The Bears Ears National Monument (“Bears Ears”) in southern Utah is at the center of a live conflict in the conservation, public lands, and natural resource spaces. President Barack Obama established the 1.35 million acre monument in 2016 as an exercise of his protective authority under the Antiquities Act.[2] Conservation proponents supported the designation, but opponents criticized the action as a land grab by the federal government.[3] Less than a year later, President Donald Trump reduced the monument by eighty-five percent of its original size.[4] President Trump’s reduction sparked a debate about a president’s authority to revoke, replace, or diminish existing national monuments.[5] This issue is the focus of the lawsuit, Natural Resource Defense Council et al. v. Trump, brought by interested Native American Tribes and environmental organizations, which, as of this writing, is currently in front of the Federal District Court in D.C.[6]

For the people of the Hopi, Navajo, Ute, Ute Mountain Ute, and Zuni tribes (“the tribes”), the Bears Ears conflict has significance beyond the conservation and separation of powers issues presented in the ongoing lawsuit. Bears Ears was the first national monument proposed by tribes.[7] The original monument proclamation recognized the importance of tribal culture, experience, and knowledge and sought to protect the connection between Native people and the land.[8] To accomplish this, the Obama Proclamation established a collaborative management system between the managing federal agencies and an advisory council composed of representatives from each of the five tribes, called the Bears Ears Commission.[9] Advocates considered Bears Ears to be “a step toward repairing past injustices and reintegrating disenfranchised groups with the landscape.”[10]

By reducing Bears Ears, President Trump significantly reduced the role of the Bears Ears Commission as a tool of tribal comanagement—shared responsibility and authority between tribes and the federal government—of the monument.[11] After the reductions, the Bears Ears Commission only retained collaborative authority over ten percent of the original area.[12] The Trump Proclamation also added a seat to the Commission for the San Juan County Commissioner—a representative of the local government, rather than a representative of an interested tribe.[13] In contrast to the significant tribal involvement in establishing Bears Ears, a one-hour meeting constituted the entirety of tribal consultation in the reduction of Bears Ears and associated changes to tribal comanagement of the monument.[14]

In light of the ongoing court case and recent presidential election, the future of Bears Ears is uncertain. Any legal or political action will have significant consequences for the monument’s legacy of tribal participation in managing traditional lands belonging to the federal government. Tribal comanagement at Bears Ears could still take the original form described in the Obama Proclamation, the current form from President Trump’s reduction, or some unknown form arising out of the resolution of the current conflict. This uncertainty, while problematic in many ways, nonetheless presents an opportunity to explore alternative legal pathways for tribal comanagement of Bears Ears and other national monuments. Given both the historic and present connections between tribes and public lands, the value in exploring and developing legal justifications for tribal participation and collaborative management of public lands expands beyond the Bears Ears conflict at issue in this Article. The subdelegation doctrine involves partnerships between the federal agencies and outside entities—such as tribal governments—and presents one legal pathway for pursuing tribal comanagement. Thus far, it has received very scant treatment in literature on tribal comanagement.[15]

This Article explores the legal viability of tribes establishing comanagement agreements with public land agencies to manage national monuments under the subdelegation doctrine, using Bears Ears as a hypothetical test case. Part II describes the past, current, and proposed but rejected tribal comanagement structures for Bears Ears. Part III is a comprehensive analysis of the subdelegation doctrine and highlights what makes a comanagement system legal or illegal under the doctrine. Part IV combines the ideas of subdelegation and comanagement by applying the subdelegation doctrine to the Antiquities Act and a hypothetical tribal comanagement system for Bears Ears. This Article concludes by acknowledging that even though comanagement is a legally viable tool, the many political considerations involved in the tribes’ effort to preserve their interest in Bears Ears impacts the practicality and appropriateness of its use.

I. Tribal Comanagement and Bears Ears

The land and resources in the Bears Ears area are deeply tied culturally and historically to the Hopi, Navajo, Ute, Ute Mountain Ute, and Zuni tribes. Consequently, there is significant need to integrate tribal participation and knowledge into managing the Monument.

a. Cultural and Historical Connections Between the Tribes and Bears Ears

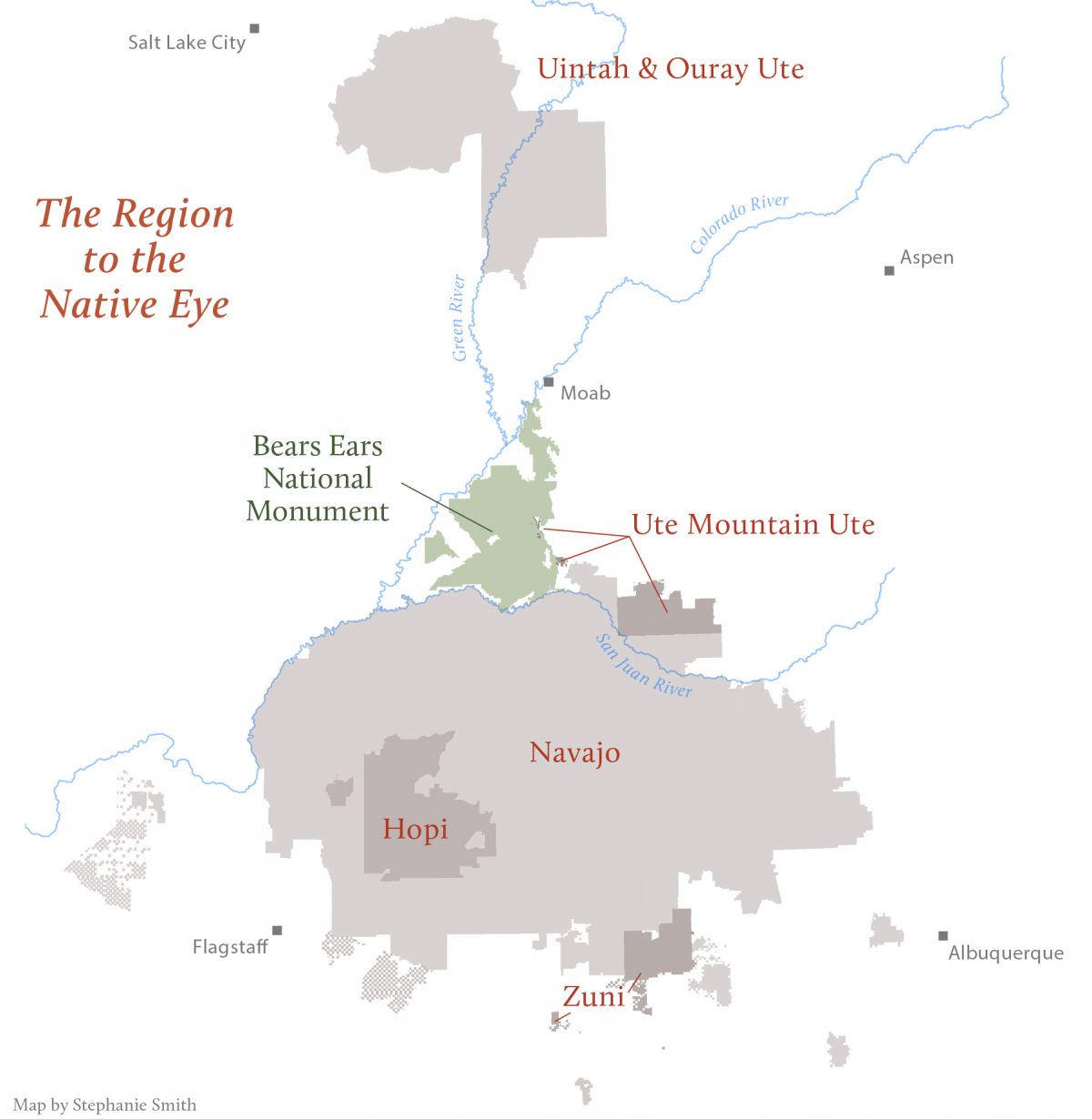

The Hopi, Navajo, Ute, Ute Mountain Ute, and Zuni tribes occupied Bears Ears since time immemorial.[16] Bears Ears contains the aboriginal lands, traditional trade routes, and ceremonial sites typical of the Colorado Plateau region.[17] Native people were forced out of Bears Ears through military efforts and pressure from non-Indian settlers throughout the 1860s–80s.[18] The federal government removed these tribes to various reservations across the West, and only a small portion of the Navajo Reservation and a community of Utes remain in the area around Bears Ears.[19]

Despite their removal, Native people from these tribes retain their connection to Bears Ears as a “place of origin stories.”[20] Tribal members travel to Bears Ears to hunt and collect piñon nuts, roots, berries, firewood, medicinal plants, and weaving materials in furtherance of their traditional cultural, religious, and subsistence practices.[21] Bears Ears contains more than 100,000 cultural and archaeological sites, many of which remain sacred to tribal communities who visit the sites for ceremonies and celebrations.[22] The National Trust for Historic Preservation considers Bears Ears to be “one of the most significant cultural landscapes in the  United States.”[23]

United States.”[23]

Figure 1: The Bears Ears Region in Relation to Tribal Lands[24]

Tribal elders and medicine people continue to tend to the Bears Ears landscape today.[25] The tribes’ beliefs and knowledge systems include practices of taking care of the land and resources at Bears Ears stemming from their historical relationship with the area.[26] Tribal participation is critical to the effort to care for Bears Ears.[27] It also allows tribes to reclaim their histories, protect traditional practices, and transform the area from a place of loss to one of cultural revival.[28]

