The world is becoming increasingly interconnected, and our understanding of climate change and pollution now expands beyond the borders of individual countries. Even when the United States monitors and regulates its own contribution to emissions and pollution, these pressing issues are impossible to control through domestic regulation alone. Many goods consumed by Americans are produced overseas. Federal agencies have the ability to regulate the kinds of products that come into the country, yet these agencies have little control over the methods by which those products were produced—even if they were manufactured in a far more environmentally destructive manner than the laws of the United States permit.

Major discrepancies still exist between pollution outputs created in developed countries and outputs from developing countries. Many developing countries have environmental laws and regulations in place, but often do not have the resources to enforce them.[2] As a result, there is an inevitable gap between the process quality of products and materials that are produced in developing countries compared to those produced in countries with structured environmental agencies like the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”). This Note will focus on ways the U.S. government can close loopholes in environmental regulation and policy to ensure companies that manufacture products overseas do so in an environmentally conscious manner.

First, simply calculating emissions within the borders of the United States does not accurately reflect the nation’s carbon footprint because it does not account for the manufacture of goods produced overseas for U.S. companies and consumers. Second, various legal barriers, both domestic and international, limit the ability of the United States to monitor and regulate the manufacturing process abroad. This Note will analyze China’s manufacturing relationship with the U.S. in the 2000s, and how China’s lack of environmental regulations and pollution data continues to affect the United States. Finally, there are several potential solutions through which the United States can monitor and regulate imported products in ways that will not overstep its authority.

I. U.S. Industrial Emissions have Decreased, but Overseas Manufacturing is Not Accounted for

The 1970s marked a turning point for American manufacturing and environmental regulation.[3] Increased production and large-scale consumption in the twentieth century caused a sharp rise in pollution in the United States.[4] Air pollutants like carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen oxides reached a peak in 1970.[5] In heavily industrialized areas, catastrophic events such as the infamous Cuyahoga River fire in 1969 were visual reminders of how polluted rivers had become in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.[6] In response to numerous environmental disasters and mounting political pressure, Congress enacted several landmark statutes in the 1970s, including the Clean Air Act (“CAA”) and Clean Water Act (“CWA”), that created the groundwork for environmental regulation.[7] Additionally, Congress funded the EPA in 1970 as the regulatory body charged with executing environmental laws and regulations.[8]

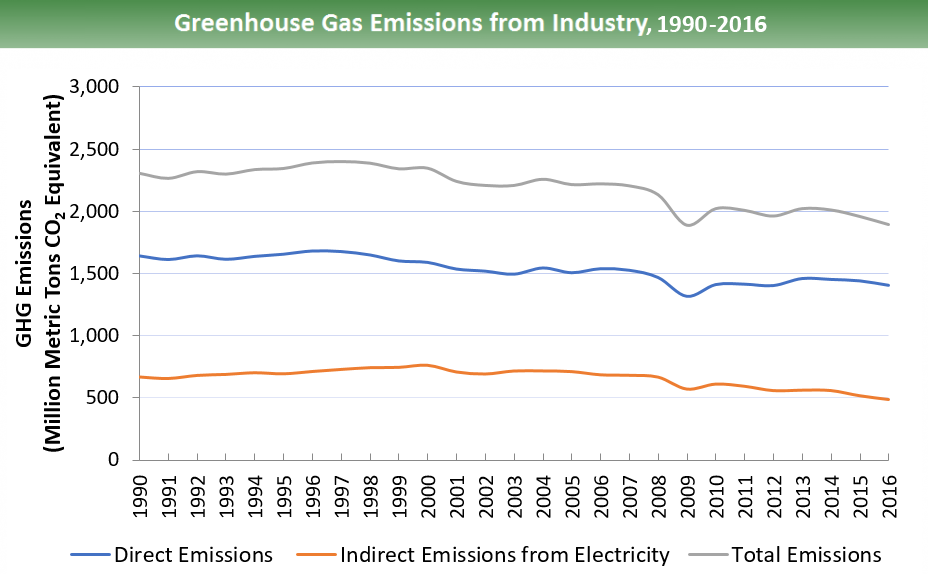

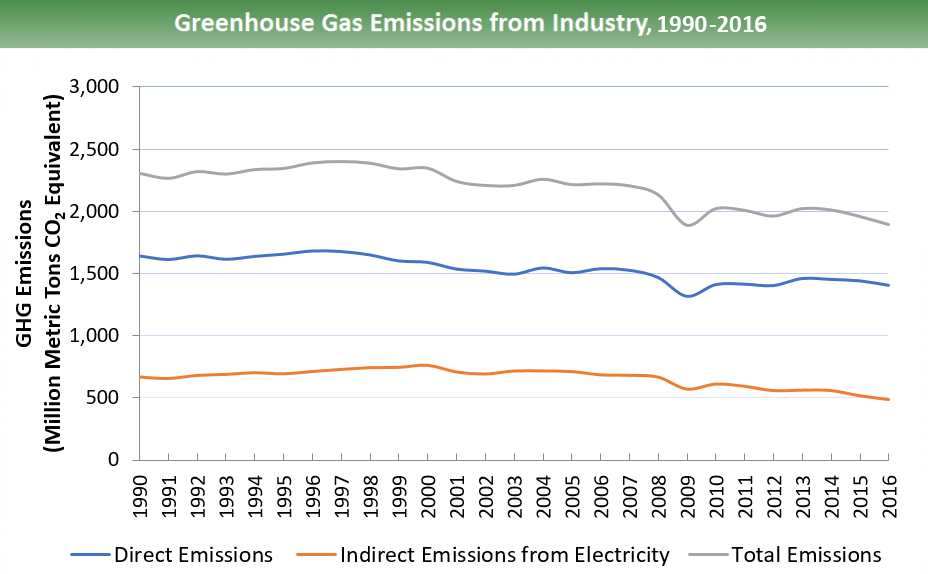

Environmental regulation affected every facet of American life, including the manufacturing industry. Increased regulation and political scrutiny forced U.S. manufacturers and producers to reduce and mitigate pollution.[9] Due to these regulations, air and water quality within the U.S. improved significantly.[10] Emissions continued to decline into the twenty-first century.[11] But as the U.S. government began to implement and enforce environmental regulation, environmental and labor costs increased as well.[12] Although manufacturing continued to play a major role in the U.S. economy—indeed, the manufacturing sector’s value actually increased—employment in the manufacturing sector fell.[13]

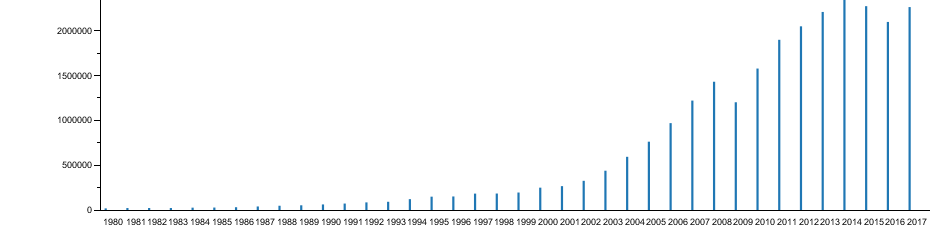

Figure 1: The EPA has reported a steady decline in industry-related greenhouse gas emissions in the United States over the past several decades.[14]

At the same time, the country also saw a rise in the importation of goods and parts from developing countries.[15] Companies based in countries like the United States moved factories to developing countries such as China and Mexico.[16] These countries provided companies with factories, cheaper labor, and favorable laws.[17] These moves did not go unnoticed, and companies were accused of “offshoring” their manufacturing process, skirting around local laws that regulated labor and pollution.[18] Emissions rose in these developing countries, and it seemed as if the United States simply displaced the pollution its environmental laws attempted to eliminate.[19] There is evidence showing that higher environmental regulation and the existence of regulatory schemes like pollution abatement costs correlate with an industry shift to developing countries.[20] Some economists refer to the industrial shift towards developing countries as the “Pollution Haven Hypothesis.”[21] This economic hypothesis predicts that companies located in countries with stricter environmental regulations will move production to countries with looser environmental regulations, so long as there is not a barrier to trade between countries.[22] However, a plethora of other factors show that there was not a simple, direct relationship between the decline of pollution in a country like the United States and the increase of pollution in other countries.[23]

Growing consumer markets in developing countries, for example, meant that companies moved their factories and production lines to be closer to their new customers.[24] Changes in technology also contributed to the decrease of pollution emitted through industrial manufacturing, in no small part due to the regulations that significantly increased the costs associated with pollution.[25] The theory suggesting that countries with more stringent environmental regulations develop cleaner technology is called the “Porter Hypothesis.”[26] This economic theory suggests that innovative technologies are driven by regulation, as companies have the incentive to avoid penalties or abatement costs if their facilities do not meet a country’s environmental standards.[27] Once cleaner technology has been implemented, the theory states that governments that value product quality will favor the environmentally conscious product, and exports will increase.[28] Yet, even exporting countries with stringent environmental regulations, like the United States, still import a significant amount of goods from countries with lower environmental standards.

