I. Introduction

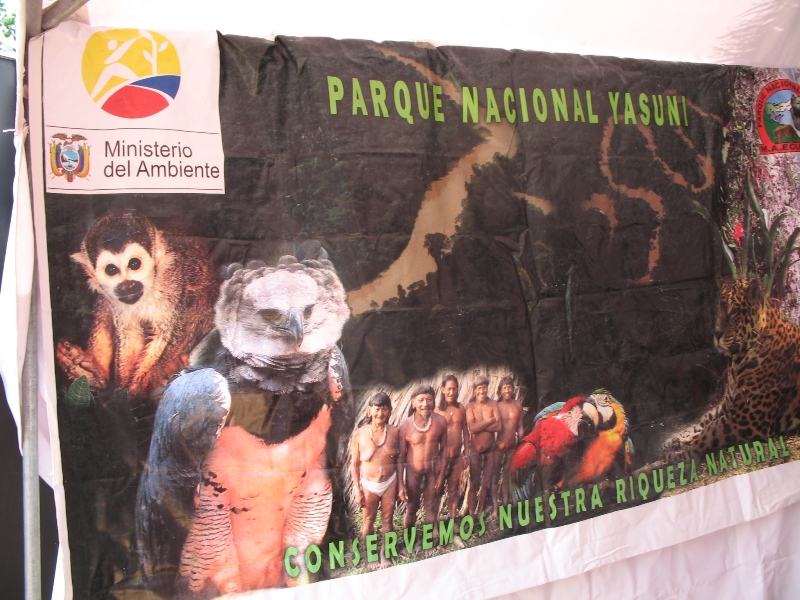

The Huaorani (Waorani) are hunters and gatherers who have lived in the Amazon Rainforest since before written history. Their ancestral lands span some 20,000 square kilometers and include the area now known as Yasuni National Park and Biosphere Reserve in the Republic of Ecuador. Yasuni is world-renowned for carbon rich forests and extraordinary biological diversity and is an important refuge for fresh water dolphins, harpy eagles, black caimans, and other threatened species and regional endemics. The Huaorani are legendary, even among other Indigenous peoples in Ecuador’s Amazon region, for their knowledge about the “giving”[2] rainforest and its plant and animal life. They are also renowned for their warriors, and long hardwood spears and blowguns.

In Ecuador, the Huaorani are also known as “Aucas,” a term that means “savages” and is considered deeply insulting by the Huaorani. Their name for themselves, Huaorani, means humanos (humans, or people). They refer to outsiders as cowode, which means desconocidos (strangers). For centuries, Huaorani warriors defended their territory from intrusions by cowode who sought to exploit the Amazon and conquer its inhabitants. They were the only known tribe in Ecuador to survive the rubber extraction boom—which ended around 1920—as “a free people.” In 1956, the Huaorani became world famous for spearing to death five North American evangelical missionaries from the U.S.-based Summer Institute of Linguistics and Wycliffe Bible Translators (“SIL/WBT”),[3] who were trying to make “contact” with them.[4] The first peaceful, sustained contacts between Huaorani and outsiders were in 1958, when SIL/WBT missionaries convinced Dayuma, a Huaorani woman who was living as a slave on a hacienda near Huaorani territory, to return to the forest where she had lived as a child and help the missionary-linguists relocate her relatives into a permanent settlement, teach them to live as Christians, and translate the Bible into their native tongue.[5]

In 1967, a consortium of foreign companies—wholly-owned subsidiaries of Texaco and Gulf, both now part of Chevron—struck oil in Ecuador’s Amazon region, near Huaorani territory. The discovery was heralded as the salvation of Ecuador’s economy, the product that would pull the nation out of chronic poverty and “underdevelopment” at last. At the time, the national economy was centered on the production and export of bananas.[6]

Oil exports began in 1972, after Texaco Petroleum, the operator of the consortium, completed construction of a 313-mile pipeline to transport crude oil out of the remote Amazon region across the Andes Mountains to the Pacific coast. The “first barrel” of Amazon Crude was paraded through the streets of the capital, Quito, like a hero. People could get drops of crude to commemorate the occasion and after the parade, the oil drum was placed on an alter-like structure at the Eloy Alfaro Military Academy.[7]

But the reality of oil development turned out to be far more complex than its triumphalist launch. For the Huaorani, the arrival of Texaco’s work crews meant destruction rather than progress. Their homelands were invaded and degraded by outsiders with unrelenting technological, military, and economic power. The first outsiders came from the sky; over time, they dramatically transformed natural and social environments. Their territory reduced and world changed forever, the Huaorani have borne the costs of oil development without sharing in its benefits or participating in a meaningful way in political and environmental decisions that affect them. Today, Huaorani who still live in their ancestral lands in Yasuni are organizing to defend their remaining lands, way of life, and self-determination. In addition to encroachments by oil companies and settlers, they face a new threat: conservation organizations and bureaucracies that seek to manage Yasuni and govern the Huaorani.

II. Oil Boom[8]

Texaco’s discovery of commercially valuable oil sparked an oil rush and petroleum quickly came to dominate Ecuador’s economy. The company named the first commercial field Lago Agrio, after an early Texaco gusher in Sour Lake, Texas; erected a one-thousand barrel per day refinery that had been prefabricated in the United States; and expanded exploration and production deeper into the rainforest.[9] Production rose to more than two-hundred thousand barrels per day by the end of 1973 and that same year, government income quadrupled.[10]

Initially, the oil boom stimulated nationalist sentiments in petroleum policy makers. The government claimed state ownership of oil resources, created a state oil company (Corporación Estatal Petrolera Ecuatoriana (“CEPE”), now Petroecuador), acquired ownership interests in the consortium that developed the fields, raised taxes, and demanded investments in infrastructure.

Before long, however, government officials learned that they have less power than commonly believed. Although relations between Ecuador and Texaco and other oil companies have not been static, at the core of those relationships lies an enduring political reality. Since the oil boom began, successive governments have linked national development plans and economic policy with petroleum, and the health of the oil industry has become a central concern for the State. At the same time, because oil is a nonrenewable resource, levels of production—and revenues—cannot be sustained without ongoing operations to find and develop new reserves, activities that are capital intensive and technology driven. Oil development has accentuated Ecuador’s dependence on export markets and foreign investment, technology, and expertise rather than providing the answer to Ecuador’s development aspirations.

When confronted with the realities of governance and oil politics, governments in Ecuador have vacillated over the extent to which petroleum policy should accommodate the interests of foreign oil companies or be nationalistic in outlook. Alarm over forecasts of the depletion of productive reserves has become a recurring theme in petroleum politics, as have the twin policy goals of expanded reserves and renewed exploration, and the corollary need to reform laws and policies to make the nation more attractive to foreign investors. The focus on economic and national development issues has eclipsed environmental and human rights concerns. Even the more nationalistic and populist policy makers have prioritized the need to promote oil extraction, and generally endeavored to maximize the State’s share of revenues and participation in oil development, while disregarding environmental protection and the rights of the Huaorani and other affected Indigenous peoples.

The initial bonanza and easy money from Texaco’s early finds were relatively short-lived, and just five years after production began, “a flood of foreign borrowing” was needed to sustain economic growth.[11] Ecuador has been able to secure large loans for its size because of its oil reserves and has accumulated a staggering foreign debt. At the same time, the benefits of oil development have not been well distributed. Income inequality and the percentage of Ecuadorians living in poverty remains stubbornly high.

III. National Integration and Land Rights

When the oil rush began, Ecuador’s institutions had very little influence in the Amazon. The Huaorani who lived in the areas where Texaco wanted to operate were free and sovereign, living in voluntary isolation in the forest. The discovery of black gold made the conquest of Amazonia, and pacification of the Huaorani, a national imperative. It also provided infrastructure to penetrate remote, previously inaccessible areas and monies to support the military and bureaucracy. Ecuador launched a national integration policy to incorporate the Amazon region into the nation’s economy and assimilate its native peoples into the dominant national culture. Successive governments have viewed the Amazon as a frontier to be conquered, a source of wealth for the State, and an escape valve for land distribution pressures in the highland and coastal regions.