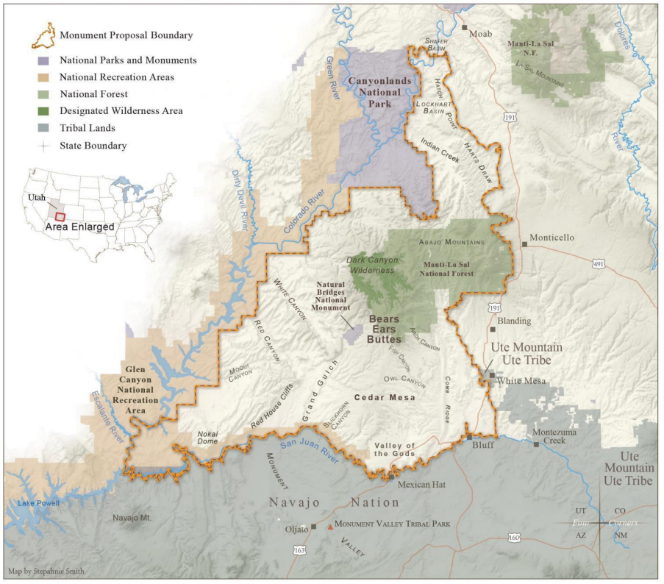

In this context of cultural and historical connection to the Bears Ears landscape, leaders from the Hopi Tribe, Navajo Nation, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Pueblo of Zuni, and Ute Indian Tribe formed the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition (“the Coalition”)—an intertribal organization composed of one board member from each tribe—with the goal of petitioning the Obama administration to establish the Bears Ears National Monument.[29] The group formed in 2015 following a research campaign conducted by a Navajo nonprofit, Utah Diné Bikéyah, which developed cultural maps, conducted interviews with tribal elders and members, and engaged academic experts to develop proposed boundaries for a 1.9 million acre national monument.[30] The Coalition set out to produce a comprehensive, compelling, and fundamentally tribal monument proposal.[31]

The Coalition kept tribal comanagement at the center of the Bears Ears proposal development.[32] Generally, tribal comanagement is the “sharing of resource management goals and responsibilities between tribes and federal agencies.”[33] Comanagement involves sovereigns engaging in shared and participatory management of land and resources.[34] The system allows for the inclusion of localized and historical tribal expertise on the species, habitats, and resources that a tribe relied on for centuries.[35] It also reduces disputes about interjurisdictional resources by institutionalizing a way for tribal governments to be proactive rather than reactive to actions taken by the federal government.[36] Public lands are often near current and historical tribal lands, and the federal government needs ways to integrate tribal rights, values, and culture into the comanagement scheme.[37] At its core, comanagement is a tool to facilitate understanding and communication.[38] Comanagement is considered the most authentic and participatory model of public participation.[39]

In practice, comanagement takes on many different forms. The amount of authority can range from complete government control with limited tribal input to primarily tribal control with limited government input.[40] Different types of comanagement include setting goals and management standards, implementing policy, and enforcing standards and regulations.[41]

A variety of tribal comanagement regimes are used for managing different aspects of fish and wildlife conservation, national forests, and national parks.[42] Agencies establish both formal and informal comanagement agreements through contracts, cooperative agreements, assistance agreements, and memorandums of understanding.[43] These agreements set policy goals, describe collaboration and issue resolution systems, and establish implementation duties.[44] Although informal agreements are not binding, they facilitate cooperation in the absence of a formal agreement.[45] Agencies are hesitant to formally give up their authority, and informal agreements allow tribes and the federal  government to still engage in comanagement.[46]

government to still engage in comanagement.[46]

Figure 2: Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition Proposed Boundaries for Bears Ears[47]

For the Bears Ears proposal, the Coalition held comanagement as a central theme and goal from the very first proposal meeting.[48] During the meeting, tribal members decided to pursue a true collaborative management relationship where the tribes would possess joint responsibility for managing the monument beyond consultation or serving as advisors.[49] The proposal described this desired substantive relationship as “collaborative management,” indicating the coequal status of the parties  to the proposed comanagement system.[50]

to the proposed comanagement system.[50]

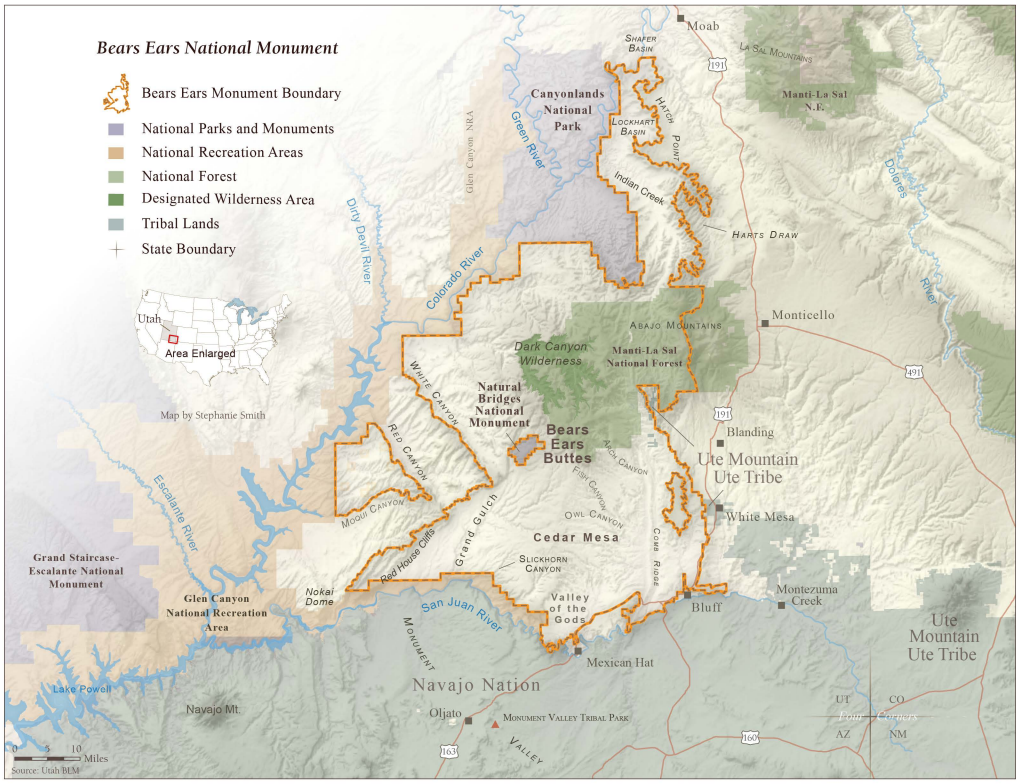

Figure 3: Bears Ears National Monument Boundaries Under the Obama Proclamation[51]

The tribes finalized the proposal over four subsequent meetings.[52] Significantly, each of the five tribes agreed on every word of the proposal.[53] On October 15, 2015, a delegation from the Coalition hand-delivered copies of the proposals to the Department of Interior (“DOI”) and the president.[54] The proposal marked the first time that the Antiquities Act was used at the behest and for the benefit of tribes.[55]

After submitting the proposal, the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition met with the Obama administration multiple times over the next year to reach an understanding about different aspects of the monument.[56] Then on December 28, 2016, President Obama established the Bears Ears National Monument pursuant to his authority under the Antiquities Act.[57] The Presidential Proclamation establishing the monument put the historical and cultural connection between Native people and the land at the center of the designation, stating “most notably the land is profoundly sacred to many Native American tribes . . . .”[58] The designation withdrew 1.35 million acres of land from development and identified the Bureau of Land Management (“BLM”) and the United States Forest Service (“USFS”) as the federal agencies in charge of managing the monument.[59]

The Obama Proclamation mandated that the agencies form an advisory committee composed of various stakeholders to “provide information and advice” regarding the development of a management plan for the monument.[60] Then it established a separate Bears Ears Commission (“Commission”) as an advisory panel consisting of one elected officer from each of the five tribes that formed the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition to “provide guidance and recommendations on the development and implementation of management plans and on management of the monument.”[61] The Obama Proclamation established the Commission to “ensure that management decisions affecting the monument reflect tribal expertise and traditional and historical knowledge.”[62]

The Obama Proclamation required the managing agencies to “meaningfully engage” the Bears Ears Commission in the development of the monument plan and subsequent management of the monument.[63] Additionally, the Obama Proclamation granted the Commission broad authority to “effectively partner” with the agencies.[64] Under the Obama Proclamation, agencies were also required to provide the Commission with a written explanation when rejecting any Commission recommendations.[65] These provisions made the Bears Ears Commission “the strongest example of federal and intertribal collaborative management in American law.”[66]

Language from the Coalition’s proposal on collaborative management was not included in the Obama Proclamation.[67] Instead, Obama established the Bears Ears Commission as a comanagement substitute which still received praise from the leaders of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition.[68] Although the Obama Proclamation did not provide for joint decision making, it did establish a “truly robust” role for tribal comanagement beyond traditional consultation.[69] The Hopi representative and cochair of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition Alfred Lomahquahu, stated that “we are confident that today’s announcement of collaborative management will protect a cultural landscape that we have known since time immemorial.”[70]

