“Balance, that’s the secret. Moderate extremism. The best of both worlds.”[2]

As a result of United States federal land policy in the early part of the country’s history, including the disposal of much of the federal land under the 1872 General Mining Law[3] and the granting of over 130 million acres to railroad companies,[4] much of the federal public land is scattered among various private land holdings throughout the country. This has made parts of the federal domain extremely difficult to manage. Edward Abbey’s quote above beautifully describes the ideal process under which to make difficult decisions. Collaboration is key, especially when various disparate groups are involved. Federal land exchanges can exemplify such pinnacles of collaboration: “Land exchanges provide a highly rational solution to an irrational land management situation.”[5] Agencies and the legislature conduct land exchanges with private parties to create a more uniform landscape of federal land and to make management easier and more efficient.

The Oak Flat deal is an example of a recent land exchange, approved in 2014 by the U.S. Congress as part of a larger national defense bill. However, the land exchange traded an area that has long been revered by nature lovers, rock climbers, and local Indian tribes to an international copper mining company with insufficient collaboration and very little balance between the parties. Although the ultimate exchange was in many respects an improvement on previous attempts, it provides a prime example of how much room for improvement there is in the land exchange process, particularly those approved by the legislature.

This note analyzes the strengths and weaknesses of the recent legislative land exchange between the federal government and Resolution Copper Mining (“Resolution”) in Arizona. It also argues that the legislative land process, while wholly legal, is deeply flawed, and should come to look more like administrative land exchanges, subject to a public interest finding, and judicially reviewable under the arbitrary and capricious standard.

This note begins by describing the area of land being transferred from the United States Forest Service (“USFS”) to Resolution, including the land’s significance both to the local population and to the mining company itself. It then details a brief history of United States mining law on public lands, particularly the 1872 General Mining Law, and explains the processes of and the differences between legislative and administrative land exchanges. The third section describes the legislative history and evolution of the Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act, including its ultimate passage as a rider on the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015. It focuses on the differences between the Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act of 2005, the first bill introduced in Congress, and the bill that was ultimately passed to demonstrate the evolution of the provisions. Finally, the fourth section argues that while the Oak Flat land exchange with Resolution is problematic, a copper mine is ultimately beneficial to the local and national economy. It also argues that the legislative land exchange procedure is profoundly flawed and should more closely follow the administrative land exchange procedure, despite Congress’s plenary property power.

Oak Flat is an unexpectedly lush desert riparian area with incredible environmental, recreational, and cultural values. Located in Queen Creek Canyon in Tonto National Forest (“TNF,” or the “Forest”), Arizona, it is currently the site of a sixteen-unit campground, and is used year-round by birders, bikers, and hikers.[6] Desert riparian habitat currently makes up less than 0.5 percent of Arizona, but these areas of the state support diverse communities of plants and animals and are home to between sixty and seventy-five percent of Arizona’s wildlife species.[7] Devil’s Canyon, a rich riparian area adjacent to Oak Flat, is home to at least fifty-two bird species, including the Common Black Hawk and the Peregrine Falcon, both Arizona species of concern.[8] The land is also a mecca for rock climbers—the lands hosted the Phoenix Bouldering Contest for fourteen years and now host the Queen Creek Boulder Competition.[9] The area features more than 700 roped climbing routes and over 1,000 bouldering problems.[10] Furthermore, some members of the San Carlos Apache tribe consider the area to be sacred. The site has served as a traditional gathering ground for acorns and herbs by the tribe, as well as a burial ground and a place to hold traditional ceremonies.[11] It is also the site of Apache Leap, where a group of cornered Apache warriors jumped off a cliff rather than be captured by the U.S. cavalry.[12]

Tonto National Forest is the fifth largest national forest in the country, comprising nearly three million acres of land in Arizona.[13] Established in 1905, one of the primary management goals of the forest is protecting the Forest’s water quality and managing habitat, including riparian areas, “to support and improve wildlife diversity.”[14] Riparian areas, such as the area at Oak Flat, account for 25,000 acres of the Forest.[15] Recreational opportunities abound throughout the forest, including bicycling, hiking, climbing, camping, and water activities, such as boating and swimming.[16] Tonto National Forest is particularly special because of its proximity to Phoenix, creating easy access to an “urban forest.”[17]

The Forest surrounds Superior, Arizona, the town closest to the site of the Resolution mine. Superior is at the most northern tip of what is known as the Copper Triangle, which extends from the Phoenix area to the Mexican border.[18] Copper was first discovered in the Superior area in 1870[19], with mining beginning in 1887.[20] Subsequently, Magma Copper Company (“Magma”) purchased a mine in the area in 1910 and by 1971 had the capacity to concentrate[21] 3,300 tons of ore each day.[22] However, the copper market is cyclical and copper mining is highly dependent on global and domestic copper demand and prices.[23] Magma discontinued its operation in 1982, citing declining copper princes and high operating costs.[24]

The area is valuable to many diverse groups, including for recreational, cultural, and economic purposes. However, the existence of such varied interests, particularly between the mining proponents and the parties who use the area for recreational or cultural purposes, has created conflicts.

III. An Overview of the 1872 General Mining Law and Land Exchanges

Both the 1872 General Mining Law and land exchanges are important vehicles for managing and utilizing federal public land in the United States. The 1872 General Mining Law allows United States citizens to explore for and mine minerals on federal public lands.[25] The law helped to settle the west and incentivized the development of important mineral resources.[26] Land exchanges allow the federal government, either through Congress or through an administrative agency, to transfer land from private ownership into the public domain for a variety of reasons, but often in order to better manage and protect existing public land and resources.[27]

A. The General Mining Law of 1872

The General Mining Law of 1872 (the “Mining Law”) opened United States public lands to the exploration, discovery, and mining of economic minerals. The law states that “all valuable mineral deposits in lands belonging to the United States . . . shall be free and open to exploration and purchase . . . .”[28] Under the Mining Law, the extraction of hardrock minerals (including copper, gold, silver, and lead)[29] from federal public lands does not require the payment of royalties to the federal government, unlike the extraction of oil, gas, and coal from the same lands.[30] The Mining Law allows a claimant who locates valuable minerals on public land to file a mining claim and remove the mineral resource from the land.[31] The holder of an unpatented claim must simply pay a yearly $100 claim maintenance fee[32], unless the claimant holds ten or fewer claims on public lands and conducts at least $100 worth of labor or improvements on the claim[33], in which case the maintenance fee is waived.[34] Claimants may apply for a patent for their claim, which passes title to the land from the federal government to the claimant.[35] Although it is possible to mine on unpatented land, a patent gives the owner unrestricted access to the land, including the surface estate and other resources on the land.[36] However, Congress imposed a moratorium on processing patent applications starting October 1, 1994.[37] That moratorium is currently still in place.

Land exchanges involve the transfer of public land from one owner to another, usually from public ownership into private hands, and vice versa. Land exchanges may be conducted under an administrative agency, such as the USFS or the Bureau of Land Management (“BLM”), based on authority delegated to the agency by Congress,[38] or by Congress itself.[39] Land exchanges provide the agencies with an opportunity to acquire land they normally would not have access to, given the agencies’ limited budgets for land acquisitions and limited authority to sell their lands.[40] They also allow agencies to acquire lands that will help them “improve land management, consolidate ownership, and protect environmentally sensitive areas,”[41] in addition to disposing of land that is more isolated or that would be more valuable in private hands.[42]

Most land exchanges are conducted administratively and must abide by a defined procedure.[43] Under the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (“FLPMA”), land exchanges conducted through the BLM or USFS are only permitted if the agency “determines that the public interest will be well served by making that exchange.”[44] When determining the public interest, the Secretary (of either the Department of the Interior or the Department of Agriculture) must “give full consideration to better Federal land management and the needs of State and local people, including needs for lands for the economy, community expansion, recreation areas, food, fiber, minerals, and fish and wildlife.”[45] The agency’s determination of what constitutes the public interest is subject to judicial reviewable under the arbitrary and capricious standard.[46] Additionally, the non-federal lands acquired by the Secretary must not be less valuable than the federal lands to be exchanged, if they were to be kept under federal ownership.[47] In other words, the land exchange must favor the federal government, or at least must equally benefit both parties.

