It was April 2017 when a gas explosion destroyed a home in Firestone, Colorado and killed two people—brothers-in-law Mark Martinez and Joey Irwin.[2] The explosion was caused by a severed gas line, likely cut when the home was built years earlier.[3] In the investigation that followed, it was determined that non-odorous gas had been leaking into the family’s home for months.[4] The Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (“COGCC” or “Commission”) levied a fine against the oil and gas company responsible for the line that totaled $18.25 million—nearly eleven times the next largest penalty ever levied, which was against a different energy company in 2018.[5] The COGCC said those fines would be used to prevent accidents like Firestone from happening again, but despite the “ ‘never-again’ statements” made in light of the accident, spills and accidents still occur, with many being small enough to go unreported even in light of more stringent accident reporting requirements.[6] Oil and gas accidents and spills have numerous effects on the environment as well as public health and safety, from disrupting land use and wildlife to contributing to increased water and air pollution.[7]

Fast forward another year. In light of the Firestone accident and smaller incidents since, Colorado passed Senate Bill 19-181, also known as the “Protect Public Welfare Oil And Gas Operations” bill (“SB 19-181”), in April 2019, to address public welfare and environmental concerns regarding the oil and gas industry.[8] This statute altered the mission of the COGCC to prioritize public health, safety, and the environment in regulating the oil and gas industry in Colorado.[9] The bill required the COGCC to implement new rules in light of its mission change that requires consideration of public health and the environment in its regulatory decisions, grants more control to local governments, and increases the protections given to individuals who are forced to pool their development rights.[10]

While Colorado has taken a noteworthy step with the passage of Senate Bill 19-181 to prioritize public health and the environment in the context of oil and gas development, it could have, if not should have, gone further. Senate Bill 19-181 did not require sweeping changes to how the COGCC operates, instead leaving a fair bit of discretion up to the regulatory agency to decide how to move forward. Given the vague mission of the COGCC to prioritize protecting public health and the environment via SB 19-181’s new commitments, the COGCC’s recently passed rules implementing SB 19-181 improve avenues to accountability and prioritization of public health and the environment in some cases. The COGCC also could have done more if it included provisions such as increased notice for oil and gas operations, expanded access to the Commission by individuals advocating for themselves and their health, and created more incentives to encourage tighter regulations by local governments. It also could have introduced various incentives and reprimands to encourage the oil and gas industry to protect the environment as much as possible. Lastly, the use of ambiguous language in the COGCC rules will leave certain issues to be settled in the Colorado judiciary. As the courts have shown themselves to be pro-development (even following SB 19-181), there are concerns that meaningful implementation of protections for the public health and environment will be undermined here as well.

This Note will have four sections, beginning with a history of oil and gas in Colorado and an examination of the role the COGCC has in regulating industry. Following is an explanation of how the recently passed SB 19-181 alters the mission and priorities of the Commission to place greater importance on the protection of public health and environment. This Section also will analyze the rules recently changed by the COGCC and where they fall short. Then, it will consider relevant case law that may become relevant in the future as SB 19-181 and the COGCC rules are interpreted by the courts. Finally, this Note will end with a section detailing tangible steps and provisions the state legislature and the COGCC could have—and should have—taken to improve this attempt at better regulating and holding accountable the oil and gas industry in light of the climate crisis.

- A Brief History of Oil and Gas in Colorado and an Introduction to the Role of the Colorado Oil and Gas Commission

Colorado’s Oil and Gas Industry History

Colorado’s first commercial oil well was drilled in Florence, Colorado in 1881.[11] Colorado had ten of the country’s 100 largest natural gas fields and three of its 100 largest oil fields in 2014 due to the geology of the state and its location on top of the Niobrara shale formulation in the Denver-Julesburg Basin.[12] This makes the Front Range and northeastern Colorado rich in oil and gas.[13] The Piceance and San Juan are the other two major basins in Colorado.[14] As of 2014, eighty-seven percent of Colorado’s 52,556 active oil and gas wells were in six counties, with over 32,000 of those active wells located in Weld and Garfield counties alone.[15] As such, Colorado is the seventh-largest natural gas-producing state and its oil production has increased by forty percent since 2016.[16]

Wells can be drilled vertically, directionally, or horizontally.[17] With vertical wells, drilling can descend anywhere from 2,500 to 12,500 feet, depending on the formation. Directional drilling occurs when a drill is pointed in the direction drilling is desired; modern technology allows for the angle to be shifted or rotated.[18] Horizontal wells involve drilling to the formation and then branching off horizontally to extend throughout the formation and make more of the resource accessible from a single well.[19] While this allows for fewer wells in a given area, there is still risk of environmental harm, namely chemical pollution in water and earthquakes.[20] Moreover, millions of gallons of water can be used for a single oil or gas well, and, unlike other water usages, most of the water used for oil and gas production is non-recoverable.[21]

Oil and gas production can occur on both state and federal land. While there are roughly 4,700 oil and gas leases on federal land in Colorado that are managed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management,[22] the oil and gas leases regulated by the COGCC are mostly on land that is owned by the Colorado State Land Board.[23] As of May 2020, there were 1,216 active leases on trust land.[24]

The Health and Environmental Impacts of Oil and Gas Development

The climate is in crisis, and this is increasingly affecting all communities, but particularly, and more seriously, those closest to oil and gas development.[25] This is all the more relevant given the mounting evidence that the fossil fuel industry is one of the largest contributing parties to the climate crisis,[26] a crisis that is leading to more extreme and unpredictable weather, sea level risings, and population displacements.[27]

A recent study, titled the Carbon Majors, found “ninety carbon producers were responsible for almost two-thirds of all anthropogenic CO2 between 1751 and 2013.”[28] A subsequent study found that carbon and methane emissions traced to the ninety carbon producers contributed “nearly 50 percent of the rise in global average temperature, and around 30 percent of global sea-level rise since 1880.”[29] Also, organizations and many journalists have revealed that the fossil fuel industry had early knowledge of climate risks and opportunities to act on those risks but repeatedly failed to do so.[30] This information provides a “solid scientific and evidentiary basis for holding fossil fuel companies accountable for climate change.”[31] Next to vehicles and transportation, oil and gas development is one of the most significant sources of smog and greenhouse gases.[32]

Oil and gas development has impacts on public health as well as the environment. An Oxford study from 2019 showed that certain natural gas development, including hydraulic fracturing, “ha[s] been found to be associated with preterm birth, high-risk pregnancy, and possibly low birth weight; three types of asthma exacerbations; and nasal and sinus, migraine headache, fatigue, dermatologic, and other symptoms.”[33] It concluded by stating that in an era of climate change and with continued evidence of natural gas development having direct local and regional health impacts, regulations may not be enough to cause the health effects to entirely go away and further steps need to be taken.[34] In Colorado, there are particular concerns about high chemicals in individuals’ blood, particularly children who live close to a large number of oil and gas wells.[35]

Additionally, a report submitted to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment and released in October 2019 found that certain chemicals released during various stages of oil and gas production could exceed certain guidelines and create negative health risks.[36] In January of 2021, the state of Colorado released its Greenhouse Gas Reduction Roadmap, outlining the path it plans to take to reduce the state’s greenhouse gas emissions.[37] The roadmap identifies oil and gas development as one of the largest sources of emissions and highlighted as two of its key steps to “continue swift transition away from coal to renewable electricity” and to “make deep reductions in methane pollution from oil and gas development. . . .”[38]

Colorado’s Primary Regulating Body of Oil and Gas and its Recent Mission Change

The COGCC is the agency within the Department of Natural Resources tasked with the regulation of oil and gas in Colorado. Its mission states:

The mission of the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) is to regulate the development and production of the natural resources of oil and gas in the state of Colorado in a manner that protects public health, safety, welfare, the environment and wildlife resources. Our agency seeks to serve, solicit participation from, and maintain working relationships with all those having an interest in Colorado’s oil and gas natural resources.[39]

The COGCC works with the oil and gas industry to achieve a balance of interests for all those involved and concerned. Previously, the legislature charged the Commission to “[f]oster . . . the responsible, balanced development production, and utilization of the natural resources of oil and gas in the state of Colorado in a manner consistent with protection of public health, safety, and welfare, including protection of environment and wildlife resources[.]”[40] Colorado SB 19-181’s passage in April 2019 changed the mission of the agency to more greatly prioritize public health and environmental protection than before.[41] This alteration was not new, however. It came after Proposition 112—a previous initiative that would have increased the setback distance for new wells—was defeated in 2018.[42]

Senate Bill 19-181 was signed into law by Colorado Governor Jared Polis and does three key things to be explored in this Note: it prioritizes the protection of public health, safety, and the environment; increases local government control over oil and gas regulations and clarifies that local regulations may be more restrictive than the state’s; and changes the requirements for pooling, including requiring a greater number of mineral rights holders to give approval before drilling can begin.[43] Prioritizing public health and the environment are addressed through many avenues such as increased protections for wildlife, wellbore integrity rules to better protect groundwater, and creating the first map with the paths of flowlines in the state.[44] In addition to prioritizing public health and the environment, giving greater local control and accounting for better protections to individuals with mining rights are important steps in altering the way in which the oil and gas industry operates.