The government aggressively promoted internal colonization and offered land titles and easy credit to settlers who migrated to the Amazon, cleared the forest, and planted crops or pasture, even though most soils in the region are not well-suited to livestock or mono-crop production.[12] Government officials pledged to civilize the Huaorani and other Amazonian peoples.[13]

On a visit to the Amazon in 1972, Ecuador’s President, General Rodriguez Lara, rebuffed an appeal from a neighboring tribe for formal recognition of Indigenous peoples in the government’s new development policies and protection of their lands from settlers. The President General said that all Ecuadorians are “part Indian,” with the blood of the Inca, Atahualpa, and insisted that he, too, was “part Indian,” although he did not know where he had acquired his “Indian” blood. “There is no more Indian problem,” he proclaimed, “we all become white when we accept the goals of the national culture.”[14] Within ten days, the President’s declaration of national ethnic homogeneity was codified by executive decree in the National Law of Culture.[15] Despite that ideal of national culture, established by administrative decree, Ecuadorian society has continued to be multi-ethnic and multi-cultural, and both racism against Indigenous peoples and extremes of wealth and poverty persist.

Ecuadorian law incorporated the doctrine of terra nullius, a racist doctrine that was used by European colonial powers in the Age of Discovery to provide a legal justification for annexing territories that were inhabited by Indigenous peoples and asserting legal and political sovereignty over Indigenous peoples. The doctrine of terra nullius has been aptly described by Peter Russell as both “confused and confusing,”[16] but it has nonetheless had an enduring effect on the way Ecuador has defined its relationship with the Huaorani. Essentially, it is a legal fiction that treats lands that were claimed by discovering European states as uninhabited—and thus belonging to no one—despite the presence of Indigenous peoples. The doctrine denies property and political rights to indigenous peoples based on the racist presumption that even though they lived on the land at the time of colonization, they were “savages” who were incapable of exercising political sovereignty or owning their lands, and their political economies were so “underdeveloped” that their very existence as self-governing societies, in possession of their lands, could be denied.[17]

In conjunction with the Doctrine of Discovery—a related international legal construct that can be traced back more than five hundred years to papal documents authorizing “discovery” of non-Christian lands, and which states that a Christian monarch who locates, or discovers, non-Christian, “heathen” lands has the right to claim dominion over them[18]—the doctrine of terra nullius has served as a legal justification for violating the rights of the Huaorani. In a preliminary study of the Doctrine of Discovery for the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, then-forum member Tonya Gonnella Frichner identified two key elements of the doctrine: dehumanization and dominance. Frichner found that the institutionalization of the doctrine in law and policy at national and international levels “lies at the root of the violations of indigenous peoples’ human rights . . . and has resulted in State claims to and the mass appropriation of the lands, territories and resources of indigenous peoples.”[19] Although Frichner primarily examined the operation of the Doctrine of Discovery and related “framework of dominance”[20] in U.S. federal Indian law, her findings are consistent with the experience of the Huaorani in Ecuador. There, a European colonial power and successor nation state have similarly used the Doctrine of Discovery and legal fiction of terra nullius to assert both a supreme, overriding title to Huaorani lands, territory, and resources and a paramount right to subjugate and govern the Huaorani, and appropriated Huaorani lands for oil extraction without consent or compensation. That, in turn, has resulted in dispossession and new problems and challenges for the Huaorani.

This remarkable claim, that the Amazon region was “tierras baldías,” vacant, uncultivated wastelands which belonged to the State because they had no other owner, despite the presence of the Huaorani and other Indigenous populations, was the prevailing doctrine in domestic law when the oil boom began.[21] It was not until 1997 that Ecuador affirmed, in a submission to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights for a report on human rights in Ecuador, that “the processes of ‘directed colonization’ and the consideration of large tracts of the Amazon basin as ‘tierras baldias’ may be considered superseded.”[22] By then, oil extraction and internal colonization by settlers had displaced the Huaorani from many areas. Moreover, notwithstanding that policy change, the right of the Huaorani to own and control their remaining lands, territory, and resources has continued to be limited by laws and policies that control the characterization and granting of title and by laws and policies associated with development and conservation activities. The Doctrine of Discovery and framework of dominance continue to serve as the foundation of human rights violations in Ecuador and undermine the land and self-determination rights of the Huaorani.

For the Huaorani, Ecuador’s national integration policy meant that their ancestral lands were occupied and degraded by outsiders. As Texaco expanded its operations and advanced into Huaorani territory, Huaorani warriors tried to drive off the oil invaders with hardwood spears. In response, Ecuador, Texaco, and missionaries from the SIL/WBT collaborated to pacify the Huaorani and end their way of life. Using aircraft supplied by Texaco, SIL/WBT intensified and expanded its program to contact, settle, and convert the Huaorani. Missionaries cruised the skies searching for Huaorani homes, dropping “gifts” and calling out to people through radio transmitters hidden in baskets lowered from the air. It was during this period, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, that most Huaorani were “contacted” by cowode for the first time.[23]

More than 200 Huaorani were pressured and tricked into leaving their homes, and taken to live in a distant Christian settlement.[24] Other Huaorani, including many in the area now known as Yasuni, refused to be “tamed”[25] but were displaced from large areas of their traditional territory. At least one family group, the Tagaeri-Taromenane, has continued to resist contact with outsiders and lives in voluntary isolation in the forest. Rosemary Kingsland, a journalist who wrote about the evangelization of the Huaorani with the missionaries’ cooperation, described the mood of the time:

The northern [oil] strike was enormous. . . . Nothing would stop them from going in[to Huaorani territory] now and there was talk of using guns, bombs, flame-throwers. Most of the talk was wild, but the result would be the same: a war between the oil men and the Aucas; a handful of naked savages standing squarely in the middle of fields of black gold, blocking the progress of the machine age. If it was to be a question of no oil or no Aucas, there was only one answer.[26]

The Huaorani who went to live with the missionaries were told that Huaorani culture is sinful and savage and were pressured to change, become “civilized,” and adopt the Christian way of life. Among other hardships, there were epidemics of new diseases (including a polio epidemic); important rainforest products were depleted; and the Huaorani, whose culture values personal autonomy, sharing and egalitarianism, had to rely on imported foods and medicines obtained by the missionaries. The new foods, medicines, and gifts of consumer items that the Huaorani could not themselves produce or obtain from their “giving” rainforest territory created relationships of dependency, inequality, and new needs for trading relationships with cowode.

Many elders recall the time “when the civilization arrived” as a period of great suffering, when new diseases sickened and killed many people. When some families returned to the land of their ancestors years later, it was not the same as before. The forest that was their home and source of life had been invaded and damaged by outsiders while they were away. In addition to wells, pipelines and production stations, Texaco built a 100-kilometer road into Huaorani territory—which it named “Via Auca” (Auca Road)—and settlers used the new road to colonize Huaorani lands.[27]

As a result of Texaco’s operations, the Huaorani lost their political sovereignty and sovereignty over their natural resources, and their territory, lands, and resources were significantly reduced. Many remaining lands and resources have been degraded, and pollution is a continuing problem and growing threat for a number of communities. These changes, in turn, have produced a host of new problems and challenges for the Huaorani, including the erosion of food security and self-reliance in meeting basic needs. Moreover, because Huaorani culture co-evolved with the Huaorani’s rainforest ecosystem, there is an inextricable relationship between Huaorani culture and the Huaorani’s ecosystem. As a result, the environmental injuries and displacement from ancestral lands have not only harmed the means of subsistence of the Huaorani, but also undermined their ability to conduct certain cultural practices and transmit their culture to future generations. As a group, the Huaorani have been thrust into a process of rapid change, external pressures, and loss of territory and access to natural resources that endangers their survival as a people. Texaco no longer operates in Ecuador, but its tragic legacy remains, and a growing number of other oil companies and settlers continue to push deeper into Huaorani lands.

