NOTE: what follows is a lightly-edited transcript of a panel discussion held as part of the 54th Algonquian Conference, University of Colorado Boulder, October 21, 2022. Three panelists (Mary Hermes, Mary-Odile Junker, and Michael Running Wolf) joined remotely, and two panelists (Antti Arppe and Nora Livesay) joined in person.

Authors/panelists

Antti Arppe, University of Alberta

Mary Hermes, University of Minnesota

Marie-Odile Junker, Carleton University

Nora Livesay, University of Minnesota

Michael Running Wolf, McGill University, Indigenous in AI

Moderator

Alexis Palmer, University of Colorado Boulder

Overview:

Language technologies have become an important part of how we interact with the world, not only through voice-activated systems like Siri or Alexa, but also through interactions with people and information online, use of text-based interfaces on mobile phones and other digital devices, and engagement with the emerging technological landscape around artificial intelligence. Looking at the intersection of language and technology from another, related perspective, some researchers in computational linguists and natural language processing strive to develop tools to support the linguistic analysis of a wide range of languages, with many focusing on indigenous languages. Such technologies have the potential to help with projects related to language learning, language reclamation and revitalization, and language documentation and description. Today’s panel is convened to hear from experts in this area. Our panelists have worked both in academic contexts and, more importantly, directly with language communities. We thank them for sharing their experiences and insights, as we reflect on how language technology might (or might not) play a role in realizing the potential benefits of the International Decade of Indigenous Languages (“IDIL”).

Part One: Introductions

For this section of the panel, we have asked each panelist to introduce themselves and to discuss their projects, experiences, thoughts, and insights related to language technologies.

Alexis Palmer:

Good morning, everyone, and welcome to our second panel for today. My name is Alexis Palmer. I’m a professor of computational linguistics here at CU Boulder. I’ve been thinking about the intersection of computational linguistics and language documentation, revitalization and description since I was a young-ish Ph.D. student in 2006. We hosted a workshop on computational linguistics and language documentation[1], and this was where I first became aware of how complex this intersection is, how many different issues there are to consider, and how impossible it is to find some quick, easy way to develop all the language technologies that might be needed by all communities all around the world.

Today we have the opportunity of hearing from five experts on questions related to computational linguistics, language technologies and the IDIL. We will begin with introductions from our panelists, starting with Mary Hermes.

Mary Hermes:

Thanks, Alexis. I’m going to quickly tell you who I am, and I’m also going to tell you a little bit about the project I’m working on. So, Bozhoo, good to see all of you. I think we’re all in the space of trying to figure out what’s good in person and what’s good online. They both have affordances. And so that’s what I’m going to talk to you about specifically for the way I am approaching technology use as a tool right now.

I’m a professor of curriculum instruction at the University of Minnesota, but I live near the Lac Courte Oreilles reservation in Hayward, Wisconsin, where I’m a longtime community member, and I’m doing most of my stuff online these days. Since I don’t have a lot of time, let me give you a little peek into what we’re doing. I always try to make my work about research into practice. So we did a lot of documentation and then we made software.

The last project we did was the Forest Walks[2], and that was a documentation grant, using point of view cameras. I think some of you know of that. The project is intergenerational, with no agenda other than: what would people say in an everyday way in the forest? This is our attempt to connect to a bigger environment – a language is not words, or text, it is the whole context.

Building on the previous National Science Foundation (“NSF”) grant that funded the Forest Walks project, we wrote a Spencer Grant[3] with the aim of asking: how do we connect people to land and language, and what’s missing specifically in our community? We have good revitalization in our immersion schools, in our ceremonies; we hear language. We are still dispersed. Every community has a few people, and that’s it. So technology is a really important tool. We also know that a lot of our young people use video games as their main storytelling tool, but we’ve never produced one. We watch other people’s games of conquest and about nature being conquered. And this is exactly not the epistemology we are after in our language.

So we decided to make a point and click video game that’s all in Ojibwe. This is our best attempt to break into a domain that is home, family, fun, and very much youth driven. We are about one year and three months into a five-year project, so we’re still in process from pre-production to production. It’s a big leap out of academia for me to be a producer of a nine-person team actually making a real video game! We have a million-dollar budget that we leveraged from a literacy grant, and we have five years.

Our demo is not yet playable, but it will be, and the game will be in Ojibwe. On the screen now we see our main character. She’s lost in the forest. She has a lot of challenges, and she will use Ojibwe and talk to everything — all the beings, not only the human beings — about how to solve puzzles. The game is mostly about dialog.

So for speakers who have gone through all available classes, and now are looking for a place to practice their Ojibwe, this is our remedy. Practice your especially difficult verb conjugations in an environment like this. The dictionary is in the corner of the screen. We plan to build some scaffolding; for example, when playing on easy mode, words from the current scene will come up in the dictionary.

Another part I want to demo is the role of cultural values in the game — you have to learn pretty quickly. You put out a (Ojibwe word), and if your pouch runs out, that’s Kinnick. Using your knife and other tools, you have to figure out how to refill your pouch, asking the Kinnikinick.

The last feature I’ll show you is a memory globe. This is about reclaiming actual sacred sites that have become dump sites. We have two such sites planned, and there will be a 360-degree picture with hot spots in it that you can navigate to learn about those sites. That’s the character’s secret mission.

One of the features of the software is that it is point and click; sound comes up when you click on one of the hotspots. For example [clicking on the image of a plant], we hear Mii wa’aw miskwaabiimizh, which means This is Red Willow.

So that’s our hope and dream: to make a little dent in the realm of entertainment and fun, the hopeful place where our young people really live, and to use technology to do it.

Palmer:

Thanks very much, Mary. Our next introduction will be from Marie-Odile Junker.

Marie-Odile Junker:

I am from Ottawa, Canada, teaching at Carleton University, and I am happy to join you from the land of the Algonquin Anishinaabe people. I started in the late 1990s to explore how information technology could support language preservation and maintenance in James Bay, Quebec. I have been extremely lucky my entire life to work with groups that had fluent speakers. I even worked with monolingual speakers of Cree, and I realize, hearing everything this morning about all of you involved in revitalization, that I have been extremely lucky, whether it was with East Cree, Innu or the Atikamekw, to be working with fluent speakers who are confident in their language skills.

In the late nineties I started looking at how information technology could help language maintenance. This led to the East Cree[4] website containing integrated language resources, including an oral stories database, grammar lessons, terminology creation, dictionaries, and all kinds of online resources. The site also includes a book catalogue which the

Cree School Board needed for distribution. East Cree people live over a very vast territory. As all of you in the Algonquian Conference know, the Algonquian people tend to be spread out, even if they’re in the same language group.

All along, I have been lucky to work with my colleague Marguerite MacKenzie, who had been involved with the Cree and Innu for a long time. Nothing is built out of nothing, right? I built on the work of other people before me. And one wonderful mentor for me was Marguerite MacKenzie. In 2005, we got a project — a community/university research alliance — where we started collaborating both with Innu in Labrador (Mamu Tshishkutamashutau) and in Quebec (Institut Tshakapesh). What’s special about the Innu is that you have Innu speakers who are speaking different colonial languages, divided by provincial boundaries: English in Labrador, and French in Quebec. They do not share the same colonial language, which kind of helps the Innu language to some degree, because if they are nearby, they can speak Innu together. Part of this project was very much inspired by the eastcree.org model and led to what is today the Innu-aimun[5] website. Also in 2005, I started the Algonquian Linguistic Atlas[6] that many of you are familiar with. At the end of 2021, the atlas had forty-two dialects, sixty-seven speakers and over 25,000 sound files. And we just finished reprogramming the admin interface software this summer. All those sites have public and admin interfaces, geared towards various users.

My methodology has always been to use participatory action research[7], and this has very much guided not only the linguistic documentation work but also the computing development work (for example, in systematically using agile programming). When you focus on research process, success is evaluated through the positive impact on speakers and the language, and you define the goals and methods with your partners. That also applies to computing tools.