Though these rules and regulations are promising, the impetus for change may be ineffective when not paired consistently with enforcement mechanisms to drive protection for public health and the environment. While these steps bring with them a modicum of positive change, the state legislature should have done more to protect public health and the environment. The state legislature should have ensured that oil and gas production does not continue in an almost unaltered manner due to certain legal precedents and caveats and the nature of industry resistance to change.[45] The Colorado Energy Office’s climate and energy page clearly states: “Reducing greenhouse gas emissions and a statewide transition to clean energy are integral to preserving Colorado’s way of life[.]”[46] The same year SB 19-181 passed, the state legislature also passed House Bill 19-1261, “Climate Action Plan To Reduce Pollution,” which set goals for greenhouse gas emission reductions by the years 2025, 2030, and 2050.[47] The COGCC’s rule changes strike at a compromise between implementing the new mission and not requiring the oil and gas industry to bear an influx of countless environmentally-conscious regulations and requirements. Despite SB 19-181 being heralded as some of the most progressive oil and gas legislation yet to be enacted,[48] it leaves the COGCC with limited options to meaningfully pursue its new mission in a world that is changing priorities and keying in on public health and environmental protections.

- Three of SB 19-181’s Changes and how the COGCC’s Rules Implementing Them did not Capitalize on all Opportunities to Prioritize Public Health and the Environment

This Section will explore in more detail three major changes brought about by SB 19-181: the prioritization of public health and the environment, an increase in local government control, and the change in forced pooling. It will further explore the COGCC’s new rules implementing them, which became effective as of January 15, 2021.[49] At this time, nuances in the rules’ implementation have yet to be seen. Changes in other branches of the Colorado government and regulatory state may likewise leave ambiguities unresolved.

Prioritization of Public Health and the Environment

Elevating public health and the environment is an accomplishment, but without sufficient enforcement measures, SB 19-181 is more a paper tiger than environmental revolution. Oil and gas production are known to pollute the environment and contribute to climate change, and the amount produced seems to increase with each passing year.[50] Oil and gas production and processing are among the largest sources of industrial greenhouse gases in the United States, only behind coal-fired power plants.[51] To avoid the disastrous effects of climate change, emissions from the oil and gas industry will need to be addressed in substantial ways. While making this a priority for the COGCC and industry is helpful, the rules recently adopted by the COGCC only achieve change in small doses. Much will be left to the courts to establish the meaning of ambiguous language in its regulations. This may prove to be a risky endeavor in light of Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission v. Martinez, a case decided before SB 19-181 and the new mission, where the Colorado Supreme Court held that prioritizing the environment and public health remains a secondary consideration for the COGCC behind oil and gas development.[52] As the regulatory body for oil and gas development, it makes sense that the Commission’s priority would not be solely public health and the environment, as that would be more fitting for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Nonetheless, the Department of Public Health and Environment’s 2019 report on health impacts of oil and gas operations helped bring about the changes implemented by the COGCC and was heralded by some as a reinforcement of what is already known—“[w]e need to minimize emissions from oil and gas sources.”[53] Given the mounting evidence of the industry’s negative impacts, it would be appropriate for the COGCC to acknowledge the concerns and make an effort towards creating a solution through whatever means SB 19-181 allowed. As there were concerns expressed about SB 19-181 within the public health and environmental context, the COGCC must step up to advance and not hinder the mission of other agencies tasked with parallel secondary goals by creating regulations that enforce the new mandate.[54]

In addition to the mission change requiring the protection of public health and the environment, SB 19-181 does make other changes. Among them is a broader definition of the phrase “minimize adverse impacts,” now meaning “the extent necessary and reasonable to protect public health, safety, and welfare, the environment, and wildlife resources to: (a) Avoid adverse impacts from oil and gas operations; AND (b) Minimize and mitigate the extent and severity of those impacts that cannot be avoided.”[55] This new change entirely struck any consideration of cost-effectiveness. Also, the bill explicitly clarifies that the new mission neither alters nor negates the authorities of Colorado’s air quality control commission, water quality control commission, state board of health, or solid and hazardous waste commission to regulate their respective areas.[56] Furthermore, SB 19-181 adds this provision, requiring the COGCC to adopt rules that:

(i) Adopt an alternative location analysis process and specify criteria used to identify oil and gas locations and facilities proposed to be located near populated areas that will be subject to the alternative location analysis process; and

(ii) In consultation with the Department of Public Health and Environment, evaluate and address the potential cumulative impacts of oil and gas development.

(§ 34-60-106(11)(c)).[57]

As of November 2020, the COGCC had adopted its new mission and final rules implementing the directives of SB 19-181. However, the COGCC’s Statement of Basis, Specific Statutory Authority, and Purpose very clearly stated that SB 19-181 was not a mandate for the COGCC to create new regulations requiring the protection of biological resources.[58] Rather, the limited scope of the statute’s changes allowed the COGCC to maintain or strengthen many of its existing rules intended to protect biological resources, “but did not make significant changes to its approach to protecting biological resources.”[59] It would seem that despite the new mission for the COGCC, there is not an enforceable mandate by which the Commission must actively implement changes—in turn suggesting that only a limited transformation will be required in the immediate future for oil and gas operators.

To offer some hope, however, many of the most helpful rules in pushing forward the Commission’s new priorities are those in the 300 and 900 series.[60] The embodiment of the mission of SB 19-181 is primarily seen in Rule 301(a) and includes most of the language meant to be incorporated.[61] It states, the Director “will approve operations only if they protect and minimize adverse impacts to public health, safety, welfare, the environment, and wildlife resources, and protect against adverse environmental impacts on any air, water, soil, or biological resource resulting from Oil and Gas Operations.”[62] Having this information will aid the COGCC and the CDPHE in a cumulative impacts analysis.[63] The collection of this information will highlight more areas where operations can improve and hopefully nudge the industry into practices that preserve the environment more comprehensively.

Additionally, Rule 303.a(5)(b) includes the language for what an operator must include in a cumulative impact analysis:

“The Operator will submit a Form 2B, Cumulative Impacts Data Identification that provides quantitative and qualitative data to evaluate incremental adverse and beneficial contributions to cumulative impacts caused by Oil and Gas Operations associated with the proposed Oil and Gas Development Plan, including any measures the Operator will take to avoid, minimize, or mitigate any adverse impacts[.]”[64]

Resources to be considered include air, public health, water, terrestrial and aquatic wildlife and ecosystems, soil, and public welfare.[65] It should be noted that this provision only requires the data to be collected for the evaluation repository of these effects on cumulative impacts. The following rules set standards; for example, Rule 314 includes the language about what must be done to “address” cumulative impacts through Comprehensive Area Plans.[66]

For certain resources, however, the COGCC felt more information was needed prior to setting standards, offering no hard timeline for when a standard might be set beyond stating that it “may undergo additional rulemakings in the future should those evaluations indicate that additional regulations to address cumulative impacts are necessary.”[67] As the development of these plans is voluntary, although “encourage[d],” the COGCC’s intent to incentivize development of these plans is “by conveying an exclusive right to operate in the area covered by the CAP [Comprehensive Area Plan] for an appropriate duration of time.”[68] That time frame is six years.[69] Generally, an oil or gas well will produce for longer than twenty years.[70]

Additionally, Rule 304 requires an alternative location analysis if the working pad is—among other things—within 2,000 feet of one or more residential buildings or a school or child care, as well as within 1,500 feet of a designated outside activity area.[71] “The purpose of the alternative location analysis is to create a tool for the [COGCC] and the operator to use to identify the best location to avoid adverse impacts to public health, safety, welfare, the environment, and wildlife resources.”[72]

The COGCC 900 series is completely dedicated to providing guidance on preventing adverse environmental impacts.[73] These rules begin with general standards, allowing the COGCC Director to require certain actions by an Operator, though any mitigation or avoidance action is triggered only if the Director comes to be concerned.[74] To clarify, that means there is no set obligation that can be triggered objectively; the requirement to avoid or mitigate a negative impact depends on the Director’s discretion to decide if and what action should be taken. No later than January 2022—and occurring annually after—the Director will report to the Commission cumulative impacts data that include information regarding wildlife resources, air quality and greenhouse gas pollution reductions, new technologies that may “provide innovative methods to reduce emissions or otherwise avoid” cumulative impacts, and any future recommendations to address certain cumulative impacts.[75] However, a given operator’s participation in these studies evaluating cumulative impacts of oil and gas development is, again, not mandatory.[76] Considering not only the naturally ambiguous language here, but also the voluntary nature of certain important pieces that could have been mandated, certain protections will likely be at risk depending on their eventual interpretation by the courts. The gray areas of what is allowable or required and what is excessive or voluntary will likely result in a case-by-case analysis that will not provide guidance or environmental protection for years to come.