The five tribes named their representatives for the Bears Ears Commission on March 17, 2017.[71] However, the Bears Ears Commission only functioned for a short time before the Trump administration reworked the Commission during the reduction of Bears Ears.[72]

Although opening the area to development was the primary motivating factor for reducing Bears Ears,[73] the reduction process began on April 26, 2017 with an executive order directing the DOI to review national monuments larger than 100,000 acres in size for conformity with a list of Trump administration policy goals.[74] The Executive Order directed the DOI to consider “concerns of State, tribal, and local governments affected by a designation, including the economic development and fiscal conditions of affected States, tribes, and localities,” in addition to other policy considerations.[75]

In accordance with the Executive Order, Secretary Zinke prepared an interim report evaluating the Bears Ears National Monument.[76] In the report, Zinke commented on the Bears Ears Commission, noting that it “does not include the Native American San Juan County Commissioner elected by the majority-Native American voting district in that County.”[77] Navajo tribal member Rebecca Benally—an opponent to the monument—held the San Juan County Commissioner position at the time; however, she was not an elected tribal representative and consequently there was no reason to include her in the Bears Ears Commission.[78] Zinke then recommended that “the President [should] request congressional authority to enable tribal co-management of designated cultural areas within the revised BENM boundaries.”[79] After visiting Bears Ears and meeting with the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, along with other state and local stakeholders, Zinke stated that “[c]o-management will be absolutely key going forward and I recommend that the monument, and especially the areas of significant cultural interest, be co-managed by the Tribal nations.”[80]

In Zinke’s final report recommending the reduction of Bears Ears, Zinke echoed his suggestion to request congressional authority for tribal comanagement.[81] Zinke also suggested that the DOI should prioritize traditional use and tribal cultural rights along with other considerations in developing the management plan.[82] However, the final report lacked any discussion of the tribal participation in developing the Bears Ears proposal and the tribal comanagement system.[83] In recommending congressional authorization for tribal comanagement, Zinke pointedly ignored the existing comanagement system under the Bears Ears Commission and the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition’s original proposal of collaborative management systems.[84]

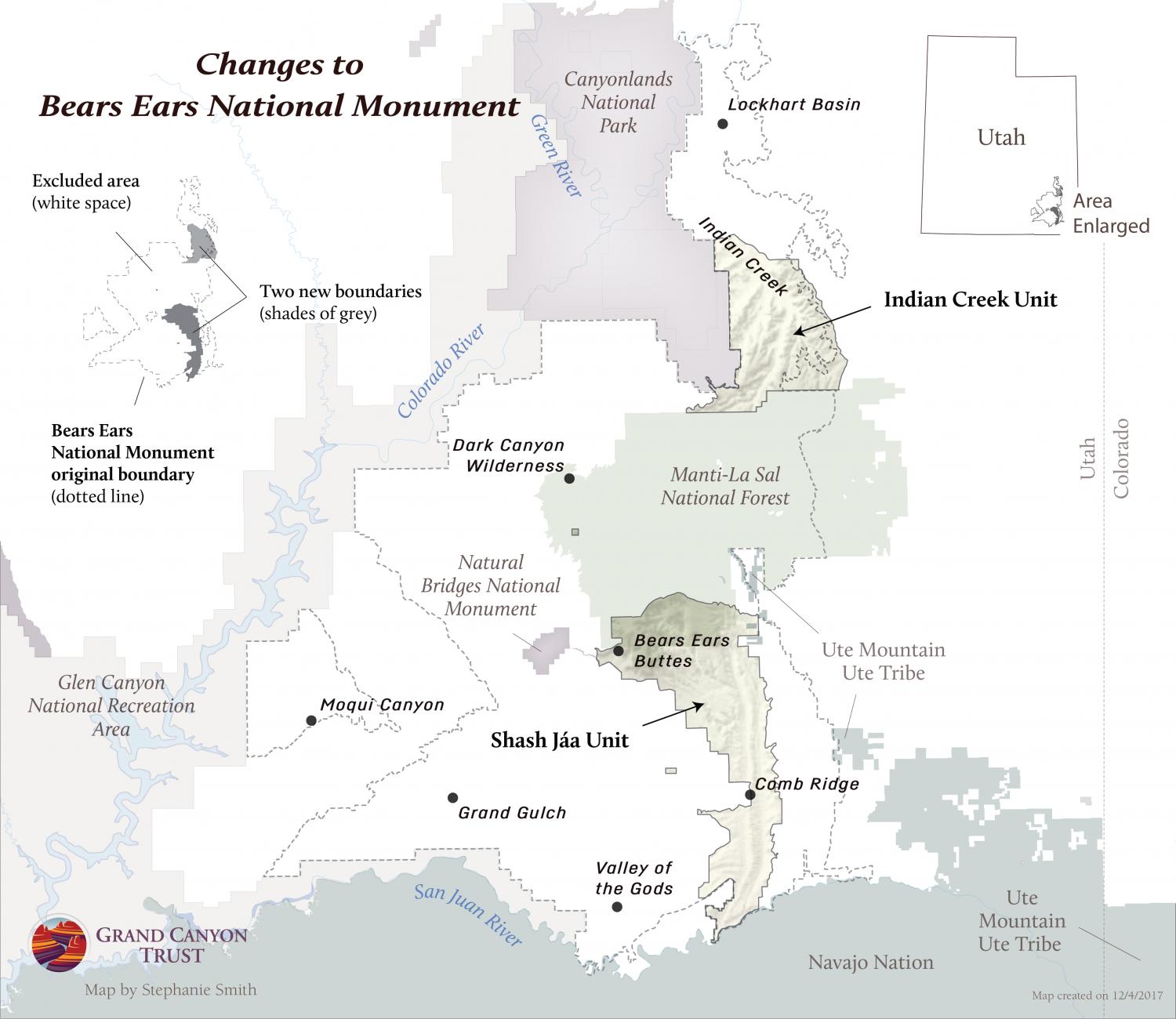

Based on these recommendations, President Trump replaced Bears Ears with two smaller monuments, the Shash Jáa and Indian Creek Monuments.[85] The Trump Proclamation revised the Bears Ears Commission by changing it to the Shash Jáa Commission, confining its authority to the Shash Jáa Monument, and taking the recommendations from the Zinke report by adding a seat for the San Juan County Commissioner.[86] The Trump Proclamation disingenuously claimed to make these changes “to ensure that the full range of tribal expertise and traditional knowledge is included in such guidance and recommendations.”[87] The Trump Proclamation reduced tribal control and protections for seventy-three percent of the documented archaeological sites in the monument.[88]

Tribal leaders were not consulted about the Shash Jáa Monument and claim that the use of the traditional name of the area is intentionally deceptive to imply tribal participation in and support for the reduction.[89] Clark Tenakhongva, the vice-chairman of the Hopi Tribe, criticized the process, saying it “shows the Trump administration’s disrespect of their trust responsibility to our tribal nations, their utter dismissal of our government-to-government relationship, and their serious disregard for our cultural patrimony.”[90]

Figure 4: Bears Ears National Monument Boundaries Under the Trump Reduction[91]

The comanagement system the tribes are left with through the Shash Jáa Commission is a far cry from the collaborative management imagined in the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition’s monument proposal. Worse, the Shash Jáa Commission was developed in the absence of significant or meaningful input of tribal voices. Considering the monument’s uncertainty, the tribes may have a chance in the future to replace the Shash Jáa Commission with a more significant form of tribal comanagement. This would present a second opportunity to advocate for collaborative management even beyond what was achieved in Obama’s Bears Ears Commission.

Comanagement agreements between the tribes and managing agencies present an additional legal pathway for tribes to pursue collaborative management of Bears Ears and other national monuments in the future. In order to evaluate the viability of this path, it is important to understand the legal doctrine that determines the legality of these types of agreements.

II. The Legal Ins and Outs of the Subdelegation Doctrine

Despite the Trump administration’s campaign to reduce Bears Ears National Monument, there will likely be some level of restoration of reduced lands and reinstitution of tribal participation in management for Bears Ears through either legal or political means. This Part examines the subdelegation doctrine to explore the legal parameters and limits of comanagement agreements between tribes and federal agencies for managing public lands.

Article I, Section I of the Constitution gives the legislative branch the exclusive authority to legislate.[92] Separation of powers principles limit the extent to which Congress can delegate its legislative power to an agency under the executive branch.[93] This limitation is known as the nondelegation doctrine.

Subdelegation is a subset of the nondelegation doctrine, where a federal agency delegates some portion of its authority—which Congress had delegated to that agency—to another party.[94] At its core, a subdelegation challenge is a constitutional claim alleging that an agency has improperly delegated some slice of legislative authority that is ultimately held by Congress.[95] Courts consider an unlawful subdelegation by an agency to be an abuse of discretion, not in accordance with the law, and in excess of an agency’s statutory jurisdiction.[96]

Subdelegation occurs when an agency further delegates authority to an outside entity.[97] Courts examine two interrelated issues to determine whether a subdelegation is lawful: (1) how an agency’s statutory obligations impact its subdelegation authority, and (2) whether an agency retains enough final review authority over a subdelegation for it to be lawful in the context of the agency’s statutory authority.[98] The two issues are intimately related, and courts often consider them together. An agency’s statutory obligations directly impact how much weight courts give to the final review authority question.