One of the first lessons about computing I learned the hard way in 2000 was when I went with a fancy company that didn’t deliver. With my first grant on that topic, I later asked: why design a jet when all you need is a bicycle to go to the corner store? So, I learned this the hard way, like we all learn from our mistakes. I’ve been going at it ever since, looking for simple, elegant, cheap, sustainable, long-term solutions.

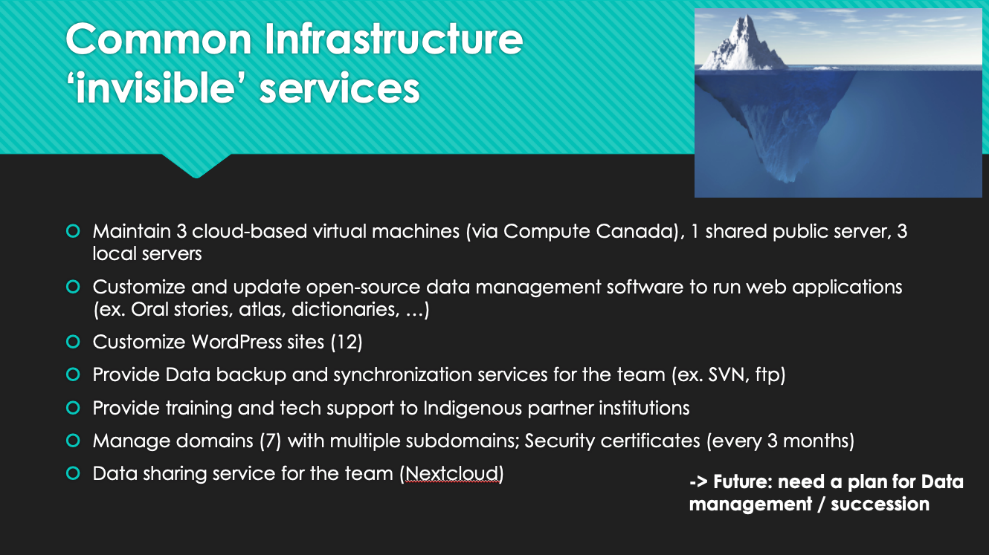

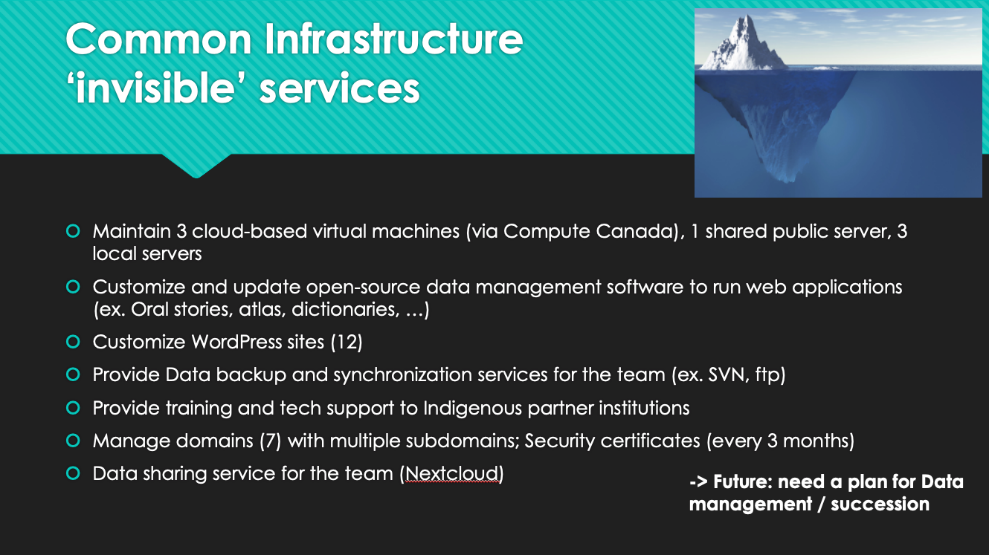

At this point, word was spreading and I had already started running workshops on grammar, and on dictionaries, involving people from neighboring groups. I started a project working on a common dictionary infrastructure, with twelve participating dictionaries, and the Atlas is the face of that project. We’re also sharing research methodologies and resources, and it’s been extremely successful. In its first year alone, the Innu dictionary had 11,000 word searches, and in 2021, it had over 250,000. These numbers leave out searches from offline apps (developed because they have bad internet service in Labrador) and printed books. So, all the participating dictionaries together now average over a million words searched per year. Of course, this is a service that I never intended to provide to the Canadian and general society in the long term. So, what you see is the tip of the iceberg. That’s what the common infrastructure  provides.

provides.

Then there are all those invisible services that are the bottom of the iceberg, and I’ll let you read through the list. It’s quite extensive. We have many servers, local servers, backup systems, twelve WordPress sites, data backup synchronization, training and tech support to Indigenous partner institutions, managing the domain with the security certificates. Not to mention how the need for cyber security has increased in the last year, which has really made our life difficult. Of course, you do not get funding for that part of the iceberg.

At this point, after twenty two plus years doing this, and now approaching retirement, I am really looking for a succession plan for data management and continuation of service to the language communities. And the need for continuity of services that you have been offering may be my main message to the IDIL. I would not have been able to develop this common infrastructure and run those services without the incredible help from my technical director Delasie Torkornoo who came to work for me fourteen years ago. Having the same technical director ensured continuity in the project.

Finally, to conclude, here [on the screen] are some computational tools that I’ve been dabbling in for the last twenty two years: syllabic converters (pre-unicode and after), databases (traditional and relational) with user interactivity, multimedia, verb conjugators, search engines, computer-assisted language learning. You can go to the different sites and see the lesson modules, multi-format creation, online and offline apps, and print scripts. We’ve used a lot of scripts, and lately are exploring more application programming interface (“API”) solutions. We’ve also lately been looking at a little bit of artificial intelligence (“AI”), although I am very concerned about what AI is trying to do. There is a lot of money coming for AI. It is data hungry, and vulnerable minority languages can be seen as free resources for AI applications and research, in the same way that forests, rivers and land which sustain Indigenous people have been and continue to be treated. AI doesn’t really know the context and the consequences of what it is doing. We don’t really know what the machine is doing when it learns. You all know the problems with artificial intelligence and I’m very cautious about that kind of development and we could talk about this in the discussion. Thank you.

Palmer:

Thank you very much. Up next, we’ll hear from Antti Arppe.

Antti Arppe:

Okay. I’m a native speaker of Finnish, which will influence many of my opinions. Looking at my first forty five years – I first got a masters of science in engineering from the Helsinki University of Technology, and then worked at the company called Lingsoft. This was a small language technology company that developed spell checkers and online dictionaries for the major languages of the Nordic countries — including Finnish. We licensed these to Microsoft as components.

After that, I got a PhD in linguistics from the University of Helsinki in 2009, and then I became a faculty member in Quantitative Linguistics. Actually, I was hired to be a statistical specialist at the University of Alberta and have been in that role for ten years. Already in my first year I was developing linguistic analytical tools for indigenous languages in Western Canada and the rest of North America, based upon a Sámi model. The Sami model was built by some Norwegians at Lingsoft who had been working on Norwegian tools that they then applied to the North Sámi language. At Alberta, we wondered whether this model could be applied to the North American context. Currently I’m a project director in the twenty first century Tools for Indigenous Languages project, funded by the Social Sciences Humanities Research Council [of Canada] for seven years, since 2019.

So what does Finnish have to do with my views here? As a bit of background, Finnish doesn’t have any gender. So I’ll be referring to people, him or her, in a mixed fashion, because my brain just doesn’t think that’s important. Finnish is morphologically complex. It’s not just the verbs, but also nouns and adjectives and other words can have many forms, a pattern which is somewhat similar to many indigenous languages. So I can build up quite a complex construction in Finnish – iloitsisinkohan teetätytettyäni lämmittävämmän takkini – which has a meaning something like Well, would I rejoice after I had had someone have someone have someone make my coat, that makes me warmer? So this Finnish context inspires or illustrates my viewpoints.