Lastly, much of the protections set in place by this new legislation do not apply retroactively to already-permitted or in-use wells, unless clearly identified.[77] When an existing oil and gas facility is changed or modified, the COGCC’s new rules may require an operator to retrofit existing equipment under the new standards.[78] It can be hoped that all facilities will update as needed, but there may be a danger that this requirement will cause operators to refrain from updating to avoid the time and cost required to abide by these new rules. Furthermore, the COGCC did not clearly list the operational rules that apply retroactively with the likely result that certain rules will not be followed, time will be wasted, or confusion will delay the rules’ practical application, detracting from the broader goals of this mission change. None of these are ideal.

Increased Local Government Control

The granting of greater local control is a step in allocating the responsibility of limiting the growth of oil and gas. Nevertheless, without a ratchet on the potential for growth of oil and gas development in all counties, there is a risk that the good achieved in certain localities with stricter regulations will either break even or fail to outweigh the harm caused by others seeking to promote as much oil and gas development as allowed by the new regulations.

In the context of local government control, SB 19-181 states that:

[T]he power and authority granted by this section does not limit any power or authority presently exercised or previously granted. Each local government within its respective jurisdiction has the authority to plan for and regulate the use of land by: . . . Regulating the use of land on the basis of the impact of the use on the community or surrounding areas; Regulating the surface impacts of oil and gas operations in a reasonable manner to address matters specified in this subsection (1)(h) and to protect and minimize adverse impacts to public health, safety, and welfare and the environment. [79]

Additionally, SB 19-181 removed an exception that previously existed, now allowing county boards to regulate oil and gas production for noise on both public and private properties.[80]

However, the strongest language is found entirely in its own section. As Rule 302 Local Control states, “Local governments and state agencies, including the commission and agencies listed in section 34-60-105 (1)(b), have regulatory authority over oil and gas development, including as specified in section 34-60-105 (1)(b). A local government’s regulations may be more protective or stricter than state requirements. (§ 34-60-131).”[81]

This essentially allows a county, municipality, or locality to pass its own regulations that are more restrictive on oil and gas development than the state’s, meaning, theoretically, a county or locality could make it more difficult for oil and gas development to take place at the rate it has been in the state.

The Colorado Constitution allows cities and towns to adopt a home rule charter.[82] A home rule state grants broad authority to localities, allowing them to regulate any local matters, with state law superseding a conflict only when the matter is of mixed or state concern.[83] The contrary system to this is Dillon’s Rule. Dillon’s Rule localities have a narrower interpretation of local governmental authority; they only have the powers to govern specifically sanctioned by the state government.[84] Natural gas extraction has generally been governed by state regulation, but as environmental concerns have increased—namely those related to groundwater—local bans or regulations on hydraulic fracturing have emerged.[85] Issues thus arise when “. . . home rule municipalities are granted authority to protect public health, safety, and welfare. However, state regulation or state interests in natural gas extraction may preempt a local ordinance banning frac[k]ing if an irreconcilable conflict exists between the two.”[86] SB 19-181 pacifies this issue to an extent, however, oil and gas production largely remains a state or mixed concern and therefore local regulations may be challenged depending on the larger impact they have on development across the state.

In addition to possible conflicts between state and local governments, there are also concerns about how regulations may vary across counties in Colorado. Possibly the best example of how diametrically opposed two regulatory approaches could be is already showcased in the neighboring counties of Boulder and Weld.[87] Boulder commissioners are seeking the “toughest regulations [they] can get” on oil and gas development, falling in stark contrast to Weld County, where, with nearly half of Colorado’s active wells, the county rejected a permitting moratorium and has taken steps to facilitate new oil and gas development.[88]

Senate Bill 19-181 affords local governments greater control. However, Boulder and Weld exemplify different interpretations of this. While Boulder seeks to be more protective of the environment, Weld’s attitude is one of “forc[ing] local control back down their throats” and using local control to welcome the oil and gas industry even more.[89]

Weld County’s minerals mostly rest beneath privately owned land, while Boulder County’s are almost exclusively beneath publicly owned open space, leaving Boulder officials to defend against new oil and gas drilling.[90] To showcase the vastly different approaches another way, the reported royalty revenues from oil and gas in Boulder County in 2018 were $224,103. In Weld County that same year they were $10,259,014.[91] Even simply taking a look at the oil and gas development webpages for the respective counties will showcase their polar approaches; Boulder’s reads: “Boulder County is committed to protecting our open space from oil and gas development to the greatest extent possible,” and the tone is decidedly health-minded, whereas Weld’s proudly states, “Weld County is the number one producer of oil and gas in the State. 87% of all crude oil production and 43% of all natural gas production in Colorado comes from Weld County!”[92]

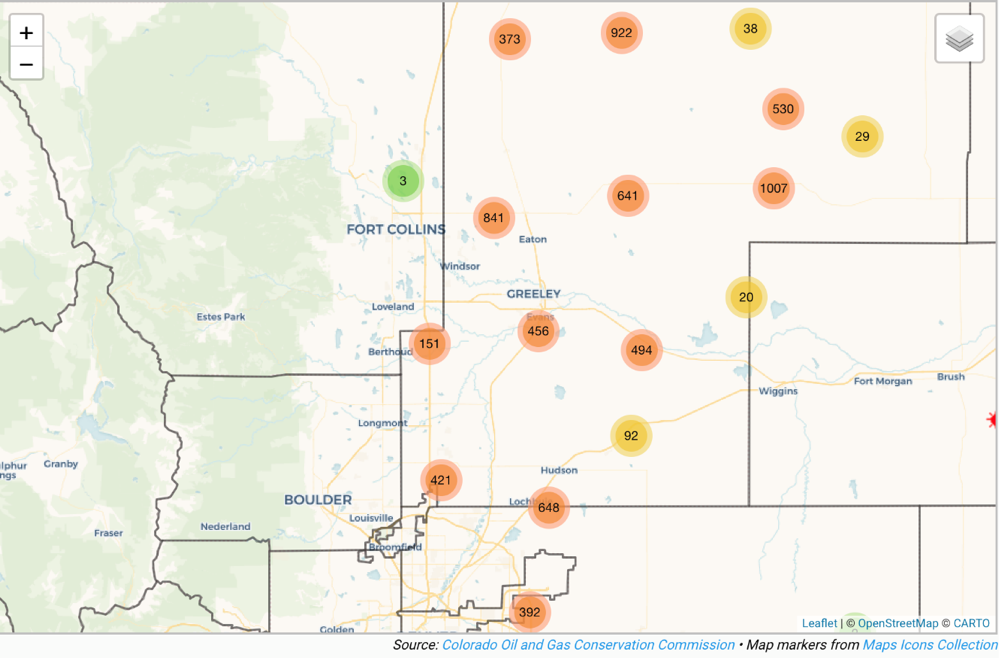

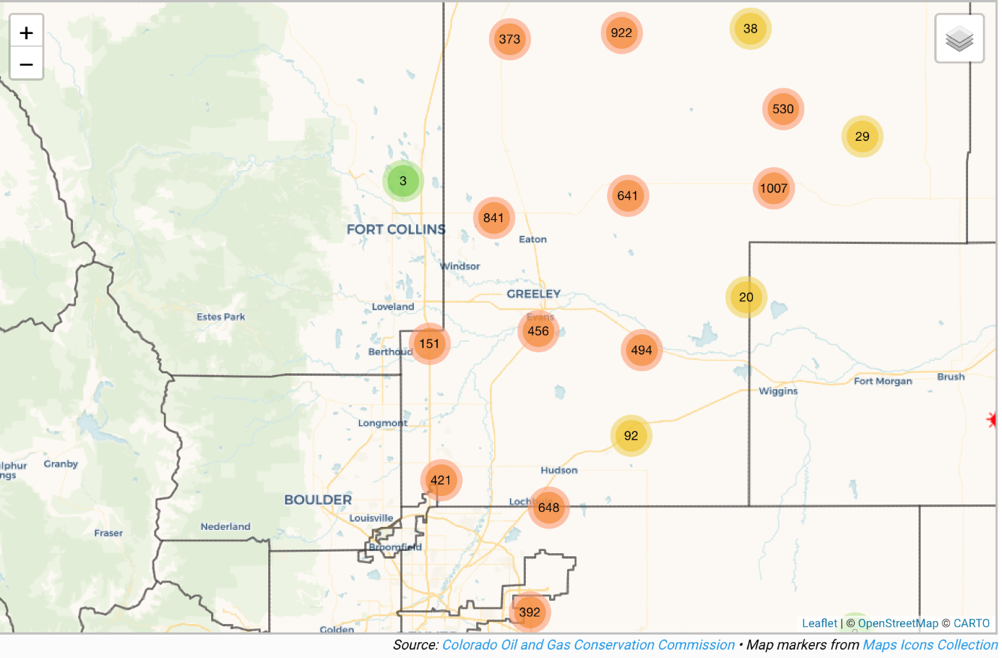

Perhaps nothing showcases the contrast of these neighboring counties better than a map.

Figure 1: The map shows the location of all pending and approved permits for oil and gas wells, limited to the northeastern part of the state as of mid-2020. [93]

Notice that there is not a single permit shown in Boulder County.