The missionaries who worked with Texaco had their own converging interests. SIL/WBT described the “Aucas” as “murderers at heart” and its operation to convert them as “one of the most extraordinary missionary endeavors” of the twentieth century, “living proof of miracles brought to pass through God’s word.”[28] Nonetheless, the forced contact and relocation of the Huaorani was a systemic, ethnocidal public policy and campaign, promoted and aided by Ecuador and Texaco in order to open Huaorani territory to oil extraction and sever the Huaorani’s connection with their ancestral lands in areas where the company wanted to operate.[29] In addition to ignoring the basic human rights of the Huaorani, it was a form of discrimination that denied cultural, political, and property rights to them based on the prejudice of cultural superiority.[30] SIL/WBT was evidently aware of the convergence of interests; in “the ‘inside’ Auca story”[31] written by Ethel Emily Wallis, another missionary describes one of many helicopter operations supported by “the oil people” and comments on the expense:

This thing costs $200-300 an hour to run; and it was a three-hour operation—besides the four high-priced employees! The oil people, in turn, are more than willing to do what they can for our operation, since we have almost cleared their whole concession of Aucas. They assure us that they aren’t just being generous![32]

In 1969, Ecuador established a “Protectorate” for the Huaorani in the southwestern edge of their ancestral territory, which included the new Christian settlement, but only some 3.3 percent of Huaorani ancestral lands (66,578 hectares, or 665.78 square kilometers). In 1983, the area was titled to the Huaorani.[33] In 1990, a much larger area—6,125.6 square kilometers (subsequently increased to 6,137.5 square hectares)—was titled to the Huaorani, but with the provision that legal title could be revoked if the Huaorani “impede or obstruct” oil or mining activities.[34] In 2001, another 234.89 square kilometers was titled to the Organization of the Huaorani Nationality of the Ecuadorian Amazon (“ONHAE”).[35] The decision to award the land title to ONHAE instead of the Huaorani people is curious and was evidently made without the knowledge or consent of the grassroots Huaorani communities. Together, the titled lands are referred to (by cowode) as the Waorani Ethnic Reserve and include some 7,038 square kilometers, roughly one-third of traditional Huaorani territory. Other Huaorani lands have been titled to settlers and an even greater area—some 10,123 square kilometers—is located in Yasuni National Park and claimed as State land.[36] The Huaorani refer to the reserve, the park, and some adjacent lands as Huaorani territory, Ome.

In 1998, Ecuador formally recognized the multicultural nature of the country and some collective rights of Indigenous peoples when it ratified International Labour Organization Convention 169 and included Indigenous peoples’ rights in a new constitution. The constitutional rights echo provisions in the International Labour Organization Convention and include some recognition of collective land rights. [37] However, under Ecuadorian law, no land titles are truly secure because all subsurface minerals are claimed as property of the state, and oil extraction is permitted in lands that are titled to Indigenous peoples without their consent. Current law also claims state ownership of biodiversity and most protected natural areas, including Yasuni National Park.[38]

These restrictions on the rights of the Huaorani over their lands, territory and resources continue to be a major problem for communities in the Yasuni area, notwithstanding the proliferation of laws and policies at the national and international levels that recognize and guarantee rights of Indigenous peoples. Those developments include a new Constitution (adopted in 2008) that arguably strengthens the land and self-determination rights of Indigenous peoples in Ecuador, a new government that acknowledges that previous governments have violated the rights of Indigenous peoples and claims to be implementing transcendent changes, and a growing body of international norms and jurisprudence. The international law developments recognize that Indigenous peoples’ rights over their lands, territories, and resources are necessary for their survival, and include: the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted by the General Assembly in 2007;[39] a General Recommendation by the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (“CERD”), calling on States to recognize and protect the rights of Indigenous peoples, including rights over lands, territories, and resources, in accordance with the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination;[40] decisions and “concluding observations” by CERD in response to individual complaints and country reports, respectively;[41] and decisions and reports by the Inter-American Court and Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, respectively, interpreting and applying the right to property enshrined in the American Convention on Human Rights and American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man to protect the special relationship between Indigenous peoples and their territory, and recognizing rights of property over traditional lands and resources based on that relationship and customary norms.[42] The enormous gap between what some Huaorani call the “pretty words” in the law and the reality on the ground reflects the chasm between legal ideals and political realities, and the enduring legacy of the Doctrine of Discovery, framework of dominance, and legal fiction of terra nullius.

IV. Environmental Protection in the Oil Patch[43]

Oil exploration and production is an industrial activity. Among other impacts, it generates large quantities of wastes with toxic constituents and presents ongoing risks of spills. Ecuador’s Law of Hydrocarbons has included boilerplate environmental directives since at least 1971. Early provisions required oil field operators to “adopt necessary measures to protect the flora, fauna and other natural resources” and prevent contamination of water, air, and soil. Similarly, Texaco’s production contract with Ecuador, signed in 1973, required Texaco “to adopt suitable measures to protect flora, fauna, and other natural resources and to prevent contamination of water, air and soil under the control of pertinent organs of the state.” In theory, these and other comparable requirements in generally applicable laws, such as the 1972 Water Law, offer mechanisms for regulation of significant sources of oil field pollution. In practice, however, Texaco and other oil companies have ignored the laws, and successive governments have failed to implement and enforce them.

When Texaco began its operations, there was little public awareness or political interest in environmental issues. Environmental protection in the oil patch is expensive and requires a lot of work. Moreover, it depends on the use of technology, and Ecuador relied on Texaco as the operator of the first commercial fields to transfer hydrocarbon extraction technology. Ecuadorian officials saw Texaco as a prestigious international company with vast experience and access to “world class” technology and capital. They relied on Texaco to design, procure, install, and operate the infrastructure that turned Ecuador into an oil exporter. In its contract with the State, Texaco agreed to use “modern and efficient” equipment, train Ecuadorian students, and turn over the operations to Petroecuador when the contract ended in 1992.[44]

In the environmental law vacuum, Texaco set its own environmental standards and policed itself. As Petroecuador’s “professor,” Texaco also set standards for that company’s operations. Texaco’s standards and practices, however, did not include environmental protection. The company did not instruct its Ecuadorian personnel about environmental matters, and oil field workers who were trained by Texaco were so unaware of the hazards of crude oil during the 1970s and 1980s that they applied it to their heads to prevent balding. After applying the crude oil, they sat in the sun or covered their hair with plastic caps overnight. To remove the crude oil, they washed their hair with diesel. The rumors attributing medicinal qualities to Amazon crude are not entirely surprising, considering its status as the harbinger of a great future for the nation and Texaco’s neglect of environmental and human health concerns.

In 1990, when government officials were confronted with a study (subsequently published as Amazon Crude) by an environmental lawyer from the United States (the author) that documented shocking pollution and other impacts from operations by Texaco and other companies, they professed ignorance. Texaco was their “professor,” they explained; the company taught them how to produce oil, but did not teach environmental protection.[45]

That basic view, that public officials did not realize that industry operations were taking a serious toll on the environment until international environmentalists put a spotlight on the region, has been echoed by others. According to General Rene Vargas Pazzos, a key policy maker in the military government that ruled Ecuador when the oil rush began, government officials did not question Texaco about environmental practices because they did not question the company’s technical expertise or know that the operations could damage the environment:

We thought oil would generate a lot of money, and that development would benefit the country. But we did not have technical know-how, and no one told us that oil was bad for the environment . . . . We were fooled by Texaco. We were betrayed. We trusted the company . . . Texaco was responsible for all of the operations . . . . We were not experts . . . . The Hydrocarbons Directorate approved the work, but the technology came from Texaco. It is like contracting a doctor. You go in, and can see that the room is fine. But with the operation, it is beyond your control and know-how . . . .

We were happy about the petroleum. We said, “Do it, and tell us what it will cost” . . . But we did not know about environmental issues . . . . We thought Texaco used the best methods . . . . Texaco was the operator. We did not interfere in technical decisions because that was Texaco’s responsibility. That is what we paid them for…. We controlled only the production rates, the payment of taxes [and things like that]. . . .[46]

According to Vargas, all of the work plans and technical specifications for the operations were elaborated and approved by Texaco in the United States and sent to Quito from the company’s Latin America/West Africa Division, based in Coral Gables, Florida. According to Margarita Yepez, who worked for Texaco Petroleum from 1973-1989 and was based in Quito, the operations were closely supervised from the Coral Gables office: Every department head in Quito had a direct telephone line to a supervisor in Coral Gables; important contracts for field operations were approved and signed in the United States; expenditures were closely supervised from the United States; and the Quito office had a full-time employee to microfilm all reports and other written materials to send to Coral Gables in a daily mail pouch.