I should mention here, as a follow-up to this point, that we Finns were really fortunate in the 1800s that our political leadership decided that we should speak Finnish. If they hadn’t decided so, we might have ended up speaking Swedish or Russian. But one should also recognize that they basically had to build Finnish up from a colloquial language to actually the language of governance and education and the like. Even though it took a lot of a lot of time, that also has to be recognized. And it did help sort of having one’s own national borders and an army and Navy as well.

The overall focus of my current work is the 21st century tools for language project, and I’m working on that together with close to thirty people in North America and Europe. We aim to develop low-hanging-fruit software for indigenous languages, including intelligent electronic dictionaries that are easily searchable. We also aim to linguistically analyze databases of spoken recordings and written texts, build intelligent spelling and grammar checkers, intelligent keyboards, and intelligent computer-aided language learning applications. Things have changed in the last ten years, especially with respect to speech synthesis and transcription, and in fact, we actually now can deliver something useful [with those technologies]. That wasn’t really the case ten years ago.

When we use this sort of buzzword, low-hanging fruit, we mean tools that can be created swiftly based on existing linguistic documentation work of the sort that linguists here have done together with community members, and that some community members have done themselves. You don’t need large corpora, because these tools are based on the linguists’ and speakers’ understanding of the language. If you have a lexical database and descriptions of the [inflectional] paradigms, you can develop certain tools in a really short time. And these are intelligent in that they make use of language technology to deal with the complex word structure that’s typical for many North American languages – not English! There’s lots more happening than adding an -ed or -s to your noun or verb.

One thing I often want to illustrate is that the word structure in Plains Cree, or in other Algonquian languages, is just so expansive. In English we have five different forms for the word see, and it’s the same whether I see it or you see it, and if you see him or her. In Cree you would have three different verbs for the different types of actions and objects that you have. And then for the third case, if you’re actually seeing somebody animate/living, the verb marks both the seer and the seen. You also mark tense and aspect, such that the verb alone has something like over 500 core forms. And then you can actually have thousands more complex word forms if you add adverbs or auxiliaries to these verb forms.

With our team, we’ve done work on Plains Cree, and some with Woods Cree, and a number of other Algonquian languages. We have teamed up quite extensively with many other researchers. We also have some partners that work on Mohawk, one who works on Northern Haida, and one working with Arapaho. The tools we are developing in those partnerships are focused on building intelligent dictionaries, including the computational modeling of both word structure and phrase structure. Our flagship models so far are in Plains Cree, where you can search for phrases like “we are going to make you all sing” in English and get back an analysis of the Plains Cree translation ki-wî-nikamoh-itinân. The dictionary[8] shows the Cree word and also its connection the lexeme which means “to make someone sing”: nikamohêw. You can see [on the screen] a little robot icon next to the word which indicates that the form is not human-generated, but rather machine-generated. Search also works in the other direction – if you give the Cree word as input, you get back a sort of translation, and the dictionary covers many different forms of the words.

Something that’s been very important to communities is having spoken paradigms, so that they can hear how a word should find. For example, if you look up the Cree word for “helping someone,” we have human recordings for each of the inflected verb forms. We also now have the ability to make synthesized recordings of the pronunciations, since practically you can’t really record the roughly three million forms that would be needed – and that’s only covering the core forms for [Cree] nouns and verbs [in our online dictionary].

I’ll finish with the topic of intelligent keyboards, where we’ve recently started exploring word completion with a computational model. The goal is that, on a mobile device like this one here, you can have a keyboard for writing using a Cree-centered [Standard] Roman orthography. You can start writing a word partially and not have to bother with manual entry of diacritics. With the help of the computational model, we get suggestions on how this could be completed, and you can choose from among several options, which may be complete or partial word forms.

Finally, the most important point I want to make is that technology is never, never the solution. Technology is always, always an aid. It can be an important aid, but technology won’t solve the issue in any sense, and it will require a lot of time and effort and support.

Palmer:

Thank you. Wonderful. Next, we’ll hear from Nora Livesay.

Nora Livesay:

My name is Nora Livesay. I am from the Twin Cities, Minnesota area working at the University of Minnesota in American Indian Studies. I’m currently Editor of the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary.[9] I am a settler scholar. And one of the main points that I want to make as we talk about this, is that we have a lot of work to do with our institutions in terms of getting them to fully-fund and fully-recognize that it needs to be Indigenous linguists taking part in this work as well. So hopefully in a few years, I won’t be the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary Editor, and there will be an Ojibwe linguist in this position. Not that I don’t like my job, but I think that’s the way it needs to be.

My involvement in language technology came about in a very different way. In the late 1990s, early 2000s, I was doing web design — back when you had to code — and became involved with the Ojibwe Language Society, which was a community language table for people to practice the language. I did their phrase-of-the-day calendars, and their website for a while. Eventually I left journalism and the web design field, and did a master’s of Education with a tribal cohort, and started creating curricular materials for Ojibwe.

The first piece that we did — Leslie Harper, Debbie Eagle and I — was an audio children’s book to support curriculum on getting dressed. That project really got me excited about the potential to support the work that teachers are doing to help students — whether it’s young children or older adults — become fluent in Anishinaabemowin. I also worked with Dr. Mary Hermes on her Ojibwe Movies project, mostly on the back-end doing of the parsing, the thinking, the language help and other programming tasks. And then I began to work with Dr. John Nichols on the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary, where I believe my title was chief hand holder. But really what I did was try to take John’s vision of how the Ojibwe language works, and translate that into something that the programmers could understand. In the years since, I’ve worked with John on a number of different projects. We did some semi-automated parsing with the William Jones Texts project in FieldWorks Language Explorer (“FLEX”)[10] We also did some XML[11] programming to create a draft of an Oji-Cree dictionary that needed to be in three different Indigenous orthographies so that community members could review it.

About eighteen months ago, I took the position as Editor of the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary. In my current position, we’re working on a number of different technology-related projects. I just received a NSF grant[12] to digitize and make available curriculum and audio of first language speakers of Ojibwe from the 1970s. We’re going to transliterate the materials into the Double Vowel orthography (Fiero-Nichols)[13], where it will form the basis for an annotated corpus. And also make it more available. It’s all conversational materials, which is something that’s very much lacking. I’m also working with a computational linguist at the University of Minnesota to redesign the database of the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary. Because it’s been ten years, it’s time to look at what we want to do going forward, and how we can set things up to function better, not just for the users, but also for editors and maintainers. One of my goals is to eliminate the technical programming skills needed to edit the Dictionary.

We’re also launching an outreach project. The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary really wants to work with both users and key stakeholders, and ask them: “What do you want from the dictionary going forward?” Because as Antti said, a dictionary is just a tool. What we really want to do is support the work of the language community, and whatever they need to create more fluent speakers. I’ve also been doing some ArcGIS[14] work through an Indigenous mapping course that I taught spring semester, where we’re using ArcGIS technology to tell unheard Ojibwe and Dakota stories. That’s something that I see incorporating into the Dictionary at some point as well.

As I was thinking about this, one of the most important things that I realized is that the motivation has to come from what the community wants, and how we define community can change. So when I think of the Dictionary users — we have more than 40,000 monthly visitors– those visitors aren’t only in the areas where most people who speak southwestern Ojibwe live. It isn’t just Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and a little bit into Ontario. There are people using the Dictionary all the way east in Quebec and Labrador; there are people using the Dictionary in California, in Alberta, and in British Columbia. About forty percent of our Dictionary users are Canadian. As is true for many Algonquian languages, Ojibwe country was here before there was a U.S.-Canada border.

This can be challenging when you apply for funding, because you have to decide how to talk about this. Certain funders don’t care about things outside their borders, right? But another way to look at it is: when we look at who the people are that use the Dictionary — not just once in a while to look something up, but as a tool to teach, the people who are using it as a tool to learn — by going in and looking up a word, then looking at the morphological information there, and looking at what other words pattern like this that I can add to my vocabulary — those users tend to be a much smaller group of language activists, and they are tired. The pandemic has been hard on them because they are stretched so thin. And as we heard in one of the previous talks, that’s a really hard thing to be a not-quite-fluent level two speaker, to speak a language and be teaching it because your elders can’t do that. I think that there needs to be this larger conversation as well about we deal with the fact that the pandemic has really wreaked havoc on Indigenous people worldwide. For the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary, we’ve lost half of the speakers that we worked with in the last ten years, many of them in the last couple of years. The ones that we are still working with are in their eighties. They’re not going to be around for very long. We want to do as much as we can with them. But at the same time, I think we have to be looking at what do both the wider Ojibwe language community and also our language activists, what do they want? Because if we don’t address their priorities now, we may not be able to.