Manufacturing does not account for all the pollution and emissions produced by the United States. Most pollution comes from consumption, rather than production.[29] Driving cars, running trains and buses, and lighting and heating homes with fossil fuels produce a significant amount of pollution.[30] In 2016, twenty-eight percent of greenhouse gas emissions produced by the United States were from the transportation sector, and another twenty-eight percent were from electricity production.[31] Twenty-two percent of U.S. emissions were produced by the industrial sector.[32] Changes in pollution levels and the effects of environmental laws and changing technology are more apparent in the former two sectors because most of the emissions and waste from these sectors are created within the United States. However, the U.S. industrial sector does not account for all of the goods that were actually produced for the consumption of American residents.[33] The pollution produced to create, ship, and consume a product is harder to track in an increasingly global market.

II. Current Laws and Regulations Provide Little Environmental Oversight on Imported Goods

The EPA primarily executes the laws and regulations that govern pollution in the United States. These laws govern pollution production within the U.S., leaving a gap in regulation of production lines for American companies—the production of foreign imports. Although domestic and international laws can encourage American consumers and producers to import ethically sourced goods and products, these measures are limited and ineffective.

A. U.S. Environmental Laws Grant Agencies Limited Authority over Imported Goods

Congress has the ability to regulate international trade and imports, but its authority rarely extends to monitor the environmental impact that production of certain goods has on the environment. While Congress has given the Fish and Wildlife Service the ability to monitor the importation of non-native species and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association the authority to regulate imported seafood to ensure sustainable harvesting, the EPA has little to do with products that are produced outside of U.S. jurisdiction.[34]

The EPA has significant authority over activity within the United States. Congress authorizes the EPA to implement and enforce regulations that reduce emissions and waste through the CWA, the CAA, and the Toxic Substances Act.[35] Through these statutes, the EPA sets regulations that govern how much of each pollutant is reasonable, how much individual polluters can emit, and tools to enforce compliance.[36] The CAA, for example, gives the EPA authority to inspect facilities and impose civil and criminal penalties.[37] The CAA also allows the public to bring citizen suits, permitting individuals to directly sue a violator if the EPA does not take action.[38] The EPA also has the authority to mandate reporting.[39] The ability of the government to require companies to give information has significantly increased the agency’s understanding of emission and pollution, and allows for substantive measures to be taken based on that data. Like its other provisions, however, the EPA’s authority to gather information is limited to the United States.

The Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, for example, requires production facilities from petroleum refineries and iron and steel production to report emissions.[40] All facilities in the United States and on the continental shelf must report various emissions identified by the CAA, as well as carbon dioxide emissions, depending on the type of pollution typically emitted by the particular industry in which each facility operates.[41] On the other hand, the reporting requirement only extends to importers of “Coal based liquid fuels (subpart LL), Petroleum products (subpart MM), Industrial gases (subpart OO), Carbon dioxide (subpart PP), and Fluorinated GHGs [greenhouse gases] contained in pre-charged equipment or closed-cell foams (subpart QQ).”[42] All of these imports are fuels that will physically burn and release emissions in the United States. The regulation is not concerned with the emissions that foreign petroleum refineries will emit while producing such fuels. The government is concerned with pollution produced within the United States, but not pollution emitted anywhere else.[43]

The problem with this system, particularly regarding the CAA, is that pollution is ubiquitous. Regional air quality may vary for concentrated pollutants like particulate matter, but air pollutants can affect the globe regardless of where they are emitted.[44] The system ignores air pollution emitted by China while manufacturing goods destined for U.S. consumption. Expansion of what the EPA could regulate, or monitor at the very least, would be needed to assess the true environmental impact of the United States. However, a line of international case law and a lack of reliable information limits the ability of the United States to regulate the environmental quality of imports.

B. The World Trade Organization Limits any Country’s Ability to Regulate Foreign-Produced Goods

The United States has the ability to regulate what comes in and out of the country.[45] However, certain limitations apply when countries deal with foreign trade. One of these limitations is the anti-discriminatory provisions laid out by the World Trade Organization (“WTO”) for member states.[46] The WTO is an intergovernmental trading organization that oversees global trade agreements.[47] In addition to facilitating negotiation, the WTO also provides arbitration and acts as a neutral body to bring trade disputes between nations.[48] The WTO’s governing articles, known as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (“GATT”), prohibit countries from granting other countries special trading privileges.[49] This extends to “imported goods [that] will be accorded the same treatment as goods of local origin with respect to matters under government control, such as taxation and regulation.”[50] This provision limits a country’s ability to put restrictions specifically on the process in which certain goods are produced. One of the most important roles of the WTO is to prevent trade discrimination between countries.[51] This provision creates a difficult barrier for environmental import restrictions because discrimination can come in the form of bans on unethically produced or pollution-heavy materials. Traditionally, bans on the importation of materials harvested in an environmentally destructive manner have put underdeveloped countries at a natural disadvantage because they do not have the resources to develop cleaner methods of production.

Like in all international organizations, membership in the WTO is voluntary.[52] Currently, 164 countries hold membership.[53] The United States is a member of the WTO.[54] Member states that have agreements with each other can bring action against states whom they believe are acting illegally or against international agreements.[55] Unlike most international bodies, the WTO has enforcement mechanisms in place that usually come in the form of retaliatory trade embargoes.[56] The United States defers to the WTO as the “foundation of the global trading system.”[57] The federal government has a codified system for implementing dispute settlements in order to comply with the WTO’s decisions.[58] The WTO wields political and economic power, and the possibility of member countries enacting an embargo on a country that refuses to comply with a decision threatens a high price to pay.

Although the WTO concerns itself with protecting free trade, it does acknowledge that a country’s environmental concerns can take precedence in practices that may otherwise be considered discriminatory. GATT’s article XX provides “general exceptions” to the agreement, including measures “necessary to protect human, animal, or plant life and health,” so long as those measures are “not applied in a manner which would constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination between countries where the same conditions prevail.”[59] The following cases adjudicated by the WTO strove to clarify the provision.

The attempts by the United States to implement environmentally conscious importation restrictions have received mixed treatment from the WTO. Take, for example, the case of U.S.-Gasoline. In U.S.-Gasoline and a domestic companion case, George E. Warren Corp. v. E.P.A., the WTO first demonstrated the willingness to limit the United States and its ability to control imports on foreign-based products.[60] In accordance with the 1990 CAA amendments, the EPA promulgated an antidumping rule requiring foreign gasoline refiners to either import fuel that produced emissions below the set statutory baseline or to petition the EPA for an individual baseline that allowed the refiner to import gasoline with higher emissions.[61] The previous rule had, in practice, forced foreign refiners to comply with the statutory baseline while domestic importers could establish individual baselines.[62] The WTO determined that the rule’s preference for domestic refiners was discriminatory and violated GATT.[63] The EPA’s initial reasons behind subjecting foreign refiners to different standards lay in the fact that they were not “subject to the full panoply of EPA’s regulatory jurisdiction” beforehand; the agency could only compare the fuel quality to American baseline standards.[64]

The EPA’s concern with its inability to regulate the production and process of foreign imports is telling. Its concern stemmed from the fact that the EPA could not regulate how “clean” gasoline intended for domestic consumption was, nor the associated release of pollution into the atmosphere.[65] The emissions created by refining the gasoline itself were not at issue here. Even so, the EPA revised the rule when the WTO handed down its opinion.