Boulder County has plans to take full advantage of the new authority granted to local governments by SB 19-181.[94] This is understandable given the moratorium Boulder adopted in 2019 on new oil and gas permits.[95] Boulder cited the oil and gas industry’s impact on air, water, soil, biological quality, and ecosystems, among a few others, as the reason for the moratorium.[96] This reasoning will sound similar to those familiar with Boulder County, which passed some of the strictest regulations in the state in 2017, and possibly the country, and has consistently monitored its air quality at the Boulder Reservoir specifically due to oil and gas development.[97] Additionally, since the COGCC passed the 2,000-foot setback requirement for new wells, the Boulder County Commissioners’ Office passed changes to its Land Codes requiring future oil and gas well pads generally to be 2,500 feet from homes, schools, and daycare facilities.[98]

Across a mere county border line, things could not be more different.

Although fossil fuel extraction in Weld County is as old as the County itself, in the last few years Weld County has experienced the biggest oil and gas boom in its history. . . . Energy companies are investing in new wells and infrastructure in Weld County to tap into the estimated oil and gas reserve of as much as 1 billion to 1.5 billion barrels of oil-equivalent in the Wattenberg Field. The production has translated into a boost for the local economy, job creation, and tens of millions of dollars in property taxes and severance taxes for local jurisdictions.[99]

Weld attributes a great deal of positive economic activities to the growth and development of oil and gas in its county and it is unsure how SB 19-181 will impact its future production.[100] In 2019, Weld opened “a first-in-Colorado local oil and gas department to process drilling permit applications and regulate well pads throughout the mineral-rich region” that was created with the intention to expedite development.[101] The expectation was for the new department to handle nearly 2,000 applications a year.[102] This expectation, though not shocking for the county, came after the passage of SB 19-181 and its new priorities. It was a move that provoked response from the COGCC and will likely lead to a stand-off of some sort between state regulation and the general increase of rights granted to local governments.[103]

However, if there is no incentive to have more restrictive regulations, why would a county do so? Senate Bill 19-181 makes public health and the environment a priority for the COGCC, but that mandate’s implementation may vary by local government unless public health and the environment are already priorities there, as seen in Boulder County.[104] Different regulations of oil and gas development create issues and have impacts irrespective of county borders.[105] With this being a tide-turning bill, a question arises of what should have been done to entice or motivate a local government to pass tougher restrictions on oil and gas development in counties such as Weld, where a dependence on the oil and gas industry exists.

Changes to Forced Pooling and Drilling Requirements

Ensuring greater protections for non-consenting mineral rights owners is a welcome change to ensure greater public health protections for those living outside areas where development is actively being slowed. Operators may apply to the COGCC to establish drillings units in a given area and then “pool” the interests of the surrounding mineral owners.[106] Pooling is the “consolidation of leased and unleased minerals to access one common underground mineral reserve.”[107] Owners of those mineral interests may participate in pooling voluntarily or operators may apply to the COGCC for permission to “force pool” nonconsenting owners.[108]

In this third major area of change, SB 19-181 amends and adds the following key language:

(b)(I) In the absence of voluntary pooling, the commission, upon the application of a person who owns, or has secured the consent of the owners of, more than forty-five percent of the mineral interests to be pooled, may enter an order pooling all interests in the drilling unit for the development and operation of the drilling unit. Mineral interests that are owned by a person who cannot be located through reasonable diligence are excluded from the calculation. . . .

(7)(a) Each pooling order must: . . .

(II) Determine the interest of each owner in the unit and provide that each consenting owner is entitled to receive, subject to royalty or similar obligations, the share of the production from the wells applicable to the owner’s interest in the wells and, unless the owner has agreed otherwise, a proportionate part of the nonconsenting owner’s share of the production until costs are recovered and that each nonconsenting owner is entitled to own and to receive the share of the production applicable to the owner’s interest in the unit after the consenting owners have recovered the nonconsenting owner’s share of the costs out of production;

(III) Specify that a nonconsenting owner is immune from liability for costs arising from spills, releases, damage, or injury resulting from oil and gas operations on the drilling unit; and

(IV) Prohibit the operator from using the surface owned by a nonconsenting owner without permission from the nonconsenting owner.[109]

Section 14 raises the royalty interest—or the percentage amount of production an owner may be paid—from 12.5 percent to thirteen percent for gas and sixteen percent for oil until the consenting owners have been fully reimbursed for their costs.[110] So, to distill this down, owners who might not want to have a well will not only be forced to allow the well and deal with the impacts of local drilling but will also lose out on their right to do with their mineral interest as they might wish.[111] For mineral interest owners that live nearby, their concerns of the side effects can be more acute if they are added on top of the stress of being forced to allow the drilling to commence. Concerns that homeowners express when oil and gas wells are suddenly in eyesight include water quality, sound and noise during development, and health impacts.[112]

The concern about a minority of consenting owners forcing the pooling of nonconsenting owners was reflected most significantly in Rule 506: Involuntary Pooling Applications. The rule states that an application for involuntary pooling may be filed by an owner who owns or secures more than forty-five percent of the mineral interests to be pooled within a specific drilling unit established by the COGCC.[113] However, the filing must be made no later than ninety days in advance of when the COGCC is set to hear the matter and there must be evidence provided that an offer was made to all owners to “lease or participate no less than 90 days prior to an involuntary pooling hearing.”[114] Simply put, the offer and the filing of involuntariness could be filed concurrently.

The COGCC did broaden how an individual would have standing to bring forward a proceeding. Previously, the COGCC’s rules were narrower than the standards put in place by the Colorado Administrative Procedure Act.[115] This expansion was done in large part to reflect the COGCC’s new recognition that “members of the public other than operators may be well-positioned to provide insight into potential public health, safety, welfare, environmental, and wildlife impacts of various Commission-approved actions” as well as to include local governments now that their participation in surface impacts has been increased.[116]

The new Rule 507 states that any “person who may be adversely affected or aggrieved by an application may submit a petition to the Commission as an Affected Person to participate formally as a party in an adjudicatory proceeding,” and that their petition must:

- Identify an interest in the activity that is adversely affected by the proposed activity;

- Allege such interest could be an injury-in-fact if the application is granted;

- Demonstrate that the injury alleged is not common to members of the general public.[117]

Though the language in Part C is common, the COGCC did clarify that impacts on the environment, like climate change, “might be considered to be held in common by the general public under Rule 507.a.(3).C, [therefore] the Commission clarified in Rule 507.a.(4).D that a person with a unique interest in a natural resource or wildlife may be considered an affected person based on impacts to the natural resource or wildlife that the person uses or enjoys.”[118]

On the other hand, surface owners are given only a short window to voice concern if they are not already aware of plans nearby. Under Rule 412, operators have a duty to notify surface owners only thirty days prior to operations beginning.[119] The COGCC did expand the geographic area where notice is required to the entirety of the 2,000-foot buffer zone around the working pad. “Providing notice to a wider radius is more consistent with the purpose of the Rule, because it better communicates to nearby surface owners and residents what is happening on the site.”[120]

Here, the COGCC managed to put into formal rules the most straightforward and meaningful language, in contrast to the previous other sections. While it has yet to be seen what will be accomplished through this increase in the pooling number requirement or the greater access to the Commission itself, there is some room for hope that this will inspire the COGCC, and in turn, the oil and gas industry, to take the mandate of SB 19-181 seriously and implement it in functional and meaningful ways.

- A Legal Analysis of SB 19-181 and the COGCC’s Implementation of it: Some Strengthened Protections, Yet Significant Remaining Gaps

Despite the passage of the COGCC’s rules implementing SB 19-181, the work is not complete. Given the less than precise language some of the rules offer and the weight of decades of industry legislation and common law interpretation, the courts will be the next battleground to see if protecting public health and the environment truly perseveres as a new pillar of the oil and gas industry in Colorado.

Prioritization of Public Health and the Environment

Perhaps the best place to begin is with the case Martinez v. Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, where the Colorado Court of Appeals held in 2017 that the Oil and Gas Conservation Act’s inclusion of the phrase “ ‘to the extent necessary to protect public health, safety, and welfare,’ when describing the purpose of regulation, evidence[d] a similar intent to elevate the importance of public health, safety, and welfare above a mere balancing,” but rather a priority that regulation is subject to.[121] However, in 2019, the Colorado Supreme Court overturned the previous decision in Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission v. Martinez:

[The] proposed rule would have precluded new oil and gas development unless it could occur ‘in a manner that does not cumulatively, with other actions, impair Colorado’s atmosphere, water, wildlife, and land resources, does not adversely impact human health, and does not contribute to climate change.’ In light of our [construction of the] Act, we conclude that the Commission correctly determined that it could not, consistent with those provisions, adopt such a rule. Specifically, as set forth above, we do not believe that the pertinent provisions of the Act allow the Commission to condition one legislative priority (here, oil and gas development) on another (here, the protection of public health and the environment).[122]

The Martinez case dealt with a rule proposed by the respondents that would keep the COGCC from issuing any permits “unless the best available science demonstrates, and an independent, third-party organization confirms, that drilling can occur in a manner that does not cumulatively, with other actions, impair Colorado’s atmosphere, water, wildlife, and land resources, does not adversely impact human health, and does not contribute to climate change.”[123] They gathered public comments, but the COGCC refused to engage in a rule-making process for the proposed rule. Though a split appellate court found in favor of the respondents, the Colorado Supreme Court said, among other things, that the COGCC was correct to decline.[124] The court said this is because the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Act (the “Act”)—which created and guides the COGCC—states, “the pertinent provisions do not allow it to condition all new oil and gas development on a finding of no cumulative adverse impacts to public health and the environment.”[125]

Although this decision came down before the passage of SB 19-181 and the new COGCC rules, the Martinez case highlights the difficulty facing meaningful prioritization of public health and the environment moving forward when the state benefits from oil and gas production and the COGCC is fundamentally responsible for regulating the industry, without which the COGCC would be unneeded. Before turning to recent case law, note that the Act declares:

It is the intent and purpose of this article 60 to permit each oil and gas pool in Colorado to produce up to its maximum efficient rate of production, subject to the protection of public health, safety, and welfare, the environment, and wildlife resources and the prevention of waste as set forth in section 34-60-106(2.5) and (3)(a), and subject further to the enforcement and protection of the coequal and correlative rights of the owners and producers of a common source of oil and gas, so that each common owner and producer may obtain a just and equitable share of production from the common source.[126]

The Act reiterates that the purpose remains production of oil and gas in Colorado, subject to protecting public health and the environment.