Palmer:

Thank you so much, Nora. And finally, I’m happy to welcome Michael Running Wolf.

Michael Running Wolf:

I’m Michael Running Wolf. Some things I’m interested in are technologies like Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality with voice controls, using AI for communities, specifically all the communities that we’re working with. And so, you know, trying to address access problems and the digital divide.

Critical to that, and something I’ve been primarily focused on, is AI. AI is cool. It’s the buzzword. It was brought up earlier and I agree with the sentiment. You can do some really cool things. I used to have a shih-tzu. His name was Wahhabi, which is Lakota, another Algonquian language– my father’s language. This [image on screen] is basically what he looked like, he was a little shih-tzu. So I asked DALL-E[15], which is a visual AI that can generate images, to make a shih-tzu wearing a Lakota headdress, and this is what I got. You can also ask other fun things like for prairie dogs wearing hats. I grew up in Birney, Montana. It’s a little village in eastern Montana.

You can do some really nice fun things with these AIs, but there’s also a problem. Machine learning has biases, and these biases can be seen here. For example, there’s an AI that can take a blurry image and then try to make it easier to see. And you can see it turns Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez into a white woman, turns Barack Obama, former president, into a white man, and Lucy Liu into a white woman. These are intrinsic biases to the AI. And furthermore, I fired up an instance of DALL-E for myself, and if you ask DALL-E, what do Americans at work look like, this is what you get: the usual, you know, they’re shuffling papers around this is what the AI thinks about how Americans work. [image on screen] Humans shuffling papers around on a desk, you know, basically true. I used to work in industry and similarly. Yes. What do Germans at work look like? [image on screen] Looks like Germans prefer paler colors, it’s a lot more monotone. You can see that they’re wearing suits and ties. But when you start to ask the question about other minority groups, you know, [image on screen] you get positives here for African-Americans that were similar and nothing crazy, nothing exciting.

But what happens when you ask the question, show me Native Americans at work, this is where you start seeing the problem of the biases intrinsic to AI. Now, it’s not like an AI engineer said, we are going to demonstrate that Native Americans at work are in residential schools or in boarding schools. But this is what the AI thinks about us. So we have fundamental problems of artificial intelligence. And it’s not that AI itself is evil. What’s going on here? What you’re seeing here is that the biases are in the data and these AI systems, these image recognition systems, are computed using pictures off the Internet. So if you have a Facebook profile and your picture is publicly accessible, you’re part of these databases. I found that I was, and some of my friends were. The AI isn’t necessarily itself biased, it’s simply a mirror upon the society who builds the AI. And you can see here, this is what they think of us, and this is actually what Western society thinks of us, because these are the images that you find if you Google “Native Americans at work.”

There is this broader question around artificial intelligence, which is very data hungry. In Western society and in industry, data is the new oil. We’re moving away from this concept of resource extraction to knowledge extraction, and this is going to be bigger and bigger. It’s already quite big. But think of this in the future, our very behaviors and our actions and our identities are commodities which can be exploited. We have communities that are trying to protect their very identity and trying to keep that within themselves, and maintaining the controls that a traditional knowledge keeper would have. But it’s also a resource, just like oil between the Northern Cheyenne tribe, the coal and natural gas. We now also have to contend with problems of wanting to extract their knowledge either for research (being legitimate), or illegitimate reasons, like google images or AI systems like DALL-E. And so how do we do it?

We all know most of us in here practice in some form the six Rs of indigenous research: relationality, respect, relevance, reciprocity, representation, and responsibility. And that’s where I come in. I’m a computer scientist. I’m currently doing my PhD at McGill in Montreal, and I’ve been working on AI and on the problem of how to use technology for indigenous communities in a way that’s positive. It needs to be a sustainable regenerative process and not just an extractive process, but we also have this problem of biases intrinsic to A.I. and what’s the solution?

My personal solution, and I’m really glad that Nora mentioned it as well, is that we need to do it, the indigenous need to do it. In July 2022, just a few months ago, I was in South Dakota with some of my partners, and we were teaching Lakota kids how to do artificial intelligence for the general goal of language reclamation. The kids went out into the fields and collected images of traditional plants, working with a local ethnobotanist. We’re collecting AI data and using industry tools. We didn’t treat them like babies and use Scratch or whatever, we used tools like jupyter, docker, github and unity. These are industry standard tools for training artificial intelligence systems and also augmented reality. Another part of the curriculum was teaching them Python, the computer language. One of the things we did was teach them turtle, and they loved it. Basically the idea is that you have this little turtle and you can make it draw things and you have to encode the instructions. And the kids just loved it. Within a week they had taught themselves Python and they were creating their first machine learning algorithms. And you can see that right here.

One of our students here is presenting their very own data classifier. And their very first AI Within five days of curricula, we had high schoolers producing Python AI. This one in particular. I think was about basketball. We picked out some datasets and said, hey, I want you to predict the success of something. They looked at basketball, football, the usual kind of stuff that kids might be interested in. They created their own classifiers where they could reliably predict the outcome of basketball games based upon parameters that you would typically look at. It’s the kids doing everything.

This is Mason Grimshaw, one of our teachers. And so we’re out there data collecting with for them to create their own AI. This is the AI code that they were working on and generated. And this is the AI that we’re using to do image classification. They collected pictures of traditional Lakota plants, and they gathered about five hundred images each. Then they created their own individual A.I., pooled the data, classified them into different categories, and then used standard and machine learning processes to create their own AI. They also generated confusion matrices for the different parameters and so forth for the Machine Learning Project. This is our instructor, Sean Shoshi. He’s a machine learning research scientist and he’s also one of my partners on building automatic speech recognition for polysynthetic languages for the Wakashawn languages in the Northwest, where I focus my research.

Knowledge is power, but to make it more palatable for the kids and more tangible, I also wanted them to be able to take home a phone with their app and show their grandma what they did. So, after collecting the data, learning how to train their own model in Python, and building the whole thing, they embedded their AI model in a mobile application using unity. And then they could take that application and show their friends, you know, we need to get this. We need to change the narrative on the communities, this is something that we can do. This is something that we should do, and something that we need to do. AI And so we put tools in kids’ hands and they can go around and spread the word.

It’s possible that I’m the kind of kid from the res, from Eagle Butte and from Gross Butte who can just do this and actually build their own systems. We have them do something tangible. So we got grants, got them laptops, and there they are, digging through their phones, showing what they built. Thank you.

Palmer:

Thank you so much, Michael. That’s super exciting to see.

Part Two: A Conversation with the Panelists

Palmer:

We now want to move into a conversation among the panelists. Part of the overarching goal of this conversation is to address two high level questions:

- How can language technologists support the aims of the IDIL?

- How can the provisions of the IDIL be brought to bear on language technology development?

Along these lines, there are five questions I hope we might discuss, though I don’t know if we will manage all of that in 30 minutes. There’s a lot to say. Here are the five questions we have prepared:

- What kinds of language technologies are of most interest to you? Do you, and how do you, offer tech support to the communities you work with?

- What kinds of barriers to developing and/or deploying language technologies have you encountered, including obsolescence[16]?

- What could the computational linguistics / language technology communities do to better support the needs and interests of language communities?

- Many past developments in language technologies have been projects that are specific to a particular language or small group of languages. Many others have tried to develop solutions that may work for any language. What are your thoughts about this choice between language-specific projects and higher-level standards/solutions? How about APIs as a way to avoid re-inventing the wheel?

- What about capacity building for technical skills?

Many of these are themes that have come up earlier this morning. So I’ll just turn things over to our panelists, but maybe we can start by talking about what kinds of language technologies do you think we should be focusing on? Or is there even a single answer to that?