The next environmental case, Shrimp-Turtle, took a different turn.[66] The United States passed a law in 1989 prohibiting the importation of shrimp caught with nets that did not have Turtle Excluder Devices (“TEDs”), mechanisms that reduced the chance of certain endangered turtle species being harmed by shrimp nets.[67] India, Malaysia, Pakistan, and Thailand appealed the law to the WTO, claiming that it prevented them from trading with the United States.[68] These countries did not have the resources to implement TEDs, and the law prevented them from trading regardless of whether turtles were actually harmed.[69] The appellate panel agreed with the complaining states.[70] The protection of sea turtles was a legitimate exception to trade as provided by GATT under article XX, and the panel ruled that countries had the right to protect the environment through trade.[71] It still concluded, however, that the law was discriminatory between WTO members and therefore did not meet the requirements for the exception to apply.[72] The primary reason for this was that the United States provided aid to countries in the Caribbean to install TEDs, but offered no such aid to eastern countries like the complainants.[73]

As Shrimp-Turtle highlighted, legitimate exceptions to trade discrimination can apply. In addition to employing restrictions, such as a ban on goods produced with deceptive practices and prison labor or a law regarding a material that is “necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health,”[74] a country that aims to conserve an “exhaustible natural resource” may use trade measures to control production or consumption within its jurisdiction.[75] The turtles at issue in Shrimp-Turtle migrated through U.S. waters, so there was a “sufficient nexus” between U.S. interests and the turtles themselves.[76] However, the regulation itself must not constitute “unjustifiable discrimination” and it also must legitimately target the identified problem.[77]

In a similar case, U.S.-Tuna, which originally began in 1991, Mexico asked the WTO to review a U.S. law that required countries exporting tuna to prove to U.S. authorities that the tuna had been caught using dolphin-friendly methods.[78] This measure, Mexico argued, had a detrimental impact on its tuna products, as Mexico’s domestic regulations did not meet U.S. standards.[79] If a given fish product did not meet the standards, the United States would ban all fish products from any country that caught or processed such product.[80] The WTO panel concluded that the United States could not apply U.S. regulations to Mexican production methods.[81] It could regulate the quality of the final product itself for health reasons, but the WTO raised concerns about countries that would attempt to impose their own laws and regulations on other nations.[82] The law in Shrimp-Turtle stemmed from the desire to protect five different species considered endangered in U.S. waters, and the foreign fishing practices that contributed to their decline.[83] In U.S.-Tuna, the WTO saw the U.S. government attempting to influence Mexican regulations regarding dolphins without reference to how they affected the United States and its “exhaustible resources.”[84]

The original 1991 report was never officially adopted, and Mexico and the United States continued to clash over environmental regulations, this time concerning tuna labelling requirements.[85] A new U.S. labelling regime required tuna products to prove that fishermen used safe measures, or that the specific catch of tuna had not resulted in the deaths of any dolphins.[86] Mexico brought the case to the WTO again in 2012, complaining that the new regime had a detrimental impact on its trade.[87] Mexico argued that the measures did not actually address the problem but were a technical barrier to trade (“TBT”) which the WTO excludes through the TBT Agreement.[88] The appellate body disagreed, analyzing the multiple steps the United States took to monitor and report tuna fishing and its impacts on dolphins, and concluded that these measures were rationally related to the conservation of exhaustible natural resources.[89] The panel rejected Mexico’s claims against the U.S. labelling requirement.[90]

The U.S.-Tuna appellate panel clarified that “one of the most important factors in the assessment of arbitrary or unjustified discrimination under [Article XX] is the question of whether the discrimination can be reconciled with, or is rationally related to, the policy objective” that has been justified under Article XX.[91] In order to implement environmental protections on imports, the importing country must show how that protection would benefit itself, rather than the origin country. The United States cannot ban a product from Mexico because it believes it will damage Mexico’s environmental quality; it must show how that product damages environmental quality in the United States. Even if it can show that there is a nexus between the product and U.S. jurisdiction, the United States must also show that the measures in place are there to actually meet its purported objective, and not simply there to hinder trade with Mexico. Because the labelling requirement was rationally related to the protection of individual dolphins, it survived the WTO’s scrutiny.[92]

C. The United States Lacks Reliable Information Regarding Pollution and Emissions that Originate Beyond its Borders, as its Trade Relationship with China Demonstrates

The U.S. trading relationship with China illustrates the limits on its ability to control how much it contributes to global pollution. In the past several decades, numerous corporations made the decision to move overseas or to contract with foreign manufacturers for parts. China was the posterchild for U.S. outsourcing in the 1990s and 2000s, and supplied products anywhere from textiles to steel.[93] In 2010, China surpassed the United States as the world’s largest manufacturer.[94] While China’s manufacturing industry is now one of the largest in the world, it is also one of the dirtiest.[95] Yale University’s Environmental Performance Index ranked China’s regulatory index as 120th in the world (the United States was ranked twenty-seventh).[96] The country scored particularly poorly on the air quality index score.[97] The large nation has taken steps in the past decade to try to curb its emissions in an attempt to improve living quality and labor concerns.[98] However, the United States’ reliance on China and the country’s lack of environmental regulations in the 1990s and 2000s serve as an example of the environmental impact American companies contributed to global pollution without regulation or oversight.

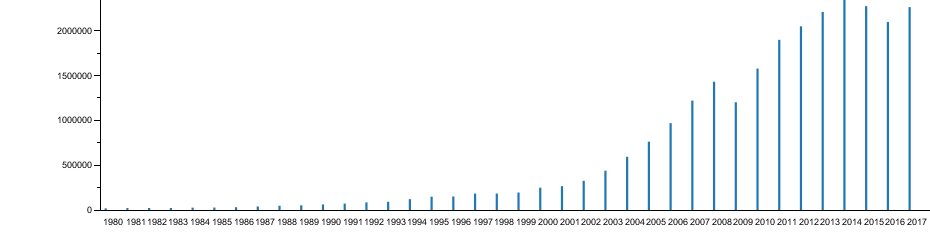

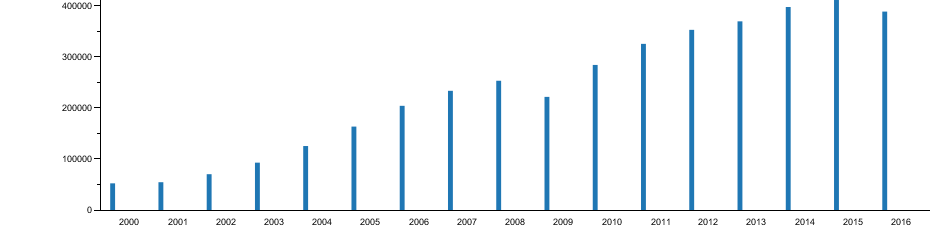

China’s industrialization in the latter half of the twentieth century has made it the hub of manufacturing for American firms.[99] By 2011, China accounted for 25.5 percent of the entire world’s carbon dioxide emission output.[100] At the same time, the U.S. trade deficit in China grew significantly.[101] The electronics industry had a deficit of fifty-five percent of gross industry output, thirty-eight percent of which were imports from China.[102] American corporations like Apple Inc. contract with or own factories in China to manufacture and assemble products.[103]

Figure 2: China’s Total World Exports (in $1,000,000) from 1980-2017.[104]

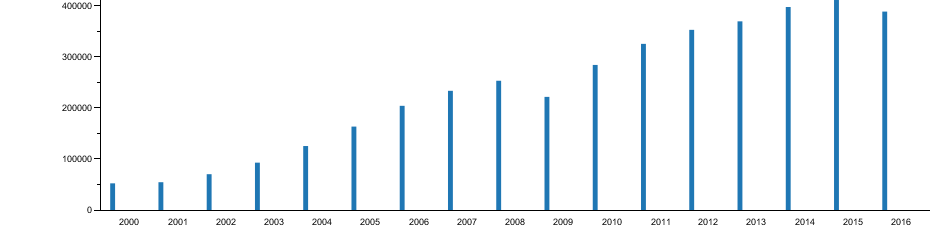

Figure 3: China’s Total Exports (in $1,000,000) to the United States from 2000-2016.[105]

Despite the country’s agreement to both the Kyoto Protocol and the United Nations Conference on Climate Change, China did little in practice to regulate pollution and emissions in the 2000s.[106] China’s version of the EPA has a much smaller budget and workforce than its American counterpart.[107] Unlike the American system, which delegates the authority to enforce environmental provisions through a federal system that applies to all states, China’s system is much more localized.[108] The result is an environmental scheme that is much harder to keep track of, and local authorities that prioritize economic development over environmental protection.[109] While this mindset can help attract foreign companies to Chinese provinces, creating economic opportunity, the sole focus on production has contributed to rapid environmental destruction.[110]

The United States can account for the pollution it creates via consumption through its own consumption and manufacturing facilities, but it is difficult to account for the pollution that affects the country. For example, air pollution is difficult to isolate by country because it can affect the entire globe.[111] The EPA has taken steps to track how local air pollution flows across borders.[112] At the height of China’s pollution output in the 2000s, studies suggested that particulate pollution over West Coast cities like Los Angeles originated from China.[113] Over the past decade, the Chinese government seemed to have recognized the severity of the pollution problem. The government has since modified environmental laws, such as a 2013 amendment to the Environmental Protection Law, which introduced, among other things, public interest lawsuits.[114] However, China’s recent aggressiveness towards pollution is a new phenomenon and does not yet address environmental concerns nearly to the extent that the United States and other countries do. In 2016, for example, Chinese air quality inspectors reported that a large number of corporations were falsifying emission data.[115]