Texaco’s international prestige and day-to-day control as the operator of field activities, gave the company enormous power in the oil patch. That power can hardly be overestimated and was compounded by systemic deficiencies in the rule of law and good governance in Ecuador. Texaco’s power and the culture of impunity in the oil fields—the belief that companies can do whatever they want and suffer no adverse consequences as long as they get the oil—is illustrated in a remark by a worker in 1993, the year after Texaco’s contract expired. The man worked for a subcontractor, driving a truck that dumped untreated oil on roads for dust control and maintenance purposes. When asked what he thought about the practice, he replied: “Three years ago, I went to a training course . . . and a gringo from Texaco told us that oil nourishes the brain and retards aging. He said that in the United States they do this on all of the roads, and people there are very intelligent.” When asked if he believed what the trainer from Texaco had said, he answered: “It doesn’t matter what I think; here, Texaco, and now Petroecuador manda (gives the orders). Everyone works for them.”[47]

The consortium led by Texaco extracted nearly 1.5 billion barrels of Amazon crude over a period of twenty-eight years (1964-1992).[48] The operations expanded incrementally and by the time Texaco handed over operational responsibility to Petroecuador in 1990, it had drilled 339 wells in an area that spans roughly one million acres. The facilities were producing some 213,840 barrels of oil daily from more than 200 wells. They also generated more than 3.2 million gallons of toxic wastewater (oil field brine, also known as produced water) every day, virtually all of which was dumped into the environment via unlined, open-air earthen waste pits, without treatment or monitoring—a practice that has been generally banned in the United States by federal law since 1979. In addition, they generated more than 49 million cubic feet of natural gas every day. Some of the gas was processed for use in the operations; however, most was flared, or burned as a waste, without temperature or emissions controls, depleting a nonrenewable resource and contaminating the air with greenhouse gases, precursors of acid rain and ground level ozone, soot, and other contaminants.[49]

In addition to routine willful discharges and emissions, Texaco spilled nearly twice as much oil as the Exxon Valdez from the main pipeline alone, mostly in the Amazon basin.[50] Spills from secondary pipelines, flow lines, tanks, production stations, and other facilities were also frequent and continue to this day.[51] In contrast to the oil industry’s typically energetic response to spills in the United States, Texaco’s response in Ecuador was limited to shutting off the flow of petroleum into the damaged portion of the pipeline, and allowing the oil already in the line to spill into the environment before making the necessary repairs. No cleanup activities were undertaken and no assistance or compensation was provided to affected communities. Texaco’s pipeline system crosses myriad rivers and streams. As a result, depending on the location and size of the release, in addition to devastating local impacts, spills can cause oil slicks on waterways and foul water supplies and fisheries of downstream communities for scores or even hundreds of kilometers. Moreover, because spills are not properly cleaned up, they can become sources of ongoing chronic pollution in affected watersheds for months or years. The damages caused by Texaco are so serious and widespread that other oil companies now go to great lengths to try to distinguish their operations, and the following has become a common refrain: “We are not like Texaco, we use cutting edge technology and international standards to protect the environment.”

As oil extraction facilities age, they generate less oil and more produced water. They also require more costly maintenance to maximize production and prevent spills and other accidental releases. Basic oil field economics, then, do not favor environmental protection because the cost of protection typically increases as the income stream from facilities decreases. Petroecuador has continued to expand operations in the fields developed by Texaco; in addition, exploration and production by Petroecuador and other companies has expanded in new areas.

In the wake of Amazon Crude, environmental protection has become an important policy issue in Ecuador. Since the early 1990s, both government officials and oil companies must at least appear to be “green.” However, the implementation of environmentally significant changes in the field has lagged, despite both public pledges by a growing number of companies to voluntarily raise environmental standards, and a clear trend on paper toward increasingly detailed, albeit incomplete, environmental legal rights and requirements, including constitutional recognition since 1984 of the right of individuals to live in an environment “free from contamination,” expanded constitutional group environmental rights since 1998, and constitutional recognition of “rights of nature” since 2008. In addition to the legacy of Texaco, the implementation of environmental law in the oil fields has been hampered by the absence of political will, inadequate financing, lack of technical capacity, oil industry influence and resistance to regulation, corporate control of environmental decision-making, and the failure of the rule of law and good governance generally.[52]

V. Litigation in Texaco’s Homeland[53]

In 1993, a class action lawsuit was filed against Texaco in federal court in New York on behalf of Indigenous and settler residents who have been harmed by pollution from the company’s Ecuador operations. The suit, Aguinda v. Texaco, Inc., was filed by U.S.-based attorneys after an Ecuadorian-born lawyer, Cristobal Bonifaz, read about the Amazon Crude study.[54]

Class action law permits a group of named plaintiffs to sue as representatives of a plaintiff class, on behalf of a large group of similarly situated individuals. The complaint named some seventy-four plaintiffs, none of them Huaorani. The putative class was estimated to include at least 30,000 persons. The suit was based on common law claims of negligence, nuisance, trespass, civil conspiracy, and medical monitoring. It also included an international law claim, based on the Alien Tort Claims Act, and a claim for equitable relief to remedy the contamination. Until its merger with Chevron in 2001, Texaco’s corporate headquarters was in White Plains, New York, and the complaint alleged that decisions directing the harmful operations were made there.

The complaint did not identify all of the affected Indigenous groups or distinguish their claims and injuries from those of the settlers, known locally as “colonos” (colonists), who have also been adversely affected by the pollution and included among the named plaintiffs and putative class. Similarly, it did not include claims based on the specific rights of Indigenous peoples. However, in press releases and other public relations and advocacy activities related to the case, the plaintiffs’ lawyers and nongovernmental organizations (“NGOs”) that support the litigation often give the impression that all of the plaintiffs are Indigenous Amazonian peoples. As a result, confusion about the plaintiffs and origins of the litigation have characterized much of the extensive media reporting about the case, and it has commonly been described as a lawsuit brought by “Indians” or “indigenous people from the rainforest.”

In response to the lawsuit, Texaco denied any wrongdoing and vigorously fought the legal action. In submissions to the court and in the media, Texaco alleged that the operations had complied with Ecuadorian law and then-prevailing industry practices. Moreover, the company argued, its subsidiary (Texaco Petroleum) had not operated in Ecuador since 1990, and any legal claims should be pursued there instead of the United States. It touted the ability of Ecuadorian courts to provide a fair and alternative forum to administer justice.

In submissions to the court, Texaco also denied parent-company control over the operations.[55] This effort to distance the parent company from the Ecuador operations and assert that it had no role in environmental management there contradicted both the image that Texaco Petroleum had cultivated in Ecuador, of a leading international company based in the United States, and the image commonly promoted by Texaco in public relations materials and responses to concerned consumers and NGOs before it was sued, of an industry leader engaged in worldwide operations that is committed to environmentally responsible practices wherever it operates. Texaco’s legal submissions further contended that Petroecuador and Ecuador heavily regulated Texaco Petroleum’s environmental practices.

Outside court, Texaco and Ecuador moved quickly to negotiate issues raised by the lawsuit, in what ABC News Nightline later called an “exit agreement.”[56] They signed a series of agreements in 1994-1995. The agreements did not mention the Aguinda lawsuit, but purported to address how Texaco Petroleum would remedy the contamination at issue in the litigation.[57] Publicly, Texaco and Ecuador vowed that the company would clean up damaged areas and compensate affected communities.

Under the accord, Texaco agreed to implement limited environmental remediation work, make payments to Ecuador for socio-economic compensation projects, and negotiate contributions to public works with municipal governments of four boom towns that grew around the company’s operations and, in the wake of Aguinda v. Texaco, sued Texaco Petroleum in Ecuador.[58] In exchange, the government and Petroecuador agreed to release and liberate Texaco Petroleum and Texaco—and their subsidiaries and successors—from all claims, obligations, and liability to the Ecuadorian State and national oil company related to contamination from the operations. The agreements did not include a price tag, but Texaco subsequently reported that it spent $40 million on the remediation program.