A court’s subdelegation analysis begins by reviewing the extent of existing statutory obligations.[99] Courts commonly state that “[t]he relevant inquiry in any subdelegation challenge is whether Congress intended to permit the delegatee to subdelegate the authority conferred by Congress.”[100] The general principle guiding courts’ consideration of statutory authority is that an agency may not subdelegate its authority to outside private or sovereign entities “absent affirmative evidence of authority to do so.”[101]

An agency’s statutory obligations are the first—and sometimes the most important—consideration in determining whether a subdelegation is lawful. Although there is no formal statement of how the two considerations relate, courts generally apply the subdelegation doctrine using the common principles asserted in the following sections. The guiding principle in the doctrine’s application is that the amount of emphasis a court gives to its final review authority analysis directly stems from its review of an agency’s statutory obligations.

- Agencies Possess Some Limited Subdelegation Authority Outside Clear Congressional Intent For or Against Subdelegation

Courts presume that a subdelegation is legal when there is affirmative evidence that Congress intended the agency to make that subdelegation.[102] Courts treat explicit statutory language allowing subdelegation by an agency as clear affirmative evidence of congressional authorization.[103] For example, where a statute allows an agency to perform its functions “directly, or by contract,” that agency has been clearly authorized to subdelegate that function.[104] When there is such clear congressional intent for subdelegation, courts easily find that a subdelegation is lawful with very little review of an agency’s retained final review authority.[105]

Courts also seem to defer to congressional intent when Congress clearly intends an agency to not have subdelegation authority. Most statutes are silent on whether an agency can subdelegate its authority. Although courts treat statutory silence inconsistently in their exploration of statutory obligations, in at least one case the court found statutory silence to preclude any subdelegation regardless of final review authority.[106] Here, again, the clear evidence of Congress’ grant of authority—or lack thereof—precluded a detailed examination of final review authority.[107]

However, most courts supplement statutory silence with the statute’s purpose and legislative history when looking for affirmative evidence of congressional intent. Courts generally hold that a statute does not have to expressly authorize a subdelegation for the delegation to be legal.[108] Instead, courts consider the statute holistically for affirmative evidence of congressional authorization to subdelegate agency authority.[109] Courts still require clear proof of legislative intent when looking beyond the text of a statute and hesitate to insert broad authority to subdelegate into statutes.[110]

Courts typically consider sole and express grants of responsibility to an agency to limit the agency’s authority to subdelegate that power. A foundation of the subdelegation doctrine is that “when Congress has specifically vested an agency with the authority to administer a statute, it may not shift that responsibility to a private actor.”[111] Most cases utilizing that doctrine interpret it to preclude an agency from shifting its entire responsibility and still allow limited subdelegation.[112] Courts seem to be careful to respect the limits on subdelegation authority set by Congress and are cautious in ensuring that a subdelegation is well within an agency’s limited power.

Where there are strong and express congressional grants of authority to an agency, “[r]elinquishment of any rights, authority or responsibility has to be done cautiously and in compliance with all of the public laws.”[113] Certain subdelegations may be considered categorically at odds with—and therefore limited by—Congress’ clear and specific delegation of a duty to an agency.[114] However, most courts find room for agencies to subdelegate some of their authority within those limits.[115] In these instances, courts’ consideration of final review authority serves to determine whether or not a subdelegation is permissibly within those limits.[116] If a subdelegation stays within those limits, it is legal.

Although all courts apply the same subdelegation doctrine, courts disagree about how to apply the doctrine to different types of outside entities. The broad category of “outside entities” includes private parties, state entities, tribal entities, and nonsubordinate federal agencies.[117] There is an apparent circuit split on whether the same standard applies to private parties and to sovereign entities, such as state or tribal authorities, which may possess independent authority over a subject matter. This disagreement stems from the Supreme Court case U.S. v. Mazurie, which explored whether Congress could validly delegate its constitutional authority over the sale of alcohol to a tribal council.[118] In that case, the Supreme Court stated that limits on Congress’ authority to delegate its legislative power are “less stringent in cases where the entity exercising the delegated authority itself possesses independent authority over the subject matter.”[119] Courts disagree on whether this delegation principle extends to subdelegations.

Two Ninth Circuit cases applied Mazurie’s less stringent standard to subdelegation cases.[120] In both cases, the Ninth Circuit considered the less stringent standard to apply to subdelegation of administrative authority to tribal, state, and local governments.[121] Conversely, the D.C. Circuit has stated that under the subdelegation doctrine, the same standard applies to private and state entities and clarified that the principles of Mazurie were limited to congressional delegations of legislative power, and did not apply to subdelegations of authority to outside entities.[122]

The D.C. Circuit criticized the Ninth Circuit for improperly relying on Mazurie without justifying the extension of the principle beyond congressional delegation.[123] As an additional justification for going against the Ninth Circuit cases, the D.C. Circuit stated that the principle was not necessary for the decision in either case.[124] The Ninth Circuit has yet to comment on the D.C. Circuit’s criticism, and no other circuit has addressed the issue of whether the same standard applies to sovereign and private entities.

It is unclear whether courts outside the Ninth and D.C. Circuits will apply the less stringent standard to sovereign entities. Regardless of which standard a court would apply to a case, the general analysis under the subdelegation doctrine remains the same. Even though the Ninth Circuit cases used Mazurie’s less stringent standard, the court still applied the subdelegation doctrine and based its decision on statutory obligations and final review authority. Although the level of stringency may slightly impact a court’s subdelegation analysis, the core analysis remains the same.

When an agency subdelegates its authority to an outside entity, that agency must retain final review authority over the entity’s actions.[125] When an agency does not retain final review authority, a subdelegation is unlawful.[126] Although a court’s stringency when analyzing final review authority can vary depending on an agency’s statutory obligations related to subdelegation, there are universal trends that inform a court’s decision.

Final review authority generally requires some active exercise of agency power over a delegated decision. Where the structure of a subdelegation agreement procedurally ensures that an agency “must engage in meaningful review” of every substantive decision made or action taken by an outside entity, that agency clearly retains final review authority.[127] An agency can also retain final review authority by preserving its ability to oversee challenges to determinations made by an outside entity.[128] Additionally, an agency can subdelegate a single decision that is a part of a larger decision-making process of which the agency is still in charge of.[129] In every one of these situations, the agency retains some independent and meaningful control over an outside entity’s exercise of its subdelegated authority.

In contrast, generalized agency oversight without any direct authority does not constitute final review authority. Courts are clear that an agency’s ability to approve a delegated decision without any substantive review—or a “rubber stamp” approval—does not constitute final review authority.[130] Subdelegation regimes that intentionally minimize agency control through mechanisms such as relying on nonagency funding, limiting voting rights for agency representatives, or completely excluding the agency from participating in decision-making procedures and politics, clearly undermine an agency’s final review authority.[131] An agency’s retained power to terminate a cooperative agreement with an outside entity is not significant enough in itself to constitute final review authority.[132] Similarly, the authority to take back subdelegated authority if an outside entity fails to or chooses not to exercise it is not enough to establish final review authority.[133] An agency must have some meaningful structural and procedural control over an outside entity’s exercise of its subdelegated authority.

Additionally, an agency must engage substantively in all decision making. Final review authority requires more than just an agency’s ability to reject a decision, it must also participate in approving decisions.[134] Considering agency silence as approval of outside-entity decisions is impermissible.[135] For the same reason, an outside entity’s ability to unilaterally reject a decision also defeats final review authority.[136] In cases where the outside entity exercises its rejection power, it “supplant[s] [the agency] as a final decision-maker.”[137] In order for a subdelegation to be legal, an agency must retain final review authority over all decisions and actions made under the delegated power.

The legality of comanagement agreements under the subdelegation doctrine is incredibly involved and complex. The two-consideration system for judicial review under the doctrine is deceptive in its seeming simplicity. The doctrine’s nuance is often overlooked by academics, agencies, and outside entities when discussing, reviewing, and forming comanagement agreements.[138] A deeper understanding of the subdelegation doctrine is critical to creating long-lasting and meaningful comanagement structures that will be upheld by courts.

III. The Legal Viability of a Comanagement Agreement Between the Tribes and Managing Agencies for Bears Ears Under the Subdelegation Doctrine

Determining whether a comanagement agreement between the tribes and federal managing agencies is a legally viable tool for tribal comanagement at Bears Ears requires applying the subdelegation doctrine to a hypothetical Bears Ears comanagement agreement. This consideration begins with an in-depth exploration of the managing agencies’ obligations under the Antiquities Act and other interrelated public land management statutes. The exploration of congressional intent spans BLM and USFS management statutes, foundational American Indian law principles, and specific American Indian statutes related to public land management. The analysis is general and broadly applicable to tribal comanagement of any national monument, BLM land, or national forest.