Similarly, the Northern Front Range has been out of compliance for National Ambient Air Quality Standards since 2007.[127] It was only in 2012 when setbacks were extended to 500 feet from residential homes and 1,000 feet from high occupancy buildings.[128] That year the Denver-Julesburg Basin had a population close to 2 million people and also saw an increase of active oil and gas wells by ninety-three percent from 2000.[129] It was estimated that nineteen percent of the population at that time lived within one mile of a well, and the greatest rates of growth were in the buffer areas greater than or equal to 350 feet and less than 350 to 500 feet, where the population more than doubled in that same time frame.[130]

A study conducted in 2016 looked at natural gas setbacks in Texas, Pennsylvania, and Colorado and the health risk posed by air pollution. It found that pathways of pollution included the release of volatile organic compounds during drilling, leaks at connection points, heavy diesel equipment used, chemical mixtures used to aid extraction, and the risk of blowouts and other explosions.[131] It concluded that more significant setback distances (Colorado had not yet passed its 2,000-foot setback) would be a prudent and encouraged mitigation step; however, distance alone was not significant and more mitigations steps and technologies should be implemented at every opportunity.[132]

Lastly, a federal court ruled in July of 2020 that northern Weld County—an area with heavy emissions—should be included in the Denver metro area for purposes of its air pollution measurement limits.[133] This will likely increase pressure on the oil and gas industry there to operate differently and may suggest that their current practices pose an even more dire risk to public health than previously thought. At the close of 2019, the Colorado Air Quality Control Commission passed new rules that included a twice-a-year leak detection requirement at well facilities that emit over two tons of volatile organic chemicals a year, a monthly/quarterly leak detection requirement for sites within 1,000 feet of occupied buildings, and a comprehensive annual emissions report requirement for all oil and gas facilities.[134] Yet, this still has not ensured a lack of air pollution across the Front Range and especially not for those closest to these facilities.

For more than fifteen years, Colorado has flunked federal air quality health standards with ozone air pollution exceeding a decade-old federal limit of seventy-five parts per billion, which was tightened to seventy parts per billion under President Barack Obama.[135] The World Health Organization recommends no more than fifty parts per billion to protect human health.[136] The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in December 2020 reclassified Colorado as a “serious” violator of federal air quality laws, forcing Colorado to take more serious steps to reduce air pollution.[137] State air quality commissioners were “expected to approve tighter regulations for the oil and gas industry, a source of the volatile organic chemicals that contribute to the formation of ozone.”[138] Yet as of April 8, 2021, WildEarth Guardians sued the EPA for failing to take “timely action” to ensure the Denver area meets these federal standards, “effectively denying clean air for the Denver Metro-North Front Range region.”[139]

In January 2021, Colorado released its “Greenhouse Gas Pollution Reduction Roadmap.”[140] “The Roadmap represents the most action-oriented, ambitious and substantive planning process that Colorado has ever undertaken on climate leadership, pollution reduction and a clean energy transition” and lays out ways to achieve the state’s climate goals that include reducing emissions in five key areas, one being oil and gas development.[141] The COGCC’s role will be limited due to the control of the state’s air quality control commission, but its primary contributions are prohibiting routine flaring and requiring that:

[A]ll new oil and gas development plans…provide detailed information regarding greenhouse gas emissions associated with proposed oil and gas development as well as cumulative impact plans detailing how these emissions will be avoided and minimized. The COGCC will be responsible for determining if permit applications avoid and minimize impacts to public health and the environment.[142]

What remains to be seen is if the COGCC takes the necessary steps to make these permitting decisions responsibly with its focus on the priority of public health and the environment, not the continuation of oil and gas development as it has been.

Increased Local Government Control

SB 19-181’s only limitations on local regulatory powers are that these powers must be exercised in a “reasonable manner” and any regulations imposed on the industry must be “necessary and reasonable” to protect public health and the environment—limitations that are undefined and have yet to be tested in full by the courts.[143] However, two cases may offer a glimpse into what the future will hold.

In the sister cases of City of Longmont v. Colorado Oil & Gas Association and City of Fort Collins v. Colorado Oil & Gas Association, the Colorado Supreme Court again found for the oil and gas industry, though indirectly through the COGCC. Longmont had banned fracking and the storage and disposal of its waste and Fort Collins had instituted a five-year moratorium on fracking and storage.[144] The question presented was whether these municipalities could take these actions or if state law preempted these actions. The court, in looking at the Act and the COGCC rules that guide the state’s control over fracking, was convinced that the state’s interest in the responsible development of oil and gas resources includes a strong interest in the uniform regulation of fracking.[145]

The court said that when there is a mixed state and local concern, state law will supersede a conflicting ordinance, even if the language is not explicit.[146] As the state is interested in the “efficient and fair” development of oil and gas, these bans implicated this interest in addition to the fact that they would have increased the cost of production and reduced royalties.[147] The court also raised an interesting, though not unforeseen argument: “Longmont’s fracking ban may create a ‘ripple effect’ across the state by encouraging other municipalities to enact their own fracking bans, which could ultimately result in a de facto statewide ban.”[148]

That same day, the court went on to state something else of note in the Fort Collins case:

As we observed in Longmont, however, the availability of alternatives to fracking does not lessen the state’s above-described interest in fracking. Nor do such alternatives alter the fact, found by the district court, that ‘virtually all oil and gas wells’ in Colorado are fracked. Thus, even though it may be possible to produce oil and gas without fracking while the moratorium is in effect, the moratorium interferes with the many operators who have determined that fracking is necessary to ensure productive recovery.[149]

There is industry concern that granting more control to local governments will result in a patchwork scheme. Although this may increase difficulties for companies producing in more than one county, a slower rate of development is likely welcome by local citizens who do not wish to have oil and gas production nearby. In addition, a slower rate of development is arguably an ideal embodiment of a manageable way to prioritize and protect the public health and environment over maximum development.

Consider a more recent and relevant example from 2020 in the case of Our Health, Our Future, Our Longmont v. State.[150] The Boulder District Court states: “[c]onsidering the relative interests of the state and Longmont in regulating fracking, considering the totality of the circumstances, and finding guidance in the supreme court’s reasoning in Longmont, this Court finds that fracking is a matter of mixed state and local concern.”[151] Furthermore, the court points out, “[t]he Commission, as made obvious by the plain language of the Act, retains the singular authority to regulate subsurface oil and gas activity.”[152] This suggests that despite the broader authority now granted to local governments under SB 19-181, courts may find it more prudent to stay aligned with previous jurisprudence that exhibited deference toward allowing oil and gas development. As a well-worded example:

[D]espite that SB 19-181 added a provision that local governments may regulate surface impacts of oil and gas operations and specifically listed ‘land use’ among the matters a local government can regulate, the addition of ‘land use’ in SB 19-181 without more substantive changes to the statutory scheme, does not alone demonstrate that SB 19-181 authorizes local governments to prohibit subsurface oil and gas development.[153]

This case came down at the end of 2020 and upholds the above findings in Longmont and Fort Collins, even in light of SB 19-181, as the courts seek to still abide by the previous state scheme to promote oil and gas production. The holding in favor of development despite local regulation is not inherently incorrect; it simply highlights the great difficulty that lies in front of local governments to not only craft regulations that fit within the bounds of their new authority, but to try and convince the state’s judicial system to change course in how it views the regulation of the oil and gas industry. Our Health, Our Future, Our Longmont underlines that the COGCC remains the party with the ability to regulate subsurface activities and curtail oil and gas development if desired, meaning the granting of local control over land use will likely end up more as a token than a tool. In particular, this will be the case if the courts find that certain limitations fall outside of the “necessary and reasonable” language that caveats the grant of increased local authority over oil and gas development. Questions remain to be answered about whether increased setbacks are reasonable due to noise and pollution concerns and whether location limitations are necessary for public health and environmental concerns. If the courts continue to find that surface regulation leads to the prohibition of subsurface oil and gas development,[154] local governments may be forced to get creative in ways to make development uneconomic.