The “remedial work” undertaken by the company, however, was limited in scope and largely cosmetic. It did not contain or reverse the tragic environmental legacy of the operations or benefit affected rural populations. Indeed, the accord—which was negotiated behind closed doors, without meaningful participation by affected communities, transparency, or other democratic safeguards—seemed more like an agreement between polluters to limit cleanup requirements and lower and divide their costs than a remediation program based on a credible assessment of environmental conditions and measures that are needed to remedy them. The final release of Texaco and its corporate family reflected the enduring political and economic power of the company and the selective application of the law in the oil frontier. Inasmuch as it liberates the company from environmental obligations to the State, it also raises serious questions of law and legitimacy.

In court, after nine years of litigation, Texaco’s efforts to dismiss the case were successful, and the Aguinda plaintiffs were essentially told to go home and sue in Ecuador. The lawsuit was dismissed on the ground of forum non conveniens, a doctrine that allows a court to dismiss a case that could be tried in a different court, in the interest of justice or for the convenience of the parties. Dismissal was conditioned on Texaco’s agreement to submit to the jurisdiction of Ecuador’s courts.[59]

When a federal court applies the forum non conveniens doctrine, it first determines whether there is an alternative forum and then balances private and public interest factors to determine which forum is more convenient. In Aguinda, the district court ruled that Ecuador’s courts provide an alternative forum, and that the balance of private and public interest factors “tips overwhelmingly in favor of dismissal.”[60] Despite the fact that Texaco’s headquarters was just a few miles from the courthouse where the case was filed, the judge, Jed Rakoff, concluded that the case has “everything to do with Ecuador and nothing to do with the United States.”[61]

Some of the facts used by the court to support its legal analysis were uncontested. For example, there were no allegations of injury in the United States; Texaco’s wholly-owned subsidiary built and operated the facilities; and after operations began, Ecuador acquired majority ownership of the assets and continued to operate them after Texaco Petroleum’s contract expired. Other facts, however, were in dispute. One area that was especially germane related to control of the operations. While not determinative of the legal questions by itself, the factual issue of where decisions were made about the technology and practices that caused the pollution, and who made them, was a material element of the analysis of both private and public interest factors, and clearly colored the decision to dismiss.

The proposition, advocated by Texaco and accepted by the Court, that Ecuadorians controlled the relevant decisions, that no one from Texaco or anyone else operating out of the United States made any material decisions or was involved in designing, directing, guiding, or assisting the activities that caused the pollution, and that environmental practices were heavily regulated by Ecuador, was a recurring theme. The Court also distinguished Texaco from Texaco Petroleum, the subsidiary that operated in Ecuador. That distinction, and the portrait of Texaco Petroleum as essentially an Ecuadorian company whose operations were far removed from the parent, was dramatically different from the image of “Texaco” in Ecuador and the impression there that the government had contracted with the U.S. company, Texaco. It was also at odds with the portrait cultivated by Texaco prior to the litigation, of a multinational industry leader that transferred world class technology to Ecuador. Altogether, the Aguinda court’s depiction of Texaco’s role in the operations was clearly incongruous with the reality of oil development in Ecuador, including the environmental law vacuum and culture of impunity in the oil frontier, the experience of Amazonian peoples and other Ecuadorians with the company, and the portrait that Texaco cultivated during its tenure in Ecuador.[62]

The Aguinda court’s determination that an adequate alternative forum exists was also colored by questionable factual assumptions, including erroneous and unsupported findings of fact about the history of litigation in Ecuador’s courts. For example, the court found that some plaintiffs had already “obtained tort judgments” against Texaco Petroleum and Petroecuador in Ecuadorian courts “on some of the very claims alleged” by the Aguinda plaintiffs,[63] a finding that was clearly erroneous.[64]

Another major finding, that the description of systemic shortcomings in Ecuador’s legal and judicial system by the U.S. Department of State in its Country Reports on human rights is largely limited to cases involving confrontations between political protestors and the police, was also erroneous and suggests a lack of candor by the court. Remarkably, the court misquoted the State Department report. Judge Rakoff evidently reviewed reports describing human rights practices during 1998 and 1999. Both reports state that “[t]he most fundamental human rights abuse [in Ecuador] stems from shortcomings in the politicized, inefficient, and corrupt legal and judicial system.”[65] However, the latter report was quoted by the court as “describ[ing] Ecuador’s legal and judicial systems as ‘politicized, inefficient and sometimes corrupt’ as far as certain ‘human rights’ practices are concerned.”[66] The misquotation was especially troubling because the same statement was quoted correctly by Judge Rakoff on two prior occasions and the litigation record suggested that the court allotted appreciable attention to considering its proper meaning.[67]

The Aguinda plaintiffs appealed to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. However, because forum non conveniens involves the exercise of discretion by the trial court, appellate courts have limited powers of review. In this case, the Second Circuit found no abuse of discretion.[68]

In its review of the district court judgment, the Second Circuit did not repeat all of the detailed factual rulings by Judge Rakoff, but it quoted his general finding that Aguinda “has everything to do with Ecuador and nothing to do with the United States” and apparently relied on at least some of the more specific findings to reject the plaintiffs’ appeal.[69] The Second Circuit also found it “significant” that Ecuador and Petroecuador could be joined in a lawsuit in Ecuador, but not in a U.S. forum, because they enjoy sovereign immunity here.[70] That factor was also cited by the district court and is related to Texaco’s contention that Ecuador and Petroecuador had primary control of the challenged operations[71] and, as a result, that it would be unfair for a lawsuit to proceed on the plaintiffs’ claims without Petroecuador. However, reliance on that factor now appears misplaced. Despite representations to the Aguinda court by Texaco that “Petroecuador can and will be brought into” the lawsuit if it is filed in Ecuador, that “[y]ou can’t try . . . [this case] without having Petroecuador present,” and that “[i]t just is almost a matter of fundamental fairness,”[72] ChevronTexaco (now Chevron)[73] did not seek to implead Petroecuador in the lawsuit filed in Ecuador by a group of Aguinda plaintiffs after their New York case was dismissed. Instead, as discussed below, ChevronTexaco and Texaco Petroleum filed an arbitration claim against Petroecuador with the American Arbitration Association in New York, seeking damages and indemnification of all fees, costs, and expenses relating to the litigation in Ecuador, including any adverse judgment that might be rendered in favor of the Aguinda plaintiffs there.[74]

After Aguinda v. Texaco was dismissed in favor of litigation in Ecuador, the plaintiffs’ lawyers filed a new lawsuit against ChevronTexaco (now Chevron) in Lago Agrio, the boom town that sprang up around Texaco’s first commercial field.[75] The complaint names forty-eight plaintiffs from two colonist and two Indigenous communities, and asserts claims on behalf of the Huaorani and other “Afectados,” local residents who have been harmed by the company’s operations. The Afectados include four Indigenous peoples (the Huaorani, Cofan, Secoya and Siona), members of the Kichwa people, and colonists.[76] However, the Huaorani were not consulted about the litigation or included among the plaintiffs, and no relief was requested directly for the affected communities (or community members) or even for the plaintiffs. Instead, the complaint seeks a judicial determination of the costs of a comprehensive environmental remediation and an order directing Chevron to pay the full amount to a local NGO, Amazon Defense Front (Frente de Defensa de la Amazonia), which would then “apply” the funds to the ends determined in the judgment. The complaint also claims a ten percent share of the remedial monies for the plaintiffs, but requests that those funds also be paid to Amazon Defense Front.[77]

Amazon Defense Front—known locally as “Frente”—was founded in 1994 by a group of colonists in Lago Agrio who heard about the Aguinda v. Texaco lawsuit on the radio and decided to establish a local institution to administer monies that they expected to be forthcoming from the case. The group has developed close ties with the plaintiffs’ lawyers and some external NGOs, but is controlled by colonists and is not regarded by the affected Indigenous peoples as their legitimate representative.[78] Moreover, its efforts to claim a monopoly of representation of all people affected by Texaco and mange local politics in an undemocratic fashion have alienated many people in the affected communities.[79] In addition to issues related to representation, another recurring concern involves possible remedies. Efforts by local residents, at different junctures over the years, to demand “clarity and transparency in the process,” obtain information from Frente and its lawyers, and engage them in a dialogue about remedial plans—in the event of a victory in court or out-of-court settlement—have been rebuffed.[80] The decision to designate Frente, which is not a plaintiff, as the trustee in charge of administering any judgment was evidently made by the plaintiffs’ lawyers and Frente without consulting or informing the affected communities.