Livesay:

I actually think that there’s not any one specific language technology that we should be working on. Instead, for each technology, there are a number of questions that we have to address to determine if it is a technology that should be used. The first being, is it is it something that’s going to support the community? Does it support the language community’s goals? Will it help our second language learners becoming fluent in their language?

Another key question one is how sustainable is it? Technology changes so fast. Some of this goes back to the classic Bird and Simons article on data portability.[17] But if you make something, is it sustainable? How long will it last? And what happens when devices change or versions change? Can you repurpose the data in some way, or do you just have to start over?

Arppe:

So the question is what sort of language technology are communities asking for? Actually, when you engage with the community first, they are not asking for language technology, and in particular are not asking for the very latest and state-of-the-art language technology. They are often actually hoping for support in the development of general language learning applications, or online dictionaries or text collections. These don’t really necessarily involve language technology at all, but rather require regular programming [work]. And then from an academic perspective, there’s a bit of a challenge there.

One element that communities are asking often is that they would like to see speech included as much as possible. For instance, the Maskwacîs Education School Commission wants to see that the younger people would actually know how to speak Cree [as it is spoken in Maskwacîs]. That’s been a paramount thing of importance to them, with less concern about how to write a particular form.

I am wondering whether there might be a bit of influence in English being the majority language and possibly influencing what people think is possible, and they might be expecting something that is done for English that requires large corpora, let’s say [neural network based] machine translation. That is not possible for most indigenous languages. But then folks might not be actually expecting something that could be done that’s based on rule-based technologies that could allow for, let’s say, this sort of partial word completion that I just described – that doesn’t require a large corpus. So English might be misleading.

Palmer:

Mary, did you have something you wanted to add also?

Hermes:

Thanks, Alexis. It’s really good to see everyone, old colleagues and friends and new. And I appreciate this panel very much. I guess I love what Nora said. Let the community lead.

But I do think there’s a role for us who’ve been working in this in-between space between technology and pedagogy and language, because I think sometimes people want a silver bullet and they don’t know. Maybe they don’t have the time to know all of what’s available. So I also want to say I agree that this panel is very diversified in the kind of technology things we’re doing. And if they’re all just tools, why not have them all? A bigger toolbox, more tools, different strategies. I think it’s so important. But I did want to put a pitch in for thinking about whether we are replicating the technology of translation of an English base? All those things that, you know, I see happening in a lot of the language software that some communities are putting an awful lot of money into. And I think that’s one thing we could sort of weigh in on. Is this technology going to get you to a proficiency? Is it a step to get there, or is it something that’s so deadly boring you’ll spend millions on? No one will use it.

Junker:

Yes, my experience has been that I’ve always put people before machines so that machines were a tool. I actually had the same approach with linguistic theories, that they are there to help describe the data and not the other way around.

I want to say a few things about tech support, having been in this area now for over 20 years. And obsolescence. So, for example, I want to mention the Path of the Elder’s game that we developed at Carleton over ten years ago which then became completely obsolete. It was hard to find money to reprogram it. It’s a video game, so there are lessons to be learned about that.

There is never any money to fix the potholes on the street, but there is always money to build new streets. So, the difficulty with maintaining established good projects, is that you have to create new projects, and under the guise of the new project, try to fix the whole thing. Some systems are perfectly fine, and people really like them, but then they stop working on many new devices.

Another important thing is to build allies. Once you have a technology that is servicing people and helping, you need to build tech support into your grant proposals and include tech support and training of the technicians who serve the communities. I’ve had a long experience sending Delasie Torkornoo, my technical director, for example, to visit the Innu or Cree communities to connect with the technicians that work there. For example, we know by name the person who comes once a week in the Atikamek communities to fix all the computers. And we train them so that they know what to do, on what the language activists and the people supporting the language need. It can be as minor as installing the syllabic fonts and a proper keyboard or make sure the last update did not cancel the chosen settings. There is this incredibly invisible work that you have to do to support technology. So, obsolescence comes in three forms: (If I can paraphrase my dear Del) you can have obsolescence in design, obsolescence in technology, and even obsolescence in the users.

The users I worked with twenty years ago are not at all the same as the users we are working with today and their children and grandchildren. Right. So, the demographics are important to knowledge and experience. Training is a huge part of any development. And then if people are interested, like, Nora, if you want, we could show you all the admin interfaces we had for two different dictionaries with the various users. We’ve always made editing of the dictionary accessible to different types of users, and the maintenance of that is also an invisible part of the projects. People only see the dictionary that is published. I don’t think we should need to start with the technology. We need to start with the people, see what they need, and be aware that their needs evolve over time and depend on the different communities.

Running Wolf:

Yeah, I think everyone covered most things. These are live, they’re not standard industry practices. You have to make sure your technology is sustainable and economically capable of being reliable in the future. And you’ve got to make sure that you include maintenance in your budget.

So back to kind of the original question: what kind of technology do we need? I think I agree with Marie in that there’s a lot of investment and sparkle, like it’s really easy to get money for the AI right now, but it’s been overapplied. And there’s a lot of money to give to the XR, the metaverse and all that. But what we really need is some solid investments in the potholes, the transcription pipeline, the documentation pipeline, how is audio being recorded at a level that the community can sustain it themselves. You know, tools like ELAN[18] are very hard to learn – like I’m sure you spend a lot of time teaching people how to do all these different things —

Junker:

I’ve always used very simple tools, including never using ELAN because it’s not accessible.

Running Wolf:

Yeah, exactly. What we need is a consistent tool base that exports to Google Drive, exports to Dropbox, exports to wherever. I think we need fundamental tools that scale and are easy and sustainable. Yes. Because there’s a lot of money for building AI, and we do need to be with the AI community centered, but we also need basic tools. Just the simple stuff is actually too hard right now.

Junker:

I can add to this. For example, there are a few tools that I’ve used since the nineties, and I have to confess it’s not just the community members, it is also the linguists who struggle with them. So, in the Algonquian Dictionary Project, we’re supporting various generations of linguists. When we started, we had people who were very good at what they were doing who would not work outside of a table in Microsoft Word. Then maybe Excel. Maybe then Toolbox. Maybe. FLEX – forget it – nobody! Nobody can use FLEX. FileMaker Plus, only a few. A lot of people use Toolbox, and there I’m talking about tools for dictionary making that have stood the test of time. I never believed that in 2022 I would still be using Toolbox with some people. However, Toolbox was very easy to teach and use for the Atikamek dictionary that was completed last year, and my team, the team of Indigenous lexicographers, worked very happily in Toolbox. Now we have an admin interface for the online dictionary that is a relational database and everything, but I don’t think that the current generation of lexicographers will want to be trained on that. It’s going to be younger ones that will be comfortable with it.

Livesay:

I agree with what both Michael and Marie said, that there’s almost like two sets of technologies. And we need basic tools and interoperability between them. There are things that linguists need that would make it easier to do transcription, to do parsing and morphological analysis. There are things to make it easier to get analysis from field work into a database. And then there’s getting what community members want and need. For example, for the Dictionary, we could have community members contributing audio. If we do some improvements to the back end, can we have community members with more experience do some editing and suggesting? We’re talking about a different set of tools that need to be easy to use, so that you can train people, and also keep maintaining the tools. And it’s the movement between all these systems that doesn’t necessarily exist in a standardized way.

Arppe:

To follow up on what’s been said by Marie and Michael and Nora, there’s funding for doing these really fancy newish things, and there might be funding for like a maximum seven years for that. But what actually is much harder to come by is instead that longer term maintenance of these tools, so that what’s been created is actually available to the community. Besides developing the technology, you also need that basic professional software development capacity to package these tools (for speech transcription, for example) so that regular people – linguists or community members – can actually use them.

We have employed on professional software developer, in similar ways as Marie-Odile did. So that is necessary, but it’s not so easy to get funding for that. The funding is needed to make such technologies useful and to keep them useful in the long term, but getting it is really a challenge. It could mean creative ways of getting funding from existing funding sources, or advocating for dedicated funding for the maintenance of what exists, rather than creating something new. But how exactly do we advocate for that? It’s really a challenge. But I think there should be pressure from, let’s say, the indigenous language community leadership, in terms of ensuring, when great things are developed, that they actually remain accessible and useful.