This consideration then turns to a broad exploration of the types of comanagement authority a hypothetical intertribal organization could exercise in light of the public lands and American Indian law statutory landscapes. Since this step of the process is fact-specific, the analysis provides general limits and considerations to consider and applies them generally in the context of Bears Ears.

a. Consideration One: The BLM and USFS’s Subdelegation Authority Under the Antiquities Act, Public Land Statutes, and American Indian Law Principles and Statutes

Under the subdelegation doctrine, analysis begins with determining “whether Congress intended to permit the delegatee to subdelegate the authority conferred by Congress.”[139] The legal viability of a comanagement agreement between the tribes and managing agencies depends on finding “affirmative evidence of authority to [subdelegate management authority]”[140] while reviewing the BLM and USFS’s statutory obligations for managing national monuments. This threshold question determines whether any comanagement system between the tribes and managing agencies at Bears Ears would be legal. Although there is a lot of uncertainty in how the subdelegation doctrine would be applied to the complex statutory scheme for national monument management, this Article argues that Congress intended land management agencies to have authority to subdelegate public land management to tribal and intertribal organizations.

i. The Antiquities Act is Silent About Subdelegation Authority

The Antiquities Act (16 U.S.C. §§ 431–433) grants the President the authority to establish national monuments to protect “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest.”[141] Although the Act gives the President designation authority, it delegates management authority to the land management agencies that already have jurisdiction over the reserved lands. Sections 3 and 4 of the Act give the Secretaries of the Interior, Agriculture, and Army permitting and regulatory authority over national monuments.[142] Section 2 authorizes the Secretary of Interior to accept the relinquishment of lands containing objects on unperfected claims and private lands.[143] In practice, relevant land management agencies are involved in the preparation of establishing proclamations and subsequent management plans for national monuments.[144]

The statute itself lacks explicit language allowing subdelegation.[145] The Antiquities Act’s silence on the issue immediately distinguishes this case from the easy analysis when there is clear textual authorization to subdelegate.[146] However, the analysis does not stop there. Except in rare cases, courts look beyond the text of the statute when looking for affirmative evidence of subdelegation authority and congressional intent.[147]

The first extra-textual place to examine is the purpose and legislative history of the Antiquities Act. Congress originally enacted the Act in 1916 based on concerns about protecting Native American sites in the Southwest from looting and desecration.[148] Congress passed the Act at a time when conservation law excluded and was often detrimental to Native American people, and the drive for preservation of antiquities came primarily from archeologists.[149] However, as time passed, the underlying purpose of the Act shifted to include and respect Native American people. In the last decade, the proclamation and management plan processes have changed to better include Native voices as modern national monuments address tribal rights to access and use the lands.[150] Congress has implicitly sanctioned this shift in the underlying policies of the Antiquities Act by silently allowing the continued practice.

Overall, the Antiquities Act does not provide much evidence for or against subdelegation authority for national monument management. The statute is silent on the issue and the purpose of the statute is uncertain in the light of a fundamentally changed policy landscape and implementation of the statute. However, evidence of Congress’ intent regarding national monument management is not limited to the Antiquities Act. The Antiquities Act is unspecific about agency management authority generally, not just the agencies’ subdelegation authority. The land use planning process for national monuments is subject to other land management statutes that more clearly establish the authority of the BLM and USFS.[151] National monuments are also subject to a slew of federal American Indian law statutes affecting the BLM and USFS’s land management authority.[152] These statutes reflect and integrate Congress’ policy shift on Native American participation in land management.

A complete review of Congress’ intentions regarding land management agencies’ authority and ability to subdelegate that authority must consider the multiple statutes controlling national monument management, not just the Antiquities Act. In High Country Citizens’ Alliance v. Norton, the court reviewed the National Park Service Organic Act, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park and Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area Act, and the Wilderness Act in its exploration of congressional intent.[153] While considering Bears Ears, a reviewer must similarly look at the full range of statutes establishing agencies’ authority over national monument management.

ii. Associated Land Management Statutes Allow Some Limited Subdelegation of Authority

Management responsibility for Bears Ears is split between the USFS for national forest land and the BLM for all other monument land.[154] Consequently, Bears Ears is managed according to each agency’s respective management standards.[155] Cultural and historical resource management and planning are included throughout the various land management statutes at play in the management of Bears Ears.[156] These statutes are a key source of evidence for Congress’ intent to allow managing agencies to subdelegate their management authority to tribes.

The BLM manages its lands, including national monument lands, under the Federal Land and Policy Management Act (“FLPMA”) (43 U.S.C. § 1701 et seq.).[157] Additionally, the BLM manages Bears Ears as a part of the National Landscape Conservation System.[158] Generally, FLPMA directs DOI agencies to manage lands for the protection of historical and archeological values as one of many competing land policies.[159] FLPMA also specifically directs DOI agencies to manage lands with public involvement from tribes as well as other listed entities.[160]

The land use planning section of FLPMA states, “[t]he Secretary shall, with public involvement and consistent with the terms and conditions of this Act, develop, maintain, and, when appropriate, revise land use plans which provide by tracts or areas for the use of the public lands.”[161] The section then explicitly brings in tribes, providing that when developing these plans “the Secretary shall . . . coordinate the land use inventory, planning, and management activities of or for such lands with the land use planning and management programs of . . . or for Indian tribes by, among other things, considering the policies of approved State and tribal land resource management programs.”[162] The statute additionally states, “[i]n implementing this directive, the Secretary shall, to the extent he finds practical, keep apprised of State, local, and tribal land use plans [and] assure that consideration is given to those State, local, and tribal plans that are germane in the development of land use plans for public lands . . . .”[163] Under FLPMA, DOI agencies have general authority to enter cooperative agreements for “the management, protection, development, and sale of public lands.”[164]

The USFS manages its lands under a different set of statues: the National Forest Management Act (“NFMA”) (16 U.S.C. § 1600 et seq.) and the Multiple-Use Sustained Yield Act (“MUSYA”) (16 U.S.C. § 583 et seq.).[165] NFMA does not specifically address tribal participation in land management.[166] However, NFMA does require the USFS to use a “systematic interdisciplinary approach to achieve integrated consideration of physics, biological, economic, and other services.”[167] Under this provision, NFMA’s implementing regulations call for the identification, consideration, and management of “significant cultural resources.”[168] MUSYA allows the USFS to enter into cooperative agreements with “public or private agencies, organizations, institutions, or persons” for various management purposes, such as considering cultural resources.[169]

Both land management statutory schemes offer affirmative evidence of Congress’ intent to allow subdelegation of land management authority to outside entities. In the case of the BLM, Congress explicitly mandated that DOI agencies develop land management plans with public participation and requires the agencies to coordinate with tribal management programs. Although Congress does not specifically state that DOI agencies can subdelegate management plans to tribal entities, the different provisions of the statute demonstrate a general awareness of and willingness to integrate tribal voices into the management process. This awareness puts the BLM’s management authority squarely within the category of cases where Congress’ express grant of authority to a department Secretary allows for some subdelegation as long as the Secretary does not “completely abdicate” its statutory responsibility. The broad acknowledgement of tribal interests in FLPMA broadens the amount of authority the BLM can subdelegate to tribes before running afoul of these limits.

In contrast, NFMA and MUSYA make express and sole delegations of authority to the Secretary of Agriculture and USFS without explicitly integrating tribal interests. The statutes’ silence on subdelegation still brings the USFS’s subdelegation authority into the same realm as the BLM’s, where some subdelegation is permissible. However, the limits on that subdelegation authority might be perceived to be higher, impacting a court’s consideration of what constitutes USFS final review authority.[170]

Both statutes provide at least some affirmative evidence that Congress intended the BLM and USFS to include various types of outside entities when managing land to some extent. Although the statutes’ silence on subdelegation provides limits to the agencies’ subdelegation authority, when considering tribal comanagement, those limits must be considered in light of relevant American Indian law principles and statutes impacting agencies’ land management duties.

iii. American Indian Law Principles and Statutes Expand the BLM and USFS’s Limited Subdelegation Authority

Contemporary federal public land management and American Indian policy “have always been intertwined.”[171] Consequently, tribal comanagement can only be understood in the context of fundamental principles of American Indian law and the resulting legal and political framework for public land management.[172] The complex statutory framework arising from these fundamental principles is a strong source of evidence of congressional intent to allow some subdelegation of public land management authority to tribes. Each statute is a recognition and protection of tribal decision-making authority as sovereign governmental authorities, rather than as ordinary stakeholders.[173] This additional layer of American Indian law expands the amount of limited subdelegation authority the BLM and USFS have when dealing with tribes for areas like Bears Ears.

1. American Indian Law Principles

Informal and formal tribal participation and comanagement of public lands are based on a few fundamental principles of American Indian law: tribal sovereignty and self-government, the trust responsibility between tribes and the federal government, and tribal reserved treaty rights.[174] These principles are the base of congressional policy that has supported a general shift toward tribal comanagement of different resources and lands, and generally evidences that Congress envisions a place for tribes in public land management in passing its land management and American Indian statutes.

Congressional policy and law recognizes some degree of tribal sovereignty.[175] Tribes as sovereigns have the prerogative to care for their people, culture, and economic well-being.[176] Scholars generally understand tribal comanagement agreements to be exercises of that sovereignty.[177] Comanagement can be the exercise of two sovereigns working together in a mutual and participatory way to manage resources and land in which both possess a shared interest.[178] This practice is a recognition of tribes’ shared power over public land decision making as a sovereign government rather than a commentator.[179] Federal agencies have reconsidered their relationship with tribes by engaging in various comanagement regimes at a government-to-government level, recognizing the congressional shift to self-determination policies.[180] Congress has gone as far as to recognize, protect, and occasionally encourage tribal authority over off-reservation resources and land.[181] Tribal sovereignty inherently includes authority over cultural resource protection and land and resource management.[182] Congress has recognized this notion in its policies and its authorization of authority to public land management agencies.