Administrative action also requires adherence to the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (“NEPA”).[48] NEPA states that “all agencies of the Federal Government shall . . . include in every . . . major Federal action significantly affecting the quality of the human environment” an environmental impact statement (“EIS”) of the action, a record of unavoidable environmental effects of the action, and alternatives to the proposed agency action.[49] A NEPA EIS for agency action creates transparency in the administrative system and allows the public to access the environmental information considered by the agency. NEPA, however, is a procedural, not a substantive statute. The statute “does not mandate particular results, but simply prescribes the necessary process.”[50] Moreover, the Supreme Court has held that “NEPA merely prohibits uninformed—rather than unwise—agency action.”[51]

Conversely, legislative land exchanges have relatively little required procedure and there is little case law regarding land exchanges shepherded through by Congress. The NEPA procedure applies solely to administrative action.[52] Consequently, legislative land exchanges require neither NEPA compliance, nor the FLPMA public interest finding, nor the requirement of equal value between the parcels exchanged. Rather, under the Property Clause, Congress has plenary power to “dispose of and make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory or other property belonging to the United States.”[53] The U.S. Supreme Court has upheld this power on numerous occasions to be a power “without limitation.”[54] Ultimately, legislative land exchanges avoid all of the procedural requirements of administrative land exchanges.

IV. The Oak Flat Land Exchange

Although inclusion within a national forest affords land certain protections and privileges, Public Land Orders enable the federal government to withdraw a parcel of land from the public land to increase those protections “for a particular public purpose or program.”[55] In 1955, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed Public Land Order (“PLO”) 1229, which withdrew 760 acres at Oak Flat Picnic and Camp Ground [sic] “from all forms of appropriation under the public-land laws, including the mining but not the mineral-leasing laws,” reserving that area for use “as camp grounds [sic], recreation areas, or for other public purposes . . . .” The Oak Flat area was withdrawn “to protect the Federal Government’s interest in the capital improvements of the campground that exists there.”[56] It was one of twenty-four sites within Arizona’s national forests withdrawn under PLO 1229.[57] Subsequently, in 1971, President Richard M. Nixon issued PLO 5132, which modified PLO 1229 and opened Oak Flat Picnic and Campground to “all forms of appropriation under the public land laws applicable to national forest lands, except under U.S. mining laws.”[58] Unfortunately, PLO 5132 weakened some of the protection accorded the campground, essentially creating a loophole—the land was unable to be mined while under federal ownership, but became eligible for inclusion in an administrative or legislative land exchange.[59]

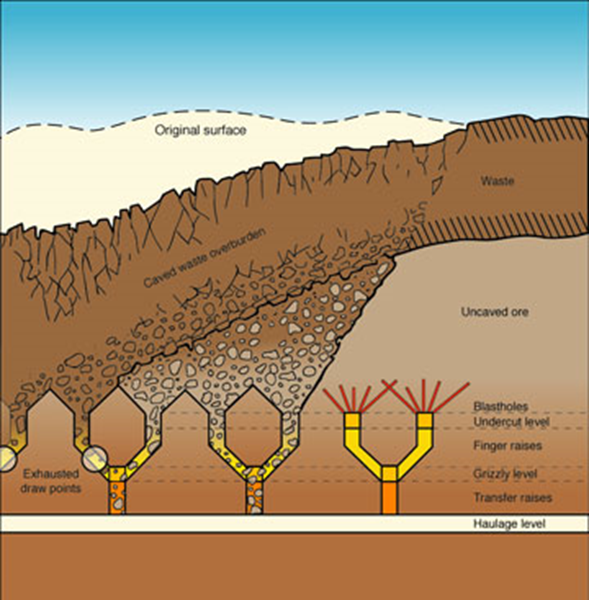

Enter Resolution Copper Mining, an international company formed by subsidiaries of Britain-based Rio Tinto PLC and the Australian company, BHP Billiton.[60] BHP Billiton acquired Magma Copper Company in 1996, forming BHP Copper Inc.[61] after the large copper ore body at the center of this debate was discovered in the early 1990s.[62] The deposit is estimated to contain 1.6 billion metric tons of 1.47 percent copper,[63] which equals approximately 23.5 million metric tons of copper. Resolution now owns and operates on land that was once part of Magma.[64] The ore will be removed using a method known as panel caving mining.[65] Because the ore is between 5,000 and 7,000 feet beneath the surface and is relative low-grade and dispersed, Resolution rejected open pit mining[66] for this particular project—too much earth would have to be removed.[67] The company determined that panel caving mining was the only practical and economical way to remove the ore based on “analyses of ore body shape, size, and location; properties of the rock; metal content and grade; depth of the mine; and costs to develop and mine the deposit.”[68] The panel caving mining technique allows large ore bodies to be mined by dividing it into panels and working on each panel successively until the entire ore body has been removed, using gravity to break up the rock. As the copper ore body is removed from the earth, the surface above the ore will collapse, causing subsidence throughout the area and eventually forming a crater.[69]

Figure 1. Panel caving mining method.[70]

This crater should start to develop four to eight years after mining begins and could ultimately be up to 1.8 miles wide and 950 feet deep. The first panel will be completed in approximately thirteen years and the entire ore body should take more than forty years to be mined completely.[71]

Resolution has already devoted considerable investments to this project, even before the passage of the land exchange. The company spent over $30 million restoring and updating infrastructure and facilities from the Magma mine.[72] Additionally, Resolution already holds mining claims on 1,662 of the 2,422 acres included in the land exchange—everything except the 760 acres at Oak Flat Campground that were ineligible for appropriation under PLO 5132.[73] It also holds a substantial amount of land surrounding the public lands in private ownership. As a result of the 1994 moratorium on patent applications and PLO 5132, Resolution was unable to patent its acreage or acquire mining rights to the Oak Flat land. However, the company found a way around that moratorium and prohibition.

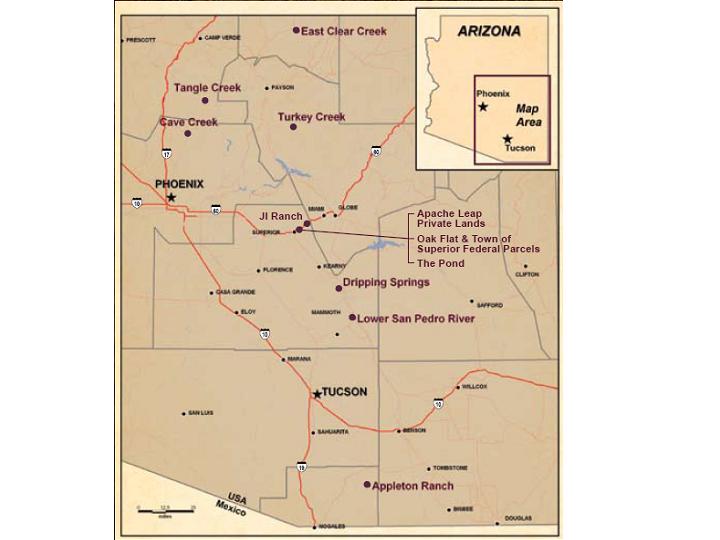

Figure 2. Land parcels involved in the Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act.[74]

Members of Congress began introducing legislation concerning Oak Flat in 2005 with the introduction of H.R.2618 and S.1122 (Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act of 2005) (the “SALECA” of 2005). Under those identical bills, the government would have conveyed 3,025 acres of national forest land to Resolution in exchange for approximately 4,814 acres owned by Resolution.[75] Neither bill passed.[76] Successive versions of the SALECA were introduced in subsequent Congresses (see Table 1). Altogether, members of Congress introduced bills proposing the land exchange seven times in the House and six times in the Senate. Only one actually passed its respective house on its own merits—H.R.1904 in 2011 with a 235 to 186 vote.[77]

Table 1. Legislative history of the land exchange.

| Year | Bill |

| 2005 | H.R.2618/S.1122 (Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act of 2005) |

| 2006 | H.R.6373/S.2466 (Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act of 2006) |

| 2007 | H.R.3301/S.1862 (Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act of 2007) |

| 2008 | S.3157 (Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act of 2008) |

| 2009 | H.R.2509/S.409 (Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act of 2009) |

| 2010 | H.R.4880 (Copper Basin Jobs Act) |

| 2011 | H.R.1904* (Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act of 2011) |

| 2013 | H.R.687/S.339 (Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act of 2013) |

| 2014 | H.R.3979* (Carl Levin and Howard P. “Buck” McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015) |

| 2015 | H.R.2811/S.2242 (Save Oak Flat Act) |

* = bill passed.

