Picture Alaska’s largest caribou herd, wild salmon, eleven major rivers, and Alaskan Native communities’ spiritual, cultural, and historic lands.[2] Now picture a 211 mile-long road cutting through that ecologically diverse landscape to reach a mining district that could put the entire area in peril with little to no economic gain.[3] That is the Ambler Mining District road project approved by the Bureau of Land Management (“BLM”) to traverse Gates of the Artic National Park and Preserve and state and tribal lands.[4] Several tribal and environmental groups have filed suit to challenge the BLM’s record of decision (“ROD”).[5] Among other claims, the lawsuit challenges the BLM’s National Historic Preservation Act (“NHPA”) and National Environmental Policy Act (“NEPA”) processes as inadequate.[6] Since their respective promulgations in 1970 and 1966, over 7,000 cases have been heard challenging the adequacy of NEPA[7] processes and nearly 1,000 challenging the adequacy of the NHPA[8] processes by federal agencies.

The intersection of NEPA’s Environmental Impact Statement analysis (“EIS”) and the NHPA’s Section 106 analysis (“Section 106”) fails to protect environmental and cultural resources, as well as to properly consult with Native American Tribes and engage in meaningful public participation. To address these failures, Congress should amend both statutes to require more rigorous tribal consultation and meaningful public participation. Additionally, Congress should adopt amendments requiring federal agencies to choose action alternatives with the fewest impacts on environmental and cultural resources. Congress should not only amend both statutes individually, but the Council of Environmental Quality (“CEQ”) should also require a stronger analysis through regulation when the statutes overlap. Under the current handbook guiding the integration of the two analyses, the statutes allow agencies to cut corners. While efficiency is an important aspect of the administration of the agencies, Congress should ensure the substantial purpose of the laws is implemented.

The nexus of the two laws, NEPA’s EIS analysis and the NHPA’s Section 106 analysis, showcase the shortcomings of the two separate laws and their inability, even in conjunction with one another, to protect resources, lands, and peoples.[9] The Biden Administration will surely promulgate more progressive and environmentally protective procedures, rules, and statutes.[10] The appointment of cabinet members, such as Deb Haaland as the Secretary of the Department of the Interior,[11] certainly gives us hope, but the promise of better administrative policy does not fix the failures of our “Magna Carta” environmental and historic preservation laws.[12]

Despite their initial intent, the existing NEPA and NHPA statutes still fail to protect the environment and cultural resources and to provide tribal governments decision-making powers.[13] The Final EIS[14] issued by the BLM in favor of the Ambler Mining Road demonstrates how NEPA and the NHPA interact and the failure of both in their intersection to protect tribal, state, and federal lands, including the Gates of the Arctic National Park.

This note proceeds as follows: Part I discusses the history and legal framework of NEPA, the NHPA, and their intersection. Part II analyzes the shortcomings of NEPA and the NHPA and the failures they impose on their intersection. Part III suggests statutory amendments and regulatory changes to strengthen the intersection of NEPA and NHPA processes.

NEPA and the NHPA are both referred to as the “Magna Carta” and “most important” statutes of their respective fields.[15] Both intricate statutes, the EIS and Section 106 analyses each deserve a separate breakdown. This section will explain the backgrounds and statutory components of first, NEPA, second, the NHPA, and third, their intersection.

NEPA,[16] signed into law by President Nixon on January 1, 1970,[17] requires federal agencies to assess environmental impacts of their actions in their decision-making processes.[18] Congress outlined the purpose of the statute to promote efforts to prevent damage to the environment, encourage public health and understanding of natural resources, and establish the CEQ.

Of most importance, NEPA “authorizes and directs that, to the fullest extent possible . . . all agencies of the Federal Government shall”:[19]

[I]nclude in every recommendation or report on proposals for legislation and other major Federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the human environment, a detailed statement by the responsible official on— (i) the environmental impact of the proposed action, (ii) any adverse environmental effects which cannot be avoided should the proposal be implemented, (iii) alternatives to the proposed action, (iv) the relationship between local short-term uses of man’s environment and the maintenance and enhancement of long-term productivity, and (v) any irreversible and irretrievable commitments of resources which would be involved in the proposed action should it be implemented.[20]

Not only does the statute hold all federal agencies accountable for drafting EISs for “major Federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the human environment,”[21] but it also requires “the responsible Federal official [to] consult with and obtain the comments of any Federal agency which has jurisdiction by law or special expertise with respect to any environmental impact involved.”[22]

NEPA remains a largely procedural statute that outlines multi-step processes for federal agencies to follow in their environmental analyses of proposed actions.[23] The CEQ regulations outline this multi-step process.

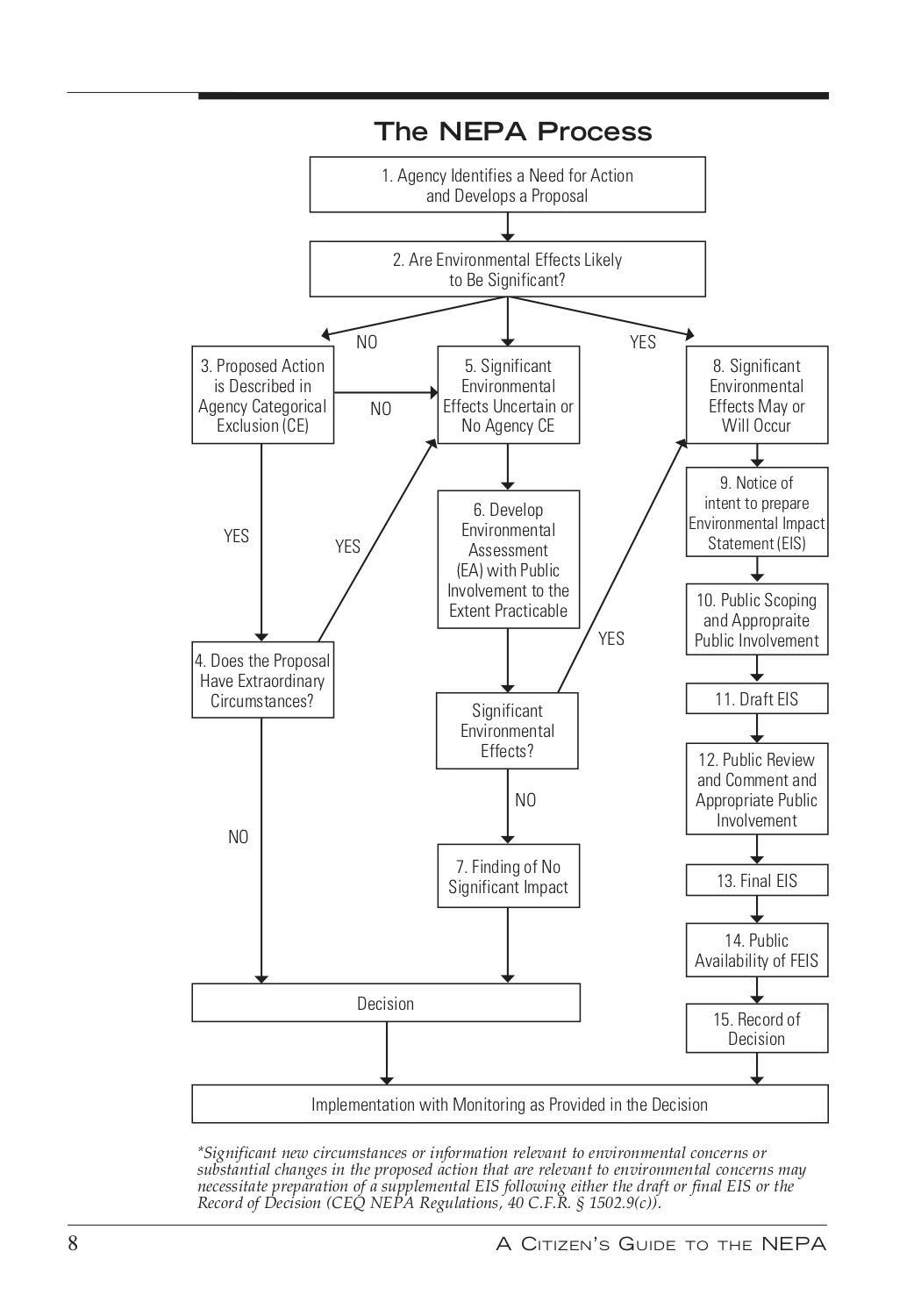

First, an agency must determine whether its action is “major” and initiate the planning process in its action proposals. All cooperating agencies involved must be identified and a lead agency chosen to ultimately be responsible for complying with NEPA. An agency must then determine whether its action qualifies as a categorical exclusion (“CE”) because it “does not individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the quality of the human environment.”[24] However, if the action does not qualify as a CE, then the agency must determine whether to prepare an Environmental Assessment (“EA”) or an EIS. An EA is a concise document that assesses environmental impacts and action alternatives to determine whether an EIS is necessary.[25] If the action will not have a significant effect, the agency will issue a Finding of No Significant Impact (“FONSI”).[26] If the action will “have a significant effect on the quality of the human environment,” then the agency must prepare a Draft EIS outlining: purpose and need; action alternatives; proposed alternative; and an analysis of direct, indirect, and cumulative effects.[27] After a public comment period, the lead agency will publish a Final EIS and then an ROD, which finalizes the EIS process and discusses mitigation measures.[28] See a flow chart of the NEPA process below:

Figure 1. Diagram of the NEPA EIS Process[29]

Figure 1. Diagram of the NEPA EIS Process[29]

Despite a trend toward reducing the substantive power of NEPA,[30] Executive Order 12898, under Clinton’s administration, requires that,

[t]o the greatest extent practicable and permitted by law . . . each Federal agency shall make achieving environmental justice part of its mission by identifying and addressing, as appropriate, disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of its programs, policies, and activities on minority populations and low-income populations in the United States and its territories and possessions. . . .[31]

This executive order instructed the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”), empowered by NEPA, to incorporate environmental injustice issues into their EIS considerations.[32] More pertinent to this article, the CEQ regulations require that federal agencies “integrate the NEPA process with other planning at the earliest possible time to ensure that planning and decisions reflect environmental values, to avoid delays later in the process, and to head off potential conflicts.”[33] This pushes agencies to incorporate historical preservation planning under the NHPA into the NEPA process.

The 2020 Trump Administration CEQ regulations (“2020 Regulations”) gut NEPA’s procedural requirements.[34] The redlined version shows many detrimental alterations, from retracting the meaning of “effects” and eliminating the requirement to consider cumulative impacts.[35] The 2020 Regulations diminish NEPA even further, following precedent that has shrunk the substantive ideals of the landmark environmental law.[36] The 2020 Regulations: (1) shorten the time limits to prepare EAs and EISs to a mere year, as opposed to the multi-year drafting and notice and comment periods that have historically been the norm in the analyses; (2) alter the definitions of “major” and “significant”; (3) alter the definition of “reasonable alternatives”; (4) increase identified categorical exclusions; (5) shorten the comment period requirements and prohibit accepting late comments despite reasoning; and (6) prohibit agencies from implementing stricter guidelines than the CEQ’s.[37]

In summary, the NEPA process requires environmental analyses for major actions significantly impacting the human environment, resulting in a CE, FONSI from an EA, or ROD from an EIS. EISs, the most robust of the analyses, include a statement of purpose and need and an analysis of action alternatives; proposed alternatives; and direct, indirect, and cumulative effects. NEPA’s EIS requirement is paralleled by the NHPA’s Section 106 analysis for impacts. While the acts diverge in many ways, the two analyses can, and are encouraged to, combine.[38]

Signed into law in 1966, the NHPA[39] stands as the flagship federal historic preservation law.[40] Congress enacted the law because “the preservation of [the United States’] irreplaceable heritage is in the public interest so that its vital legacy of cultural, educational, aesthetic, inspirational, economic, and energy benefits will be maintained and enriched for future generations of Americans.”[41] The NHPA Section 101 (“Section 101”) authorizes the Secretary of the Interior to establish the National Register of Historic Places and created the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (“ACHP”).[42] The Department of the Interior’s National Register of Historic Places regulations require consideration of

[t]he quality of significance in American history, architecture, archeology, engineering, and culture is present in districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects that possess integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association and[:] (a) that are associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history; or (b) that are associated with the lives of persons significant in our past; or (c) that embody the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction, or that represent the work of a master, or that possess high artistic values, or that represent a significant and distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction; or (d) that have yielded, or may be likely to yield, information important in prehistory or history.[43]

While Section 101 is important, the Section 106 analysis serves as the crux of historic preservation and protection from federal actions. Section 106 requires that agencies with “proposed Federal or federally assisted undertaking . . . take into account the effect of the undertaking on any district, site, building, structure, or object that is included in or eligible for inclusion in the National Register.”[44] Section 106 analyses require a report for federal “undertakings” “on any district, site, building, structure, or object that is included in or eligible for inclusion in the National Register.”[45] Mirroring a NEPA EIS, this analysis requires a report on the effects the undertaking will have on National Register listings and eligible areas and requires consultation with the applicable ACHP.[46] These councils include the local State Historic Preservation Office (“SHPO”) and Tribal Historic Preservation Office (“THPO”).[47] The Department of the Interior regulations explain that the Section 106 process exists to consult agencies with historic preservation concerns in federal undertakings, to avoid and minimize adverse effects on historic properties.[48] Because of the resources at stake and timing of the federal undertakings, “[t]he agency official shall ensure that the Section 106 process is initiated early in the undertaking’s planning, so that a broad range of alternatives may be considered during the planning process for the undertaking.”[49] While a lead agency must be identified, the agency may utilize consultants to prepare the Section 106 analysis.[50]

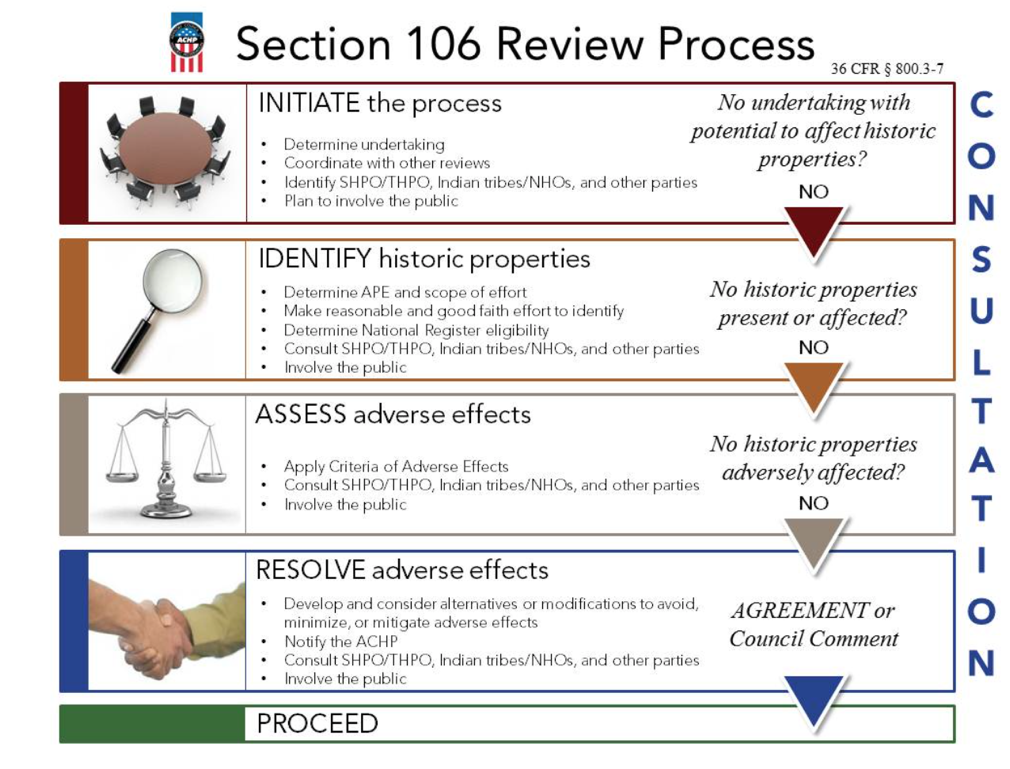

In initiating the process, a lead agency must be identified as responsible for NHPA compliance throughout the duration of the project analysis.[51] The lead agency must then (1) establish an undertaking, (2) coordinate with other reviews, such as NEPA, (3) identify and consult with the appropriate SHPO and/or THPO, (4) provide notice and a comment period to the public, (5) identify historic properties, (6) assess adverse effects, and (7) provide resolution of adverse effects.[52]

One of the most important requirements ensures that lead agencies notify applicable SHPOs and applicable THPOs of upcoming project plans and involve them early in the decision-making process.[53] Department of the Interior regulations require “[c]onsultation with an Indian tribe must recognize the government-to-government relationship between the Federal Government and Indian tribes.”[54] The lead agency must also involve the public in a notice and comment period.[55]

In 1971, President Nixon issued Executive Order 11593 for the Protection and Enhancement of the Cultural Environment, in furtherance of NEPA and the NHPA, which required federal agencies to direct their policies and programs in a manner that preserves, restores, or maintains the historical, architectural or archaeological significance of federally owned sites.[56] With this executive order, the Nixon Administration kicked off a longstanding practice to coordinate the NHPA and NEPA processes.[57] Over two decades later, President Clinton released the 1996 Executive Order 13007 protecting tribal religious sites.[58] The 1996 executive order declared that all federal public land agencies “shall, to the extent practicable, permitted by law, and not clearly inconsistent with essential agency functions, (1) accommodate access to and ceremonial use of Indian sacred sites by Indian religious practitioners and (2) avoid adversely affecting the physical integrity of such sacred sites.”[59] This executive order expanded federal government policy to consider tribal interests and increased tribal consultation requirements.