The trust obligation owed by the federal government to Native American tribes also necessitates substantive tribal engagement in federal land management decisions.[183] Under the trust obligation, the United States has an obligation to protect and preserve tribal sovereignty and procedurally incorporate tribes into decision making.[184] Congress has codified this obligation through multiple statutes, discussed infra, necessitating tribal consultation in land management planning.[185] The United States must both protect tribal resources and preserve and strengthen tribal ability to exercise sovereign control over those resources through systems like comanagement.[186] Congress’ trust obligation to tribes contextualizes its authorization of authority to land management agencies.

Reserved treaty rights have also strengthened the frequency and legitimacy of certain tribal comanagement agreements, particularly in the fish and wildlife context.[187] Some treaties give tribes protected rights to reserved resources, and the federal government is obligated to uphold those treaty rights as a part of the trust obligation.[188] These reserved treaty rights typically include some combination of the rights to hunt, fish, trap, and gather on and off of reservations.[189] Courts have found that tribes have a legitimate and enforceable expectation that the federal government will not degrade their reserved rights to resources and associated habitats.[190] Rights to resource and habitat protection include inherent rights to meaningful tribal participation in decision making regarding those resources and habitats.[191] Where they occur, reserved treaty rights would presumably be strong evidence for congressional intent to allow tribal participation in land management.

However, reserved treaty rights are a fact-specific consideration rather than a general American Indian law principle immediately applicable to all tribes. In the context of Bears Ears, reserved treaty rights serve a small role. Hunting and collecting piñon nuts, roots, berries, firewood, medicinal plants, and weaving materials is an important aspect of tribal use on Bears Ears, but this use is not based entirely on reserved treaty rights.[192] The Hopi and Zuni reservations were not established by treaties and the tribes do not have reserved treaty rights.[193] The Navajo, Ute, and Ute Mountain Ute tribes have reserved off-reservation hunting rights, but not explicit gathering rights.[194] The treaty rights that do exist for the tribes involved with Bears Ears are additional evidence of congressional intent to include these tribes specifically in habitat management decisions. Congress’ recognition of reserved treaty rights in general and integration of tribal participation in various land management statutes also supports tribal participation in managing public lands.

2. American Indian Law Statutes

Tribal sovereignty, the trust obligation between the United States and tribes, and implied treaty rights all support the need to integrate tribes into decision making for public lands.[195] Congress has explicitly recognized this need and obligated land management agencies to engage tribes through various statutes discussed subsequently.[196] These statutes require federal agencies to consult with tribes and consider tribal concerns before undertaking public land projects with effects on Native American cultural and religious resources.[197] Both individually and collectively, these statutes provide affirmative evidence of Congress’ intent to allow the BLM and USFS to relinquish some of their management authority to tribes.

The “most important” of these consultation statutes is the National Historic Preservation Act (“NHPA”) (54 U.S.C. § 100101 et seq.), which is a procedural statue intended to preserve historical and cultural resources and also enhance and encourage tribal interest in historic preservation.[198] The Act is considered the “cornerstone of federal historic and cultural preservation policy.”[199] Section 106 of the NHPA requires agencies to consult with specific groups when taking actions affecting historic and traditional cultural properties.[200] The Act specifically directs agencies to consult with tribes “likely to have knowledge of or concerns” about impacted historic properties.[201] Under this section, federal agencies regularly address matters of tribal concern for actions on public lands.[202] Due to the relationship between federal public land and traditional American Indian land, tribal consultation is the most common use of Section 106 consultation.[203]

Actual tribal participation under the NHPA consists of tribal consultation on cultural resources and participation in informal management agreement negotiations.[204] During consultation, tribes assist in identifying areas of cultural importance on public lands and preparing cultural resources surveys.[205] If a proposed action is likely to impact traditional cultural properties, tribes can participate in mitigation discussions and negotiations along with other private and governmental interested parties.[206] The consultation framework established by the NHPA demonstrates Congress’ intent to actively include and engage tribes as sovereigns in public land decisions impacting cultural resources.[207]

Other statutes similarly require tribal consultation and participation in decision making for cultural resources.[208] The Archaeological Resources Protection Act (“ARPA”) (16 U.S.C. §§ 470aa–470mm) requires notice and consultation when agencies issue permits for excavation of cultural and religious resources on federal lands.[209] Federal agencies have interpreted these statutory mandates to require significant tribal engagement. ARPA’s implementing regulations require substantial tribal participation in granting permits, allow tribes to impose conditions on these permits, require tribal notification when applications for excavation or disturbance are submitted, and authorize managing agencies to meet with tribes to develop avoidance and mitigation measures.[210] ARPA is an important part of the coordinated consultation process that Congress created to bring tribes into public land decisions.

Consultation is also an important informal element of the Native American Graves Protection and Reparation Act (“NAGPRA”) (25 U.S.C. § 3001 et seq.).[211] NAGPRA seeks to protect Native American graves and related cultural artifacts by giving tribes ownership and control over excavated or discovered tribal human remains and cultural items found on federal lands.[212] These substantive protections of cultural resources entitle tribes to notice and consultation when cultural items are inadvertently discovered and require tribal approval for excavation and removal.[213] NAGPRA brings specific cultural items—human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony—into the consultation process under NHPA and other statutes in a substantive way, increasing statutory tribal authority over public land resources.[214]

The American Indian Religious Freedom Act (“AIRFA”) (42 U.S.C. § 1996 et seq.) also contributes to the coordinated tribal consultation requirements applicable to public land management.[215] AIRFA requires agencies to consider effects of public lands development on Native American religion.[216] The Act makes it the policy of the United States to protect and preserve inherent rights of Native American people to exercise their religion “including but not limited to access to sites, use and possession of sacred objects, and the freedom to worship through ceremonial and traditional rites.”[217] AIRFA does not create substantive, enforceable rights, but the considerations may be required to be included in the coordinated consultation process involving other land management statutes.[218] AIRFA is yet another example of Congress’ intention for tribes to be involved in public land management.

For the DOI, Congress’ intent to give management authority over federal lands to tribes goes beyond consultation. The Tribal Self-Governance Act (“TSGA”) (25 U.S.C. §§ 458aa–hh) authorizes DOI agencies to transfer management authority over federal public lands with “special geographical, historical, or cultural significance” to tribes, to those tribes.[219] The Act establishes a government-to-government negotiation process and obligates agencies to negotiate with tribes.[220] It also allows tribes to exercise authority over public land management through Annual Funding Agreements, which provide tribes with federal funds to implement federal programs.[221] However, this authority is somewhat limited in that it only applies to tribes that meet a narrow set of requirements to petition for program management.[222] Regardless, TSGA is significant for tribal participation and control over federal land management.[223]

TSGA reflects Congress’ recognition of implicit tribal sovereignty by expanding self-determination policy over public lands.[224] It also explicitly provides affirmative evidence that Congress intends DOI agencies to be able to subdelegate land management authority over DOI lands. TSGA is a significant affirmative step toward tribal comanagement and integrating tribal cultural values, traditional knowledge, and traditional management practices into public land management.[225]

iv. Comprehensive Statutory Analysis Considering the Antiquities Act, FLPMA, NFMA, and American Indian Law Together

Bringing in American Indian law principles and statutes pertaining to tribal consultation and cultural resource management changes the subdelegation analysis under the Antiquities Act, FLPMA, and NFMA. Under public land statutes, the BLM and USFS have some subdelegation authority over public lands—including national monuments—but that authority is limited. However, when the outside entity is a tribal or intertribal organization, statutes pertaining to tribal consultation and cultural resource management roll back those limitations to a certain extent. Each of the consultation and cultural resource provisions discussed supra provide affirmative evidence that Congress intended tribes to be procedurally involved in public land management. For many of the statutes, that involvement is already exercised in a substantive way.

This body of law would have significant impacts in considering whether the USFS or BLM retain final review authority in a comanagement agreement with an intertribal entity for Bears Ears. The legitimacy of the less stringent standard for sovereign entities explored supra Part III.a.ii. is still uncertain. However, for sovereign tribal entities, the vast statutory scheme Congress created to integrate tribal interest and participation into public land management likely creates this less stringent standard in function, if not in name. Congress expressly gave tribes a role in public land management and tribal exercise of authority over public lands within those statutory bounds would be an unquestionably legitimate starting place for a comanagement agreement. Expansion beyond those bounds seems possible as an exercise of the principles of sovereignty, the trust obligation, and reserved treaty rights, on which Congress based these statutes. These principles are all sources of tribes’ independent authority over public land management of the kind the court looked for in Mazurie to justify a less stringent standard of review for delegations of authority. Federal agencies already implement broad, substantive requirements based on statutory procedural requirements and these principles.

The BLM possesses even more authority to subdelegate management authority over Bears Ears to tribes. For the DOI, which excludes the USFS, TSGA provides a clear congressional authorization to shift management authority to tribes. A court could consider this authorization to be clear textual evidence of the kind that would preclude significant final review authority analysis.[226] If that is the case, a comanagement agreement between the BLM and an intertribal entity for the management of Bears Ears would be legal, outside a complete abdication of final review authority by the BLM. Even if the authorization in TSGA is not considered to be quite to that level, it would still be considered strong affirmative evidence of Congress’ intent to allow tribes to lawfully exercise a significant amount of management authority over public lands.