Congress is constitutionally permitted to conduct land exchanges. In the constitutional authority statement of H.R.687 (Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act of 2013), Representative Paul Gosar (R-AZ-4) cited Congress’s authority under Article IV, Section 3 of the Constitution[78] to manage property owned by the Federal Government, including the ability to “sell, lease, dispose, exchange, transfer, trade, mine, or simply preserve land.”[79] Representative Gosar cited Kleppe v. New Mexico, in which the Supreme Court held the Article IV power to be “without limitation.”[80] In the statement, Representative Gosar validated the land exchange, saying “a large commercial grade copper mine will be able to proceed with the attendant economic benefits . . . [and] the Federal Government also gains equally valuable land that has significance for other purposes.”[81] Senator John McCain (R-AZ) introduced an identical bill, S.339, to the Senate on February 14, 2013.[82] Both bills asserted that the 113th Congress found that the enactment of the land exchange would be in accordance with the FLPMA objectives—the SALECA would be in the public interest for a variety of economic, cultural, recreational, and social reasons.[83] However, neither bill passed.[84]

The land exchange ultimately passed in 2014 when it was included as a rider[85] on the Carl Levin and Howard P. “Buck” McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015 (the “NDAA”).[86] This note will hereinafter refer to the provision passed as a rider on the NDAA as the “Act.” The NDAA was a piece of “must-pass” legislation,[87] clearing in the House 300−119 on December 4, 2014, and in the Senate 89−11 on December 13, 2014.[88] Subsequently, President Barack Obama signed the bill into law on December 19, 2014.[89]

Although there is no set procedure for legislative land exchanges, the land appraisal process detailed in the Act generally follows a procedure similar to that required of administrative land exchanges. The Act requires the Secretary of Agriculture and Resolution to select a mutually acceptable appraiser[90] who will determine market value of the land parcels, considering “the highest and best use of the property to be appraised.”[91] Thus, the final market value of the federal parcel, including Oak Flat Campground, must include appropriate values for the recreational opportunities, valuable riparian habitat, and cultural values lost. The final appraisals of both the federal and the non-federal land will be made available to the public for review.[92]

Under the land exchange, Resolution will transfer eight separate parcels of land throughout Arizona, totaling approximately 5,300 acres, to the federal government.[93] Resolution purchased 7B Ranch and Turkey Creek in 2003, Tangle Creek, Appleton Ranch, Cave Cree, and J.I. Ranch in 2004, and the East Clear Creek parcel in 2005, intending to include the parcels as part of the land exchange.[94] These lands include a variety of ecosystems, including riparian lands surrounding the San Pedro River, mesquite bosques, woodlands, upper plateaus, and rich grasslands.[95] As shown in Figure 2, although the parcels are located throughout the state, many are unique in that they are private holdings surrounded by or intermingled with nationally or state protected areas. They support a wide variety of flora and fauna and some are areas that have been recognized as important bird areas.[96]

A. Evolution of the Land Exchange

There have been some important changes throughout the history of the successive bills, for better or worse. For example, on the one hand, under the passed Act the federal government was able to fully protect important Apache sacred land. On the other hand, the Act contained no explicit protection for or provisions to improve rock-climbing areas.

In the SALECA of 2005, if the appraised value of the Resolution land to be conveyed to the government exceeded the value of the Federal land to be conveyed to Resolution, the Secretary of the Interior was to pay the difference in value of the lands to Resolution.[97] Conversely, under the Act, any value assigned to Resolution land that exceeds the value of the federal land will be considered a donation to the United States by Resolution and will not need to be reimbursed.[98]

Additionally, the SALECA of 2005 established a conservation easement on the surface estate of Apache Leap, prohibiting surface development of the area and commercial mining extraction under the land.[99] Resolution would have maintained control of part of the Apache Leap area, retaining most of its private property rights,[100] but would have been limited in the amount of development that could have occurred on the land, as a result of the easement. On the other hand, under the Act, the south end of Apache Leap will be conveyed to the Secretary of Agriculture.[101] Apache Leap and the land acquired by the federal government through the exchange are withdrawn from “entry, appropriation, or disposal under the public laws,” as well as use under mining laws, similar to the original withdrawal of the Oak Flat Campground through PLO 1229.[102] The Apache Leap Parcel will be combined with about 110 acres acquired through the land exchange from Resolution to form the 807 acre Apache Leap Special Management Area (“SMA”).[103] This area is set aside “to preserve the natural character of Apache Leap[,] to allow for traditional uses of the area by Native American people[,] and to protect and conserve the cultural and archaeological resources of the area.”[104] This land will be entirely unavailable to mining or appropriation.[105] In order to protect Apache Leap, Resolution may need to limit the extent to which it mines the ore, ensuring that protected areas do not subside.[106] Additionally, in preparing the Apache Leap SMA management plan, TNF must assess the extent to which any additional considerations are “necessary to protect the cultural, archaeological, or historical resources of Apache Leap, and to provide access for recreation.”[107] The practical result of the two methods is the same—protection of Apache Leap. But although a conservation easement is a legally enforceable agreement[108] that would guarantee the protection of Apache Leap, the conveyance of Apache Leap results in a more secure and extensive protection for the land because the land will be transferred into federal hands.

Furthermore, the SALECA of 2005 did not provide for the preservation of the Oak Flat Campground.[109] Instead, a replacement campground would have been built, at least partly funded by Resolution.[110] The SALECA of 2005 also had a provision that would require the development of a replacement rock climbing area, also to be partly funded by Resolution.[111] Similarly, the Copper Basin Jobs Act (H.R.4880), introduced in 2010, contained a provision that required Resolution to pay the Secretary of Agriculture $1.25 million to improve recreational access and facilities in the State, including roads and trails.[112]

The final Act passed by Congress in the NDAA and signed into law by President Obama contains neither of these provisions or even anything similar. Although the Act withdraws and preserves Apache Leap, Resolution will not be required to fund a replacement campground or a replacement climbing area. The Oak Flat Campground will remain accessible to the public for a time, but only “to the maximum extent practicable” and only “until such time as the operation of the mine precludes continued public access for safety reasons, as determined by Resolution Copper.”[113] The rock climbing areas, the Campground, and the land on which they are situated will ultimately be lost.

B. Opposition to the Land Exchange

Not everyone involved with the project supported the land exchange. In a March 2013 hearing before the House Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources and Committee on Natural Resources, U.S. Forest Service Associate Chief Mary Wagner explained that the Department of Agriculture did not support the 2013 bill.[114] In particular, she stated that such reluctance was based on the lack of environmental review before the land exchange took place. Additionally, because of the religious and cultural importance of the land, Associate Chief Wagner focused on the need to consult with the affected tribes. She stressed the following:

[A]ny consultation would not be considered meaningful under Executive Order 13175,[115] “Consultation and Coordination with Indian Tribal Governments,” because the bill as introduced limits the Secretary’s discretion regarding the land exchange. The focus of the consultations would likely be the management of those areas over which the agency would have discretion, namely, the federal land adjacent to the mine and Apache Leap.[116]

The Act only requires consultation with tribal governments after the land exchange has already been passed.

Additionally, Associate Chief Wagner explained that the lack of review under NEPA was a problem: “An environmental review document after the exchange would preclude the U.S. Forest Service from developing a reasonable range of alternatives to the proposal and providing the public and local and tribal governments with opportunity to comment on the proposal.”[117] For example, it is unclear what effect the mine’s activities will have on either local or regional water supplies and quality.[118] This is of particular concern due to Arizona’s arid climate. According to the dissenting views expressed in the House Report of the Committee on Natural Resources, the Committee heard testimony that the project would require water in the amount of 40,000 acre-feet per year. For reference, this is the amount that Tempe, AZ, a city of approximately 160,000, uses annually.[119]

Resolution, on the other hand, claims that it will need at most 16,000 to 20,000 acre-feet annually, averaging about 12,000 acre-feet per year.[120] However, although mining is extremely water intensive, Resolution appears to be making enormous efforts to utilize best practices and to recycle and reuse water whenever possible.[121] Resolution reports that much of the water for the project will come from purchased banked water from the Central Arizona Project (“CAP”).[122] The remainder of the required water is currently being met by using treated water from the dewatering process.[123] So far the company has secured adequate water resources to sustain the mine for about half of its proposed lifetime.[124] Additionally, water used during the mining process is being treated, transported through pipelines, blended with CAP water, and used to irrigate Arizona farmland.[125]

Some Congressmen have also expressed dissatisfaction with the project. Following the passage of the land exchange as part of the NDAA, Representative Raúl Grijalva (D-AZ-3) introduced H.R.2811 in the House on July 1, 2015,[126] and Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) introduced S.2242 in the Senate on November 5, 2015.[127] These identical bills, known as the Save Oak Flat Act, seek to repeal Section 3003 on grounds that the rider circumvented the established passage procedure in the House and the Senate and shirked the federal government’s trust responsibility to protect tribal sacred lands located on federal lands.[128] The Save Oak Flat Act seeks solely to repeal Section 3003 of the NDAA, leaving the remaining sections of the defense act in place.[129] However, both of these bills died in committee.[130]