The Section 106 process remains simple, and the analyses result in findings of “ ‘no historic properties affected,’ ‘no adverse effect,’ or ‘adverse effects’ resolved through avoidance, minimization, or mitigation.”[60] The following diagram represents the NHPA Section 106 process.

Figure 2. Section 106 Review Process Flow Chart.[61]

Figure 2. Section 106 Review Process Flow Chart.[61]

Intersection of NEPA and the NHPA

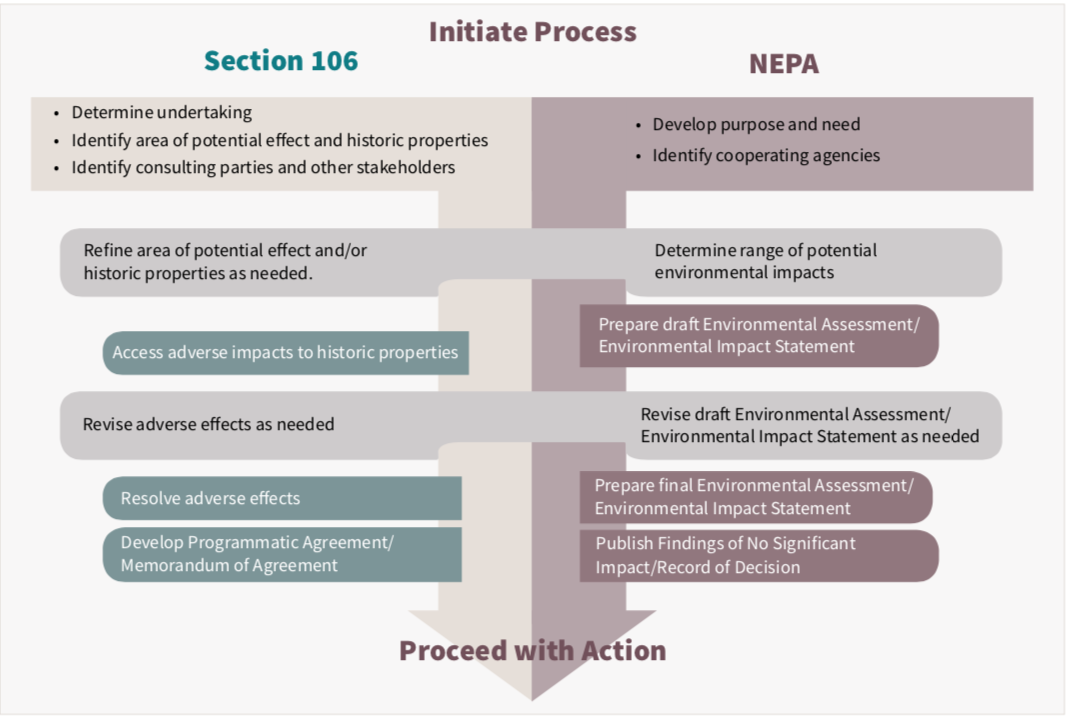

Regulations under Section 106 promulgated in 1999 require “[c]oordination with the National Environmental Policy Act.”[62] These regulations call for early integration and consideration of undertakings’ likely effects on historic properties during the agency’s deliberation over whether action is “major” and significantly affects the human environment.[63] The regulations allow for NEPA EIS, FONSI, and ROD reports to substitute for Section 106 paperwork.[64] The CEQ recognized the interconnected nature of the NEPA and the NHPA and released a handbook in 2013, in conjunction with the ACHP, to guide their integration.[65] NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook for Integrating NEPA and Section 106 (“Handbook”) acknowledges that both acts’ language encourage integration with one another.[66] The Handbook recognizes NEPA and the NHPA as “stop, look, and listen” statutes that require federal agencies to analyze their actions “before making decisions that might affect historic properties as one component of the human environment.”[67]

NEPA requires review of effects on the human environment, including “aesthetic, historic, and cultural resources as these terms are commonly understood, including such resources as sacred sites[,]” while the NHPA requires review of properties listed, or that are eligible for listing, on the National Register.[68] The actions also differ in identifying federal actions versus undertakings, and in considering the human environment versus National Register listed or eligible sites, districts, and properties.[69] To integrate the two statutes’ more substantive differences, the Handbook outlines how to “coordinate the processes” and how to “substitute” the processes.[70]

1. Coordination of the Processes

The coordination of the processes can be difficult because NEPA and the NHPA have different public participation and tribal consultation requirements. Because NEPA allows for three different avenues (CEs, EAs, and EISs), public participation and tribal involvement look different even within each avenue of NEPA.[71] With CEs, there is hardly any public participation, and with EAs it is at the discretion of the individual agency officer, but for EISs, consultation and notice and comment periods on the draft EISs are required.[72] On the flip side, Section 106 has less public participation, but has more consultation-based analysis than NEPA’s EIS. Its mission statement establishes that the analysis “seeks to accommodate historic preservation concerns with the needs of Federal undertakings through consultation among the agency official and other parties with an interest in the effects of the undertaking on historic properties.”[73] Under NEPA, agencies are encouraged, but not required, to involve Indian tribes early and to consult with them as cooperating agencies.[74] Because consultation with tribes is mandatory under Section 106, but only encouraged under NEPA, Section 106 will likely always have more stringent consultation requirements.[75] Executive Order 13175, Consultation and Coordination with Indian Tribal Governments, sets out that “in determining whether to establish Federal standards, [the agency should] consult with tribal officials as to the need for Federal standards and any alternatives that would limit the scope of Federal standards or otherwise preserve the prerogatives and authority of Indian tribes.”[76] The executive order also requires “each agency [to] have an accountable process to ensure meaningful and timely input by tribal officials in the development of regulatory policies that have tribal implications.”[77]Another executive order, 12898: Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations, signed by President Clinton in 1994, peripherally expanded avenues in which agencies can be held accountable for tribal consideration. Because many tribal populations fall into low-income communities,[78] the executive order could be applied to increase consultation and inclusion efforts. The order states:

[t]o the greatest extent practicable and permitted by law . . . each Federal agency shall make achieving environmental justice part of its mission by identifying and addressing, as appropriate, disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of its programs, policies, and activities on minority populations and low-income populations[.][79]

NEPA requires agencies “to describe the environment, including cultural resources . . . and to discuss and consider the environmental effects of the proposed action and alternatives, so decision makers and the public may compare the consequences associated with alternate courses of action.”[80] Conversely, Section 106 requires agencies “to make a reasonable and good faith effort to identify historic properties.”[81] NEPA analyses conclude with “a CE, a FONSI for EAs, or a ROD for EISs, or a No Action decision.”[82] Section 106 concludes with “no historic properties affected;” “no adverse effect;” or “adverse effect” in either an MOA or PA.[83]

NEPA compliance through a CE does not meet Section 106 requirements.[84] CEs are specific categories of actions that the agency has determined do not have adverse effects on the human environment.[85] This includes actions such as minor facility renovations or trail reconstruction.[86] When the agency identifies an action as falling into one of these categories, the agency halts environmental analysis.[87] Because the agency halts analysis at this stage, it would not meet the consultation requirements of Section 106.[88] If the agency recognizes a CE under NEPA, it must continue the Section 106 analysis.[89] If the agency, in consultation with the SHPO or THPO, finds “no adverse effect,” then the agency can proceed with the CE.[90] If the agency finds that there may be an “adverse effect” on historic properties, it must then analyze whether to proceed under an EA or EIS due to “extraordinary circumstances.”[91]