The proposed Foxconn factory in the United States provides a recent example of the concern for Chinese-based facilities and their looser environmental regulatory standards. The company, which has contracted with Apple Inc. to manufacture its products for a long time, is set to open a new factory in Wisconsin.[116] Environmentalists raised concerns that a new factory will cause unexpected pollution issues, as Chinese regulations do not require companies to disclose all pollution threats.[117] The company managed to bypass some domestic environmental procedures through the Trump administration, and opponents were concerned that the plant would become the state’s leading source of pollution.[118] On the state level, Wisconsin passed a bill that designated the proposed site as an “Electronics and Information Technology Manufacturing Zone,” which exempted the company from state wetland and waterway permits.[119] In particular, Wisconsin waived the required state environmental impact statements, although the corporation must still obtain CAA and various water permits.[120]

The state allowed Foxconn to pay the state of Wisconsin for negative environmental impacts.[121] Foxconn submitted a proposal titled “Wetland Compensatory Mitigation In Lieu Fee,” which outlined how much damage the project would cause and how much Foxconn would pay to fill in wetland areas.[122] The proposal, which confirmed that the land set aside for the manufacturing plant was exempt from federal jurisdiction, calculated the environmental cost of construction to be at least one million dollars.[123] Foxconn proposed to pay the state $2,037,020 under a two-to-one ratio mitigation plan.[124] The plan itself was submitted April 16, 2018.[125] Wisconsin’s Department of Natural Resources determined that the project was available for exemption nine days later.[126] The state’s opinion letter only considered that the project was within the “Electronics and Information Technology Manufacturing Zone,” that the environmental damage was related to construction, and that Foxconn agreed to pay damages.[127] No environmental assessment was done other than Foxconn’s own assessment of monetary damages. Foxconn also procured an opinion letter from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which stated that the proposed site did not contain any navigable waters subject to federal jurisdiction, precluding the need for a NEPA evaluation or compliance with the CWA.[128]

The Foxconn controversy highlights the issue with tracking pollution in facilities not subject to U.S. regulations. The surrounding community showed widespread reluctance to allow Foxconn to set up a facility in Wisconsin after public assurances from the Trump administration that the company would be able to circumvent standard environmental regulatory procedures.[129] This uncertainty highlights the concern with facilities that produce in China—local communities do not have enough information to know what kind of pollutants each factory will emit.[130] Foxconn factories in China have been accused of violating environmental standards, although the corporation has always denied the allegations.[131] In 2013, Chinese regulators accused the company of dumping toxic heavy metals into local rivers.[132] Opponents of the Foxconn plant in Wisconsin fear this will happen again, as the plant will use heavy metals such as mercury to create LCD screens.[133] These concerns reflect the same concerns the EPA had in Warren Corp., applying different regulations for oil distributors that could not provide information about the environmental quality of their products.[134] The lack of information regarding foreign emissions and pollution is a major obstacle for regulating imported goods, and the individual emissions from one factory in China will not garner much public attention from Americans, even if the public is aware that there is a general pollution problem. However, applying the same lack of environmental information to a factory in the backyard of communities that have enjoyed improving environmental quality under statutes like the CWA highlights the significance of how much environmental destruction goes into imported products like iPhones.

III. Potential Solutions to Enforce More Stringent Environmental Standards on Domestic Corporations that Attempt to Use National Borders to Lower Costs and Raise Pollution

Even though the United States has limited tools to monitor and regulate products that eventually end up in the country, there are potential solutions that the government can implement to encourage domestic companies to hold foreign facilities and contractors to higher environmental standards. If the United States can craft legislation that is non-discriminatory, identifies specific environmental problems that affect U.S. jurisdictions, and targets those problems in a legitimate manner, it is possible to exercise more control over imported products, or at least obtain more data and information about their environmental impacts.

A. Past Solutions Have Been Proposed but Never Implemented, Primarily During the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments

Legislative history shows that Congress has considered the gap in environmental regulation in the past. In the Senate bill regarding the 1990 amendments to the CAA, senators from both sides of the aisle suggested mechanisms to enforce air quality policies overseas.[135] One senator attempted to introduce a duty on “any product imported in to the United States that has not been subject to processing . . . which does not comply with the air quality standards of the Clean Air Act.”[136] The senator, who had introduced the bill in hopes of preventing the CAA from lowering the marketability of U.S. manufacturing, did not specify how this amendment would be implemented.[137] This proposal also likely would have run afoul of the WTO’s subsequent panel decisions.[138] Likewise, another senator suggested a Pollution Deterrence Act that would have required the EPA to create an “International Pollution Control Index” for U.S. trading partners to compare their pollution standards to those in the United States.[139] Neither suggestion made it into law, likely because the amount of information that would be required to make these suggestions work would be enormous.

More recent solutions that could potentially address this problem are international in scale. The Paris Climate Agreement, for example, saw nearly every country in the world pledge to reduce its carbon emissions in order to stop irreversible effects on the planet.[140] The agreement requires consenting nations to “put their best efforts” into nationally determined contributions depending on each nation’s ability to reduce emissions.[141] As optimistic as the Paris Agreement is, it does very little to actually reduce carbon emissions. The agreement is entirely voluntary, and each nation has the ability to determine its own contribution.[142] There are no penalties or consequences for failing to meet goals.[143] The goals are also completely internal; one country may set higher goals for itself to reduce emissions but its trading partner may reduce carbon emissions at a much slower pace. Reliance on international agreements to help level the playing field on environmental regulations and emissions in importing countries does not provide any tangible solution. As the United States itself has demonstrated, nations can back out of the Paris Agreement.[144] If the United States wants tighter regulation on products coming into the country, international nonbinding agreements are not a strong legal option. Political pressure on countries to reduce emissions or spend more resources on enforcing regulation may be effective, but there is no immediate or guaranteed effect.

B. Legal Solutions for Enforcing Environmental Regulations on U.S. Companies may be Effective, but Must be Crafted in a Way that Does Not Overstep into Extraterritoriality or Threaten Global Trading Partners

Imposing stringent environmental regulations on the production of imported goods is difficult. International law protects the right of other countries, particularly developing countries, to trade with richer nations without discriminatory laws. As a practical matter, American agencies cannot exert the control or regulation over a foreign facility to account for emissions and waste.[145] Even if a manufacturer does violate environmental regulations, the government would not be able to gather evidence against the offending corporation in a foreign country with the same ease as that of a facility in the United States. This issue was demonstrated in Warren Corp., which showed that the EPA had difficulty acquiring emissions data from foreign gasoline refiners.[146] If the origin country does not require a manufacturer to provide data regarding its pollution and waste, that data may not exist.

1. The EPA May be able to Impose Civil Penalties and Mandatory Reporting on Imported Products

Despite the difficulty of imposing stringent environmental regulations on foreign governments or foreign corporations, many U.S. firms engaged in offshoring or outsourced production still have facilities in the United States. A lot of unregulated pollution comes from “intermediary goods,” like engines imported from China, to be assembled in North America.[147] Economists can use trade deficits to estimate what the pollution would have been if that particular product had been made in the United States, but they have no way of calculating the actual environmental cost of the product.[148] Adjustments to account for higher pollutive manufacturing can be made, but the data is often incomplete.[149] The intermediary product itself must be assembled with all of its components in the United States to produce the final product. In these cases, it may be possible to put the burden on the U.S. firm contracting for these goods to provide data. While the United States cannot force a foreign government to comply with its own regulations, it may be able to impose stricter regulations on firms that choose to locate production facilities in nations that have less stringent environmental regulations.

The first step for this solution would be to identify which countries have less stringent environmental regulations. This would require a list of countries and their policies towards pollution, similar to the “Pollution Deterrence Act” suggested to Congress in 1991.[150] While such a list would undoubtedly require a lot of resources to put together, other American initiatives have been able to do something similar with regards to child and human labor laws.[151] The list compilation from the Department of Labor relies on data and reports from a wide range of sources, including foreign governments, NGOs, and universities.[152] A similar report for environmental standards would probably be the type of pollution index congressmen in the 1990s were looking for—an index that would rely on third party data (i.e., not self-reporting data) that would assess foreign environmental performance. It would not parallel EPA self-reporting required under 40 C.F.R. § 98.[153] The reporting would also be a passive action and would require further legislation to either impose duties or taxes on imported goods identified in the report or ban them altogether. The identification of high-polluting countries, products, or even specific companies or factories would allow the EPA to tailor new requirements to certain industries.