Junker:

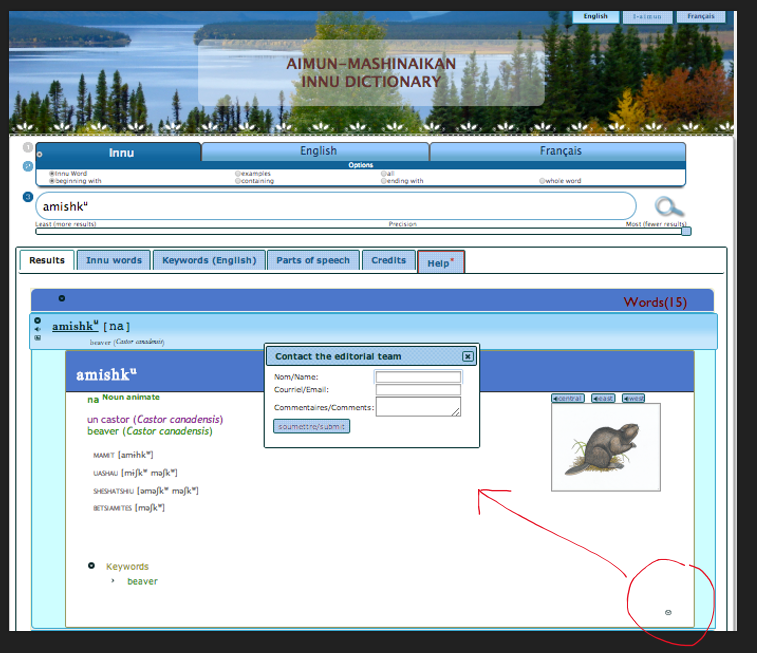

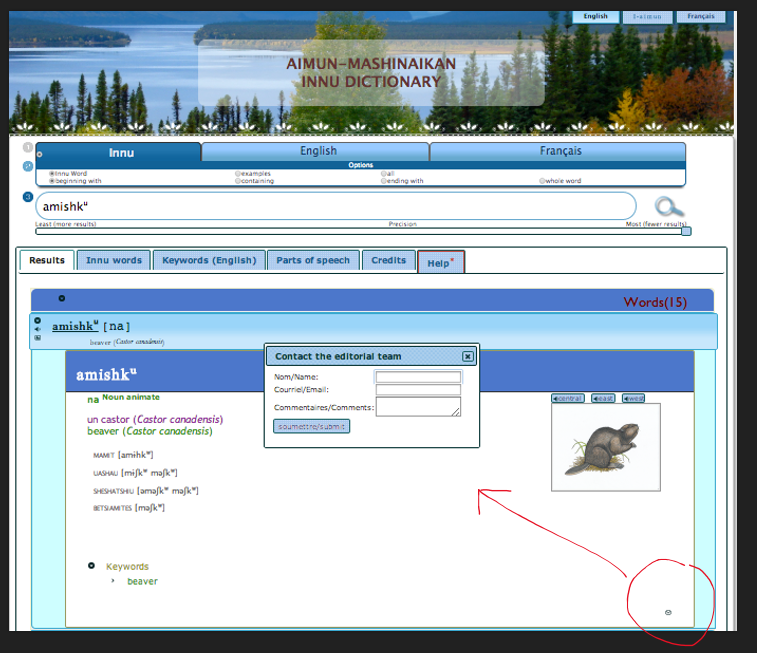

Can I add something to this? I would like to just show you a couple of slides and a couple of sound files about software and community involvement. [image on screen] The interaction with users is something that has really taken off for us since the pandemic. Something we started in 2012 was to have a tiny little mailbox icon at the end of each dictionary entry – what you see here is the Innu dictionary. With this, users of the dictionary can contact the editorial team with questions. Since we’ve been compiling, we’ve had over 400 really pertinent comments. This functionality makes these “living” dictionaries.

In April 2020 our editorial team was stuck at home. So, although we had already started working at a distance, we share screens in all those projects because people are far away and travel is expensive. We really got into Zoom meetings, and this is actually contrary to what you were saying in other communities. This has been wonderful to get elders involved. For me, it has been like teaching three courses on top of my regular job, with the Innu and the Atikamekw. More and more people want to come. They ask if younger people can come to watch the meetings, and one by one we go through the comments submitted to the dictionary. I think we had a presentation two years ago at the Algonquian Conference on that already, so you can watch videos online. During our Zoom meetings, we do record the pronunciation of words, and then we edit it and add them through the media manager to the dictionary.

The other thing is interaction with users. The terminology forum[19] is for all the Algonquian dictionaries that want to participate. Here you have an example of justice terminology, and when you connect, you can actually submit. If you don’t know how to write your words, you can record your pronunciation and submit the pronunciation of the words. And we have different level of user access, so we don’t we don’t get too much spam. This has been going on now for a while. There’s now a new course on Innu translation at the community college. Students in the class are going to train on this tool, as part of their translation degree, and they’ll have as a class project to develop technical words.

Palmer:

Are there questions or comments from the audience?

Audience member:

Thank you all for speaking. It’s been really interesting to learn more about this. Full disclosure, I’m not a linguist. I’m a law student. So my question is going to be more around that aspect, and maybe this is for people affiliated with universities. I’m just curious if you all have thought about the implications of hosting all of this information on a university site and how copyright comes in to that. How can we ensure that the legal rights to the language resources stay within the communities instead of being, you know, within the university?

Livesay:

I can tell you what we did with the Ojibwe Peoples Dictionary when we first developed it. Dr. John Nichols and I had a conversation with the librarian in charge of copyright because, like many universities, the University of Minnesota makes a lot of money on commercialization of its research projects. We wanted to ensure that the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary belonged to the Ojibwe people, so we set it up such that, while the University may provide the design of what the website looks like, the data is owned by the Dictionary and the Ojibwe people.

And as I set up the new NSF project this year, we have formalized this through our permissions. When we talk with and work with speakers, we ask them to give us a Creative Commons license to put their language data in the Dictionary. They retain the rights to it, and they can say no. We have a number of set permissions, so that they’re able to choose what they like, and say no to what they don’t want. I think that’s a really, really important question as we look at more and more data. And I don’t want it ever to be the case where the University says “we own this data.” That would just be very, very wrong. And I think that a Creative Commons license works for us, as the Dictionary, to use the data. I’m not sure it’s the best or only solution.

In listening to the presentation last night, one of the questions that I wondered about is: if we start creating lots of things with technology, and we get funding with federal governments, oftentimes the funding comes with requirements that you do certain things. For instance, if you have a federal grant, work that is the product of a federal grant has to be public. Right. So as a linguist, when you’re working with a speaker, if they say something that is sacred or shouldn’t be public, we say, please, please tell us if you’ve said something like that, so we can make sure it doesn’t become part of the data. You have to take care to make sure it doesn’t become part of a project unintentionally.

But I don’t know… in the U.S., there aren’t very many universities that have really thought about Indigenous sovereignty in that way. I think Canada’s maybe a little bit further along in at least acknowledging that there is such a thing as Indigenous data sovereignty.

Palmer:

Any other comments from other panelists? I think this is a really important question.

Arppe:

Our starting point is that the data belongs to the people who provided it — the members of the language communities or the developers of the dictionaries. That’s the starting point. When we are dealing with language technology and applications, we make use of that [data]. It is important then that the code we develop is open source, so it’s publicly available. We make sure it is made available to the communities without cost. Of course, there’s the cost of the software developers and the academics working with that [code]. But there’s no additional cost on making that available now or later on. So that’s what I would say is the contemporary minimum requirement.

Livesay:

Yeah. And that’s important. Because if you create something in proprietary software, it might be great, but somebody’s going to have to buy it. And they shouldn’t have to buy it.

Arppe:

Yeah. Sometimes we are approached by some bigger software companies who want to get involved, and one of the concerns is that their involvement would mean the creation of proprietary systems. I’m pretty certain that neither communities nor academics would want that to happen.