Changes to Forced Pooling and Drilling Requirements

The history surrounding subsurface minerals and the extractive activities associated with them are long and convoluted. The regulations of these activities are certainly deferential to development and industry, with the concept of mineral estate dominance coming from both English common law and Mexican law.[155]

In the case of Gerrity Oil & Gas Corp. v. Magness, a suit for trespass and negligence was brought against an operator for his use of the surface. The Supreme Court of Colorado said:

Because the scope of a mineral rights holder’s implied easement is defined in terms of reasonableness and necessity, the reasonableness of the holder’s conduct is not only relevant, but is essential to any resolution of a trespass claim. Until it is found that the lessee’s conduct was not reasonable and necessary for the exploration or extraction of the minerals, a cause of action for trespass must fail.[156]

It likewise held that even violating COGCC rules could be valid, but not conclusive, evidence that the contract with the surface owner was breached.[157]

In the ongoing case of Wildgrass Oil & Gas Committee v. Colorado, a homeowner’s advocacy group is challenging Colorado’s forced pooling statute.[158] The crux of the case is that the COGCC granted a forced pooling application after the Wildgrass Oil and Gas Committee repeatedly raised concerns about health, safety, and the environment, and despite the Operator lacking the required thirteen percent (all that was required at the time) of leases of the relevant mineral interests for the area.[159] The case has been heard at both the state and federal level and is currently on appeal to the Tenth Circuit, where the plaintiffs are claiming constitutionality issues with the forced pooling practice.[160] In the original complaint, SB 19-181 was cited repeatedly.[161]

The COGCC’s Rule 511 allows for local public hearings to “gather feedback from a local community,” but the Commission has the discretion to decline.[162] “The Commission intends for its proceedings, including hearing processes, to be transparent, publicly accessible, broadly noticed, and to provide an opportunity for any person who may be impacted to participate.”[163] Whether this tool will be used has yet to be seen. It seems a public hearing may only go so far if, even after SB 19-181, the COGCC remains focused on regulating continued oil and gas development and not the individuals who come forward with concerns about their health in addition to the reality of operation being loud and unpleasant for many living nearby.[164]

In line with the modification of pooling interests, another consideration is environmental and distributive justice, which is tied to anti-development advocates. The COGCC should have considered who owns the mineral rights and who is facing the impacts of oil and gas development. This ultimately connects the first section of prioritizing the public health to the more functional changes made to forced pooling.

Colorado, as a split estate system, allows mineral owners a right of access to the surface property to extract their subsurface property. A split estate means the surface rights to a piece of land and the subsurface rights (such as the rights to develop minerals) are owned by different parties, and it is often the case that the mineral rights take precedence over other rights.[165] Those who reside on split estates (renters for example) may feel they have less decision-making power, thus causing them to be disenfranchised about surface activities near their homes that extract oil and gas beneath the homes. They may also bear more risks than benefits from the extraction, as their rights are often secondary to that of the mineral rights owner.[166]

A matter of constant litigation, the root question is often how much the surface is allowed to be used for development. One of two perspectives is the accommodation doctrine, which is adopted in Colorado:

The doctrine provides some relief to the surface owner inasmuch as the mineral lessee must respect, as far as is practical, the surface owner’s uses and not lay waste to the property. Examples include specified distances from drill sites to buildings, restrictions on use of water from the property, and location and depth of pipelines. The burden of proof in using the accommodation doctrine is on the surface owner. There must be an existing use or planned use of the surface.[167]

This means that a surface owner with no definitive plans for their surface use could find any hoped-for use gone or unable to be realized, let alone implemented, until the extraction of all that lies below is complete. To put that in perspective, “[i]n the [Denver-Julesburg Basin], [Piceance Basin], and [San Juan Basin], 57%, 36%, and 51%, respectively, of O&G wells drilled between 2000 and 2012 were located on a split estate where the surface land owner did not own the O&G beneath the surface.”[168] Until January 2021, most of them were likely unable to bring a cause of action in front of the COGCC. This may continue to be the case.

The COGCC’s new rules brought about several positives, with the 2,000-foot setback, a ban on routine venting and flaring of natural gas, and some protections for the environment and wildlife. Additionally, SB 19-181 does shift the balance of considerations moving forward to the “regulation” of oil and gas in a manner that prioritizes public health and the environment, rather than just “fostering” the industry.[169] Likewise, the wellbore integrity rules are heralded as the strongest in the county and are meant to protect groundwater from contamination by requiring annual testing.[170]

But SB 19-181 and the COGCC’s implementation of it are far from perfect, for exceptions and failed opportunities still plague the new era. Executive Director of Colorado Rising, Joe Salazar, said, “I think the oil and gas industry was able to place some loopholes in some of these rules [and] [w]hat it’s going to end up being is us fighting it out in front of the COGCC as well as in court to have some of these things interpreted according to Senate Bill 181.”[171] Colorado and the COGCC seem to have adopted an ingratiating bill and offered a few carrots, but still failed to incentivize change, prohibit a continued massive scale of oil and gas production, and urgently protect the public health and environment.

State-Level Changes, Implemented by SB 19-181

One simple change could have occurred in the state legislature that would have had dramatic potential. In the Act, Section 34-60-102 could have been rewritten to say: “It is the intent and purpose of this article to permit each oil and gas pool in Colorado to produce up to its maximum [at an] efficient rate of production, subject to the prevention of waste, consistent with the protection of public health, safety, and welfare, including protection of the environment and wildlife resources. . . .” Had this been done, there could have been more avenues pursued that would legitimately and concretely protect the public’s health and the environment. For example, it might force development to slow down and reevaluate its priorities or goals moving forward.

By removing the idea that an oil or gas pool should produce at a maximum rate, the state legislature could have allowed the COGCC to shift its focus to regulating and producing in a manner that is responsive to the needs of Colorado residents rather than at an optimal extraction rate that drains oil as quickly as possible. Other changes that could have been made include mandating participation in alternative location analyses rather than making it optional, mandatory engagement in cumulative impact and environmental studies, and longer periods of notice before development activities are set to begin. Doing so would have set a tone that the oil and gas industry is indeed prioritizing the public health and environment and making informed decisions, not barreling ahead as if the climate is not in crisis. Yet those steps were overlooked or negated to ensure that the oil and gas industry remained relatively stable and the backlash manageable.[172]

Similarly, had the Colorado legislature taken a stronger stance on environmental protection by completely altering the mission of its regulating body, the disruption of the industry could have been more significant. While some legislators may have found that SB 19-181 was a decent balance, the science strongly suggests less drilling would be an overall positive. However, given that the oil and gas contribution to the state’s GPD hovers around three percent, or nearly 13.5 billion dollars,[173] its influence may seem less powerful when considering that Colorado’s GDP is upwards of 350 billion dollars.[174] Moreover, part of the oil and gas industry’s impact comes from property taxes, a burden that could be taken on by another party. In light of this, it should be asked if the Colorado legislature did the best with what they had when they passed SB 19-181, or if there were ways to reframe the focus of the COGCC to better address the nature of oil and gas’s future.

The state of Colorado clearly has concerns about the environmental and health impacts of oil and gas, as demonstrated by the passage of SB 19-181 and the release of the GHG Roadmap in 2021. What has yet to be seen is if this bill will be able to meaningfully affect the change the legislature suggests it wants to address, or if it will fall short of producing at its maximum.

Regulator Changes, Implemented by the COGCC

The COGCC is placed in a difficult position of needing to regulate an industry that actively impacts the public health and environment. It is doing so but could certainly do better. One concrete example, which does not require writing out the “at a maximum efficient rate of production” in the mission statement for the COGCC, would be to acknowledge the likely waning impact of oil and gas in the state and take active steps to prepare for that. This action would ensure that no Operator, employee, county, or other actor is caught off guard or left without proper support. Looking at oil and gas well depletion and the number of new wells that would need to be added each month to keep production stable,[175] the industry seems to require an increase in production that does not appear likely to occur, let alone in a society that is becoming more aware of the climate impacts of oil and gas and seeking recourse for those harms.[176]