In February 2011, the court in Lago Agrio ruled that Chevron is responsible for widespread pollution that has harmed, and continues to threaten, the environment, public health, and Indigenous cultures.[81] In a 188-page opinion, the court ordered Chevron to pay $8,646,160,000 for remedial measures,[82] and another $8,646,160,000 in punitive damages if the company did not publicly apologize to the affected communities within fifteen days.[83] The court also awarded an additional ten percent of the value of the “amount sentenced” to Frente.[84] Chevron has not apologized (and has publicly vowed not to apologize),[85] so the award to Frente is now worth $1.729232 billion[86] and the judgment totals more than $19 billion. The Lago Agrio judgment also directs the plaintiffs to set up a trust fund to administer the remedial monies, and provides that the sole beneficiary of the trust and its board of directors shall be Frente or the person or persons it designates.[87]

The purpose of the remedial measures is “to return things to their natural state” and restore natural resources and environmental conditions to the way they were before Chevron caused the damage that gave rise to the litigation. The court recognized, however, that it will be impossible to achieve that objective in many cases and, for that reason, included three types of remedies in the judgment:[88] “principal” measures to remediate contaminated soils and ground waters,[89] “complementary” measures to compensate for the inability to fully restore natural resources,[90] and “mitigation” measures to address the impacts on human health and Indigenous cultures that cannot be reversed or fully repaired.[91] The objective of the punitive damages is to compensate the affected communities for their pain and suffering, and punish Chevron for unreasonable and malicious conduct in the litigation which prolonged the suffering of the victims.[92]

Both the plaintiffs and Chevron appealed. The plaintiffs sought additional damages and Chevron sought to have the judgment reversed or declared null. In January 2012, the appellate (sole) division of the Lago Agrio court[93] affirmed the judgment in all material respects. The appellate division also ordered Chevron to pay an additional 0.1 percent of the value of the judgment as legal fees and directed the plaintiffs to establish a second trust fund to administer the punitive damages monies, to be managed by the same board of directors as the trust with the environmental remediation, compensation, and mitigation monies.[94]

Chevron appealed to Ecuador’s highest court, the National Court of Justice, and that appeal is pending. However, Chevron evidently does not expect to prevail in Ecuador’s courts—at least while the current President, Rafael Correa, is in power—and the company has limited assets in Ecuador.[95] Consequently, Chevron has been preparing to defend itself against possible enforcement actions in the United States and around the world by challenging the legitimacy of the judgment in two other fora: a lawsuit against the plaintiffs and their lawyers in federal court in New York, and an arbitration proceeding against Ecuador in The Hague. Both cases are based on allegations of fraud and other misconduct by the Lago Agrio plaintiffs’ legal team, allegations of improper collusion between representatives of the plaintiffs and Ecuadorian government officials, and allegations of systemic failures in the administration of justice in Ecuador.[96]

The proceeding in The Hague is the second arbitration claim pursued by Chevron to try to dodge liability to the Aguinda plaintiffs. The first arbitration claim, filed in New York in 2004, sought an order from an American Arbitration Association panel requiring Petroecuador to indemnify Chevron for all costs and liability related to the Lago Agrio litigation.[97] Ecuador and Petroecuador challenged the proceeding in a lawsuit in New York and in 2007, U.S. District Court Judge Leonard Sand stayed the arbitration on the ground that Ecuador was not contractually bound to arbitrate disputes with Chevron.[98]

The current arbitration began in 2009. Chevron’s notice of arbitration alleges that Ecuador violated a bilateral investment treaty with the United States (“BIT”)[99] by “permitting” the Lago Agrio litigation to proceed despite the settlement accord and remediation discussed above in Part V,[100] and by improperly colluding with the plaintiffs in that litigation and denying due process rights to Chevron. It seeks a declaration that Chevron has no liability or responsibility for the pollution that gave rise to the Aguinda litigation; a declaration that Ecuador or Petroecuador is exclusively liable for any judgment rendered in the Lago Agrio lawsuit; an order requiring Ecuador to inform the court in the Lago Agrio litigation that Chevron has been released from all liability for environmental impact and that Ecuador and Petroecuador are responsible for any remaining and future remediation work; indemnification from Ecuador for any costs, fees, or liability Chevron may incur as a result of the Lago Agrio lawsuit; an order requiring Ecuador to protect and defend Chevron in connection with that litigation; and moral damages to compensate Chevron for non-pecuniary harm.[101]

In support of its claims, Chevron maintains that the Lago Agrio plaintiffs’ claims for environmental remediation are barred by the releases granted by Ecuador pursuant to the remedial accord. Although the language in both the remediation agreement and final release from liability explicitly states that the releases apply to claims by Petroecuador and the Ecuadorian State[102]—and Ecuador maintains that it did not intend or agree to extinguish any rights or claims by third parties[103]—Chevron contends that the Lago Agrio plaintiffs had no right to sue for environmental remedies when the releases were granted, and only Ecuador could legally demand environmental remediation of the affected areas. Thus, the argument goes, the release of liability to Ecuador fully discharged Chevron from “any and all environmental liability,” and Ecuador and Petroecuador “retained responsibility for any remaining environmental impact and remediation work.”[104]

Despite the fact that the Aguinda v. Texaco lawsuit, which was pending when the release was negotiated, clearly sought both damages and equitable relief for environmental remediation,[105] Chevron now contends that Aguinda was “generally” an action for damages to individuals, unlike the Lago Agrio lawsuit which seeks to vindicate public rights to remediation.[106] The company further alleges that the right of private parties to sue in Ecuador to remedy generalized environmental injuries was first granted by a statute that was enacted in 1999 (after the final release) and that the Lago Agrio lawsuit is based on the improper retroactive application of that law.[107]

Chevron has also asserted that argument as a defense in the Lago Agrio litigation; however, the Lago Agrio court ruled that the law, the Environmental Management Act, is procedural in nature and does not confer new rights. As such, its application in the litigation does not violate the general rule against retroactive application of the law.[108] The substantive right of the plaintiffs to sue and seek redress for the harms that were alleged and adjudicated in the Lago Agrio lawsuit is established by provisions in Ecuador’s Civil Code that long pre-date the conduct and claims at issue in the case. Inspired by Roman law, the Napoleonic Code, and ancient Spanish civil codes (based primarily on Roman law), Ecuador’s Civil Code establishes generally applicable civil liability rights and obligations that include special causes of action, called “popular actions,” when activities threaten a large number of people with injury.[109] The Lago Agrio court further ruled that the release of liability granted to Chevron pursuant to the remedial accord applies only to claims by Ecuador and Petroecuador.[110]

Chevron, however, rejects the legitimacy of the Lago Agrio judgment. In its notice of arbitration, the company alleges that Ecuador “has engaged in a pattern of improper and fundamentally unfair conduct” that “breeches and effectively seeks to repudiate” the settlement accord and improperly assist and collude with the Lago Agrio plaintiffs and their lawyers, in an effort to shift the state’s environmental obligations to Chevron “through the Lago Agrio litigation” and “improperly influence the courts.”[111] In an effort to reconcile its current allegations with Texaco’s spirited defense of Ecuador’s legal and judicial system in the Aguinda v. Texaco litigation, Chevron further contends that the rule of law has deteriorated in Ecuador since the U.S. lawsuit was dismissed, and that in view of the current judicial reforms and public support expressed by the President Rafael Correa for the Lago Agrio plaintiffs, the “judiciary now lacks the necessary independence and institutional stability to adequately adjudicate highly politicized cases.”[112]