In an EA, NEPA leaves public participation at the agency’s discretion while Section 106 always requires it.[92] EAs are essentially baby EISs that analyze the extent of the significance of the environmental effects of an action and determine whether an EIS is necessary.[93] The lack of public participation leaves the analysis short of meeting Section 106’s requirements for consultation and public participation.[94] The Handbook suggests that a comprehensive communication plan that meets Section 106 and EIS requirements is most desirable, even in an EA analysis.[95] The Handbook suggests that to meld the two statutes in an EA, the agency should “use the Section 106 adverse effect criteria in evaluating and describing effects on historic properties . . . [and] relate adverse effects under Section 106 to the criteria for determining the significance of impacts under NEPA.”[96] If a FONSI is issued, agencies must conclude the Section 106 process with an MOA or PA and require mitigation efforts.[97] Neither NEPA nor Section 106 requires an EIS just because of potential adverse effects to a historic property.[98] Thus, agencies must determine whether effects on the historic properties will lead to “significant” environmental effects and trigger EIS review.[99]

The Handbook recommends coordinating the two analyses during the Purpose and Need stage so that the public, tribes, and cooperating agencies can be fully included.[100] The Purpose and Need stage is the initiation of the project, where the lead agency drafts a statement describing what it is trying to achieve with the action.[101] By coordinating the analyses as early as the Purpose and Need stage, the processes can be fully fleshed in the stated goals of the action. The Handbook states “[t]he agency should clearly describe the form and format of public meetings, hearings, or listening sessions, and clarify that Section 106 will be coordinated with the EIS process; including how and when that coordination will take place.”[102] Agencies should remember that “ ‘cultural resources’ that are to be identified and assessed as part of the affected environment include a broader array of properties than the ‘historic properties’ defined in Section 106.”[103] The agency should include all consultation information not protected in the draft EIS to ensure that THPO and SHPO consultation is reflected in every alternative considered.[104] Section 106 requires specialized historic studies, and the agency should include these in each EIS alternative.[105] The Handbook briefly addresses public comment integration by suggesting that EIS public comment periods should meet Section 106 public notification requirements, and reminds agencies that if mitigation measures are required in a ROD, they must also be memorialized in a Section 106 MOA or PA.[106]

In summary, the processes can be coordinated with special attention to meeting the tribal consultation, public participation, and historic site identification requirements of each act. According to the Handbook, the coordination of processes is easiest when the NEPA analysis is undergoing a fully-fledged EIS, instead of a CE or EA. However, coordination is also possible in CEs when SHPOs and THPOs find no adverse effects and in EAs when public participation is commenced.

2. Substitution of the Processes

While coordination is always necessary, complete substitution of the NEPA review and Section 106 analyses is sometimes possible.[107] Substitutions mean that only one analysis is applied—NEPA EIS or Section 106—but not both. Substitutions are only appropriate for EAs and EISs (not CEs) and the ACHP and THPO or SHPO must be notified promptly of the decision to substitute the documents.[108] Substitution makes the most sense with complex and major Section 106 issues that can incorporate into an EIS instead of requiring more paperwork and process.[109] The federal agency must be actively involved in the preparation of the EIS if substitution is used because Section 106 requires federal agency prepared materials, whereas NEPA allows for contractors.[110] The substitution process is intended to save time and documentation, and provide a clear, concise overview of the project to the public.[111] To properly substitute the processes, federal agencies must: (1) notify ACHP and the SHPO/THPO in advance; (2) identify consulting parties during the NEPA scoping process; (3) identify historic properties and involve the public; (4) consult SHPO/THPO on effects; (5) resolve adverse effects to historic properties; (6) provide opportunity for review and objection by SHPO/THPO; (7) terminate the substitution process if it is “no longer prudent”; and (8) conclude the substitution process with an ROD, MOA, or PA.[112]

Figure 3. Intersection of NEPA and THE NHPA Section 106 Analyses.[113]

Failures of NEPA, THE NHPA, and Their Intersection

NEPA and the NHPA both fail in their own capacities, but the intersection of the two statutes highlights their major downfalls even more acutely. This section addresses: concerns with NEPA; concerns with the NHPA; and concerns with their intersection.

Concerns with and Suggestions for NEPA

NEPA came under scrutiny on its fiftieth birthday.[114] The National Association of Environmental Professionals analyzes the success of EISs throughout each year. In 2019, it found eighty-seven percent of EISs conducted were inadequate in their analysis.[115] There have been efforts to restructure NEPA in the past, but most have failed—or at least failed to provide any true change.[116] NEPA has several shortcomings which are analyzed in this section: (1) the lack of substantive requirements; (2) the lack of meaningful public engagement; (3) the weak tribal consultation requirements; and (4) the poor coordination between federal, state, and tribal offices.

- NEPA Lacks Substantive Weight.

The loss of substantive powers of NEPA have reduced the statute to procedural power.[117] While organizations have found creative ways in which to continue utilizing NEPA as a successful litigation and policy tool to hold agencies accountable for their EIS decision-making processes, the statute needs to have its substantive purpose and power reinstated. With this sentiment, NEPA could be reformed to look more like some of the states’ “mini-NEPAs.” Minnesota’s state-level environmental impact analysis law actually has substantive powers in its statement:[118]

No state action significantly affecting the quality of the environment shall be allowed, nor shall any permit for natural resources management and development be granted, where such action or permit has caused or is likely to cause pollution, impairment, or destruction of the air, water, land or other natural resources located within the state, so long as there is a feasible and prudent alternative consistent with the reasonable requirements of the public health, safety, and welfare and the state’s paramount concern for the protection of its air, water, land and other natural resources from pollution, impairment, or destruction. Economic considerations alone shall not justify such conduct. [119]

Unlike NEPA, Minnesota’s state-level environmental impact analysis law actually requires implementation of feasible alternatives, rather than just consideration and reasonable explanation for not choosing the alternative.[120] Additionally, other state “mini-NEPAs” have purpose statements that show strong intent to provide public participation opportunities. For example, Massachusetts’s environmental policy act outlines its purpose as being “to provide meaningful opportunities for public review of the potential environmental impacts of Projects for which Agency Action is required[.]”[121] With the purpose statement focusing on public participation, public participation issues are more likely to be upheld in court decisions as falling within the legislative intent. Further, California courts have taken a similar provision in the California statute to strictly require public participation.[122] Massachusetts also provides the opportunity for citizens to petition the government to require the preparation of an Environmental Notification Form—similar to an EA.[123]

Multiple Supreme Court cases have stripped the heralded statute of its substantive power. In Vermont Yankee, the Supreme Court stated that NEPA only imposes “essentially procedural” requirements upon agencies;[124] in Strycker’s Bay Neighborhood Council, Inc., the Supreme Court held that it can only ensure that the agency considered the environmental consequences—nothing more;[125] and in Methow Valley Citizens Council, the Supreme Court confirmed that NEPA “does not mandate particular results” and does not require agencies to mitigate adverse effects.[126] These cases and more have left environmental groups little to go on but procedural claims.

- NEPA’s Public Engagement is Not Meaningful.

NEPA’s public engagement is not meaningful under the current statute because: (1) it starts too late in the process; (2) lacks enough participation opportunities; (3) does not provide enough hearings; (4) does not provide long enough comment periods; and (5) only provides overwhelmingly long, technical, and inaccessible documents for the public to engage. One researcher sums it up that NEPA “does not incorporate the opinions of stakeholders as much as it relies on the findings of science-based studies.”[127] Science is a powerful tool in the NEPA process, but the scientific studies cited need to be challenged and discussed amongst stakeholders and the general public.

To start, the statute only requires notice and comment for EIS reviews, not CE or EA reviews.[128] This prevents the public from ever bringing up points that could have shown the need to conduct a full-blown EIS in the first place. On top of preventing possible identification of adverse effects, it also prevents public participation from starting early enough in the process to be meaningful. Public participation should start early in the process, but instead, the paper tiger lives for years before ever even notifying the public of its existence.[129] This inaccessibility to information prevents its use in key decisions. In the time before public participation is required, the agency can decide a CE applies, decide an EIS is unnecessary, or fully flesh out the draft EIS including the alternatives—all without ever getting input from locals and the public. Even in EIS notice and comment procedures, public participation is typically not meaningful.[130] The Handbook only requires NEPA public and comment periods, but clear criteria should be established to determine the public involvement required in individual projects—leaning towards expansive and meaningful public participation requirements.[131]

- NEPA’s Tribal Consultation is weak.

Meaningful tribal consultation is currently not mandatory under NEPA,[132] but it should be required to foster a stronger consultation process in conjunction with the NHPA. The new CEQ rules specifically prohibit agencies from implementing stricter EIS and assessment requirements.[133] Despite tribes wanting a voice at the table, tribal involvement is often nonexistent because consultation is not mandatory, the 1994 executive order is not mandatory,[134] and public participation often does not reflect a meaningful engagement process.[135] However, Tribes and States should step in with additional legislation that supports tribal engagement.