In 2015, the National Trust for Historic Preservation (“National Trust”), a privately funded nonprofit dedicated to saving the country’s historic places, particularly those that embody diverse cultural backgrounds, listed Oak Flat on its list of its annual “11 Most Endangered Places list.”[131] In particular, the National Trust cited the lack of adequate consultation with the area’s tribes.[132] Additionally, on January 21, 2016, the National Park Service (“NPS”) published a notice nominating Chi’chil Bildagoteel Historic District[133] for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (“National Register”).[134] The nomination received considerable backlash from certain lawmakers, particularly Representatives Gosar (who sponsored the original SALECA bills) and Ann Kirkpatrick (D-AZ-1). Representative Gosar went so far as to call the designation “bogus,” and accused the NPS of “attempt[ing] to silence public comments through deceptive notices and short comment periods.”[135] Representatives Gosar and Kirkpatrick also challenged the lack of specific location details in the nomination notification.[136] However, Vincent Randall, an Apache elder, responded that those contentions are ill-founded and that the location of sacred sites are “a closely guarded secret”; in particular that the location should not be broadcast so that they are protected from tourists and souvenir seekers that may ultimately destroy the site’s intrinsic religious value.[137] The Keeper of the National Register of Historic Places, Dr. Stephanie Toothman additionally responded in a letter to Representative Gosar, citing Section 304 of the NHPA as authority in restricting location information as “necessary and appropriate . . . to ensure the preservation of sites of traditional cultural significance to the San Carlos Apache Tribe and other tribes in the area.”[138] After the required comment period and following the required procedure, on March 4, 2016, NPS listed Oak Flat in the National Register.[139] The effects of this listing will be discussed below.

V. Some Good News, Some Bad News

At this point, players in the saga should be looking forward, not back. Even if an act similar to the 2015 Save Oak Flat Act survives Congress’s current dysfunction and is signed into law by the President, Resolution will likely still mine the deposit because Resolution owns land and holds mining claims throughout the area. Although the company claims that mining the copper deposit would be uneconomical without the land exchange,[140] it offers no explanation as to why. Perhaps because that simply is not the case. The deposit is too valuable not to mine, with or without the land exchange.

Because NPS listed Oak Flat as an historic site in the National Register, it does receive a slightly increased level of protection. After a site is listed, NPS regulations require that the federal agency responsible for the activity affecting the historic site (in this case the USFS) “provide the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation a reasonable opportunity to comment,” as required by Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (“NHPA”).[141] However, listing Oak Flat in the National Register will likely have little practical effect. Simply by following this “procedural requirement” and allowing the Advisory Council the opportunity to comment on the project, the USFS “may adopt any course of action it believes is appropriate.”[142] Listing the area does not stop the mine, although “stakeholders will have to thoroughly evaluate the impact on the historic site, which could add delays to the mine’s timeline.”[143]

However, that does not mean that all hope is lost. The legislative land exchange process can be improved prospectively, particularly if it is modeled after the administrative land exchange process, with its public interest standard and the availability of judicial review. In particular, this section argues that the Oak Flat land exchange should have further taken the following into consideration: economic impacts, particularly the jobs resulting from the project, the possibility of royalty payments, government-to-government consultation, and the need for a meaningful EIS. These are also areas where other legislative land exchanges could improve in the future. In addition, groups involved in the Oak Flat land exchange—both those advocating for the exchange and those protesting against it—should collaborate and listen to the other side’s input.

A. Legislative Land Exchanges Should Look More Like Administrative Land Exchanges—Suggestions for Change

A situation such as this will likely occur again. The loss of Oak Flat and the surrounding lands means the loss of an area brimming with cultural, recreational, and environmental diversity and importance. While the land exchange, the rider on the NDAA, and the entire process were technically legal, the procedure followed did not adequately ensure a fair and balanced outcome in which all affected parties were represented and taken into account. Despite Congress’s plenary power, there needs to be some sort of process similar to that for administrative land exchanges. In particular, there appears to be no explicit requirement that the land exchange be in the public interest, and there is little possibility of judicial review.

In 2001, the Sierra Club adopted a set of guiding principles regarding public land exchanges, both legislative and administrative.[144] Although the Sierra Club recognizes that land exchanges may be used as a valuable tool for land acquisition by the government, it favors acquisition by purchase, and generally does not support the transfer of environmentally sensitive lands out of public ownership.[145] Additionally, the Sierra Club recommends that both legislative and administrative land exchanges “comply with all applicable laws and regulations, and should be subject to full judicial review.”[146] If the exchange involves Native American land, it should “fully protect environmental values and respect Native American sovereignty and treaty rights.”[147] Congress should also ensure that the public interest is served through the land exchange by stipulating the inclusion of covenants, easements, and other sorts of restrictions on the land exchange, as Congress did here through the withdrawal and ultimate protection of Apache Leap.[148] Finally, the Sierra Club calls for full public participation in any land exchange and the assurance that legislative land exchanges will be “subject to the same standards of full environmental review, maximum public participation, and protection of citizen’s rights” as administrative land exchanges.[149]

Although administrative land exchanges are more efficient, they still have their own challenges, and theoretically, elected members of Congress should best be able to reflect the wishes of their constituents. The typical administrative land exchange takes eighteen months to four years to finalize.[150] The Oak Flat land exchange took nine years to pass. This is not to say that administrative land exchanges are immune to scandal. Past investigations by legal departments throughout the federal government have revealed administrative land exchanges that “fleeced taxpayers out of tens of millions of dollars and exchanges of federal land rich with natural and social resources in exchange for land that provided little or no public benefits.”[151] However, members of Congress, unlike heads of administrative agencies, are elected officials who are supposed to listen and respond to the wishes of their constituents. SALECA passed but once on its merits. Interestingly, however, Senator McCain has received campaign contributions from Rio Tinto affiliates and Senator Jeff Flake (R-AZ) worked as a paid lobbyist for a Rio Tinto mine.[152] Both Senators were heavily involved in the ultimate passage of the land exchange as a rider on the NDAA. Our elected officials should not be so obviously persuaded by contributions from interest groups. This clearly demonstrates why legislative land exchange should mirror the clear procedure required under administrative land exchanges. Despite the scandal involving some administrative land exchanges, the procedure is generally a good one.

Situations such as these are particularly difficult when there are multiple parties and interests involved. The administrative land exchange process is one way to navigate the interests of all parties because of the opportunity for public involvement and comment. Some proponents of the bill claim that the Oak Flat land exchange was included as a rider on the NDAA because a domestic supply of copper is a matter of national security. However, including the Act as part of a must-pass piece of legislation like the NDAA was a sneaky way around the traditional legislative process. Senator McCain’s false and misleading claims regarding its passage are particularly disturbing, including the following: “[t]he truth is, this land exchange legislation was a bipartisan compromise arrived at after a decade of debate and public testimony. It does not involve any tribal land or federally-designated ‘sacred sites.’”[153] While it may be true that the land included in the exchange is not owned by the area’s tribes as part of the reservation and does not contain any “official” sacred sites, that does not alter the land’s important cultural value. In fact, in direct contradiction to Senator McCain’s statements, the Forest Service has closed Oak Flat Campground at least twice—once in 2012 and once in 2014—to allow the San Carlos Apache tribe the use of the area for “traditional cultural purposes,” including “access to sacred sites for individual and group prayer and traditional ceremonies and rituals.”[154] Federal land is held in trust for all citizens and that trust is particularly relevant to the nation’s tribes. Moreover, Congress passed the NDAA, not the land exchange provision, with bipartisan support.

1. Domestic Economic Considerations

Resolution asserts that the mine will provide for 3,700 jobs in Arizona and bring in more than $60 billion to the state over the projects sixty-year lifespan.[155] Additionally, the company states that the project “has the capacity to deliver twenty-five percent of the copper needed in the United States.”[156] According to the U.S. Geological survey, copper is the third most used metal, in terms of quantities consumed, after iron and aluminum.[157] Approximately seventy-five percent of copper consumed is used for electrical purposes, including “power transmission and generation, building wiring, telecommunication, and electrical and electronic products.”[158] In 2015, the United States produced 1,250 thousand metric tons of copper from twenty-six mines.[159] That same year, the United States consumed 1,780 thousand metric tons, of which imported copper accounted for thirty-six percent.[160] It is estimated that there are approximately 3,500 million metric tons of undiscovered copper throughout the world, in addition to the 2,100 million metric tons of known copper reserves.[161] Copper production in Arizona accounts for approximately sixty-four percent of domestic copper.[162] As of 2006, as much as 230,000 tons of minerals were produced annually in Tonto National Forest alone.[163] Copper mining is, of course, subject to the effects of the global economy, often resulting in a series of boom and bust cycles. As a result, the global price of copper has significant effects on the amount of exploration and mining that occurs.