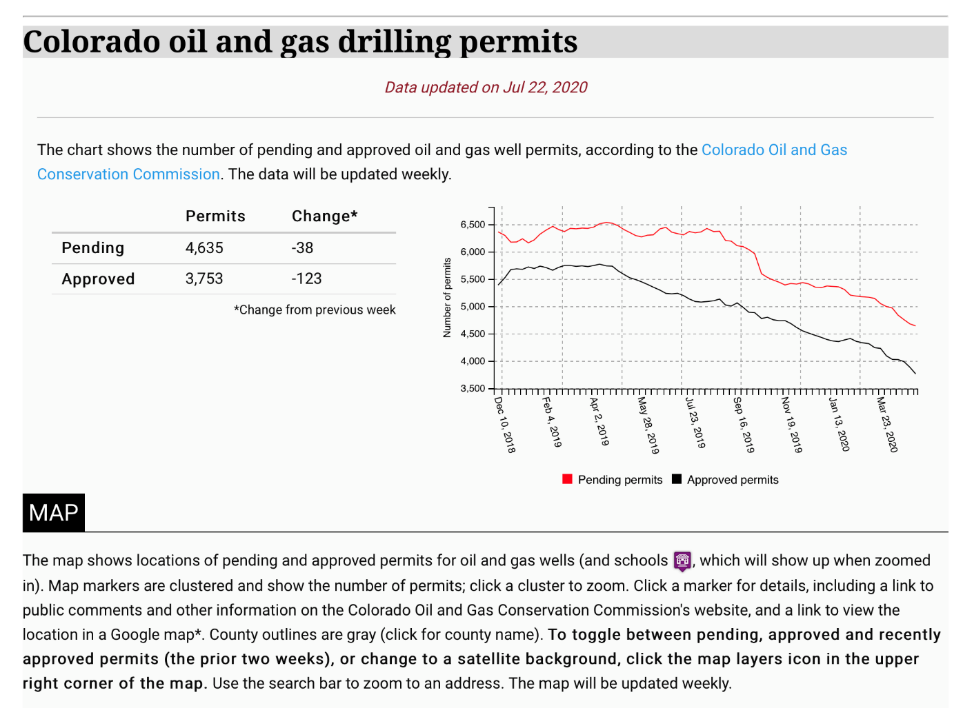

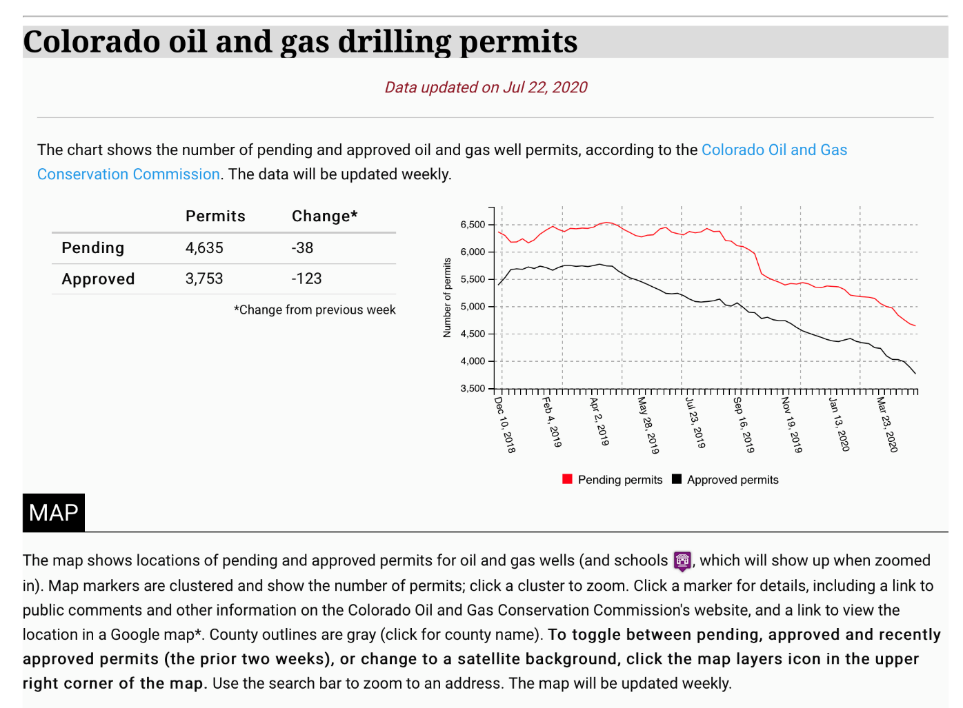

Figure 2:The chart shows the number of pending and approved oil and gas well permits, according to the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission as of July 22, 2020. [177]

Even before the unprecedented year of 2020 and its global pandemic, the number of drilling permits was falling, as shown by the figure above. More importantly, given the new mission of the COGCC to prioritize public health and the environment, actively encouraging an increase in the number of permits being issued and wells being completed seems counter to that same mission, unless production and operation are to remain as unchanged as possible. But as seen in Martinez, the COGCC cannot condition one legislative priority (oil and gas development) on another (the protection of public health and the environment).[178]

At the state level, the COGCC should institute more stipulations and measures to force companies and operators to take the new priorities seriously, rather than resorting to fines to slap them on the wrist when they fail to do so. Erin Martinez, Mark Martinez’s wife and Irwin’s sister, spoke to the COGCC at one point after the accident and said, “[n]othing has gotten easier and if anything time has only intensified our pain. . . . It is difficult to wrap your mind around the fact that a fine is the only recourse when such devastation and tragedy was the result.”[179]

Fundamentally, fines may not be the most effective means of actively seeking to protect public health and the environment. There is a significant consolidation of oil and gas companies. The fine levied in light of the Firestone accident was on Kerr McGee, a subsidiary of Anadarko Petroleum at the time of the accident. However, Anadarko was bought out by Occidental Petroleum Corp in 2019.[180] Noble Energy, a large player in the Denver-Julesburg Basin with roughly 120 wells in Weld County,[181] was recently purchased by Chevron for five billion dollars.[182] Both of the companies have a history of paying heavy fines for violating environmental regulations.[183] So while fines are one tool, they often do not deter to a desirable extent. This is due to the make-up of these large corporations, the lack of personal culpability, and the tendency for cases not to proceed to completion through the judicial system.[184]

Lastly, the COGCC must not skirt its duties to the people that make up the oil and gas industry and should consider protections for those whose livelihoods depend on an industry that is facing decline. Although not mandated by the Act, it is arguable that the people who work the oil and gas wells in Colorado are the Commission’s responsibility too, and it should work to see that they do not become disenfranchised as an externality if or when the industry seems unlikely to make a comeback to its peak. Colorado has an Office of Just Transition that handles the displacement of former coal workers.[185] The office was tasked with a “moral commitment,” and the COGCC should take upon itself the responsibility for those engaged in working in oil and gas and promote a cognizant and self-aware plan for the decades moving forward.[186] Within the realm of prioritizing public health and the environment, though not a direct focus of SB 19-181, the people who have worked in this industry, who have given their health and life to it, should have been a consideration in the implementing rules to ensure their well-being was protected. The COGCC and the state need to move forward and be responsible stewards for the people who make up this industry, not just the companies that add change to the state’s pockets.

Colorado is leading the way with oil and gas regulation, but it should not stop where it did. Senate Bill 19-181 was a great start to more severely regulating oil and gas and leaning into a future without fossil fuels, but more must be done. The state legislature needs to further provide avenues for the COGCC to ensure that accidents, disasters, and severe pollution stop occurring, while also limiting the negative impacts that oil and gas development have locally on the public health and environment in the short term.

The environment is not going to improve on its own. Tangible priorities need to be enforced and strong steps need to be taken by the relevant parties—such as the oil and gas industry—and they must be held accountable for their role in the climate crisis. For the sake of not only future generations and those affected by disasters, but those living next door to these operations today, public health and the environment need to be a front and center priority of legislators, regulators, and operators moving forward as the transition away from oil and gas takes hold.

- *Lauren Davis is a J.D. candidate at Colorado Law. ↑

- Sam Brasch, Colorado Announces $18.25 Million Fine For 2017’s Deadly Firestone Explosion, Colo. Pub. Radio (Mar. 12, 2020), https://www.cpr.org/2020/03/12/colorado-firestone-explosion-fine-oil-and-gas-commission/. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Robert Garrison, Colorado Oil and Gas Commission Levies Largest Ever Penalty for Firestone Explosion, Denver Channel (Apr. 13, 2020), https://www.thedenverchannel.com/news/local-news/colorado-oil-and-gas-commission-levies-largest-ever-penalty-for-firestone-explosion. ↑

- Brasch, supra note 1. ↑

- Daniel Glick & Jason Plautz, The Rising Risks of the West’s Latest Gas Boom, High Country News (Oct. 19, 2018), https://www.hcn.org/issues/50.18/energy-industry-how-site-workers-and-firefighters-responding-to-a-2017-natural-gas-explosion-in-windsor-colorado-narrowly-avoided-disaster. ↑

- Environmental Impacts of Natural Gas, Union of Concerned Scientists (June 19, 2014), https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/environmental-impacts-natural-gas. ↑

- SB 19-181: Protect Public Welfare Oil And Gas Operations, Colo. Gen. Assembly, https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb19-181 (last visited Oct. 17, 2021). ↑

- Garrison, supra note 3. ↑

- Colorado’s Sweeping Oil and Gas Law: One Year Later, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP (Apr. 30, 2020), https://www.gibsondunn.com/colorados-sweeping-oil-and-gas-law-one-year-later/. ↑

- Debra K. Higley & Dave O. Cox, Petroleum Systems and Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas in the Denver Basin Province, Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming, ch. 2, at 1 (U.S. Geological Survey Digital Data Series DDS–69–P 2007), https://pubs.usgs.gov/dds/dds-069/dds-069-p/REPORTS/69_P_CH_2.pdf. ↑