- Coordination of Processes Between Federal, State, and Tribal Offices is Poor.

While NEPA only applies to federal agency actions, state and tribal expertise and authority are almost always implicated.[136] To better situate themselves, the federal agencies should implement shared sovereignty principles that encourage effective communication and cooperation between agencies, states, and tribes so that all angles of the issues may be identified and addressed.[137]

Overall, the NEPA analysis lacks substantive requirements, does not provide for meaningful public comment or tribal consultation, and thus falls short as a tool for the protection of both environmental and natural resources and historical and cultural resources.

The Trump Administration altered the original CEQ[138] rules governing the use of NEPA in its promulgation of new CEQ rules in September of 2020.[139] The Trump CEQ rules weaken the cumulative impacts analysis requirement in the face of multifaceted climate change issues; narrow the purpose and scope mission; narrows the definitions of “major,” “significant,” “reasonable alternatives and effects;” and increase the list of categorical exclusions available for agencies to avoid environmental review of their actions.[140] Procedurally, the Trump rules prohibit the acceptance of late comments.[141] This amendment is especially harsh in the wake of COVID-19 issues which hamper the ability to meaningfully engage in the process.[142] These restrictive processes fall far short of the 2007 CEQ guidance to assist individuals in making the public’s “voice heard” in the NEPA process.[143]

A group of twenty-three attorney generals filed a lawsuit challenging the Trump administration’s “unlawful, unjustified, and sweeping revisions” to the CEQ rules overseeing NEPA.[144] California, et. al, mentions “NEPA’s public process also provides vulnerable communities and communities of color that are too often disproportionately affected by environmental harms a critical voice in the decision-making process on actions that threaten adverse environmental and health impacts.”[145] Environmental organizations across the nation also filed suit against the CEQ.[146] These claims acknowledge the environmental injustices that the new CEQ rules threaten to the nation’s vulnerable communities. Another complaint, Wild Virginia, et. al v. CEQ,[147] filed in August 2020, accused the CEQ of cutting corners and disregarding evidence from the past forty years of implementation and input from citizens and industries.[148] The Biden Administration will likely revoke the Trump-era rules, but nonetheless, these rule changes highlight the vulnerabilities of the statute.[149] In conjunction with the NHPA, the two processes stand little chance at full protection of cultural resources, historic properties, and tribal communities.

Concerns with and Suggestions for THE NHPA

The NHPA also came under scrutiny on its fiftieth anniversary, with the U.S. Forest Service analyzing its own enforcement of the law.[150] To uphold the law, federal agencies should incorporate public participation and tribal consultation as early in the process as possible.[151] Historic preservation throughout the years has become stuck in its ways, but the NHPA has the opportunity to evolve with today’s focus on and understanding of environmental justice issues in conjunction with the need to protect history.[152] Similar to NEPA, the NHPA’s shortcomings include: (1) a focus on historic properties over cultural resources; (2) the lack of meaningful public engagement; (3) the weak tribal consultation requirements; and (4) the poor coordination between federal, state, and tribal offices.

- The NHPA Focuses on Historic Properties over Cultural Resources.

In their application of the NHPA, most agencies have focused on the protection of the built environment and the historic properties listed on the National Register, as opposed to cultural resources.[153] The statute allows for this narrowly focused approach and dishonors the goal of protecting cultural and religious sites, especially those of tribes.[154] The act itself is purely advisory, so federal agencies do not necessarily have to implement ACHP suggestions, other than accounting for adverse effects.[155] This leads to adverse impacts to heritage resources.[156] Additionally, the inflexibility of the nine listing criterion[157] makes it difficult to include objects, buildings, and properties that reflect changing values that warrant the need for their cultural and historic preservation.[158] As in the Ambler Mining District Access Road Project, many cultural sites for the local tribes are not eligible for the National Register, and are thus not protected despite their cultural value.[159] Even if the site qualifies as a traditional cultural site[160]—which requires “association with cultural practices or beliefs of a living community that (a) are rooted in that community’s history; and (b) are important in maintaining the continuing cultural identity of the community”[161]—it might not be eligible for the National Register because it does not meet the stringent requirements to be listed.[162] This could be for a number of reasons. For religious and protective reasons, tribes might need to keep their sites in secrecy. The National Register requires identification of the site and its boundaries, so when there is a desire to keep the site location secret, an impossible problem arises for those tribal leaders who seek to protect their cultural site both through the NHPA and through general ideologies of secrecy.[163] Further, many of these sacred sites need protection for their religious value, but because the NHPA focuses on historic value, rather than cultural or religious, tribes must make the case for the historic significance instead.[164]

While Section 106 does require public notification, it does not require a public notice and comment period, as the EIS process does.[165] Because the focus is truly on SHPO and THPO consultation,[166] this is somewhat understandable, but modern regulations should recognize the benefit in having assistance with the public identifying historic properties and analyzing the potential for adverse effects. For a seamless process, and to ensure meaningful engagement and identification of historic properties—even if the NEPA review is only in a CE or EA review—the NHPA should mandate a public notice and comment period. Additionally, the NHPA does not expressly provide a private cause of action against the federal government.[167] A private cause of action is crucial for meaningful public engagement and environmental justice work.[168] For example, the Clean Air Act provides for “citizen suits,” which gives “any person” the power to request the court system to hold the agency accountable for enforcing the law or regulating.[169] The Clean Water Act provides a similar citizen suit provision. Citizen suit provisions enhance public participation by encouraging groups and individuals to participate in the process and hold their administrators accountable.[170] They provide a sense of autonomy and control that does not exist without the right to a private cause of action. They also give the ability to be heard and provide a stronger incentive for administrators to follow procedural public participation requirements.[171]

While citizens can address these issues under the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”),[172] standing is much easier to achieve if a citizen suit provision applies to “any person” and also does not provide the “extreme deference” to agencies as does the APA.[173] Without this power, the public participation requirements only require agencies to consider the public comment—but not actually to listen to it. The tool of a citizen suit provides the public with security that their opinions and participation matter in a meaningful way and that they have the opportunity to see their desires through. This lack of meaningful engagement and inflexibility shows why the National Register of Historic Places does not yet reflect America’s diverse history, and thus does not protect those diverse resources in Section 106 and EIS analyses.[174] This failure to acknowledge diverse historic and cultural resources spills into other aspects of upholding the act, such as the dismal reality of tribal consultation.

The application of the NHPA on tribal lands has many issues.[175] Tribal consultation has historically been weak, nonexistent, or ad hoc under the NHPA.[176] In her promotion of more meaningful tribal consultation, Amanda Marinic, called for “Congress [to] amend the NHPA to require that a federally-approved or funded project . . . not have any adverse effects on a cultural or religious site . . . to move forward, unless all . . . involved parties agree to move forward despite . . . adverse effects.”[177] Others call for better tribal consultation as the only feasible solution to the dilemma of federal agencies’ finding a Hobson’s choice between abandoning their projects or violating the NHPA.[178] The 1992 amendments that increased the role of tribes are still inadequate.[179] Some are calling for legislative exemptions from tribal consultation for federal agency actions on federal lands—this route is unacceptable and would only heighten already existing tensions and inadequacies of the NHPA.[180] The vagueness of the NHPA’s tribal consultation processes results in conflicts between the agencies and the tribes, leaving neither satisfied.[181] A firmer outline of tribal consultation will make the process more equitable, producing better long-term decisions by federal agencies regarding tribal property.

The Handbook allows for substitutions to prevent duplication but provides no guidelines for tribal, state, and federal agencies to work in tandem throughout their processes.[182] Parallel to society’s growing focus on local, regional, national, and global collaboration for climate change responses,[183] it is paramount for environmental, historical, and cultural protection for tribal, state, and federal agencies to work together in identifying alternatives and ultimately deciding project actions to pursue. Although less complicated than NEPA, the NHPA has its own intricacies and its own faults. The ACHP needs to enforce its tribal consultation mandate, require public comment periods for all Section 106 analyses, and ensure that cooperating agencies are involved in the historic property and consultation processes.