However, Resolution admits that the capacity of Arizona smelters currently in existence may be insufficient for the amount of copper that the mine will produce. The majority of the copper will be smelted outside of the United States,[164] taking away domestic economic opportunity. Furthermore, critics of the bill contend that Resolution has made no promises that the final products of the mine will ultimately remain in the United States, likely because China commands more than forty-five percent of the global demand for copper.[165] This negates at least part of the rationale behind the inclusion of the Act in the NDAA. Despite being a foreign corporation, instead of investing in the global economy, Resolution should attempt to focus on the U.S. economy. Considering the long timeline for the project, building smelters within Arizona, or even simply within the United States, would help create domestic jobs. This would provide an opportunity for Resolution to invest in the community, state, and country.

In addition to the impact on domestic jobs, the Act should have required royalty payments by Resolution. Under the 1872 Mining Law, miners and mining companies are not required to pay any sort of royalty to the federal government. Unlike most mining claims under the Mining Law, this project was highly publicized and recognized as likely to be extremely profitable. There is a known quantity of a very valuable mineral on federal land. Oil and gas are both subject to royalties when produced on federal land and this resource should be no different.

3. Consultation with Affected Indian Tribes

While the land exchange that passed contains a provision that requires the Secretary of Agriculture to consult with Indian tribes “concerning issues of concern to the affected Indian tribes related to the land exchange,”[166] this post-passage consultation is not enough. The listing of the area in the National Register further underscores the importance of this consultation. Although the designation may have little effect on the outcome of the land exchange, on the other hand, it also makes it harder to deny the area’s cultural and religious significance.[167] Particularly, this listing should encourage the USFS and Resolution to further consult with the San Carlos Apache and other tribes in the area.

However, the federal government’s trust responsibility to Indian tribes requires consultation before the passage of any land exchange bill, whether legislative or administrative. Congress’s plenary power under the Property Clause does not diminish that responsibility. Even after the completion of the NEPA EIS, the exchange between the Forest Service and Resolution will occur. To be meaningful, government-to-government consultation between the Forest Service and the tribes should have occurred prior to its passage. There is little evidence that consultation between governments actually even occurred, except for the withdrawal of Apache Leap from mining.[168] This was an important step because Apache Leap is considered to be a sacred site by some within the San Carlos Apache tribe. But the lands on which Oak Flat Campground and the surrounding areas are situated are no different. Former Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell echoed this sentiment in a statement regarding the inclusion of the land exchange in the NDAA after its passage. She expressed her profound disappointment with the provision, which she argues “short circuits the long-standing and fundamental practice of pursuing meaningful government-to-government consultation with the 566 federally recognized tribes with whom we have a unique legal and trust responsibility.”[169] Although Executive Order 13175,[170] like NEPA, applies only to federal agencies, Congress should also be bound by these requirements. If anything it is even more important for Congress to take into account the wishes and needs of Native Americans than it is for agencies to do so. Such consideration should be automatic.

The upcoming EIS process may be one avenue in which opponents of the land exchange may be able to gain some traction and affect some necessary change, or at least continue raising important points as to points that need to be addressed by the USFS and Resolution. If members of the public continue to believe, for example, after the required appraisal report is finalized, that the federal government did not receive land of equal or greater value to the land it exchanged with Resolution, they may use the opportunity to attempt to alter the final result of the exchange by contacting their congressional representatives and making comments.

Tonto National Forest (“TNF”) published the “Resolution Copper Project and Land Exchange EIS Scoping Report”[171] (“Scoping Report”) in March 2017. This scoping process is the first step in the process of completing an EIS, which would ultimately look at the environmental effects of all actions proposed by Resolution in its “General Plan of Operations” (GPO),[172] submitted in 2013, including the land exchange itself.[173] TNF received a total of 133,512 non-duplicate submittals during the public scoping process, amounting to 6,948 individual comments.[174] Primarily, public concerns pertained to the following: socioeconomic effects; subsidence; location of the tailings storage facility; contamination of groundwater and surface waters; impacts to biological resources, wildlife, and wildlife habitat; permanent impacts to tribal cultural resources; loss of recreational access and opportunities; threats to public health and safety; and impacts to scenery.[175] These concerns will be address in the proceeding EIS process.

In particular, the proximity of the mine to Apache Leap and Devil’s Canyon may change how people experience those areas recreationally, culturally, and spiritually.[176] Although the final passed Act protects Apache Leap, there is some concern that the presence of a working copper mine in the vicinity of the sacred area will disturb and diminish the very essence of its sacredness. John Welch, a professor at Simon Fraser University and a former historic preservation officer for the White Mountain Apache Tribe says the land included in the exchange “is the best set of Apache archaeological sites ever documented, period, full stop.”[177] The EIS required by the Act does little mitigate the situation. It should be noted that the EIS prepared by the USFS will affect the actions subsequent to the exchange, including “the granting of any permits, rights-of-way, or approvals for the construction of associated power, water, transportation, processing, tailings, waste disposal, or other ancillary facilities.”[178]

Additionally, most decisions made as a result of the EIS will only affect Resolution’s actions on Forest Service land, not on private land or on Forest Service land that has been conveyed to the company as a result of the land exchange. The Act does provide that the EIS will assess the impacts on cultural and archaeological resources on the land to be conveyed to Resolution, as well as on land that will remain in federal ownership.[179] The EIS must “identify measures that may be taken, to the extent practicable, to minimize potential adverse impacts on those resources, if any.”[180] Nevertheless, this is a very subjective standard. No matter the results of the EIS, the land exchange will occur and Resolution will receive title to the parcel within sixty days of the publication of the EIS.[181] Although the Act states that the EIS “shall be used as the basis for all decisions under Federal law related to the proposed mine…and any related major Federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the human environment” such actions are simply procedural. While most EISs are conducted prior to an agency formulating a decision and are actually used to determine agency action, this land exchange is a done deal. To think otherwise is simply to misunderstand how the EIS process under NEPA works.

The bottom line is that bills proposing the land exchange were introduced multiple times and only one of them passed on its merits. This rejection demonstrates the will of Congress, and at least theoretically, the will of the American people. However, a very small minority (read: Arizona Republicans) including the bill as a rider on a must-pass defense bill denigrates the legislative process. These individuals should not have circumvented the will of the majority of Congress to pass a potentially self-serving bill. Using a process similar to that used for administrative land exchanges has the potential to alleviate these problems.

Despite strong opinions and years of fighting over the issue, it will likely be more effective for the USFS and other affected parties to work with, as opposed to against, Resolution. Interestingly enough, two different climbing groups are on opposite sides of this debate. On the one hand, The Access Fund,[182] which seeks to protect rock-climbing areas throughout the nation, is vehemently opposed to the mine project, citing alternative mining methods that “‘would make money, but not as much money.’”[183] In particular, the Access Fund sees the Oak Flat’s listing in the National Register as an opportunity and an affirmation of the site’s importance.[184] Designation as an historic site makes denial that the site is important, at least to a subset of the Apache tribe, “harder to do.”[185] On the other hand, Queen Creek Coalition (“QCC”), a non-profit climbing organization in the Superior area, has expressed its support for the project and is attempting to maintain as much access to the land as possible by coordinating and cooperating with Resolution. Much of the best climbing in the area is located on private land owned by Resolution, so climbers are already subject to the company’s beneficence.[186] Climbing areas are also located on Arizona State Trust land and on Tonto National Forest land.[187] QCC’s work with Resolution included the establishment of a Recreational Use License in July 2012,[188] which will allow continued access to climbing areas on the land after Resolution attains ownership, essentially amounting to a waiver of liability by climbers wishing to use the area.[189] Although Resolution and QCC ultimately decided to keep the details of the licensing agreement proprietary, the license allows for climbing on Resolution’s private land for initial terms of one or five years, with renewals of additional one- or five-year terms. In exchange for the support of the community, Resolution will provide QCC with monetary compensation for the development of rock climbing areas outside of the immediate mining zone.[190] Therefore, although there is no provision in the final passed Act requiring Resolution to establish alternative rock climbing areas, QCC has managed to ensure that will occur. Despite their differences, or perhaps as a result of them, QCC’s collaboration with Resolution has created an enormous triumph for the climbing community.

Paul Diefenderfer, chairman of QCC, maintains a realistic attitude regarding the project:

I know a lot of people don’t agree with how the bill was passed. But when you look at the amount of money in the ground there, there was just no way it is going to be left in there. If this was the Grand Canyon, it would be different. But it’s a mining area. Unfortunately, there happens to be some really cool rocks on top of it.[191]

In addition to working with Resolution, QCC has also begun partnerships with various trail, recreation, and mountain biking groups to coordinate plans for increased recreational opportunities in the area despite the presence of the Resolution Copper mine.[192] QCC hopes to create a recreational greenbelt around the mine, a vision Resolution says it supports, both ideologically and financially.[193] Recreation and mining do not have to be mutually exclusive, a point that QCC stresses.[194] The key will be to capitalize on the opportunities this situation creates, something QCC and other organizations are doing quite successfully. It is unlikely that individuals will be able to beat a multi-billion dollar company like Resolution into submission. However, organizations like QCC are also not simply bowing down to inevitable development. The agreement between QCC and Resolution ultimately creates a mutually beneficial arrangement. QCC retains access to many climbing areas and Resolution receives less backlash and resistance from an important community group.

