTVGUREOIGAEXPRUNARWE CODEMIREARSTIN_DIV31041WOPEPROIGAEXPRWEMIREOIGAAR. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. § 21-5-340 (1041 WOGLA Permit Hearing). ↑

- Boulder County Oil and Gas Update: Fewer Active Wells in Boulder County in 2021, Boulder Cnty. (Dec. 22, 2021), https://bouldercounty.gov/news/boulder-county-oil-and-gas-update-fewer-active-wells-in-boulder-county-in-2021/. ↑

- Reports Portal, supra note 137. ↑

- Boulder Cnty. Mot. for Summ. J. at 1, Promulgation and Establishment of Field Rules to Govern Operations for the Niobrara and Codell Formations, Warrenberg Field, Boulder and Weld Counties, Colorado (No. 220700180) (Nov. 21, 2022), https://assets.bouldercounty.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/cogcc-boulder-county-motion-for-summary-judgment-pooling-docket-220700180-20221121.pdf. [hereinafter Boulder Cnty. Motion for Summary Judgment]. ↑

- Boulder County Commissioners to examine proposal against threat of forced pooling, Boulder Cnty. (Oct. 24, 2022), https://bouldercounty.gov/news/boulder-county-commissioners-to-examine-proposal-against-threat-of-forced-pooling/. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Boulder Cnty. Motion for Summ. J., supra note 143, at 3. ↑

- Id. at 9. ↑

- Id. at 10–11 (internal citations omitted). ↑

- Id. at 12. ↑

- Id. at 14. ↑

- Id. at 15. ↑