Case Study: Ambler Mining District Road

The BLM, in partnership with the Army Corps of Engineers and U.S. Coast Guard, approved a Final EIS for Ambler Road access through state, federal, and tribal lands in Alaska, including the Gates of the Arctic National Refuge.[184] The Ambler Road Project was not subject to the new CEQ regulations because it had already been proposed and largely decided before the establishment of the new rules.[185] Thus, the project serves to show the inadequacies of the base NEPA and NHPA analyses nexus. Because the project runs through state, federal, and tribal lands, it serves as a perfect example of multiple-level agency coordination. Its tribal and federal lands host a spattering of cultural resources and National Register eligible properties, including over 323 archeological or historic sites ranging from prehistoric habitations to historic mining cabins.[186] As is frequently the case in NEPA and Section 106 analyses, the SHPO and THPO were not formally consulted before a draft EIS was released.[187] This resulted in a lack of protection of cultural resources, led to the decision for tribes to file suit, and showcases the need for the strengthening of not only the NHPA but the intersection of NEPA and the NHPA.[188]

Suggestions For The Future of The Intersection of NEPA And THE NHPA

While the two statutes have similar issues on their own, the overlap of NEPA and the NHPA highlights concerns regarding meaningful public participation, tribal consultation, and coordination between cooperating agencies and sovereign entities.[189] The NEPA–NHPA nexus does not only need to be streamlined, it needs to be completely reworked to ensure successful protection of cultural resources, historic properties, and tribal self-autonomy. Congress, the CEQ, and the ACHP need to amend NEPA environmental reviews and NHPA Section 106 analyses to: (1) foster true coordination between NEPA and NHPA Section 106 processes, preventing the reduction of oversight; (2) promulgate rules that demand tribal consultation in the NEPA EIS process and clearly integrate the NHPA and NEPA tribal consultation processes; (3) require more meaningful public participation processes in which the project timeline and approval process relies more heavily on; and (4) create direct communication between federal, state, and tribal offices and mandate that they consult with each other.

Foster More Robust Coordination Between NEPA and the NHPA Section 106 Processes.

While the CEQ released a handbook in 2013[190] to outline the coordination of the processes, coordination, as it stands today, allows for oversight of key issues and does not fully integrate the purpose of each statute. The Handbook recognizes that “[t]he timing of the decision to pursue a substitution approach is extremely important,” and that determining whether to substitute or coordinate is often a difficult decision.[191] The CEQ and the ACHP need to reconvene to promulgate policy guidelines that outline a more rigid process for substitution and encourage more coordination between all agencies in conducting NEPA and NHPA analyses on the same project.

Promulgate Rules That Demand Tribal Consultation In The NEPA EIS Process And Clearly Integrate The NHPA And NEPA Tribal Consultation Processes

Tribal consultation under NEPA and the NHPA has been “merely good words” in most federal agencies’ pasts.[192] While tribal consultation processes can be enforced through the separate statutes, guidance on the integration of the two statutes should be incorporated to prohibit overlapping process from moving forward without tribal consultation.

The Handbook recognizes that “[a] good working relationship with the relevant SHPO or THPO will help the substitution approach move forward more smoothly. Consider any agency-specific policies or practices that might complicate the process, such as delegation to local governments or applicants to act in the Federal agency’s stead.”[193] The Handbook itself acknowledges the importance of tribal consultation, hinting at the downfall of the entire process if tribal consultation is not clearly integrated.[194] The Handbook, however, does not provide a formula on how to consult with local governments and tribes, nor does it provide a timeline. NEPA and the NHPA should both require tribal consultation and outline the timeline and process so that federal agencies are held more accountable.

Require More Meaningful Public Participation Processes

In addition to increased requirements for tribal consultation, the public at large should be more included in federal agencies’ analysis and decision-making process. Although NEPA requires public notice and comment periods during EIS reviews,[195] to ensure public participation when the review is only in a CE or EA review, the NHPA should mandate a public notice and comment period. Both NEPA and the NHPA should require longer notice periods, more opportunities for hearings and comments, and more accessible and explanatory documents for the public to understand the action. The process should also include the public as soon as possible—even before notice—so that the agencies can understand the public’s stances prior to pitching actions and alternatives. Additionally, both statutes need to provide a private cause of action so that the public has a means of holding the agencies accountable for their actions.

Create Direct Communication Between Federal, State, and Tribal Offices and Mandate That They Consult With Each Other

One of the largest issues the intersection of the EIS and Section 106 analyses face is the failure to properly communicate between agencies and sovereigns. The Handbook acknowledged the difficulties agencies have in coordinating between different offices, agencies, and sovereigns, when it stated, “[c]onsider any agency-specific policies or practices that might complicate the process, such as delegation to local governments or applicants to act in the Federal agency’s stead.”[196] The federal agencies should implement shared sovereignty principles through policy guidelines or regulations that encourage effective communication and cooperation between agencies.[197] If the federal agencies fail to meet these goals, Congress should amend the statutes to require for this coordination and communication between agencies. Thus, to have a successful and protective analysis of cultural and historic property, NEPA environmental reviews and NHPA Section 106 analyses need to be amended to incorporate the changes outlined above.

NEPA and the NHPA are considered the magnum opuses of their respective fields,[198] but at their nexus, NEPA’s interaction with the NHPA’s Section 106 analysis fails to provide comprehensive protections to the environment, cultural resources, and historic properties.[199] The Trump Administration promulgated new CEQ regulations that amended longstanding NEPA practices, which further weakened the nexus of the two statutes’ analyses.[200] These new regulations will likely be revoked by the Biden Administration,[201] but they have highlighted the longstanding weaknesses in the nexus of the two statutes and have highlighted the need to analyze their intersection with more scrutiny. The Biden Administration should not simply reinstate the old CEQ regulations but should encourage the CEQ to release new regulations enhancing NEPA, and a new Handbook in coordination with the ACHP. Not only should the CEQ and ACHP promulgate new regulations, Congress should amend NEPA and the NHPA to better accommodate public participation, tribal consultation and decision-making power, and expand the NHPA Section 106 and NEPA EIS analyses to better coordinate and streamline the processes. To do so, Congress will need to amend NEPA to mandate tribal consultation, amend the NHPA to mandate public comment periods, and statutorily outline coordination efforts between federal, state, tribal, and local entities. The Biden Administration’s CEQ and ACHP must also prepare a new Handbook that is promulgated and enforced as a regulation under both agencies. The Handbook should require specified coordination timing, enforce detailed tribal consultation processes, outline a schedule for meaningful public comment and engagement periods allowing involvement in the historic property identification process, and create a structure in which to communicate and collaborate with cooperating agencies and federal, state, tribal, and local entities.

We have been relying on weak statutes at the intersection of environmental protection and historic preservation for far too long. The failures of the separate statutes are laid bare in their nexus, which highlights the need for change. These alterations and considerations will provide a more robust process that can successfully protect natural and cultural resources alike while combating environmental injustices through the empowerment of tribes over their land and a more inclusive public participation process.

- *Johnsie Wilkinson is a J.D. Candidate at Colorado Law. ↑

- Kurt Repanshek, Groups File Lawsuit to Stop Ambler Road Through Gates of the Arctic, National Parks Traveler, (Aug. 4, 2020), https://www.nationalparkstraveler.org/2020/08/groups-file-lawsuit-stop-ambler-road-through-gates-arctic. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Yereth Rosen, Tribal Governments Sue to Overturn Approval of Mining Road Proposed for Arctic Alaska, Arctic Today (Oct. 9, 2020),

https://www.arctictoday.com/tribal-governments-sue-to-overturn-approval-of-mining-road-proposed-for-arctic-alaska/. ↑

- Complaint at 55, 85–86, Alatna Village Council v. Padgett, No. 3:20-CV-00253 (D. Alaska Oct. 7, 2020). ↑

- NEPA Challenge Case Amount, Westlaw, https://1.next.westlaw.com (search for “NEPA”). ↑

- THE NHPA Challenge Case Amount, Westlaw, https://1.next.westlaw.com (search for “THE NHPA”). ↑

- Matthew J. Rowe, Judson B. Finley & Elizabeth Baldwin, Accountability or Merely “Good Words”? An Analysis of Tribal Consultation Under the National Environmental Policy Act and the National Historic Preservation Act, 8 Ariz. J. Env’t. L. & Pol’y 1, 1–2 (2018). ↑

- Jamie Auslander & Parker Moore, Natural Resources and Project Development: NEPA in Outlook for Environmental Issues in the Biden Administration, Beveridge & Diamond, (Jan. 27, 2021), https://www.bdlaw.com/publications/outlook-for-environmental-issues-in-the-biden-administration/; Akerman LLP, 2020 Election Impact: The Potential Effect of a Biden Administration on Environmental Policy–Change in Direction, Lexology (Nov. 10, 2020), https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=b4bbf5d4-1655-4c0d-b902-c479ab0ab708; Ellen Gilmer, Biden Officials Rethinking Trump Environmental Review Rule, Bloomberg News (Mar. 17, 2021), https://news.bloomberglaw.com/environment-and-energy/biden-officials-rethinking-trump-environmental-review-rule (In wake of the ongoing lawsuits, the courts will likely remand the rules to the CEQ because the “CEQ has identified numerous concerns with the 2020 Rule, many of which have been raised by Plaintiffs in this case, and has already begun reconsidering the Rule.”) (quoting Justice Department lawyers). ↑