Running Wolf:

I’m thinking back to the law student’s question. We should be friends because I used to work in big data and industry, and it’s not a technical challenge. Privacy is engineering, and sovereignty is engineering about nanoscale. You know, obviously, corporations are abiding by it all the time, but it’s technically possible. It’s not a technical problem. It’s a political problem. It’s a policy problem.

Here’s what I would ask you as a law student: I see a potential technical solution, that could start to pose systemic change. It would be some sort of data co-op, similar to a grocery co-op, where the communities who have data are able to retain ownership, and they’ve just granted license and access to the central body. The co-op itself doesn’t own the data. There are different technological strategies we could use, or the communities themselves retain the data. And then the co-op is simply responsible for the pass through of data. The co-op does security, it’s in charge of encryption, and it’s in charge of authenticating users. And the communities can have the different terminologies in here.

This data governance this is broadly what the field is called in big data, the different terminologies. And I would say that also data clearinghouse is in a terminology that basically would be an escrow service for researchers who want access to community data. They have to get permission from the community, whatever process that may be. For example, for the Cheyenne you need to get a tribal resolution done, or go through the historical conservation office. Then you come to the co-op and say, Hey I have permission. Once we verify through the community, we hand over the data.

Then we also need policy through the wrap-up, we need someone with your credentials to say: you need to agree to these licensing terms, this is what you can and can’t do with the data. You can’t take this data, run off, and sell it to Google. You’re only allowed to do what the community gave you permission to do. The user fills out a form to have access to the data, and then can conduct the activities described. And then on top of that, we’re going to charge you – you’re going to have to put into your grant to have access to my community’s data. So you put the data fee in as a line item in the grant, and some of those funds goes toward the co-op’s overhead cost for maintaining data access, building necessary apps, and so on. The overhead cost of accessing the data can then go toward, you know, maintaining the infrastructure, the basic maintenance of the roads and the potholes.

And also, if there’s any profit, like a co-op, it’ll go back to members. I foresee this model could potentially work, and it could be sustainable from a research perspective for linguists who don’t have the time and capability to build deep relationships with communities like we do. But they will also want to be able to do research, and so they can license and pay money to the community and pay money into larger infrastructure. The question kind of becomes, to you as a legal person, what kind of policy do we need? Is this legally sound? And can we actually ensure the sovereignty of our data partners, the communities themselves? It’s a policy question.

Palmer:

Thank you so much for that, Michael. We have time for a couple more questions from the audience.

Audience member:

So for very young linguists just coming into the field of documentation this is probably a broad question. But what are some essential skills or tools to be familiar with in technology, so that we can be effective at documentation?

Arppe:

In the last ten years, many tools and packages have been created that are available and actually quite useful if you know bit of python. At the very least, to know how to install and start libraries and programs and do the standard things. And if you know a little more python, you can craft these tools for your own purposes. So you don’t need to know exactly how to train neural networks, because these have been nicely packaged. But you still need some coding competence to run things on the command line to actually make use of these. There are a lot of tools for automated speech transcription that could explode your productivity, in terms of having the machine do the obvious parts of the work, and then you as a human filling in the hard parts. So — general python programing knowledge, and familiarize yourself with these packages, that’s something I’d recommend. Also there are all the additional language documentation tools, with ELAN and so on.

Livesay:

I’d start with GitHub. Learn some of the standard tools that are out there for science in general. Right. GitHub is just a collection of repositories where people put the scripts and programs they develop to make them available. You can find lots of python tools in different GitHub repositories.

I think that’s really good advice, and it’s something that we feel is important as part of linguistics. Part of our NSF grant is to create a technology course for young linguists. The idea is: ok, we’re learning the linguistics. Now, how do we make this happen out in the community, and what kind of tools should we be looking at? I know one course isn’t going to do everything, but there is a big need for us to talk to about how to how to fund these things, as many people have brought up.

One of the things that we haven’t talked about, and that we need to speak about, is land grant institutions. Land grant institutions are still profiting off the stolen lands of Indigenous peoples.[20] Land and language are so tied that, when you lose a land base, you lose language. For instance, the University of Minnesota has made billions on that, and continues every year to receive hundreds of thousands of dollars in a permanent fund for whatever they decide to use it for. We need to really advocate that that money needs to come back to support infrastructure and technology, both at the academic level to support the maintenance of tools that communities want, but also back directly to the communities to be a funding stream to tribal colleges and language activists. And we need to make it with the same kind of wording that was used to begin with. It says that, the University of Minnesota gets these funds in perpetuity. Any new agreement about the funding needs to be stated in the same way. It needs to come back to Indigenous people in perpetuity.

Arppe:

Another one of the major obstacles is that you have software applications like Microsoft Office or Google’s applications out there that actually only support major languages and make it really difficult to support the remaining six and a half thousand languages all over the world. When we develop all this sort of fancy technology on top of that, it takes an inordinate amount of effort to try to get our tools to work well within these applications. For Microsoft or Google, there is no business case for them to actually support smaller languages with applications like spell checking, for example. It would be worth exploring putting pressure from good [software] design communities for policy on software giants. And if you want to operate in North America, to have the privilege of making money, you should have a well-defined and well-supported API for other [language] groups. Groups developing tools for spell checking, searching, indexing in any of the other languages should be able to integrate these tools as part of word processing, spreadsheets, search and the like. And that [integration] is hard for academics to do. That’s hard for Indigenous individual language companies to do. But this could be something where we could put pressure by the national governments to make that as a cost of doing business, that you have to support this [facilitating the integration of Indigenous language components].

Palmer:

So Nora and Antii, I’m going to take these as your closing statements, and I want to ask for any final thoughts from our online panelists.

Hermes:

I guess I have one thing to say about the technology, and to the student who is a young linguist. That is that, you know, the intervention is also where are you recording and how, and could you be on land? Could you have an intergenerational conversation? These are difficult to record and would need different technology. But that’s what language revitalization needs. We need that intergenerational speech. We need to see how people talk when they’re moving, not, you know, a nice, clean narrative sitting down in a soundproof room.

Also, I have to make a pitch. My closing statement is that I am responsible for setting up an indigenous language material center at the University of Minnesota. I wanted you to know about it. We’re just getting going. I need people to help me on the board to think about this, to think about a co-op, a sharing co-op. Right. And also to look back to all the great materials that we have. You know, tribes have tons of videotapes of elders talking that have not been digitized. So even digitizing and then being able to share that out would be another service we could provide as a university. Miigwech.

Junker:

I just want to mention that not all of us work in big universities. While I’m grateful to Carleton University, the Algonquian Dictionary infrastructure has never been on a Carleton server. It was completely unaffordable. Compute Canada (now the Canadian Digital Research Alliance that provides free accounts to faculty members) made this financially accessible. When I used (cheap) commercial servers, I always made sure my servers were in Canada, not in the US.

But to the young linguists, I want to say basic code literacy should be part of the training of documentary linguists. You don’t need to code yourself, but you need to talk to programmers. So that’s what I would suggest.

And then for the funding, I think there are a lot of lawyers in the room and people in politics. I think the dissemination of funding is a real problem right now, for example, in Canada. Heritage Canada gives a little bit of money to many different groups and there’s no real coordination. Various Indigenous organizations apply for the grant in January or February, wait for 8 months, and receive the money in October, but they have to spend it before the end of March. It’s completely crazy. It defeats the purpose. It’s very, very hard for them. And then the reality is, we’ve been hopping from one grant to another. I’ve been lucky to be continuously funded. Like right now I’m working with Antti, so I’m going to do spell checkers, but also to continue maintaining everything else. So how — I’m sorry if I use a strong word — how far do you have to prostitute yourself to sell what already exists, perhaps with paid API in order to keep maintaining what the communities want? And you know, the communities are in that situation as well.

And here is something for the people in politics and law. If only all the different entities in Indigenous communities and academic institutions in general could work together instead of being rivals. So, unity, cooperation and talking to each other, listening to each other. Very, very important. These are my takeaway words.

Palmer:

Thank you so much. Michael, anything from you?