Because increased pollution is not considered to be a violation of law the same way human trafficking is, it would be much more difficult to outright ban products that come from factories with inadequate environmental standards, unlike products that are made in violation of forced or child labor. The United States has declared that Section 307 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. § 1307) prohibits the importation of “. . .merchandise mined, produced or manufactured, wholly or in part in any foreign country by. . .forced or indentured child labor… ,” including forced child labor.[154] Such merchandise is subject to exclusion and seizure, and may lead to criminal investigation of the importer(s).[155] But as the WTO has reiterated, countries with lower environmental quality standards cannot be held in violation of another country’s law for failing to meet certain regulatory standards.[156] It would also be impossible to impose criminal sanctions on importers even if this were feasible. In practice, the laws preventing forced labor are difficult to implement simply because of the international component in attempting to police activities occurring outside of America’s borders. The list in question is a required document under the 2005 Trafficking Act and has not prevented identified goods from entering the country, as evidenced by bills passed during President Obama’s tenure.[157]

However, the resources that have gone into identifying goods that come from forced labor around the world show that it is not impossible to at least identify countries, corporations, or even specific factories that emit too much pollution.[158] The Department of Labor’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs is able to compile data from around the world in every industry regarding worker treatment.[159]

There is also the issue of discriminatory treatment. Even if the United States identified countries significantly out of compliance with environmental regulations or norms, singling out countries would trigger the WTO’s GATT provisions that enforce an even playing field.[160] While the gathering of information would not be at issue in front of the WTO, any attempts to enforce trade barriers on specific countries would be at issue.[161] The provision itself would have to be non-discriminatory in order comply with international custom.

2. The United States May be able to Ban or Create Embargos on Products that Cause Pollution, so long as the Pollution can Rationally be Attributed to Environmental Deterioration in the United States Itself

International law and customs have not completely prevented individual nations from controlling imports and exports based on environmental concerns. Even though the United States lost Shrimp-Turtle, the reason was not that it lacked authority under the Endangered Species Act.[162] Instead, the WTO acknowledged that the United States could create laws designed to protect endangered species residing in its waters through trade restrictions.[163] This departs from previous cases, which emphasized a clear separation between a state’s ability to ban products of a certain quality as opposed to products made by processes of a certain quality.[164] So long as the importing country can rely on a “sufficient nexus” to establish its jurisdiction over a regulated entity, the law may qualify as an exception to impermissible trade constraints.[165]

The other advantages to analyzing air pollution are its ubiquity and its role in global issues like climate change.[166] Air pollutants such as carbon dioxide do not remain localized. The effects of increased air pollutants are a global phenomenon that affects every country in the world. This may be too attenuated to count as an issue that the United States has jurisdiction over. On the other hand, the EPA has instruments in place to monitor the movement of pollution.[167] Technology and science are improving the tracking of how human activity affects the environment. This may make it easier to determine how production in one part of the globe affects a country in another part of the globe. Because countries have the right to consider environmental effects in their own territories, certain processes that adversely affect the atmosphere—or the oceans—may be the jurisdictional hook to impose limitations on foreign imports.

In crafting enforceable legislation, the United States would need to provide empirical data to connect a certain activity to environmental consequences under its authority in the United States. In Shrimp-Turtle, the United States acted under the Endangered Species Act, which had listed five turtle species that migrated in U.S. waters.[168] With regards to emissions, the CAA and its imposition of air pollutant goals would be an ideal hook.[169] By showing that certain processes emit more pollutants than are permitted by U.S. statutes, and that such actions can affect U.S. air quality, it may be possible to impose a ban or restriction on certain goods or products.

Supposing this hurdle is cleared, the United States may also be able to impose penalties on U.S. corporations that use products that do not comply with EPA regulations. If the CAA, for example, was amended to expand the EPA’s jurisdiction to inspect goods produced outside the United States, the EPA would have the ability to require reports and data on the production of each product. Foreign-produced goods would need to have an emissions threshold that manufacturing corporations must to comply with. At that point, the agency could apply standard enforcement proceedings under the CAA, including the ability to subpoena information and the ability to impose civil fines.[170]

C. Non-Legal Solutions such as Public Pressure May Facilitate Greater Accountability

The proposal for a list of countries, companies, or facilities that do not comply with certain environmental regulations is also useful to put social and political pressure on U.S. companies that outsource production. However, public attention is fleeting and rarely changes company behavior. Companies like Nike Inc. gained media attention in the 2013 collapse of the Ranza Plaza in Bangladesh.[171] This spurred public pressure and boycotting against the textile giant to rethink its overseas labor policies, but it still took four years for Nike Inc. to raise labor standards.[172] Public attention to these issues quickly faded and did not actually result in change.[173] Apple Inc. itself recently committed to clean energy in China, and encouraged its various suppliers to commit as well.[174] But while companies cited “growing ‘awareness’ [of clean energy] among consumers,” the shift to clean energy likely had to do with the Chinese government’s decision to reduce pollution and push a more environmentally-friendly agenda.[175] Social incentives for corporations may be useful to incentivize more sustainable outsourcing, but there is no guarantee that simply naming and shaming companies would work.

There are legal, international, and logistical barriers to enforcing environmental regulations on companies that choose to source products from countries that have lower environmental standards, or simply do not have the resources to enforce those regulations. The EPA has authority to monitor pollution within the United States, but foreign facilities are outside its jurisdiction and are difficult to monitor. The United States. has previously attempted to control processes from foreign nations by creating importation bans, but international trade law bars nations from imposing outright embargoes on goods that are produced with substandard environmental regulations. An exception exists, however, for goods that may damage the importing country’s environment, and this is where energy should be spent to enforce regulation. If the United States can create universal regulations that require importers to monitor production, how these products are created, and the emissions and pollution that result, it can enforce obligations solely on U.S. companies without running afoul of the WTO or other diplomatic limitations.

- * J.D. Candidate, 2020, University of Colorado Law School The author would like to thank her family and friends for their support, and the hardworking staff of the Colorado Natural Resources, Energy and Environmental Law Review for the work they put into publishing this Note. ↑

- Jaro Mayda, Environmental Legislation in Developing Countries: Some Parameters and Constraints, 12 Ecology L. Q. 997, 1006–07 (1985). ↑

- Christine Sansevero, The Effect of the Clean Air Act on Environmental Quality: Air Quality Trends Overview, 14 Pace Envtl. L.R. 31, 31 (1996). ↑

- See id. ↑

- Envtl. Prot. Agency, EPA-454/R-96-007, National Air Pollutant Emission Trends, 1900-1995, 1 (1996). ↑

- Jonathan H. Adler, The Fable of the Burning River, 45 Years Later, Wash. Post (June 22, 2014, 11:56 AM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2014/06/22/the-fable-of-the-burning-river-45-years-later/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.7689f2dcad21. ↑

- EPA History, EPA, https://www.epa.gov/history (last visited Oct. 18, 2019). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Envtl. Prot. Agency, supra note 4. ↑

- Sansevero, supra note 2. ↑

- Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, EPA, https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions (last visited Oct. 18, 2019). ↑

- Satish Joshi et al., Estimating the Hidden Costs of Environmental Regulation, The Acct. Rev. 171, 172 (2001). ↑

- Arik Levinson, Technology, International Trade, and Pollution from US Manufacturing, 99 Am. Econ. Rev. 2177, 2180 (2009) (explaining that the U.S. manufacturing output increased by twenty-four percent from 1987 to 2001 as common air pollutants decreased); Martin Neil Baily & Barry P. Bosworth, US Manufacturing: Understanding Its Past and Its Potential Future, 28 J. Econ. Persp. 3, 10 (2014). ↑

- Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, supra note 10. ↑

- The trade deficit with China, in particular, increased sharply from the 1980s to the 2010s. Baily & Bosworth, supra note 13, at 12, 16–17. ↑

- Huiyo Zhao & Robert Percival, Comparative Environmental Federalism: Subsidiarity and Central Regulation in the United States and China, 6 Transnat’l Envtl L. 531, 545 (2017). ↑

- See Joshi et al., supra note 11, at 172 n.1 (explaining that while certain manufacturing industries, such as the steel industry, placed significant blame on environmental regulations, even the harshest critics acknowledged that foreign competition also contributed to the decline of domestic manufacturing). ↑

- Arik Levinson, Offshoring Pollution: Is the United States Increasingly Importing Polluting Goods?, 4 Rev. Envt. Econ. & Pol’y 63, 66 (2010). ↑

- See Huifang Cheng et al., The Empirical Analysis on the Influence of CO2 Emission Regulation on the Export Transformation of Chinese Manufacturing Industries, 73 J. Coastal Res. (Special Issue) 209, 209 (2015) (explaining that carbon emissions in China, for example, quadrupled from 1973 to 2011). ↑

- See Joshi et al., supra note 11, at 172 n.1 (explaining that, for example, the steel industry suffered from competition from Japan and Korea at the same time it lost profits to environmental regulations). ↑