- Coral Davenport, Biden Picks Deb Haaland to Lead Interior Department, N.Y. Times (Dec. 17, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/17/climate/deb-haaland-interior-department-native-american.html; Vanessa Friedman, Deb Haaland Makes History, and Dresses for It, N.Y. Times, (Mar. 19, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/19/style/deb-haaland-history-native-dress.html. ↑

- Council of Env’t Quality, Exec. Off. of the President, A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA: Having Your Voice Heard 2 (2007) [hereinafter A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA]; Robertson v. Methow Valley Citizens Council, 490 U.S. 332, 358–59 (1989). ↑

- Dean B. Suagee, THE NHPA § 106 Consultation: A Primer for Tribal Advocates, 65 Fed. Law. 40, 44 (2018); see also Rowe et al., supra note 8, at 2–3. ↑

- U.S. Dep’t of Interior, Bureau of Land Mgmt., Ambler Road: Environmental Impact Statement (2020). ↑

- Robertson, 490 U.S. at 348–51; A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA, supra note 11, at 2; Nat’l Park Serv., National Historic Preservation Act, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/historicpreservation/national-historic-preservation-act.htm (last visited Dec. 2, 2020). ↑

- National Environmental Policy Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 4321–4370 (1970). ↑

- NEPA, CEQ, Nepa.gov, https://ceq.doe.gov/ (last visited Apr. 13, 2021). ↑

- EPA, What is the National Environmental Policy Act?, https://www.epa.gov/nepa/what-national-environmental-policy-act (last visited Apr. 13, 2021). ↑

- 42 U.S.C. § 4332. ↑

- Id. § 4332(C). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Vt. Yankee Nuclear Power Corp. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 435 U.S. 519, 523 (1978). ↑

- A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA, supra note 11, at 10. ↑

- Id. at 11. ↑

- Id. at 12. ↑

- Id. at 10. ↑

- Id. at 19. ↑

- Id. at 8. ↑

- See Metro. Edison Co. v. People Against Nuclear Energy, 460 U.S. 766 (1983). ↑

- Exec. Order No. 12,898, 59 Fed. Reg. 7629 (Feb. 16, 1994). ↑

- See Kleppe v. Sierra Club, 427 U.S. 390 (1976). ↑

- 40 C.F.R. § 1501.2 (2012). ↑

- Update to the Regulations Implementing the Procedural Provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act, 85 Fed. Reg. 43304, 43310–12 (July 16, 2020). ↑

- Council on Env’t Quality, Final Rule Redline of 1978 CEQ Regulations (2020), https://ceq.doe.gov/docs/laws-regulations/ceq-final-rule-redline-changes-2020-07-16.pdf. ↑

- See Robertson v. Methow Valley Citizens Council, 490 U.S. 332 (1989); Strycker’s Bay Neighborhood Council, Inc. v. Karlen, 444 U.S. 223 (1980); Vt. Yankee Nuclear Power Corp. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 435 U.S. 519 (1978). ↑

- Final Rule Redline of 1978 CEQ Regulations, supra note 34, at 6, 10–11, 61, 63. ↑

- Council on Env’t Quality, Exec. Off. of the President & Advisory Council on Historic Pres., NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook for Integrating NEPA and Section 106, 4 (2013) [hereinafter NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook]. ↑

- National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, 54 U.S.C. § 306108; 16 U.S.C. § 470f (2012) (repealed 2014). ↑

- Nat’l Park Serv., National Historic Preservation Act 1, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/historicpreservation/national-historic-preservation-act.htm (last modified Dec. 2, 2019). ↑

- 16 U.S.C. § 470(b)(4). ↑

- Id. § 470f. ↑

- 36 C.F.R. § 60.4 (2020). ↑

- 16 U.S.C. § 470f. ↑

- Id. ↑

- 36 C.F.R. § 800. ↑

- Id. § 800.2(b). ↑

- Id. § 800.1(c) ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. § 800.2(a)(3). ↑

- Id. § 800.2. ↑

- Id. §§ 800.3–8. ↑

- Id. § 800.2(b). ↑

- Id. § 800.2(b)(2)(C). ↑

- Id. § 800.2(d). ↑

- Exec. Order No. 11,593, 36 Fed. Reg. 8921, 8921 (May 15, 1971). ↑

- NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37, at 4. ↑

- Exec. Order No. 13,007, 3 C.F.R. 196, 196–97 (1996). ↑

- Id. ↑

- NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37, at 11–12. ↑

- Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, Section 106 Review Process Flowchart 1, https://www.achp.gov/digital-library-section-106-landing/section-106-review-process-flowchart (last visited Apr. 13, 2021). ↑

- 36 C.F.R. § 800.8. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- See generally NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37. ↑

- Id. at 4. ↑

- Id. at 6. ↑

- Id. at 12. ↑

- Id. at 4. ↑

- Id. at 18–33. ↑

- Id. at 13. ↑

- Id. at 14. ↑

- 36 C.F.R. § 800.1(a). ↑

- NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37, at 15. ↑

- Id. at 15–16. ↑

- Exec. Order No. 13,175, 3 C.F.R. 304, 305 (2000). ↑

- Id. at 306. ↑

- In 2017, 26.8% of American Indian and Alaska Natives were estimated to be living in poverty. Nat’l Cong. Of Am. Indians, Indian Country Demographics, https://www.ncai.org/about-tribes/demographics (last updated June 1, 2020). ↑

- Exec. Order No. 12,898, 3 C.F.R. 276, 276 (1994). ↑

- NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37, at 16. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 17. ↑

- Id. ↑

- 36 C.F.R. § 800.8(b). ↑

- NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37, at 19. ↑

- A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA, supra note 11, at 10. ↑

- Id. at 41. ↑

- NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37 at 19. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 22. ↑

- A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA, supra note 11, at 11. ↑

- NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37, at 22. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 23. ↑

- Id. at 23–24. ↑

- Id. at 25. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 26. ↑

- A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA, supra note 11, at 16. ↑

- NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37, at 27 (footnote omitted). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 28. ↑

- Id. at 29. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 30. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 31–33. ↑

- Nat’l Capital Planning Comm’n, Environmental and Historic Preservation Compliance 6 (2019), https://www.ncpc.gov/docs/publications/NEPA-THE NHPA_Resource_Guide_2019.pdf. ↑

- See Seema Kakade et al., Navigating NEPA 50 Years Later: The Future of NEPA, 50 Env’t L. Reporter 10273 (2020). ↑

- National Association of Environmental Professionals, 2018 Annual NEPA Report of the NEPA Practices 7 (2019). ↑

- Helen Leanne Seassio, Legislative and Executive Efforts to Modernize NEPA and Create Efficiencies in Environmental Review, 45 Tex. Env’t L. J. 317, 317 (2015). ↑

- Vt. Yankee Nuclear Power Corp. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 435 U.S. 519, 542–58 (1978). ↑

- Mark A. Chertok, “Little NEPAs” and Their Environmental Impact Assessment Procedures, ALI-ABA Course of Study Environmental Litigation 921, 924 (2011). ↑

- Minn. Stat. § 116D.04, subdiv. 6 (emphasis added). ↑

- Id. ↑

- 301 Mass. Code Regs. 11.01(1)(a) (2013) ↑

- Ultramar, Inc. v. S. Coast Air Quality Mgmt. Dist., 21 Cal. Rptr. 2d 608, 616 (Cal Ct. App. 1993). ↑

- 301 Mass. Code Regs. 11.04. ↑

- Vt. Yankee Nuclear Power Corp. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 435 U.S. 519, 558 (1978). ↑

- Strycker’s Bay Neighborhood Council, Inc. v. Karlen, 444 U.S. 223, 227 (1980). ↑

- Robertson v. Methow Valley Citizens Council, 490 U.S. 332, 353 (1989). ↑

- Kelsey Kahn, NEPA’s Fatal Flaw, an Impediment to Collaboration, Univ. of Utah: EDR Blog (Sept. 28, 2015), https://law.utah.edu/nepas-fatal-flaw-an-impediment-to-collaboration/. ↑

- A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA, supra note 11, at 10–13. ↑

- See Kakade, et al., supra note 113. ↑

- Rowe et al., supra note 8, at 43. ↑

- NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37, at 14, 28. ↑

- Rowe et al., supra note 8, at 3. ↑

- Council on Env’t Quality, CEQ NEPA Regulations, https://ceq.doe.gov/laws-regulations/regulations.html (last visited Apr. 12, 2021). ↑