- Cary Weiner, Oil and Gas Development in Colorado: Fact Sheet No. 10.639, (Colo. State Univ. 2014), https://mountainscholar.org/bitstream/handle/10217/185140/AEXT_106392014.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y; Niobrara Shale Overview, Shale Experts, https://www.shaleexperts.com/plays/niobrara-shale/Overview (last visited Mar. 10, 2021). ↑

- See Weiner, supra note 11. ↑

- Lisa M. McKenzie, et al., Population Size, Growth, and Environmental Justice Near Oil and Gas Wells in Colorado, 50 Env’t Sci. & Tech., 11471, 11471 (2016), https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/acs.est.6b04391. ↑

- Weiner, supra note 11. ↑

- Colorado State Energy Profile, U.S. Energy Info. Admin., https://www.eia.gov/state/?sid=CO (last visited Mar. 18, 2021). ↑

- Weiner, supra note 11. ↑

- How Does Directional Drilling Work?, Rigzone, https://www.rigzone.com/training/insight.asp?insight_id=295 (last visited Apr. 4, 2021). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Johannes Fink, Hydraulic Fracturing Chemicals and Fluids Technology 259–329 (Gulf Professional Publishing 2d ed. 2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-822071-9.00027-X; Oil and Petroleum Products Explained: Oil and the Environment, U.S. Energy Info. Admin. (July 20, 2021), https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/oil-and-petroleum-products/oil-and-the-environment.php. ↑

- Union of Concerned Scientists, supra note 6. ↑

- BLM Colorado Oil and Gas, Bureau Of Land Mgmt., https://www.blm.gov/programs/energy-and-minerals/oil-and-gas/about/colorado (last visited Apr. 14, 2021). ↑

- Oil and Gas, Colo. State Land Bd., https://slb.colorado.gov/lease/oil-gas (last visited Mar. 18, 2021). ↑

- Judith Kohler, Oil, Gas Companies Not Alone: Mineral Rights Owners Facing Squeeze from Industry Downturn, Denver Post (May 28, 2020), https://www.denverpost.com/2020/05/28/colorado-mineral-rights-oil-gas/. ↑

- Tim Donaghy & Charlie Jiang, Fossil Fuel Racism: How Phasing Out Oil, Gas, and Coal Can Protect Communities, GreenPeace 1 (Apr. 13, 2021), www.greenpeace.org/usa/fossil-fuel-racism. ↑

- Joceyln Timperley, Who is Really to Blame for Climate Change?, BBC (June 18, 2020), https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200618-climate-change-who-is-to-blame-and-why-does-it-matter. ↑

- Tim Gaynor, ‘Climate Change is the Defining Crisis of our Time and it Particularly Impacts the Displaced’, U.N. High Comm’r for Refugees (Nov. 30. 2020), https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/latest/2020/11/5fbf73384/climate-change-defining-crisis-time-particularly-impacts-displaced.html. ↑

- Kristin Casper, Climate Justice: Holding Governments and Business Accountable for the Climate Crisis, 113 Am. Soc. of Int’l L. 197, 199–200 (2019), https://www.proquest.com/docview/2331307195/fulltext/1FC1C4874AD54DA3PQ/1?accountid=14503. ↑

- Id. at 200. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Judith Kohler, Colorado has New, Stronger Oil and Gas Regulations. Now What?, Denver Post (Apr. 24, 2019), https://www.denverpost.com/2019/04/24/colorado-regulators-new-rules-oil-gas/. ↑

- Irena Gorski & Brian Schwartz, Environmental Health Concerns From Unconventional Natural Gas Development, Oxford Rsch. Encyclopedia of Glob. Pub. Health (Feb. 25, 2019), https://oxfordre.com/publichealth/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.001.0001/acrefore-9780190632366-e-44. ↑

- Id. ↑

- See Jennifer L. Kovaleski, Erie Mom Concerned About Benzene Found in Son’s Blood, Denver Channel (Apr. 30, 2018), https://www.thedenverchannel.com/news/local-news/erie-mom-concerned-about-benzene-found-in-sons-blood. ↑

- ICF Int’l, Final Report: Human Health Risk Assessment for Oil & Gas Operations in Colorado 120 (Oct. 17, 2019), https://www.fcgov.com/oilandgas/files/20191017-cdphe-healthimpactsstudy.pdf. ↑

- Exec. Off. of Governor Jared Polis, Colorado Greenhouse Gas Pollution Reduction Roadmap (2021) [hereinafter COGHG Roadmap]. ↑

- GHG Pollution Reduction Roadmap, Colo. Energy Office, https://energyoffice.colorado.gov/climate-energy/ghg-pollution-reduction-roadmap (last visited Apr. 4, 2021). ↑

- Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-102(1)(a)(I) (2019); About the COGCC, Colo. Oil & Gas Conservation Comm’n, https://cogcc.state.co.us/about2.html#/about (last visited Oct. 26, 2021). ↑

- § 34-60-102(1)(a)(I). ↑

- SB 19-181: Protect Public Welfare Oil And Gas Operations, Colo. Gen. Assembly, https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb19-181 (last visited Oct. 17, 2021). ↑

- Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP, supra note 9. ↑

- Passage of Senate Bill 19-181: New Era of Change and Uncertainty for Oil and Gas Operations in Colorado, Kirkland & Ellis (Apr. 8, 2019), https://www.kirkland.com/publications/kirkland-alert/2019/04/new-era-of-change-and-uncertainty-for-oil-and-gas. ↑

- Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission Unanimously Adopts SB 19-181 New Mission Change Rules, Alternative Location Analysis and Cumulative Impacts, Colo. Dep’t of Nat. Res. (Nov. 23, 2020), https://dnr.colorado.gov/press-release/colorado-oil-gas-conservation-commission-unanimously-adopts-sb-19-181-new-mission. ↑

- See generally Ben Markus, All Systems Go For Colorado Oil And Gas, Despite Crackdown Efforts, CPR News (Oct. 2, 2019), https://www.cpr.org/2019/10/02/all-systems-go-for-colorado-oil-and-gas-despite-crackdown-efforts/. ↑

- Climate & Energy, Colo. Energy Office, https://energyoffice.colorado.gov/climate-energy (last visited Feb. 17, 2020). ↑

- H.B. 19-1261, 71st Leg., Reg. Sess. (Colo. 2019), https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb19-1261. ↑

- See Dale Ratliff, Senate Bill 19-181: Colorado Enacts First-of-Its-Kind Oil and Gas Legislation, 51 Am. Bar Ass’n Section of Env’t, Energy, & Res.: Trends 15, 16 (2019); Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP, supra note 9. ↑

- Press Release, COGCC, Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission Unanimously Adopts SB 19-181 New Mission Change Rules, Alternative Location Analysis and Cumulative Impacts (Nov. 23, 2020), https://cogcc.state.co.us/documents/media/Press_Release_Mission_Change_Vote_20201123.pdf. ↑

- Drew Kann, Oil and Gas Production is Contributing Even More to Global Warming than was Thought, Study Finds, CNN (Feb. 19, 2020), https://www.cnn.com/2020/02/19/world/methane-emissions-humans-fossil-fuels-underestimated-climate-change/index.html. ↑

- Oil and Gas, Env’t Integrity Project, https://environmentalintegrity.org/what-we-do/oil-and-gas/ (last visited Mar. 13, 2021). ↑

- Colo. Oil & Gas Conservation Comm’n v. Martinez, 433 P.3d 22, 25 (Colo. 2019). ↑

- Michael Elizabeth Sakas & Sam Brasch, Colorado Health Department Finds Proximity to Drilling Operations May Increase Health Risks, CPR News (Oct. 17, 2019), https://www.cpr.org/2019/10/17/colorado-health-department-finds-proximity-to-drilling-operations-may-increase-health-risks/. ↑

- See Grace Hood, Colorado is Poised to Clean Up the Air Around Oil and Gas Wells, CPR News (July 29, 2019), https://www.cpr.org/2019/07/29/colorado-poised-to-clean-up-air-around-oil-and-gas-sites/. ↑

- Colo. Rev. Stat. § 34-60-103(5.5) (2020). ↑

- § 34-60-105(1)(b)(I)–(IV). ↑

- SB 19-181: Protect Public Welfare Oil And Gas Operations, Colo. Gen. Assembly, https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb19-181 (last visited Oct. 17, 2021). ↑

- 2 Colo. Code Regs. § 404-1 app. B, 7 (2020). ↑

- Id. ↑

- §§ 404-1-301 to 404-1-314; §§ 404-1-901 to 404-1-915. ↑

- § 404-1-301(a). ↑

- Id. ↑

- § 404-1 app. B, 64. ↑

- § 404-1-303(a)(5)(B). ↑

- § 404-1-303(a)(5)(B)(i)–(vi). ↑

- § 404-1-314(a)(1). ↑

- § 404-1 app. B, 66. ↑

- §§ 404-1-314(a)(2)–(3). ↑

- § 404-1-314(c). ↑

- How Long Does an Oil Well Last?, Ranger Land & Minerals (May 22, 2020), https://www.rangerminerals.com/how-long-does-an-oil-well-last/. ↑

- § 404-1-304(b)(2)(B). ↑

- § 404-1 app. B, 79. ↑

- §§ 404-1-901 to 404-1-915. ↑