Public land should be made available for the use and enjoyment of the public. Resolution argues that, because mining often destroys the public use value of land due of the safety hazards and access issues associated with mining, it makes more sense for mined land to be transferred to private ownership in exchange for equally valuable land.[195] The Forest Service motto is “Land of Many Uses” and Forest Service land supports grazing, timber harvesting, recreation, and mining. But following from that motto and borrowing from Forest Service regulations, if the “best use of the property”[196] truly is mining, then Resolution’s argument makes sense. Why not make use of such value?

It is unlikely that visitorship to the area will diminish in the coming years—if anything, tourism and outdoor recreational activities have been increasing recently. Recreation generates approximately $10.6 billion to the Arizona economy each year.[197] And it is unlikely that the presence of a copper mine will discourage visitors from the area—if anything people will want to visit the area before it is affected by the mine. Although it may take some time to transfer Resolution’s lands fully into USFS and BLM management, these areas will open up new recreational and economic opportunities for the state.

While the upcoming land exchange with Resolution is unavoidable, barring miraculous bipartisanship in Congress, these events have created a learning opportunity for future legislative land exchanges. They have also created an opportunity for a powerful company to demonstrate that it can cooperate and collaborate with some concerned citizen groups. The environmental issues and economic debates in this case are not clear-cut. Despite the environmental impacts of copper mining, it is vital for the Arizona and national economy. In 2011, copper mining in Arizona employed 10,637 workers[198] and paid $212 million in state and local taxes.[199] However, there is clearly room for improvement in this process. More government-to-government consultation is needed between the federal government and the tribes. This includes, especially, pre-exchange consultation. More public input should be allowed, increasing transparency throughout the process. For future land exchanges involving mineral deposits, the exchange should require royalty payments, in contrast to the lack of such requirement under the 1872 Mining Law. At least a portion of the minerals extracted from mines located on formerly federal land should be processed and sold within the United States. The exchange of federal property needs to ultimately benefit the nation as a whole.

Unfortunately, it is controversial land exchanges like this that garner the majority of the public’s attention. However, it is important to remember that land exchanges, both administrative and legislative, remain an extremely valuable tool for the acquisition of land by the federal government. But all land exchanges must be governed by the public interest and follow a strict procedure to maintain that standard. This applies whether that public interest is in mineral rights, cultural or recreational values, or the protection of wildlife. There is still much to be learned and gained from this process.

- *J.D. Candidate, University of Colorado Law School. ↑

- Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness 331 (1986). ↑

- This law is discussed in Part II of this note. Under the 1872 Mining Law, more than 65,000 mining patents conveyed over 3.2 million acres of federal land to private ownership. U.S. Gen. Accounting Office, GAO/RCED-89-72, Federal Land Management: The Mining Law of 1872 Needs Revision 2, 10 (1989), http://archive.gao.gov/d15t6/13 8159.pdf. ↑

- Paul W. Gates, History of Public Land Law Development 384-85 (1968). ↑

- Raleigh Barlowe et al., Land Disposal Techniques and Procedures: A Study Prepared for the Public Land Law Review Commission 141 (1970). ↑

- U.S. Forest Serv., Oak Flat, Tonto National Forest, http://www.fs.usda.gov/ recarea/tonto/recarea/?recid=35345 (last visited Mar. 12, 2016); Bob Young, Copper Mining and the Fight for Oak Flat, AZ Central, http://www.azcentr al.com/story/travel/2015/07/10/oak-flat-land-swap-future-area/29958947/ (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- Ariz. Riparian Council, Arizona Riparian Council Fact Sheet, Arizona Riparian Council 2-3, https://azriparian.org/docs/arc/factsheets/Fact1.pdf (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- Sky Jacobs & Aaron Flesch, Vegetation and Wildlife Survey of Devil’s Canyon, Tonto National Forest (May 2009) 5, http://www.mining-law-reform.info/devils-canyon-survey.pdf (last visited Mar. 12, 2016); Common Black-Hawk, Arizona Game and Fish Department Heritage Data Management System, http://www.azgfd.gov/w_c/edits/ documents/Buteanth.d.pdf (last visited Mar. 12, 2016); American Peregrine Falcon, Arizona Game and Fish Department Heritage Data Management System, http://www.gf.state.az.us/w_c/edits/documents/Falcpean.fi_004.pdf (last visited Mar. 12, 2016).

Wildlife of Special Concern species in Arizona are often listed as such due to known or potential population declines, often as a result of significant habitat loss or the threat of habitat loss. Taxa listed as Wildlife of Special Concern may or may not also be listed as federally endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Status Definitions, Arizona Game and Fish Department, http://ag.arizona.edu/cochise/mws/SandsRanch CRM/Status_definitions_new.doc (last visited Mar. 12, 2016); Arizona Game and Fish Department, Wildlife of Special Concern in Arizona (Mar. 16, 1996), http://www.azgfd.gov/pdfs/w_c/heritage/heritage_special_concern.pdf. ↑

- Queen Creek Boulder Comp, http://www.queencreekbouldercomp.com/ (last visited Mar. 12, 2016); Ray Stern, A Copper Mine Near Superior and Oak Flat Campground is Set to Destroy a Unique, Sacred Recreation Area – For Fleeting Benefits, Phoenix New Times, http://www.phoenixnewtimes.com/news/a-copper-mine-near-superi or-and-oak-flat-campground-is-set-to-destroy-a-unique-sacred-recreation-area-for-fleeting-benefits-7287269 (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- Queen Creek Coalition, Who We Are, History of the QCC, http://theqcc.com/ main/qcc_news_history.html (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- Lee Allen, Hundreds Gather at Oak Flat to Fight for Sacred Apache Land, Indian Country Today Media Network (Feb. 9, 2015), http://indiancountrytodaymedianet work.com/2015/02/09/hundreds-gather-oak-flat-fight-sacred-apache-land-159119; Jack Jenkins, Citing Religious Freedom, Native Americans Fight to Take Back Sacred Land from Mining Companies, Think Progress (Jul. 24, 2016, 8:00 AM), http://thinkprogress. org/climate/2015/07/24/3683935/citing-religious-freedom-native-americans-fight-take-back-sacred-land-mining-companies/. ↑

- Zach Zorich, Planned Arizona Copper Mine Would Put a Hole in Apache Archaeology, Science (Dec. 10, 2014, 3:00 PM), http://www.sciencemag.org/news/ 2014/12/planned-arizona-copper-mine-would-put-hole-apache-archaeology. ↑

- U.S. Forest Serv., History and Development, Tonto National Forest, http:// www.fs.usda.gov/detail/tonto/home/?cid=fsbdev3_018924 (last visited Mar. 12, 2016); U.S. Forest Serv., Welcome to Tonto National Forest, Tonto National Forest, http:// www.fs.usda.gov/tonto (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- U.S. Forest Serv., supra note 12. ↑

- U.S. Forest Serv., Facts & Statistics, Tonto National Forest (May 3, 2006), http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/tonto/about-forest/?cid=fsbdev3_018930. ↑

- U.S. Forest Serv., Recreation, Tonto National Forest, http://www.fs.usda. gov/recmain/tonto/recreation (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- U.S. Forest Serv., supra note 12. ↑

- A Boom Too Far?, The Economist (Apr. 14, 2012), http://www.economist.com/ node/21552595. ↑

- Resolution Copper Mining, 1870, About Us, http://resolutioncopper.com/ about-us/#1 (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- Id. ↑

- When copper is mined, the ore is often only low-grade and therefore contains varying amounts of dirt, clay, and other minerals. These minerals must be removed from the pure copper. This is done by grinding the unrefined copper ore and then adding water to form a slurry. The ore-water slurry is then processed through a method called floatation, which allows the copper to float to the surface of the slurry and be recovered. The waste material of this process is known as the tailings. Chris Cavette, Copper, How Products Are Made, http://www.madehow.com/Volume-4/Copper.html (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- David F. Briggs, History of the Magma Mine, Superior, Arizona, Arizona Daily Independent (Jul. 19, 2015), https://arizonadailyindependent.com/2015/07/19/history-of-the-magma-mine-superior-arizona/. ↑

- See id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- General Mining Law of 1872, 17 Stat. 91 (1872) (codified as amended in scattered sections of 30 U.S.C.). ↑