- M. Scott Taylor, Unbundling the Pollution Haven Hypothesis, in The Economics of Pollution Havens 1, 5 (Don Fullerton ed., 2006). ↑

- Id. ↑

- See Arik Levinson & M. Scott Taylor, Unmasking the Pollution Haven Effect, 49 Int’l Econ. Rev. 223, 249 (2008); Levinson, supra note 12 at 2177–78. ↑

- Cecile Daurat, Trade War or Not, U.S. Companies Follow the Consumer to China, Bloomberg (Aug. 28, 2019, 2:16 PM), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-08-28/trade-war-or-not-u-s-companies-follow-the-consumer-to-china. ↑

- Adam B. Jaffe & Karen Palmer, Environmental Regulation and Innovation: A Panel Data Study, 79 Rev. Econ. & Stat. 610, 617–18 (1997). ↑

- Carol McAusland, Environmental Regulation as Export Promotion: Product Standards for Dirty Intermediate Goods, in The Economics of Pollution Havens 150, 152 (Don Fullerton ed., 2006). ↑

- See id. ↑

- See id. ↑

- Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, supra note 10. ↑

- See Levinson, supra note 12, at 2177. ↑

- Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, supra note 10. ↑

- Id. ↑

- See id. ↑

- See generally Partner Government Agencies Import Guides, U.S. Customs & Border Prot. (Sept. 16, 2019), https://www.cbp.gov/trade/basic-import-export/e-commerce/partner-government-agencies-import-guides# (listing all agencies that regulate imports). ↑

- See generally Laws and Executive Orders, EPA (Sept. 14, 2019) https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/laws-and-executive-orders (listing all of the EPA’s sources of authority). ↑

- Clean Air Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 7412–7414 (2018). ↑

- 42 U.S.C. §§ 7413–7414 (2018). ↑

- 42 U.S.C. § 7604 (2018). ↑

- 42 U.S.C. § 7414 (2018). ↑

- 40 C.F.R. § 98.171 (2018); 40 C.F.R. § 98.251 (2018). ↑

- Iron and steel manufacturers, for example, must report on CO2, CH4, and N2O emissions from each stationary combustion unit in a facility. 40 C.F.R. § 98.172 (2018). ↑

- 40 C.F.R. § 98.2 (2018). ↑

- EPA importation of vehicles and engines, for example, focuses on the emission output a vehicle will emit once it enters the United States. It does not account for how the product was originally manufactured. See Envtl. Prot. Agency, EPA-420-B-11-015, Overview of EPA Import Requirements for Vehicles and Engines (2011). ↑

- Significance of Int’l Transp. of Air Pollutants Comm. et al., Global Sources of Local Pollution: an Assessment of Long-Range Transport of Key Air Pollutants to and from the United States 12 (2010). ↑

- U.S. Const. art. I, § 10, cl. 2. ↑

- World Trade Org., WTO in Brief 6 (2018). ↑

- Id. at 1. ↑

- Id. at 10. ↑

- Jeffrey L. Dunoff, Institutional Misfits: The GATT, the ICJ & Trade-Environment Disputes, 15 Mich. J. Int’l L. 1043, 1049–50 (1994). ↑

- Id. at 1050. ↑

- World Trade Org., supra note 45. ↑

- Membership, Alliances and Bureaucracy, WTO, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/org3_e.htm#join (last visited Oct. 18, 2019). ↑

- World Trade Org., supra note 45, at 10. ↑

- United States of America and the WTO, WTO, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/usa_e.htm (last visited Oct. 18, 2019). The United States was also a member of the WTO’s predecessor. Id. ↑

- Understanding the WTO: Settling Disputes, WTO, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/disp1_e.htm. (last visited Oct. 18, 2019). ↑

- Id. ↑

- 19 U.S.C. § 4201 (Supp. V 2018). ↑

- 19 U.S.C. § 3533 (2018). ↑

- General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, Oct. 30, 1947, 55 U.N.T.S. 262 [hereinafter GATT]. ↑

- George E. Warren Corp. v. EPA, 159 F.3d 616, 619 (D.C. Cir. 1998); Panel Report, United States—Standards for Reformulated and Conventional Gasoline, ¶¶ 8.1, 8.2, WTO Doc. WT/DS2/R (adopted Jan. 29, 1996) [hereinafter U.S.-Gasoline]. ↑

- Warren Corp., 159 F.3d at 618–19; U.S.-Gasoline, supra note 59, at § 2.11. ↑

- Warren Corp., 159 F.3d at 619. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 620. NOx was the primary pollutant the EPA was concerned with. ↑

- See Appellate Body Report, United States—Import Prohibition of Certain Shrimp and Shrimp Products, WTO Doc. WT/DS58/AB/R (adopted Oct. 12, 1998) [hereinafter Shrimp-Turtle]. ↑

- Id. at 2. ↑

- Id. at 1. ↑

- See id. at 70–71. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 76. ↑

- Id. at 71, 76. ↑

- Id. at 70–71. ↑

- GATT, supra note 58, at 562. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Shrimp-Turtle, supra note 65, at 51. ↑

- GATT, supra note 58, at 562. ↑

- Mexico etc versus US: ‘tuna-dolphin,’ WTO, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/envir_e/edis04_e.htm. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Shrimp-Turtle, supra note 65, at 50–51. ↑

- GATT, supra note 58, at 583–85. ↑

- Mexico etc versus US, supra note 77; Appellate Body Report, United States—Measures Concerning the Importation, Marketing, and Sale of Tuna and Tuna Products, 13-14, WTO Doc. WT/DS381/AB/RW/USA (adopted Dec. 14, 2018) [hereinafter U.S.-Tuna]. ↑

- Id. at 24. ↑

- Id. at 13. ↑

- See DS381: United States — Measures Concerning the Importation, Marketing and Sale of Tuna and Tuna Products, World Trade Org. (Jan. 11, 2019), https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds381_e.htm. ↑

- U.S.-Tuna, supra note 84, at 101. ↑

- Id. at 111. ↑

- Id. at 110. ↑

- Id. at 101. ↑

- See Baily & Bosworth, supra note 12, at 13. ↑

- Id. at 3. ↑

- Zachary A. Wendling et al., Yale Ctr. for Envtl. Law & Policy, 2018 Environmental Performance Index vi, 6 (2018). ↑

- Id. at 15. ↑

- Id. at 46. ↑

- Alex L. Wang, Explaining Environmental Information Disclosure in China, 44 Ecology L.Q. 865, 876 (2018). ↑

- Baily & Bosworth, supra note 12, at 4–5. ↑

- Cheng, supra note 17, at 209. ↑

- Baily & Bosworth, supra note 12, at 4. ↑

- Id. at 16. ↑

- Id. ↑

- International Trade and Market Access Data, WTO, https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/statis_bis_e.htm. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Yen-Ching Chang & Nannan Wang, Environmental Regulations and Emissions Trading in China, 38 Energy Pol’y 3356, 3363 (2010). ↑

- Zhao, supra note 15, at 532. ↑

- Id. at 548. ↑

- Id. at 545. ↑

- Id. at 545–46. ↑

- Jianglong Zhang et al., Has China been exporting less particulate air pollution over the past decade? 44 Geophysical Research Letters 2941, 2941 (2017). ↑

- See Transboundary Air Pollution, EPA (March 11, 2019), https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/transboundary-air-pollution. ↑

- Significance of Int’l Transp. of Air Pollutants Comm. et al., supra note 43, at 82; Joseph Kahn & Jim Yardley, As China Roars, Pollution Reaches Deadly Extremes, N.Y. Times (Aug. 26, 2007), https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/26/world/asia/26china.html; Zhang, supra note 111, at 2941. ↑

- Wang, supra note 97, at 876. ↑

- Brenda Groh, China Says Pollution Inspectors Find Firms Falsifying Data, Reuters (Mar. 30, 2017), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-pollution-idUSKBN17207B. ↑

- Ivan Moreno, What are the Environmental Concerns Surrounding the Wisconsin Foxconn Plant?, Chicago Tribune (Aug. 26, 2017), https://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-foxconn-wisconsin-plant-environmental-issues-20170826-story.html. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- 2017 Wis. ALS 58. ↑

- Environmental Requirements and the Foxconn Project, Wisconsin Dep’t of Nat. Res., https://wisconnvalley.wi.gov/Documents/environfaq.pdf (last visited Mar. 15, 2019). ↑

- Letter from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources to SIO International, Wisconsin, Inc. (Apr. 25, 2018), available at https://dnr.wi.gov/Business/documents/Foxconn/WetlandMitigationLetter20180425.pdf. ↑