The consideration of the USFS and BLM’s statutory authorities and abilities to subdelegate sets up the question of final review authority. The Antiquities Act is silent on subdelegation authority, but the USFS and BLM’s land management statutes seem to allow room for some limited subdelegation of land management authority to outside entities. The amount of subdelegation authority should be presumed larger when subdelegating to tribal entities based on Congress’ comprehensive statutory scheme integrating tribal participation into public land management.

b. Consideration Two: the BLM and USFS’s Final Review Authority under a Hypothetical Comanagement Agreement with the Tribes

The first consideration of the USFS and BLM’s subdelegation authority under the Antiquities Act, public land statutes, and American Indian statutes sets the framework for how a court would consider an agency’s final review authority over a comanagement agreement. Under these statutes, the USFS and BLM likely have some subdelegation authority, but it is limited. Consideration of final review authority will largely be an analysis of whether an agreement stays within those limits.

This fact-specific analysis follows a few general principles discussed above. To retain final review authority, an agency must engage in meaningful review of an outside entity’s exercise of subdelegated authority.[227] When agencies have more latitude to subdelegate, there is a lower threshold for what constitutes as adequate final review authority.[228] However, in all cases, a “rubber stamp” approval—where agencies do not engage in substantive review of outside entity decisions—does not constitute final review authority and will be considered illegal.[229] Additionally, agencies must have substantive authority beyond reserved decision-making authority over only one or two issues.[230]

Applying these principles to hypothetical agreements between the USFS and BLM and an intertribal organization composed of the tribes reveals a range of the types of authority tribes could legally possess under the subdelegation doctrine.

Starting at one extreme, an agreement that gives advisory authority to the tribes similar to the authority of the Bears Ears Commission would fall squarely within the USFS and BLM’s subdelegation authority. The advisory role and “meaningful engagement” imagined for the Bears Ears Commission encompasses the same types of authorities Congress explicitly gave tribes through the various consultation and cultural resources statutes discussed above. With the tribes serving in an advisory role, the agencies never actually give up decision-making authority. Decision making would ultimately remain in the agencies’ hands and every recommendation or decision made by tribal entities would be substantively and independently reviewed by the agency. The structure of the advisory framework ensures that the agency retains final review authority.[231]

The tribes could theoretically use comanagement agreements to reestablish this advisory authority over the 1.1 million acres of BLM and USFS lands removed from Bears Ears by the Trump administration. Opponents would have a difficult time challenging that type of advisory authority in court under the subdelegation doctrine.

Regarding the other extreme, a complete shift of all management and enforcement responsibility over Bears Ears to tribes would be outside the legal bounds of a subdelegation. The BLM might have broad authority to subdelegate significant amounts of substantive authority to tribes under TSGA. Yet, the BLM would still need to substantively review and hear appeals about tribal decisions.[232] The scope and types of subdelegated authority are likely more limited for the USFS, but those bounds are less clear. In either case, agencies must remain active participants with substantive review over the management of Bears Ears. The subdelegation doctrine does not allow tribes to entirely replace federal agencies in public land management.

Short of that extreme, the subdelegation doctrine allows the BLM and USFS to shift quite a bit of policy, management, and enforcement authority to tribes considering the statutory analysis supporting a less stringent standard for tribal comanagement. A true collaborative management approach, as originally imagined and proposed by the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, would likely be legal under the subdelegation doctrine for Bears Ears. Under collaborative management, the tribes seem to imagine a system where tribes and federal agencies manage Bears Ears as partners with shared authority. This system would ensure that agencies substantively participate in and review management decisions. As collaborators, the tribes could ensure a voice and hand in managing Bears Ears and assume more substantive control over management beyond the normal consultation requirements. However, the tribes would not become the primary managers of Bears Ears and the BLM and USFS would not inappropriately usurp Congress’ original delegation of management authority to them. A court’s specific application of the subdelegation doctrine is uncertain, but it is reasonable to believe that a court would uphold collaborative management of Bears Ears established through an informal agreement between the agencies and the tribes.

Beyond decision-making authority, the tribes can also take over some management functions for Bears Ears based on the tribes’ means and interest. Existing tribal comanagement agreements for national monuments provide an idea of the types of functions the tribes could engage with. The BLM and Cochiti Pueblo signed cooperative agreements for the management of the Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument in north-central New Mexico.[233] Under the agreements, the Pueblo have significant management responsibilities for trail maintenance, visitor services work, law enforcement coordination with the BLM, and full time staff recruitment to manage and monitor the monument with BLM funds.[234] The Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains National Monument in southern California is also subject to comanagement agreements between the BLM and the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians.[235] These agreements generally establish a commitment to work together, set up an assistance program to remove tamarisk from watersheds shared with the tribe, and place tribal cultural resources at the forefront of the managing committee’s thoughts.[236] Although the application of any of these functions in a cooperative agreement between the BLM or USFS and the tribes for Bears Ears would require a fact-specific analysis, this type of shared system of management functions would likely be legal under the various public lands and American Indian statutes applicable to national monument management.

The tribes could recapture significant decision-making authority and power over management functions for Bears Ears by using informal cooperative agreements with the BLM, USFS, or both. The tribes have broad latitude under the controlling statutory structures to work with federal agencies in a substantive way, while still preserving agency final review authority in a way that does not offend separation of powers notions. These types of agreements are likely a legally viable pathway for the tribes to pursue true collaborative management for Bears Ears and other BLM and USFS lands.

The opportunity to comanage Bears Ears is an important issue for the tribes who retain a spiritual and cultural connection to the land and for the general recognition and empowerment of tribal sovereignty. The Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition proposed a visionary collaborative management regime for the monument that resulted in a strong comanagement substitute, recognizing and incorporating the tribes into Bears Ears management as an advisory council. That achievement was undermined when the Trump administration reduced Bears Ears, limited the Bears Ears Commission’s jurisdiction, and restructured the Commission to include voices that were not representative of tribal interests.

In the face of an uncertain future for Bears Ears, cooperative agreements between the tribes and the managing agencies for the monument provide a legally viable pathway for the tribes to pursue: (1) truly collaborative management of the monument beyond the authority of the Bears Ears Commission, and (2) management and advisory authority over the BLM lands removed from the monument designation.

The choice to pursue either option involves complex political considerations about the viability, volatility, and enforceability of using different legal structures for comanagement. Regardless of which structure is used, the most important consideration is that tribes be actively involved in developing any comanagement system. Comanagement agreements under the subdelegation doctrine are one additional, legally viable option for the tribes of the Bears Ears Commission to consider in their continued effort to retain, protect, and strengthen the core tribal elements of Bears Ears.

- * Daniel Franz is a new lawyer in the environmental, natural resources, and administrative legal spaces currently working on federal energy law issues as a fellow. Thank you to Professor Krakoff for inspiring my interest in the topic of this Article and supporting its development. Another thank you to the wonderful staff of the Colorado Natural Resources, Energy & Environmental Law Review for their work. ↑

- Sarah Krakoff, Public Lands and the Public Good: The Limitations of Zero-Sum Frames, in Environmental Law Institute, Beyond Zero-Sum Environmentalism 133, 134–35 (Sarah Krakoff, Melissa Powers, & Jonathan Rosenbloom eds., 2019) [hereinafter Krakoff I]. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Bill Doelle, Fighting the Bears Ears Downsizing, Preservation Archeology Blog (June 28, 2019), https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/2019/06/28/fighting-the-bears-ears-downsizing-with-an-aged-friend/. ↑

- Dean B. Suagee, The Bears Ears National Monument Origin Story, American Bar Association (July 2, 2018), https://www.americanbar.org/groups/environment_energy_ \resources/publications/trends/2017-2018/july-august-2018/the_bears_ears_national/. ↑

- John C. Ruple, The Trump Administration and Lessons Not Learned from Prior National Monument Modifications, 43 Harv. Envtl. L. Rev. 1, 4 (2019); NRDC et al. v. Trump (Bears Ears), Nat. Resources Def. Council, https://www.nrdc.org/court-battles/nrdc-et-v-trump-bears-ears (last updated Nov. 30, 2020). ↑

- Sarah Krakoff, Public Lands, Conservation, and the Possibility of Justice, 53 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 213, 214 (2018) [hereinafter Krakoff II]. ↑

- Charles Wilkinson, “At Bears Ears We Can Hear the Voices of Our Ancestors in Every Canyon and on Every Mesa Top”: The Creation of the First Native National Monument, 50 Ariz. St. L.J. 317, 329 (2018). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Krakoff II, supra note 6, at 216. ↑

- Ruple, supra note 5, at 3. ↑

- Doelle, supra note 3. ↑

- Felicia Fonseca, Native American Tribes Call Trump’s Revamp of Tribal Advisory Commission a ‘Slap in the Face’, PBS News Hour (Dec. 11, 2017), https://www.pbs. org/newshour/politics/native-american-tribes-call-trumps-revamp-of-tribal-advisory-commission-a-slap-in-the-face. ↑

- Press Release, Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, Native American Tribes Condemn the Trump Administration’s Motives for Repealing Bears Ears National Monument (Mar. 5, 2018), http://bearsearscoalition.org/native-american-tribes-condemn-the-trump-administrations-motives-for-repealing-bears-ears-national-monument/. ↑