- Exec. Order No. 12,898, 59 Fed. Reg. 7629 (Feb. 16, 1994). ↑

- Rowe et al., supra note 8, at 3. ↑

- NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37, at 7, 10. ↑

- Michael C. Blumm & Andrea Lang, Shared Sovereignty: The Role of Expert Agencies in Environmental Law, 42 Ecology L. Q. 609, 611 (2015). ↑

- 40 C.F.R. § 37 (2019). ↑

- 40 C.F.R. § 1500 (2020). ↑

- Id. §§ 1501.4, 1502, 1503, 1504, 1508.7, 1508.27. ↑

- Id. § 1503.3. ↑

- Extension of Public Comment Periods Amid COVID-19 Pandemic, Amnesty Int’l (Mar. 20, 2020), https://www.amnestyusa.org/our-work/government-relations/advocacy/extension-of-public-comments-amid-covid-19-pandemic/. ↑

- A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA, supra note 11, at 4. ↑

- Complaint at 48, Cal. et al. v. Council on Env’t Quality, No. 3:20-cv-06057 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 28, 2020). ↑

- Id. at 4. ↑

- Complaint at 4, Alaska Cmty. Action on Toxins v. Council on Env’t Quality, No. 3:20-cv-05199 (N.D. Cal. July 29, 2020). ↑

- Complaint at 2, Wild Va. v. Council on Env’t Quality, No. 3:20-cv-00045 (W.D. Va. July 29, 2020). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Akerman LLP, supra note 9; Gilmer, supra note 9. ↑

- See Jess R. Phelps, The National Historic Preservation Act at Fifty: Surveying The Forest Service Experience, 47 Env’t. L. 471 (2017). ↑

- Melissa A. McGill, Old Stuff is Good Stuff: Federal Agency Responsibilities Under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, 7 Admin. L. J. Am. U. 697, 709 (1993). ↑

- Adina W. Kanefield, Advisory Council on Hist. Pres., Federal Historic Preservation Case Law 1966-1996, at 61 (1996). ↑

- Phelps, supra note 149, at 484. ↑

- Amanda M. Marincic, The National Historic Preservation Act: An Inadequate Attempt to Protect the Cultural and Religious Sites of Native Nations, 103 Iowa L. Rev. 1777, 1809 (2018). ↑

- Kanefield, supra note 151, at 33. ↑

- Leslie E. Barras, Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act: Back to Basics 8 (2010). ↑

- 16 U.S.C. § 470. ↑

- Marincic, supra note 153, at 1783. ↑

- Brenda Barrett et al., Comments on the Ambler Road Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS), The Coal. to Protect Am.’s Nat’l. Parks (Oct. 29, 2019), https://protectnps.org/2019/10/30/coalition-comments-on-the-ambler-road-draft-environmental-impact-statement/. ↑

- 36 C.F.R. § 800.5(a). ↑

- Patricia L. Parker & Thomas F. King, Nat’l Bull. Reg., Guidelines For Evaluating and Documenting Traditional Cultural Properties 1 (1990). ↑

- See infra § I.B. ↑

- Connie Rogers, Native American Consultation in Resource Development on Federal Lands, 31 Colo. Law. 113, 114–19 (2002). ↑

- Peter J. Gardner, The First Amendment’s Unfulfilled Promise in Protecting Native American Sacred Sites: Is the National Historic Preservation Act a Better Alternative?, 47 S.D. L. Rev. 68, 81 (2002). ↑

- NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37, at 28. ↑

- Ctr. For Env’t Excellence, Am. Assoc. of State Highway and Transp. Officials, AASHTO Practitioner’s Handbook: Consulting Under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act 1 (2016). ↑

- Charles Rennick, The National Historic Preservation Act: San Carlos Apache Tribe v. United States and the Administrative Roadblock to Preserving Native American Culture, 41 New Eng. L. Rev. 67, 95 (2006); Daniel E. Walker, A Statute Without Teeth: Is a Private Right of Action in the National Historic Preservation Act Necessary For Meaningful Cultural Resource Protection?, 44 Vt. L. Rev. 379, 394 (2019); Marincic, supra note 153, at 1793. ↑

- Bradford C. Mank, Is There a Private Cause of Action Under EPA’s Title VI Regulations?: The Need to Empower Environmental Justice Plaintiffs, 24 Colum. J. Env’t. L. 1, 33 (1999). ↑

- 42 U.S.C. § 7604; Joshua B. Frank et al., Clean Air Act Citizen Suits: Defense and Litigation Strategies, Strafford (July 18, 2017), https://foleyhoag.com/-/media/files/foley%20hoag/speaking%20engagements/2017/jaffe_clean_air_act%20suits_webinar_july2017.ashx?la=en. ↑

- James R. May, Now More Than Ever: Trends in Environmental Citizen Suits at 30, 10 Widener L. Rev. 1, 6 (2003); see also Neil A.F. Popovi, The Right to Participate in Decisions that Affect the Environment, 10 Pace Env’t L. Rev. 683, 701 (1993). ↑

- Terence J. Centner, Challenging NPDES Permits Granted Without Public Participation, 38 B.C. Env’t Aff. L. Rev. 1, 14 (2011). ↑

- Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. § 555 (2006). ↑

- Michael I. Jeffrey, Intervenor Funding as the Key to Effective Citizen Participation in Environmental Decision-Making: Putting the People Back into the Picture, 19 Ariz. J. Int’l & Comp. L. 643, 654 (2002); Stephen Fotis, Private Enforcement of the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act, 35 Am. U. L. Rev. 127, 138–143 (1985); Walker, supra note 166, at 395–96. ↑

- Marincic, supra note 153, at 1788. ↑

- H. Barry Holt, Archeological Preservation on Indian Lands: Conflicts and Dilemmas in Applying the National Historic Preservation Act, 15 Env’t L. 413, 438 (1985). ↑

- S. Rheagan Alexander, Tribal Consultation for Large-Scale Projects: The National Historic Preservation Act and Regulatory Review, 32 Pace L. Rev. 895, 895 (2012). ↑

- Marincic, supra note 153, at 1777. ↑

- Holt, supra note 174, at 417. ↑

- National Historic Preservation Act Amendments of 1992, Pub. L. No. 102-575, 106 Stat. 4753, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-106/pdf/STATUTE-106-Pg4600.pdf; Paul R. Lusignan, Traditional Cultural Places and the National Register, 26 George Wright Forum 37, 37–39 (2009). ↑

- Holt, supra note 174, at 438. ↑

- See generally William Claiborne, U.S., Indians Fight Over Role in Protecting Sacred Sites, Washington Post (Nov. 28, 1998) https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1998/11/28/us-indians-fight-over-role-in-protecting-sacred-sites/b332df64-a96d-4ddc-8f64-cf62262ced37/. See also San Carlos Apache Tribe v. United States, 417 F.3d 1091 (9th Cir. 2005); Havasupai Tribe v. Provencio, 906 F.3d 1155 (9th Cir. 2018); Pit River Tribe v. U.S. Forest Serv., 469 F.3d 768 (9th Cir. 2006); Quechan Tribe of Fort Yuma Indian Rsrv. v. U.S. Dep’t of Interior, 755 F. Supp. 2d 1104 (S.D. Cal. 2010); Yankton Sioux Tribe v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 194 F. Supp. 2d 977 (D.S.D. 2002). ↑

- NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37, at 33. ↑

- Hari M. Osofsky, Rethinking the Geography of Local Climate Action: Multilevel Network Participation in Metropolitan Regions, 2015 Utah L. Rev. 173, 173 (2015). ↑

- Repanshek, supra note 1. ↑

- Id. ↑

- BLM, Project Overview: Ambler Mining District Industrial Access Road Project (2016), https://eplanning.blm.gov/public_projects/nepa/57323/131036/160083/Ambler_Road_EIS_Section_106_Presentation.pdf. ↑

- Repanshek, supra note 1. ↑

- Id. ↑

- See infra § II. ↑

- See NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37. ↑

- Id. at 33. ↑

- Rowe et al., supra note 8, at 5. ↑

- NEPA and THE NHPA: A Handbook, supra note 37, at 33. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 14. ↑

- Id. at 33. ↑

- Blumm & Lang, supra note 136, at 611. ↑

- Robertson v. Methow Valley Citizens Council, 490 U.S. 332, 350–59 (1989); A Citizen’s Guide to NEPA: A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA, supra note 11, at 11; Nat’l Park Serv., supra note 14. ↑

- Rowe et al., supra note 8, at 5. ↑

- See Council on Env’t Quality, supra note 34. ↑

- Akerman LLP, supra note 9; Gilmer supra note 9. ↑