- Letter from SIO International to Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (Apr. 16, 2018), available at https://dnr.wi.gov/Business/documents/Foxconn/InLieuFeePackage20180416.pdf. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Apr. 25, 2018 Letter, supra note 120; see also Letter from SIO International to Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (Sep. 27, 2018), available at https://dnr.wi.gov/Business/documents/Foxconn/ILFRequestPackage20180927.pdf (showing that Foxconn submitted subsequent proposals with substantially similar value regarding parcels of land that were not in the original proposal); see also Letter from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources to SIO International, Wisconsin, Inc. (Oct. 11, 2018), available at https://dnr.wi.gov/Business/documents/Foxconn/ILFResponse20181011.pdf (showing that Wisconsin granted the supplemental proposal soon after). ↑

- Apr. 25, 2018 Letter, supra note 120. ↑

- Letter from Marie Kopka, Lead Project Manager, Corps of Engineers, to Richard Reaves, CH2M (Oct. 5, 2018), available at https://dnr.wi.gov/Business/documents/Foxconn/ACOELetter20181005.pdf. ↑

- See Sarah Okeson, Foxconn Gets A Pollution Pass For Its Wisconsin Factory, DC Report (Aug. 14, 2018), https://www.dcreport.org/2018/08/14/foxconn-gets-a-pollution-pass-for-its-wisconsin-factory/. ↑

- See id. ↑

- Lulu Yilun Chen and Yu-Huay Sun, Foxconn Denies Pollution Accusations Amid Probe in China, Bloomberg (Aug. 5, 2013), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-08-05/foxconn-denies-pollution-accusations-amid-probe-in-china; Rik Myslewksi, Chinese Apple suppliers face toxic heavy metal water pollution charges, The Register (Aug. 5, 2013), https://www.theregister.co.uk/2013/08/05/chinese_apple_suppliers_investigated_for_water_pollution/. ↑

- Myslewski, supra note 130. ↑

- Moreno, supra note 115. ↑

- See Warren Corp., 159 F.3d. at 619. ↑

- Levinson, supra note 17, at 66; 136 Cong. Rec. S2337 (1990) (amendments submitted for the Clean Air Act). ↑

- 136 Cong. Rec. S2340 (1990) (statements of Sen. Slade Gorton). ↑

- Levinson, supra note 17, at 66; 136 Cong. Rec. S2340 (1990) (statements of Sen. Slade Gorton). ↑

- See Shrimp-Turtle, supra note 65, at 51. ↑

- S. 984 102nd Cong. (1st Sess. 1991). ↑

- The Paris Agreement, https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Trump will Withdraw From the Paris Agreement, N.Y. Times (June 1, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/01/climate/trump-paris-climate-agreement.html (noting, however, that it will take nearly four years for the United States’ withdrawal to become official). ↑

- See U.S.-Gasoline, supra note 59. ↑

- Warren Corp., 159 F.3d at 619. ↑

- Ian Austen, A Chevy with an Engine from China, N.Y. Times (Mar. 26, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/26/business/worldbusiness/26chevy.html. ↑

- Levinson, supra note 12, at 2185, 2190. ↑

- Id. at 2186. ↑

- International Pollution Deterrence Act, S.984, 102nd Cong. (1991). ↑

- 2018 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, DOL, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ILAB/ListofGoods.pdf. ↑

- Id. ↑

- 40 C.F.R. § 98 (2018). ↑

- 19 U.S.C. § 1307 (2017). ↑

- Id.; Alana Heller, Obama Signs Law Banning Imported Goods Produced by Forced Labor, NBC News (Feb. 25, 2016), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/obama-signs-law-banning-imported-good-produced-force-labor-n525901. ↑

- Mexico etc versus US, supra note 77. ↑

- See Current Federal Laws, Polaris, https://polarisproject.org/current-federal-laws. (las visited Nov. 4, 2019); See Heller, supra note 154. ↑

- See Trade Negotiation & Enforcement, Bureau of Inter. Labor Affairs, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/our-work/trade. (last visited Nov. 5, 2019). ↑

- See Id. ↑

- GATT, supra note 58. ↑

- Shrimp-Turtle, supra note 65, at 72. ↑

- Id. at 54. ↑

- Id. at 55. ↑

- Mexico etc versus US, supra note 77. ↑

- Barbara Cooreman, Global Environmental Protection Through Trade: A Systematic Approach to Extraterritoriality 23, 109 (2017). ↑

- Significance of Int’l Transp. of Air Pollutants Comm. et al., supra note 43, at 12. ↑

- Transboundary Air Pollution, supra note 112. ↑

- Shrimp-Turtle, supra note 65, at 2. ↑

- See generally 42 U.S.C. § 7414 (2018). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Ashley Westerman, 4 Years After Rana Plaza Tragedy, What’s Changed For Bangladeshi Garment Workers?, NPR (Apr. 30, 2017), https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2017/04/30/525858799/4-years-after-rana-plaza-tragedy-whats-changed-for-bangladeshi-garment-workers. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Ralph Jennings, Why These Contractors had to Help Apple Cut Air Pollution in China, Forbes (Jul. 31, 2018), https://www.forbes.com/sites/ralphjennings/2018/07/31/why-these-contractors-had-to-help-apple-cut-air-pollution-in-china/#581ee6773e07. ↑

- Id. ↑

Jordan Becker[1]*

Table of Contents

Introduction 102

I. U.S. Industrial Emissions have Decreased, but Overseas Manufacturing is Not Accounted for 103

II. Current Laws and Regulations Provide Little Environmental Oversight on Imported Goods 107

A. U.S. Environmental Laws Grant Agencies Limited Authority over Imported Goods 108

B. The World Trade Organization Limits any Country’s Ability to Regulate Foreign-Produced Goods 109

1. 1996: US-Gasoline 111

2. 1998: Shrimp-Turtle 112

3. 2018: US-Tuna 113

C. The United States Lacks Reliable Information Regarding Pollution and Emissions that Originate Beyond its Borders, as its Trade Relationship with China Demonstrates 115

III. Potential Solutions to Enforce More Stringent Environmental Standards on Domestic Corporations that Attempt to Use National Borders to Lower Costs and Raise Pollution 121

A. Past Solutions Have Been Proposed but Never Implemented, Primarily During the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments 121

B. Legal Solutions for Enforcing Environmental Regulations on U.S. Companies may be Effective, but Must be Crafted in a Way that Does Not Overstep into Extraterritoriality or Threaten Global Trading Partners 123

1. The EPA May be able to Impose Civil Penalties and Mandatory Reporting on Imported Products 123

2. The United States May be able to Ban or Create Embargos on Products that Cause Pollution, so long as the Pollution can Rationally be Attributed to Environmental Deterioration in the United States Itself 125

C. Non-Legal Solutions such as Public Pressure May Facilitate Greater Accountability 127

Conclusion 128

The world is becoming increasingly interconnected, and our understanding of climate change and pollution now expands beyond the borders of individual countries. Even when the United States monitors and regulates its own contribution to emissions and pollution, these pressing issues are impossible to control through domestic regulation alone. Many goods consumed by Americans are produced overseas. Federal agencies have the ability to regulate the kinds of products that come into the country, yet these agencies have little control over the methods by which those products were produced—even if they were manufactured in a far more environmentally destructive manner than the laws of the United States permit.

Major discrepancies still exist between pollution outputs created in developed countries and outputs from developing countries. Many developing countries have environmental laws and regulations in place, but often do not have the resources to enforce them.[2] As a result, there is an inevitable gap between the process quality of products and materials that are produced in developing countries compared to those produced in countries with structured environmental agencies like the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”). This Note will focus on ways the U.S. government can close loopholes in environmental regulation and policy to ensure companies that manufacture products overseas do so in an environmentally conscious manner.

First, simply calculating emissions within the borders of the United States does not accurately reflect the nation’s carbon footprint because it does not account for the manufacture of goods produced overseas for U.S. companies and consumers. Second, various legal barriers, both domestic and international, limit the ability of the United States to monitor and regulate the manufacturing process abroad. This Note will analyze China’s manufacturing relationship with the U.S. in the 2000s, and how China’s lack of environmental regulations and pollution data continues to affect the United States. Finally, there are several potential solutions through which the United States can monitor and regulate imported products in ways that will not overstep its authority.