- See Martin Nie, The Use of Co-Management and Protected Land-Use Designations to Protect Tribal Cultural Resources and Reserved Treaty Rights on Federal Lands, 48.3 Nat. Resources J. 585, 606–07 (2008); Lauren Goschke, Tribes, Treaties, and the Trust Responsibility: A Call for Co-Management of Huckleberries in the Northwest, 27 Colo. Nat. Resources, Energy & Envtl. L. Rev. 315, 356–57 (2016). ↑

- Press Release, Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, supra note 13. ↑

- Krakoff II, supra note 6, at 226–27. ↑

- Wilkinson, supra note 7, at 321. ↑

- Krakoff I, supra note 1, at 135. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id.; Wilkinson, supra note 7, at 318. ↑

- Krakoff I, supra note 1, at 135; Wilkinson, supra note 7, at 318. ↑

- Ruple, supra note 5, at 18. ↑

- The Region to the Native Eye, Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, https://bearsearscoalition.org/the-region-to-the-native-eye/ (last visited Feb. 2, 2020). ↑

- Krakoff I, supra note 1, at 135. ↑

- Krakoff II, supra note 6, at 256. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Krakoff I, supra note 1, at 169. ↑

- Wilkinson, supra note 7, at 325; Who We Are, Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, https://bearsearscoalition.org/about-the-coalition/ (last visited Feb. 2, 2020). ↑

- Wilkinson, supra note 7, at 323–25. ↑

- Id. at 325. ↑

- Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, Proposal to President Barack Obama for the Creation of Bears Ears National Monument 6 (Oct. 15, 2015), https://bearsearscoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Bears-Ears-Inter-Tribal-Coalition-Proposal-10-15-15.pdf. ↑

- Nie, supra note 14, at 602; see also The Honorable Eric Smith, Some Thoughts on Comanagement, 14 Hastings W.-N.W. J. Envtl. L. & Pol’y 763, 767 (2008). ↑

- Ed Goodman, Protecting Habitat for Off-Reservation Tribal Hunting and Fishing Rights: Tribal Comanagement as a Reserved Right, 30 Envtl. L. 279, 343 (2000); Marren Sanders, Ecosystem Co-management Agreements: A Study of Nation Building or a Lesson on Erosion of Tribal Sovereignty?, 15 Buff. Envtl. L.J. 97, 106 (2008). ↑

- Goodman, supra note 33, at 283. ↑

- Sanders, supra note 33, at 107. ↑

- Goschke, supra note 14, at 354. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Nie, supra note 14, at 607. ↑

- Smith, supra note 32, at 767, 770. ↑

- See Nie, supra note 14, 608–16. ↑

- See Goschke, supra note 14, at 358 (providing examples for salmon management); Mary Ann King, Co-Management or Contracting? Agreements Between Native American Tribes and the U.S. National Park Service Pursuant to the 1994 Tribal Self-Governance Act, 31 Harv. Envtl. L. Rev. 475, 507–27 (2007) (providing examples for national park management); Nie, supra note 14, at 610–11 (provides examples for national forests); Sanders, supra note 33, at 131–63 (providing examples for salmon management, national forests management, and wolf management). ↑

- Nie, supra note 14, at 610. ↑

- Goschke, supra note 14, at 352. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Smith, supra note 32, at 780. ↑

- The Region to the Native Eye, Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, https://bearsearscoalition.org/the-region-to-the-native-eye/ (last visited Feb. 2, 2020). ↑

- Wilkinson, supra note 7, at 325–26. ↑

- Id. at 326. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Monument Map, Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, https://bearsearscoalition. org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/uw_BearsEars_Proclamation_8.5×11.pdf (last visited Apr. 26, 2020). ↑

- Id. at 325. ↑

- Krakoff II, supra note 6, at 247. ↑

- Krakoff I, supra note 1, at 162. ↑

- See Wilkinson, supra note 7, at 323. ↑

- Wilkinson, supra note 7, at 329. ↑

- Proclamation No. 9558, 3 C.F.R. 402, 407 (Dec. 28, 2016). ↑

- Wilkinson, supra note 7, at 229–30 (quoting Proclamation No. 9558, supra note 56, at 3). ↑

- Proclamation No. 9558, 3 C.F.R. at 407–08. ↑

- Id. at 408. ↑

- Id. at 408–09; Fonseca, supra note 12. ↑

- Proclamation No. 9558, 3 C.F.R. at 408. ↑

- Id. at 409; Wilkinson, supra note 7, at 331–32. ↑

- Proclamation No. 9558, 3 C.F.R. at 409; Wilkinson, supra note 7, at 331. ↑

- Proclamation No. 9558, 3 C.F.R. at 409; Wilkinson, supra note 7, at 331–32. ↑

- Restoring protections for Bears Ears National Monument, Grand Canyon Trust, https://www.grandcanyontrust.org/bears-ears-national-monument (last visited Feb. 2, 2020). ↑

- Krakoff II, supra note 6, at 250. ↑

- See Press Release, Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, Bears Ears Commissioners Selected, Focus on the Future of the National Monument (Mar. 17, 2017), https://bearsearscoalition.org/bears-ears-commissioners-selected-focus-on-the-future-of-the-national-monument/ [hereinafter Press Release, Focus on the Future of the National Monument]. ↑

- Wilkinson, supra note 7, at 331. ↑

- Press Release, Grand Canyon Trust, President Obama’s New Bears Ears National Monument Makes History (Dec. 28, 2016), https://www.grandcanyontrust.org/president-obamas-new-bears-ears-national-monument-makes-history. ↑

- Press Release, Focus on the Future of the National Monument, supra note 67. ↑

- See Michael A. Estrada, Protecting Sacred Land for the Next Generation: Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition’s Carleton Bowekaty, Hewlett Foundation (June 13, 2019), https://hewlett.org/protecting-sacred-land-for-the-next-generation-bears-ears-inter-tribal-coalitions-carleton-bowekaty/. ↑

- Ruple, supra note 5, at 22. ↑

- Exec. Order No. 13,792, 82 Fed. Reg. 20,429, 20,429 (Apr. 26, 2017). ↑

- Id. ↑

- See Ryan Zinke, Sec’y of Interior, Interim Report Pursuant to Executive Order 13792 (June 10, 2017) [hereinafter Zinke I]. ↑

- Id. at 4. ↑

- Fonseca, supra note 12. Benally’s opposition to the monument was based on concerns about, and distrust in, the federal government managing the historic tribal lands. See Rebeca Benally, Bears Ears National Monument designation disastrous for Utah grassroots Navajos, San Juan Record (Apr. 12, 2016); Rebecca M. Benally, Women in Government Leadership Program, Governing (2017), https://www.governing.com/gov-institute/wig/rebecca-benally.html. ↑

- Zinke I, supra note 75, at 5. ↑

- Press Release, Dept. of Interior, Secretary Zinke Submits 45-Day Interim Report on Bears Ears National Monument and Extends Public Comment Period (June 12, 2017), https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/secretary-zinke-submits-45-day-interim-report-bears-ears-national-monument-and-extends. ↑

- Ryan Zinke, Sec’y of Interior, Final Report Summarizing Findings of the Review of Designations Under the Antiquities Act 10 (Dec. 5, 2017) [hereinafter Zinke II]. ↑

- Id. at 11. ↑

- Krakoff I, supra note 1, at 165. ↑

- Id. at 166. ↑

- Proclamation No. 9681, 82 Fed. Reg. 58,081 58,082 (Dec. 4, 2017). ↑

- Id. at 58,086. ↑

- Id.; See Protecting Bears Ears National Monument, Native Am. Rights Fund, https://www.narf.org/cases/bears-ears/ (last updated Jan. 9, 2020) (discussing the disingenuous inclusion of Native American voices and interests in the reduction process). ↑

- Ruple, supra note 5, at 18. ↑

- Heather Smith, Shash Jáa National Monument Is an Insult, Say Tribes, Sierra (Feb. 2, 2018), https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/shash-j-national-monument-insult-say-tribes. ↑

- Press Release, Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, supra note 13. ↑

- Changes to Bears Ears National Monument Map, Grand Canyon Trust (Dec. 4, 2017), https://www.grandcanyontrust.org/changes-bears-ears-national-monument-map. ↑

- U.S. Const. art. I, § I. ↑

- Whitman v. Am. Trucking Ass’n, 531 U.S. 457, 472–73 (2001). ↑

- Perot v. Fed. Election Comm’n, 97 F.3d 553, 559 (D.C. Cir. 1996). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Nat’l Park and Conservation Ass’n v. Stanton, 54 F. Supp. 2d 7, 21 (D. D.C. 1999). ↑

- Id. at 19. The term subdelegation also refers to when an agency subdelegates to a subordinate federal officer or federal agency. Although the two issues are related, courts apply different standards to each situation. This Article is limited to subdelegations to outside entities. For a discussion of subdelegations to subordinate federal agencies, see Kobach v. U.S. Election Assistance Comm’n, 772 F.3d 1183 (10th Cir. 2014) and U.S. v. Widdowson, 916 F.2d 587 (10th Cir. 1900). ↑

- Nat’l Park and Conservation Ass’n, 54 F. Supp. 2d at 17. ↑

- Id. at 17-18. ↑

- Widdowson, 916 F.2d at 592 (overruled and vacated on other grounds by U.S. v. Widdowson, 502 U.S. 801 (1991)); see also Nat’l Park and Conservation Ass’n, 54 F. Supp.2d at 18; Am. Horse Prot. Ass’n, Inc. v. Veneman, 2002 WL 34471909, at *4–6 (D. D.C. 2002). ↑