- David Briggs, Myths and Facts About Mining Reform, Arizona Daily Independent (Aug. 25, 2015), https://arizonadailyindependent.com/2015/08/25/myths-and-facts-about-mining-reform/. ↑

- See Scott K. Miller, Missing the Forest and the Trees: Lost Opportunities for Federal Land Exchanges, 38 Colum. J. Envtl. L. 197, 206, 207-11 (2013). ↑

- 30 U.S.C. § 22 (2012). ↑

- Id. §23. ↑

- E.g., 30 C.F.R. § 1202.100 (2013). ↑

- Resolution Copper Mining, Summary – The 1872 Mining Law & H.R. 687 and S.B. 339, Resolution Copper Mining (Mar. 7, 2013), http://resolutioncopper.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/1872-Mining-Law-Summary.pdf. ↑

- 30 U.S.C. § 28f(a)(1). ↑

- This is for claims made after May 10, 1872. For claims made prior to May 10, 1872, the claimant must perform only $10 worth of labor or improvements each year. See 30 U.S.C. § 28. ↑

- 30 U.S.C. 28f(d)(1). ↑

- Id. §29. ↑

- Bureau of Land Mgmt., Mineral Patents, Mining & Minerals (Aug. 7, 2013),

http://www.blm.gov/ca/st/en/prog/minerals/patents.html. ↑

- Bureau of Land Mgmt., supra note 35; U.S. Forest Service, Mining in National Forests, U.S. Forest Serv., http://www.fs.fed.us/geology/1975_mining%20in%20nation al%20forests.pdf (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- The Department of the Interior oversees the Bureau of Land Management; the U.S. Department of Agriculture oversees the U.S. Forest Service. ↑

- See generally Carol Hardy Vincent et al., Federal Land Ownership: Acquisition and Disposal Authorities (May 19, 2015), https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/ misc/RL34273.pdf (citing various authorities under which the BLM and USFS may conduct land exchanges). ↑

- U.S. Forest Serv., A Guide to Land Exchanges on National Forest Lands, U.S. Forest Service, http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/fsbdev3_034082. pdf (last visited Mar. 12, 2016) [hereinafter Forest Service Land Exchange Guide]. ↑

- Bureau of Land Mgmt., Exchange, Lands and Realty (Mar. 29, 2011),

http://www.blm.gov/wo/st/en/prog/more/lands/land_tenure/exchange.html. ↑

- See Forest Service Land Exchange Guide, supra note 39. ↑

- Miller, supra note 26, at 206 (explaining that the BLM and USFS oversee 69% of federal land exchanges) (citations omitted). ↑

- 43 U.S.C. § 1716(a) (2012). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Center for Biological Diversity v. U.S. Dept. of Interior, 623 F.3d 633, 641 (9th Cir. 2010). ↑

- 43 U.S.C. § 1716(a). ↑

- National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, Pub. L. 91-190, 83 Stat. 852 (1970) (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. §§ 4321-4370 (2012)). ↑

- National Environmental Policy Act § 102(2)(C)(i)-(iii) (codified as 42 U.S.C. § 4331(2)(C)(i)-(iii)). ↑

- Robertson v. Methow Valley Citizens Council, 490 U.S. 332, 351 (1989). ↑

- Id. at 350. ↑

- See 42 U.S.C. § 4332. ↑

- U.S. Const. art. IV, §3, cl. 2. ↑

- Kleppe v. New Mexico, 426 U.S. 529, 536 (1976). ↑

- This is language for withdrawals under FLPMA, 43 U.S.C. § 1702(h). The withdrawal under PLO 1229 occurred before FLPMA was enacted, but the rationale was the same. ↑

- Legislative Hearing on H.R. 3301, to Authorize and Direct the Exchange and Conveyance of Certain National Forest Land and Other Land in Southeast Arizona (Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act of 2007) Before the Subcomm. on Nat’l Parks, Forests, and Pub. Lands, 110th Cong. 9 (2007) (statement of Joel Holtrop, Deputy Chief, National Forest System). ↑

- 20 Fed. Reg. 7319, 7336-37 (Oct. 1, 1955). ↑

- 36 Fed. Reg. 18997, 19029 (Sept. 25, 1971). ↑

- David F. Briggs, Resolution Copper – Setting the Record Straight About Oak Flat, Arizona Daily Independent (Jun. 9, 2015), https://arizonadailyindependent.com/2015/ 06/09/resolution-copper-setting-the-record-straight-about-oak-flat/; Stern, supra note 8. ↑

- Resolution Copper Mining, About Us, Resolution Copper Mining, http:// resolutioncopper.com/about-us/. (last visited Mar. 12, 2016); BHP Billiton, Our Structure, About Us, http://www.bhpbilliton.com/aboutus/ourcompany/ourStructure (last visited Mar. 12, 2016); Rio Tinto, About Rio Tinto, About Us, http://www. riotinto.com/aboutus/about-rio-tinto-5004.aspx (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- About Us, supra note 59; Briggs, supra note 21. ↑

- About Us, supra note 59. ↑

- Resolution Copper Mining, Resolution Copper – Project Summary, Resolution Copper Mining (Mar. 15, 2013), http://resolutioncopper.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/ 04/Project-Summary.pdf. ↑

- About Us, supra note 59. ↑

- Resolution Copper Mining, Underground Mining, The Project, http://resolutioncopper.com/the-project/underground-mining/ (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- Open pit mining is a type of surface mining that does not involve the use of tunnels to extract the desired mineral. This method creates enormous amounts of waste because all the rock and earth that contains the ore must be removed and placed elsewhere. Open pit mining also leaves a large open pit after the mining is complete. (see Resolution Copper Mining, Managing subsidence, visual impact and the mining footprint, Environment, http://resolutioncopper.com/sdr/2011/environment (last visited Mar. 12, 2016); Resolution Copper Mining, General Plan of Operations Volume 1 Environmental Setting and Project Description (November 2013) 13, http://resolutioncopper.com/the-project/ mine-plan-of-operations/ [hereinafter GPO]. ↑

- GPO, supra note 65, at 108-09; Stern, supra note 8. ↑

- Resolution Copper Mining, Mining Approach, Environment, http://resolutioncopper.com/sdr/2011/environment (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- Underground Mining, supra note 64. ↑

- Mining Approach, supra note 67. ↑

- Summary, supra note 30. ↑

- GPO, supra note 65, at 19 (figure as of 2013). ↑

- 36 Fed. Reg. 18997, 19029 (Sept. 25, 1971). ↑

- Lee Allison, Copper could act on Resolution copper land deal in omnibus deal, Arizona Geology (Dec. 8, 2010), http://arizonageology.blogspot.com/2010/12/congress-could-act-on-resolution-copper.html. ↑

- H.R.2618, 109th Cong. § 4(a), (c) (2005); S.1122, 109th Cong. §4(a), (c) (2005). ↑

- H.R.2618; S.1122. ↑

- Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act of 2011 (H.R. 1904), Committee Legislation, http://naturalresources.house.gov/legislation/?legislationid=26 8866 (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- U.S. Const. art. IV, §3. ↑

- Constitutional Authority Statement, H.R. 687, 113th Cong. (2013). ↑

- 426 U.S. 529, 542-543 (1976). ↑

- Constitutional Authority Statement, H.R. 687. ↑

- S. 339, 113th Cong. (2013). ↑

- H.R. 687, 113th Cong. § 2(a)(1) (2013); S. 339, 113th Cong. §2(a)(1) (2013). ↑

- H.R. 687; S. 339. ↑

- A rider is a provision included in a larger unrelated bill. ↑

- Pub. L. No. 113-291, 128 Stat. 3282 (2014). The Act was included as § 3003 of the NDAA, to be codified as 15 U.S.C. §539p. ↑

- Must-pass legislation includes bills that are considered vitally important and time-sensitive, such as those relating to the federal budget or national defense. ↑

- H.R. 3979, 113th Cong. (2014) (enacted). ↑

- H.R. 3979; Resolution Copper Mining, Land Exchange & Conservation, Land Exchange, http://resolutioncopper.com/land-exchange/ (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- NDAA § 3003(c)(4)(A), 36 C.F.R. § 254.9(a)(1) (2015). ↑

- 36 C.F.R. §254.9(b)(1)(i) (emphasis added). ↑

- NDAA § 3003(c)(4)(B)(iv). ↑

- Land Exchange & Conservation, supra note 88. ↑

- Resolution Copper Mining, 2004, About Us, http://resolutioncopper.com/about-us/#18 (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- Resolution Copper Mining, Land Parcel Fact Sheet, Land Exchange, http://resolutioncopper.com/land-exchange/ (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- Land Parcel Fact Sheet, supra note 94. ↑