I. U.S. Industrial Emissions have Decreased, but Overseas Manufacturing is Not Accounted for

The 1970s marked a turning point for American manufacturing and environmental regulation.[3] Increased production and large-scale consumption in the twentieth century caused a sharp rise in pollution in the United States.[4] Air pollutants like carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen oxides reached a peak in 1970.[5] In heavily industrialized areas, catastrophic events such as the infamous Cuyahoga River fire in 1969 were visual reminders of how polluted rivers had become in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.[6] In response to numerous environmental disasters and mounting political pressure, Congress enacted several landmark statutes in the 1970s, including the Clean Air Act (“CAA”) and Clean Water Act (“CWA”), that created the groundwork for environmental regulation.[7] Additionally, Congress funded the EPA in 1970 as the regulatory body charged with executing environmental laws and regulations.[8]

Environmental regulation affected every facet of American life, including the manufacturing industry. Increased regulation and political scrutiny forced U.S. manufacturers and producers to reduce and mitigate pollution.[9] Due to these regulations, air and water quality within the U.S. improved significantly.[10] Emissions continued to decline into the twenty-first century.[11] But as the U.S. government began to implement and enforce environmental regulation, environmental and labor costs increased as well.[12] Although manufacturing continued to play a major role in the U.S. economy—indeed, the manufacturing sector’s value actually increased—employment in the manufacturing sector fell.[13]

Figure 1: The EPA has reported a steady decline in industry-related greenhouse gas emissions in the United States over the past several decades.[14]

At the same time, the country also saw a rise in the importation of goods and parts from developing countries.[15] Companies based in countries like the United States moved factories to developing countries such as China and Mexico.[16] These countries provided companies with factories, cheaper labor, and favorable laws.[17] These moves did not go unnoticed, and companies were accused of “offshoring” their manufacturing process, skirting around local laws that regulated labor and pollution.[18] Emissions rose in these developing countries, and it seemed as if the United States simply displaced the pollution its environmental laws attempted to eliminate.[19] There is evidence showing that higher environmental regulation and the existence of regulatory schemes like pollution abatement costs correlate with an industry shift to developing countries.[20] Some economists refer to the industrial shift towards developing countries as the “Pollution Haven Hypothesis.”[21] This economic hypothesis predicts that companies located in countries with stricter environmental regulations will move production to countries with looser environmental regulations, so long as there is not a barrier to trade between countries.[22] However, a plethora of other factors show that there was not a simple, direct relationship between the decline of pollution in a country like the United States and the increase of pollution in other countries.[23]

Growing consumer markets in developing countries, for example, meant that companies moved their factories and production lines to be closer to their new customers.[24] Changes in technology also contributed to the decrease of pollution emitted through industrial manufacturing, in no small part due to the regulations that significantly increased the costs associated with pollution.[25] The theory suggesting that countries with more stringent environmental regulations develop cleaner technology is called the “Porter Hypothesis.”[26] This economic theory suggests that innovative technologies are driven by regulation, as companies have the incentive to avoid penalties or abatement costs if their facilities do not meet a country’s environmental standards.[27] Once cleaner technology has been implemented, the theory states that governments that value product quality will favor the environmentally conscious product, and exports will increase.[28] Yet, even exporting countries with stringent environmental regulations, like the United States, still import a significant amount of goods from countries with lower environmental standards.

Manufacturing does not account for all the pollution and emissions produced by the United States. Most pollution comes from consumption, rather than production.[29] Driving cars, running trains and buses, and lighting and heating homes with fossil fuels produce a significant amount of pollution.[30] In 2016, twenty-eight percent of greenhouse gas emissions produced by the United States were from the transportation sector, and another twenty-eight percent were from electricity production.[31] Twenty-two percent of U.S. emissions were produced by the industrial sector.[32] Changes in pollution levels and the effects of environmental laws and changing technology are more apparent in the former two sectors because most of the emissions and waste from these sectors are created within the United States. However, the U.S. industrial sector does not account for all of the goods that were actually produced for the consumption of American residents.[33] The pollution produced to create, ship, and consume a product is harder to track in an increasingly global market.

II. Current Laws and Regulations Provide Little Environmental Oversight on Imported Goods

The EPA primarily executes the laws and regulations that govern pollution in the United States. These laws govern pollution production within the U.S., leaving a gap in regulation of production lines for American companies—the production of foreign imports. Although domestic and international laws can encourage American consumers and producers to import ethically sourced goods and products, these measures are limited and ineffective.

A. U.S. Environmental Laws Grant Agencies Limited Authority over Imported Goods

Congress has the ability to regulate international trade and imports, but its authority rarely extends to monitor the environmental impact that production of certain goods has on the environment. While Congress has given the Fish and Wildlife Service the ability to monitor the importation of non-native species and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association the authority to regulate imported seafood to ensure sustainable harvesting, the EPA has little to do with products that are produced outside of U.S. jurisdiction.[34]

The EPA has significant authority over activity within the United States. Congress authorizes the EPA to implement and enforce regulations that reduce emissions and waste through the CWA, the CAA, and the Toxic Substances Act.[35] Through these statutes, the EPA sets regulations that govern how much of each pollutant is reasonable, how much individual polluters can emit, and tools to enforce compliance.[36] The CAA, for example, gives the EPA authority to inspect facilities and impose civil and criminal penalties.[37] The CAA also allows the public to bring citizen suits, permitting individuals to directly sue a violator if the EPA does not take action.[38] The EPA also has the authority to mandate reporting.[39] The ability of the government to require companies to give information has significantly increased the agency’s understanding of emission and pollution, and allows for substantive measures to be taken based on that data. Like its other provisions, however, the EPA’s authority to gather information is limited to the United States.

The Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, for example, requires production facilities from petroleum refineries and iron and steel production to report emissions.[40] All facilities in the United States and on the continental shelf must report various emissions identified by the CAA, as well as carbon dioxide emissions, depending on the type of pollution typically emitted by the particular industry in which each facility operates.[41] On the other hand, the reporting requirement only extends to importers of “Coal based liquid fuels (subpart LL), Petroleum products (subpart MM), Industrial gases (subpart OO), Carbon dioxide (subpart PP), and Fluorinated GHGs [greenhouse gases] contained in pre-charged equipment or closed-cell foams (subpart QQ).”[42] All of these imports are fuels that will physically burn and release emissions in the United States. The regulation is not concerned with the emissions that foreign petroleum refineries will emit while producing such fuels. The government is concerned with pollution produced within the United States, but not pollution emitted anywhere else.[43]

The problem with this system, particularly regarding the CAA, is that pollution is ubiquitous. Regional air quality may vary for concentrated pollutants like particulate matter, but air pollutants can affect the globe regardless of where they are emitted.[44] The system ignores air pollution emitted by China while manufacturing goods destined for U.S. consumption. Expansion of what the EPA could regulate, or monitor at the very least, would be needed to assess the true environmental impact of the United States. However, a line of international case law and a lack of reliable information limits the ability of the United States to regulate the environmental quality of imports.

B. The World Trade Organization Limits any Country’s Ability to Regulate Foreign-Produced Goods

The United States has the ability to regulate what comes in and out of the country.[45] However, certain limitations apply when countries deal with foreign trade. One of these limitations is the anti-discriminatory provisions laid out by the World Trade Organization (“WTO”) for member states.[46] The WTO is an intergovernmental trading organization that oversees global trade agreements.[47] In addition to facilitating negotiation, the WTO also provides arbitration and acts as a neutral body to bring trade disputes between nations.[48] The WTO’s governing articles, known as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (“GATT”), prohibit countries from granting other countries special trading privileges.[49] This extends to “imported goods [that] will be accorded the same treatment as goods of local origin with respect to matters under government control, such as taxation and regulation.”[50] This provision limits a country’s ability to put restrictions specifically on the process in which certain goods are produced. One of the most important roles of the WTO is to prevent trade discrimination between countries.[51] This provision creates a difficult barrier for environmental import restrictions because discrimination can come in the form of bans on unethically produced or pollution-heavy materials. Traditionally, bans on the importation of materials harvested in an environmentally destructive manner have put underdeveloped countries at a natural disadvantage because they do not have the resources to develop cleaner methods of production.

Like in all international organizations, membership in the WTO is voluntary.[52] Currently, 164 countries hold membership.[53] The United States is a member of the WTO.[54] Member states that have agreements with each other can bring action against states whom they believe are acting illegally or against international agreements.[55] Unlike most international bodies, the WTO has enforcement mechanisms in place that usually come in the form of retaliatory trade embargoes.[56] The United States defers to the WTO as the “foundation of the global trading system.”[57] The federal government has a codified system for implementing dispute settlements in order to comply with the WTO’s decisions.[58] The WTO wields political and economic power, and the possibility of member countries enacting an embargo on a country that refuses to comply with a decision threatens a high price to pay.

Although the WTO concerns itself with protecting free trade, it does acknowledge that a country’s environmental concerns can take precedence in practices that may otherwise be considered discriminatory. GATT’s article XX provides “general exceptions” to the agreement, including measures “necessary to protect human, animal, or plant life and health,” so long as those measures are “not applied in a manner which would constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination between countries where the same conditions prevail.”[59] The following cases adjudicated by the WTO strove to clarify the provision.