Both Ecuador and the Aguinda plaintiffs sued in federal court in New York seeking to stay the BIT arbitration. However, Judge Sand found, without ruling on the merits, that Chevron’s claim that it was being denied due process in the Lago Agrio litigation presented an arbitrable issue, and declined to issue a stay.[113] The Second Circuit affirmed.[114]

In February 2011, days before the court’s decision in Lago Agrio, the arbitration panel in The Hague ordered discretionary interim measures directing Ecuador to “take all measures at its disposal to suspend or cause to be suspended the enforcement or recognition within or without Ecuador of any judgment” against Chevron in the Lago Agrio lawsuit, pending further order by the panel.[115] In January 2012, the panel confirmed and re-issued the order as an interim award,[116] and in February 2012, the panel issued a second interim award ordering Ecuador, “whether by its judicial, legislative or executive branches,” to take “all measures necessary to suspend or cause to be suspended the enforcement and recognition within or without Ecuador of the judgments” by the Lago Agrio court. The arbitral panel’s order was made “strictly without prejudice to the merits of the Parties’ substantive and procedural disputes,”[117] notwithstanding the stronger language. Eleven days later, the arbitral panel ruled that it has jurisdiction to hear Chevron’s claims and proceed to the merits phase of the arbitration.[118]

In response to Chevron’s allegations in the BIT arbitration, Ecuador has emphasized that the lawsuit in Lago Agrio is a private litigation between private parties, and characterized the arbitral claims as an “attempt to ‘transform what is fundamentally a private environmental dispute into an ‘investment dispute’ against a sovereign.’ ” In response to the company’s allegations that the Lago Agrio litigation has been tainted by fraud, Ecuador accused Chevron of “attempt[ing] to divert attention from the demerits of [its] case ‘by cobbling together a list of inflammatory allegations’” that relate to the Lago Agrio plaintiffs, rather than Ecuador.[119] Ecuador further maintains that the settlement agreement operated only to release Chevron from claims by Ecuador and Petroecuador, and that Ecuador expressly rejected a suggestion from Texaco during the settlement negotiations that the release be extended to claims by residents of the Amazon region.[120]

In response to Chevron’s allegations of systemic deficiencies in the administration of justice, Ecuador’s Attorney General, in a statement to the arbitration panel, acknowledged that difficult problems exist, but maintained that Ecuador is working to correct the deficiencies and is making progress, and that the judiciary is independent. He accused Chevron of fabricating a crisis in the administration of justice because it does not want to litigate against the Lago Agrio plaintiffs, and argued that the relief sought by the company—to “close” the case in Lago Agrio—would amount to an unconstitutional violation of the independence of “the legal system.” He did not deny that the current government has made public statements in support of “the people of Lago Agrio,” but denied interfering with the judicial process in the litigation. He accused Chevron of attacking the Ecuadorian State, and said that the company’s “offensive without limit” began in 2003—when Ecuador informed Chevron and representatives of the plaintiffs that it would remain neutral in the litigation and “refused to interfere . . . to disqualify” the case—and that it has required Ecuador to respond, with limited resources, to repeated legal cases and a public relations “machine” that “every year work[s] in the corridors of the American Congress and also in the offices of the representatives of commerce of the United States looking to cancel the [trade] preferences that Ecuador enjoys…, with the intention of [pressuring] the Government to intervene in the case of Lago Agrio in favour of Chevron.”[121]

In January 2012, Ecuador’s Attorney General forwarded a copy of the BIT panel’s January 2012 interim award on interim measures (ordering Ecuador to “take all measures at its disposal to suspend . . . enforcement or recognition” of any judgment against Chevron) to the Lago Agrio Court. The appellate (sole) division of the court ruled that there is no lawful measure that the court can take to suspend the Lago Agrio judgment, and that it cannot “simply ‘obey’ ” Chevron or the arbitral panel, but rather must act within the parameters of the law. Although the court stated that it had thus complied with the arbitral order (but found itself without any legal instrument to suspend recognition of the Lago Agrio judgment), it also observed that the BIT arbitration presents a potential conflict between international investor arbitration norms and international human rights norms. The court concluded that under both international and domestic law, international norms to protect investments and an arbitral order may not be applied to override human rights norms, and in the case of a conflict, human rights norms must prevail.[122]

Chevron moved to revoke and amplify the ruling, but the Lago Agrio court ratified its prior decision and reaffirmed that—under Ecuadorian law, based on international commitments and constitutional law—the obligations of the state pursuant to human rights norms take precedence over international commercial obligations and the authority of an arbitral panel. The court again stressed the need to act in accordance with the rule of law, and concluded that the most recent arbitral order directing the court to take all “necessary measures” to prevent enforcement of the Lago Agrio judgment conflicted with the court’s obligation, as part of the State, to guarantee effective judicial remedies. The obligation to act “outside of the law” to take special measures to achieve a certain outcome in this particular case would discriminate against the Lago Agrio plaintiffs and restrict their rights, in violation of international human rights norms that protect the right to equal protection of the law and the right to judicial protection and remedies. The court thus refused to suspend the Lago Agrio judgment and instead formally declared that the judgment is legally enforceable, and ordered the transfer of the litigation record to the National Court of Justice in Quito, in custody of the National Police.[123]

Chevron’s lawsuit in New York followed extensive discovery proceedings in the United States, [124] which gained force after the release of a documentary film about the Lago Agrio case in 2009. The film, Crude, was solicited by the New York lawyer who manages the case for the plaintiffs, Steven Donziger. The film crew shadowed the plaintiffs’ lawyers for three years, shooting some 600 hours of footage. The initial version of the film showed an expert who contributed to what was supposed to be an independent, comprehensive assessment of the alleged damages for the Lago Agrio court meeting with plaintiffs’ counsel. The images of the expert were subsequently edited out, but not before Chevron saw them.[125]

Chevron used that scene, and others, to get a discovery order compelling the filmmaker, Joseph Berlinger, to produce all of the outtakes (raw footage that does not appear in the film).[126] The company argued that the outtakes were “more than likely relevant” to Chevron’s claims and defenses in the Lago Agrio lawsuit and BIT arbitration, and that they would likely “depict [the Lago Agrio] plaintiffs’ counsel’s interaction with at least one supposedly neutral expert”, “plaintiffs’ improper influence on the Ecuadorian judicial system,” and “plaintiffs’ attempts to ‘curry favor’ with [the government of Ecuador].”[127] Chevron also subpoenaed environmental consultants, and even lawyers, who were involved in the case to give deposition testimony and turn over documents. The discovery proceedings are ongoing, but already number in the dozens.[128] They have resulted in at least fifty orders and opinions from federal courts across the country, and have been described by the Third and Second Circuits as “unique in the annals of American judicial history.”[129]

As a result of the discovery, Chevron gained access to an extraordinary amount of material, including Donziger’s litigation files and hard drive.[130] Chevron argued successfully that the material it sought was not protected by attorney-client privilege because it had not attached or because it was waived.[131] Among other disclosures, the company found evidence that the legal team for the plaintiffs ghostwrote most of the comprehensive damages assessment that had been presented to the Lago Agrio court as the work of the “independent” court-appointed expert (Richard Cabrera). Chevron also found outtakes from Crude showing Donziger stating that all Ecuadorian judges are “corrupt” and explaining:

You can solve anything with politics as long as the judges are intelligent enough to understand the politics . . . . [T]hey don’t have to be intelligent enough to understand the law, just as long as they understand the politics.”[132]

The company also found evidence that Donziger and Frente had made undisclosed agreements with funders and third party investors in exchange for interests in the Lago Agrio judgment.[133]

Chevron’s complaint in the New York lawsuit names fifty-five defendants. They include Donziger; Frente and its Ecuadorian lawyer, Pablo Fajardo (who is also counsel of record for the Lago Agrio plaintiffs); Frente’s founder, Luis Yanza; an environmental consulting firm that worked closely with Donziger (Stratus Consulting) and two of its managers; and the Lago Agrio plaintiffs. The complaint also alleges culpable conduct by a number of non-parties, including Kohn, Swift and Graf, the U.S. law firm that initially financed the Lago Agrio lawsuit and was co-lead counsel for the plaintiffs in Aguinda v. Texaco,[134] and the California-based NGO Amazon Watch, which works closely with Frente and Donziger.[135]