- H.R.2618, 109th Cong. § 5(b)(2) (2005). ↑

- NDAA § 3003(c)(5)(C). ↑

- H.R.2618, 109th Cong. § 6(a)-(c). ↑

- The Nature Conservancy, Conservation Easements, Private Lands Conservation, http://www.nature.org/about-us/private-lands-conservation/conservation-easements/what-are-conservation-easements.xml (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- NDAA § 3003(d)(1)(A)(v). ↑

- Id. § (f). ↑

- Apache Leap Special Management Area, U.S. Forest Service, http://www.apacheleapsma.us/ (last visited Mar. 23, 2017) [hereinafter Apache Leap SMA]. ↑

- Id. § (g)(2)(A)-(C) ↑

- Id. § (f)(1)-(3) ↑

- GPO, supra note 65, at 109. ↑

- Apache Leap SMA, supra note 102. ↑

- Conservation Easements, supra note 99. ↑

- H.R.2618, 109th Cong. § 8(a) (2005); S.R. 1122, 109th Cong. § 8(a) (2005). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. § 8(b). ↑

- H.R. 4880, 111th Cong. § 5(a) (2010). ↑

- NDAA § 3003(i)((3). ↑

- Statement of Mary Wagner, Associate Chief, U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Forest Service (Mar. 21, 2013), http://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/media/types/testimony/ USDA_HNRC_03-21-2013_Testimony_Final.pdf. ↑

- Executive Order 13175, signed by President Bill Clinton in 2000, called for agencies to engage in “regular and meaningful consultation and collaboration with tribal officials in the development of Federal policies that have tribal implications.” E.O. 13175 (Consultation and Coordination with Indian Tribal Governments), 65 Fed. Reg. 67249, 67249 (Nov. 9, 2000). President Obama reiterated that sentiment and policy in 2009 in his Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies, requiring each agency to submit a plan detailing how it will implement Executive Order 13175. ↑

- Statement of Mary Wagner, supra note 113. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- H.R. Rep. No. 112-246, at 24 (2011) (dissenting views). ↑

- Resolution Copper Mining, Water, Environment, http://resolutioncopper.com/ environment/water/ (last visited Mar. 18, 2017). ↑

- GPO, supra note 65, at 21. ↑

- Water, supra note 119. The CAP system diverts approximately 1.5 million acre-feet of water each year from Lake Havasu to central and southern Arizona through a series of aqueducts, tunnels, pumping plants, and pipelines. Central Arizona Project, http://www.cap-az.com/ (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- GPO, supra note 65, at 21. Water is treated at an on-site water treatment plant. Resolution Copper Mining, Water, Project Facts 2, http://49ghjw30ttw221aqro12vwhmu6s.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/project_landing_page_fact.pdf (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). The dewatering process involves removing standing water that has accumulated in the mine, both by natural processes from ground and surface water, and a result of the mining itself. Resolution Copper Mining, Water, Project Facts 2, http://49ghjw30ttw221aqro12vwhmu6s.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/project_landing_page_fact.pdf (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- Resolution Copper Mining, Water, Project Facts 2, http://49ghjw30ttw221aqro12vwhmu6s.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/ 2012/08/project_landing_page_fact.pdf (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- Id. ↑

- H.R.2811, 114th Cong. (2015). ↑

- S.2242, 114th Cong. (2015). ↑

- H.R.2811, § 2(4) S. 2242, § 2(4). ↑

- H.R.2811, § 3; S. 2242, § 3. ↑

- H.R. 2811; S.2242. ↑

- Oak Flat, National Trust for Historic Preservation, https://savingplaces.org/places/oak-flat#.WM6w3xIrKAw (last visited Mar. 23, 2017). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Chi’chil Bildagoteel is the traditional name for the Oak Flat area. ↑

- 81 Fed. Reg. 3469, 3469 (Jan. 21, 2016). The U.S. Forest Service, in consultation with the San Carlos Apache tribe, nominated the Oak Flat area, as authorized by 36 C.F.R. § 60.9(a). ↑

- Rep. Gosar Rips Bogus Historic Site Listing which Threatens Arizona Jobs, Economic Growth, Congressman Paul Gosar (Mar. 7, 2016), http://gosar.house.gov/press-release/rep-gosar-rips-bogus-historic-site-listing-which-threatens-arizona-jobs-economic [hereinafter Gosar]. Representative Gosar argued that by using the area’s traditional name, members of the public were unable to adequately respond to the nomination. He also claimed that the comment period was insufficient. However, NPS abided by the originally required 15-day public comment period, 36 C.F.R. § 60.13(a) (2015), and even extended the comment period when requested, 81 Fed. Reg. 10276 (Feb 29, 2016). ↑

- Gosar, supra note 134; Emily Bregel, Historic designation of mining site provokes lawmakers’ anger, Tucson.com (Mar. 14, 2016), http://tucson.com/news/historic-designation-of-mining-site-provokes-lawmakers-anger/article_42b65dcd-6b5c-5355-8a50-150ae8a65a48.html [hereinafter Bregel]. ↑

- Bregel, supra note 135. ↑

- Letter from Stephanie S. Toothman, Ph.D., Keeper of the National Register of Historic Places, to Representative Paul A. Gosar (Feb. 5, 2016), https://www.scribd.com/doc/301305346/Oak-Flat-response-from-NPS. Dr. Toothman also addressed in her letter Representative Gosar’s contention that the nomination review period was troublingly short. 36 C.F.R. §§ 60.6(t), 60.12(a) allow a maximum comment period extension of 30 days. Representative Gosar sent his request for withdrawal of the nomination (which is not in the Keeper’s power) on February 1, 2016; Dr. Toothman responded on February 5, 2016. The NPS thereafter extended the comment period to March 4, 2016. 81 Fed. Reg. 10276. ↑

- National Register of Historic Places Program: Weekly List (March 11, 2016), National Register of Historic Places, https://www.nps.gov/nr/listings/20160311.htm. ↑

- Kari Lydersen, Despite Promised Jobs, Desert Town Opposes Giant Copper Mine, In These Times (Jun. 11, 2014, 11:23 AM), http://inthesetimes.com/working/ entry/16816/mining_no_longer_superior_for_small_arizona_town. ↑

- 36 C.F.R. § 60.2(a); National Historic Preservation Act, Pub. L. 89-665, as amended by Pub. L. 96-515, codified at 54 U.S.C. §§ 300101 et seq. (2014). ↑

- 36 C.F.R. § 60.2(a). ↑

- Bregel, supra note 135. ↑

- Sierra Club, Additional Guiding Principles, Public Land Exchange, http://www.sierraclub.org/policy/public-land-exchange (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- See Miller, supra note 26, at 199. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Bureau of Land Mgmt., supra note 39; U.S. Forest Serv., supra note 38. ↑

- Miller, supra note 26, at 218. ↑

- Lydia Millet, Selling Off Apache Holy Land, N.Y. Times (May 29, 2015), http:// www.nytimes.com/2015/05/29/opinion/selling-off-apache-holy-land.html. ↑

- John McCain, Statement by Senator John McCain on Protest of Resolution Copper Land Exchange in Washington, D.C. Today, Press Releases (Jul. 22, 2015), http://www.mccain.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2015/7/statement-by-senator-john-mccain-on-protest-of-resolution-copper-land-exchange-in-washington-d-c-today. ↑

- U.S. Forest Serv., Order 12-12-022 Oak Flat Campground Special Event Closure Tonto National Forest May 12 thru May 22, 2012, Tonto National Forest (May 11, 2012), http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5368136.pdf; U.S. Forest Serv., Order 12-14-059R Oak Flat Campground Special Event Closure for Traditional Cultural Use by the San Carlos Apache Tribe, Tonto National Forest (Oct. 1, 2014), http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprd3819135.pdf. ↑

- GPO, supra note 65, at 18. ↑

- Resolution Copper Mining, What is the “land exchange?”, Frequently Asked Questions, http://resolutioncopper.com/land-exchange/faq/ (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- U.S. Geological Survey, Copper Statistics and Information, Minerals Information (Feb. 23, 2016, 11:31 AM), http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/ commodity/copper/. ↑

- Id. ↑

- U.S. Geological Survey, Copper, Minerals Information, http://minerals. usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2016-coppe.pdf (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- Id. ↑

- U.S. Geological Survey, Estimate of Undiscovered Copper Resources of the World, 2013, Global Mineral Resource Assessment (Jan. 2014), http://pubs.usgs. gov/fs/2014/3004/pdf/fs2014-3004.pdf. ↑

- Mining Arizona, The Arizona Experience, http://arizonaexperience.org/land/ mining-arizona (last visited Mar. 12, 2016). ↑

- U.S. Forest Serv., Tonto National Forest Facts, Tonto National Forest (May 3, 2006), http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/tonto/about-forest/?cid=fsbdev3_018930. ↑