The complaint asserts substantive and conspiracy claims under the Racketeer Influences and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) against all of the defendants except the Lago Agrio plaintiffs, based on allegations that the Lago Agrio case is a “sham” lawsuit and part of an alleged criminal enterprise to obtain a settlement or judgment from Chevron through fraud and extortion. The complaint also includes claims for civil conspiracy (under state law) and fraud against all of the defendants, as well as a claim against Donziger and his law firm for violation of the New York Judiciary Law. In addition to money damages, Chevron sought a judicial declaration that the Lago Agrio judgment is non-recognizable and unenforceable, and an injunction barring any attempt to enforce the judgment in the United States or abroad.[136]

Initially, U.S. District Court Judge Lewis Kaplan issued a preliminary injunction enjoining the defendants from taking any action to enforce the Lago Agrio judgment outside of Ecuador pending a final determination of the New York lawsuit. In a lengthy opinion, Judge Kaplan concluded that Chevron would likely show that the Ecuadorian judiciary is incapable of producing a judgment that New York courts can respect because the courts there do not act impartially, and additionally, that there was “ample evidence of fraud” in the Lago Agrio litigation that had not yet been contradicted or explained.[137]

The Second Circuit Court of Appeals, however, vacated the injunction and dismissed Chevron’s claim for declaratory and injunctive relief.[138] The appellate court did not rule on the merits of Chevron’s allegations, but rather held that the procedural device that the company chose is unavailable because New York’s Uniform Foreign Country Money-Judgments Recognition Act does not grant a cause of action to putative judgment-debtors to challenge foreign judgments before enforcement is sought. The judgment recognition statute allows a party to challenge the validity of a foreign judgment when a judgment creditor seeks to enforce the judgment in New York, but it cannot be used preemptively to declare foreign judgments void and enjoin their enforcement. The Second Circuit explained that the judgment recognition statute was designed to provide a means for foreign judgment creditors to enforce their rights in New York courts, and that the act includes defenses which allow courts to decline to enforce fraudulent judgments from corrupt legal systems. Nonetheless, those defenses are exceptions and they do not create an affirmative cause of action for disappointed litigants to enjoin enforcement.[139]

The Second Circuit based its holding on statutory interpretation, but seemed troubled by the global reach of the injunction and included a discussion of international comity in the opinion. The court found that considerations of comity provide “additional reasons” to conclude that the statute cannot support the injunctive remedy granted by the district court.[140] In enacting the judgment recognition statute, the Second Circuit reasoned, New York meant to “act as a responsible participant in an international system of justice—not to set up its courts as a transnational arbiter to dictate to the entire world which judgments are entitled to respect and which countries’ courts are to be treated as international pariahs.”[141]

Discovery and litigation on the remaining claims are underway.[142] The defendants reject the jurisdiction of the U.S. court over the Ecuadorian parties[143] and are contesting the lawsuit on a number of grounds. They have also accused Chevron of unclean hands in the Lago Agrio litigation, and in August 2012, Donziger filed a motion for leave to file counterclaims for fraud and civil extortion based on allegations that “Chevron has engaged in a coordinated scheme of intentionally false and misleading statements and extortion intended to harass and intimidate Donziger and eliminate the fruits of Donziger’s and the Ecuadorian Plaintiffs’ now nearly 19-years’ worth of legal efforts in Ecuador.”[144]

In November 2012, a group of forty-two Huaorani from five communities moved to intervene in the New York lawsuit in order to defend the Lago Agrio judgment and the rights and interests of the Huaorani in the judgment, by (1) opposing Chevron’s challenges to the validity of the judgment, and (2) asserting cross claims against Donziger and Frente. The proposed Huaorani intervenors seek to defend the integrity of the Ecuadorian judgment, but not any alleged misconduct by the plaintiffs’ legal team (including Frente) and their associates.[145]

The [Proposed] Answer and Cross-Complaint in Intervention alleges—on behalf of the proposed intervenors’ communities and family groups and the Huaorani people—that the judgment in the Lago Agrio lawsuit is based “in significant part” on injuries suffered by the proposed intervenors and other Huaorani, and that it “recognizes their right to benefit from the judgment.”[146] The cross claims against Donziger and Frente seek a declaratory judgment,[147] the imposition of a constructive trust,[148] and an accounting[149] to protect the Huaorani’s “significantly protectable interest in the Lago Agrio Judgment and their right to remedies as alleged and adjudged in the Lago Agrio [l]itigation.”[150]

The proposed Huaorani intervenors dispute the claims by Donziger and Frente to represent them,[151] but allege that, as a result of the defendants’ actions in connection with the Lago Agrio litigation and of the judgment consequently entered and affirmed on appeal, Donziger and Frente now owe a fiduciary duty to them, including, among other things, a duty to protect their interests in the Lago Agrio judgment and their right to remedies, a duty to notify the proposed Huaorani intervenors of the status of any enforcement proceedings and of any arrangements with third parties (including investors, funders, and/or the government of Ecuador) to receive or administer any proceeds from the Lago Agrio litigation, and a duty to remit to the Huaorani intervenors and other Huaorani (and their communities) their rightful portion of the judgment.[152] The proposed cross-complaint in intervention further alleges that Donziger and Frente have a conflict of interest with the Huaorani; that the decision to award control over the judgment monies to Frente was made without consulting the Huaorani; and that Frente and its lawyer, Pablo Fajardo (who also represents the Lago Agrio plaintiffs), have refused to provide the proposed Huaorani intervenors with meaningful information about the basis of their purported representation of the Huaorani and about their plans to use monies from the judgment to remedy harms suffered by the Huaorani.[153] The proposed cross-complaint also includes a claim for unjust enrichment. That motion is pending.

After nineteen years of litigation, the impact of Aguinda remains to be seen. If the Lago Agrio judgment is not overturned by Ecuador’s National Court of Justice, the question of whether it can be enforced remains. The likelihood of enforcing the judgment in a U.S. court is uncertain, but does not look promising at this time. The likelihood of collecting the judgment (or portions of it) in other countries where Chevron has assets is impossible to predict, as is the question of whether the parties will settle the case instead of litigating in courtrooms around the world. In May 2012, the Lago Agrio plaintiffs filed an enforcement action against subsidiaries of Chevron in Canada,[154] and the following month, they filed a second enforcement action in Brazil.[155] In November 2012, they filed an enforcement action in Argentina, and a judge for the city of Buenos Aires ordered the immediate freeze of “nearly all” of the assets of a local Chevron subsidiary “until the court rules on whether it will enforce [the Lago Agrio] judgment.”[156]

It also remains to be seen whether a victory in court—or settlement through the Lago Agrio plaintiffs’ lawyers—will obtain meaningful remedies for the Huaorani and other affected groups, or simply empower and enrich a new layer of elites and set back local struggles for environmental justice by promoting conflict, corruption, and cynicism. The decision to allow Frente to essentially control the monies awarded by the Lago Agrio Court reflects and reinforces the failure of the Aguinda litigation elites to allow meaningful participation by the affected Indigenous communities in decision-making processes and their apparent determination to, in the words of Huaorani critics, “speak for all but work only with a few.” The Huaorani and other Indigenous peoples who have suffered most from Texaco’s operations risk becoming symbols of justice without getting justice or adequate remedies.

For now, this new chapter in the litigation appears to be shifting much of the focus of the legal and political contest from allegations about Texaco’s misconduct to allegations of misconduct by the lawyers and activists who manage the Lago Agrio case, and from concern about the rights of the affected communities to the rights of Chevron.[157] The alleged misconduct not only has prolonged the litigation, but also seems to have tainted the credibility of the victims’ claims outside of Ecuador and may have jeopardized their right to a remedy. Moreover, it has eclipsed the situation on the ground—where environmental conditions continue to deteriorate, people’s rights are still being violated, and no one is accepting responsibility.

VII. The Intangible Zone and Conservation in Yasuni