Running Wolf:

I think the big takeaway for me is AI is almost never the answer. Furthermore, technology is almost never the answer. The answer is working with your community partners and trying to understand their needs. But that’s not to say ignore technology. I think what Antii said earlier and what Nora said earlier. Learn Python, understand GitHub, understand these tools that are being used.

There is no silver bullet. There’s no technology that’s going to save the language. Humans are going to save the language. And save is also a strong word, too. But reclaim language, rebuild language, reinvigorate communities. Technology is not the answer. It’s not going to be some new bobble that’s going to stop working in that year. AI is like that. It’s short lived, and I would just say, be conversing with your partners in the community and also become aware of technology and be able to make intelligent decisions around your technology investments. And don’t be afraid to make mistakes.

Palmer:

Wonderful. I want to thank all of our panelists for taking the time to join us today and for a really engaging and exciting conversation. Thank you, Marie, Mary, Michael, Nora and Antii. And thank you all for being here in the audience.

- Texas Linguistics Society 10: Computational Linguistics for Less-Studied Languages, Univ. of Tex. at Austin, https://tls.ling.utexas.edu/2006/ (last visited Feb. 19, 2023). ↑

- See Mary Hermes et al., Everyday Stories in a Forest: Multimodal Meaning-Making with Ojibwe Elders, Young People, Language and Place, 2021 WINHEC: Int’l J. Indigenous Educ. Scholarship 267 (2021). ↑

- The Spencer Foundation has a number of grant programs, mostly focused on supporting research in education. According to the foundation’s website, they aim to investigate ways to improve education around the world. See generally About Us, The Spencer Found., https://www.spencer.org/about-us (last visited Feb. 22, 2023). ↑

- East Cree language Res., www.eastcree.org (last visited Feb. 20, 2023). ↑

- Innu-aimun Language Res., www.innu-aimun.ca (last visited Feb. 20, 2023). ↑

- Algonquian Linguistic Atlas, www.atlas-ling.ca (last visited Feb. 20, 2023); Marie-Odile Junker & Claire Owen, The Algonquian Linguistic Atlas: Putting Indigenous Languages on the Map, in State of the Art Indigenous Languages in Research: A Collection of Selected Research Papers 314 (UNESCO, 2019). ↑

- Marie-Odile Junker, Participatory Action Research for Indigenous Linguistics in the Digital Age, 319 Insights from Practices in Community-Based Research, at 164. ↑

- Itwêwina: Plains Cree Dictionary, https://itwewina.altlab.app/ (last visited Feb. 19, 2023). ↑

- The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary, https://ojibwe.lib.umn.edu/ (last visited Feb. 19, 2023). ↑

- FLEx- FieldWorks Language Explorer- is an open-source software tool for managing and analyzing linguistic data. See generally Fieldworks Language Technology, SIL, https://software.sil.org/fieldworks/ (last visited Feb. 22, 2023); FLEx is developed and supported by SIL International in Dallas, Texas, “a faith-based nonprofit organization.” Both FLEx and its predecessor, the Field Linguist’s Toolbox continue to be widely used by linguists doing field research. Both systems include support for building dictionaries, adding linguistic analyses to texts, and (to a lesser extent) exporting data for archiving or other purposes. See generally Field Linguist’s Toolbox Language Teechnology, SIL, https://software.sil.org/toolbox/ (last visited Feb. 22, 2023). ↑

- XML (eXtensible Markup Language) is a text-based format for representing structured information. Data represented in XML can be freely and easily shared and processed, without the limitations sometimes posed by storing data in proprietary formats, such as those used by some commercial database software tools. See generally XML Essentials, W3C, https://www.w3.org/standards/xml/core (last visited Feb. 22, 2023). ↑

- NSF Dynamic language Infrastructure – NEH Documents Endangered Languages (DLI-DEL), Nat’l Sci. Found., https://beta.nsf.gov/funding/opportunities/nsf-dynamic-language-infrastructure-neh (last visited Feb. 19, 2023). ↑

- The Fiero (or Fiero-Nichols) Double Vowel writing system for Ojibwe is one of several orthographies currently in use for writing Ojibwe. This system is one of several proposed orthographies using characters from the Roman alphabet to represent the sounds of Ojibwe. Some speakers instead use a syllabic writing system, where each character represents the sounds of one syllable. ↑

- ArcGIS is proprietary commercial GIS (geographical information system) software. GIS technology can be used for many purposes, including linking place names mentioned in stories to their geographical coordinates. Once linked, the software can be used to make maps for visualizing the places mentioned in the stories. See generally esri, http://www.esri.com (last visited Feb. 23, 2023). ↑

- DALL-E is a deep learning model trained to generate images from natural language prompts. DALL-E was developed and released by the company OpenAI, and at the time of writing (February 20, 2023) it is available for limited free use by any user, after registering an account with OpenAI. Aditya Ramesh et al., Zero-Shot Text-to-Image Generation in Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning (2021). ↑

- Due to the sometimes-breakneck pace of technological development, many technological solutions, particularly those involving software, are subject to becoming obsolete, once computer systems have developed beyond the versions that the technological solutions were originally developed for. Maintaining compatibility with new computer systems is a non-trivial enterprise. See generally Damian Tojeiro-Rivero, Technological obsolenscence: a brief overview, Do Better. (July 8, 2022), https://dobetter.esade.edu/en/technological-obsolescence-brief-overview. ↑

- See Steven Bird and Gary F. Simons, Seven Dimensions of Portability for Language Documentation and Description, 79 Language 557 (2002), http://www.language-archives.org/documents/portability.pdf. ↑

- EUDICO Linguistic Annotator (“ELAN”) is an open-source software tool for labeling audio and/or visual recordings with a wide range of annotation types. ELAN was developed at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, The Netherlands, and it has been widely used in many different contexts for capturing, documenting, describing, and analyzing language data. Peter Wittenburg et al., ELAN: A Professional Framework for Multimodality Research in Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (2006). ↑

- Algonquian Terminology Forum, https://terminology.atlas-ling.ca/ (last visited Feb. 20, 2023). ↑

- Kalen Goodluck et al., The Land-Grant Universities Still Profiting off Indigenous Homelands, High Country News (Aug. 18, 2020), https://www.hcn.org/articles/indigenous-affairs-the-land-grant-universities-still-profiting-off-indigenous-homelands. ↑

NOTE: what follows is a lightly-edited transcript of a panel discussion held as part of the 54th Algonquian Conference, University of Colorado Boulder, October 21, 2022. Three panelists (Mary Hermes, Mary-Odile Junker, and Michael Running Wolf) joined remotely, and two panelists (Antti Arppe and Nora Livesay) joined in person.

Authors/panelists

Antti Arppe, University of Alberta

Mary Hermes, University of Minnesota

Marie-Odile Junker, Carleton University

Nora Livesay, University of Minnesota

Michael Running Wolf, McGill University, Indigenous in AI

Moderator

Alexis Palmer, University of Colorado Boulder

Overview:

Language technologies have become an important part of how we interact with the world, not only through voice-activated systems like Siri or Alexa, but also through interactions with people and information online, use of text-based interfaces on mobile phones and other digital devices, and engagement with the emerging technological landscape around artificial intelligence. Looking at the intersection of language and technology from another, related perspective, some researchers in computational linguists and natural language processing strive to develop tools to support the linguistic analysis of a wide range of languages, with many focusing on indigenous languages. Such technologies have the potential to help with projects related to language learning, language reclamation and revitalization, and language documentation and description. Today’s panel is convened to hear from experts in this area. Our panelists have worked both in academic contexts and, more importantly, directly with language communities. We thank them for sharing their experiences and insights, as we reflect on how language technology might (or might not) play a role in realizing the potential benefits of the International Decade of Indigenous Languages (“IDIL”).

Part One: Introductions

For this section of the panel, we have asked each panelist to introduce themselves and to discuss their projects, experiences, thoughts, and insights related to language technologies.

Alexis Palmer:

Good morning, everyone, and welcome to our second panel for today. My name is Alexis Palmer. I’m a professor of computational linguistics here at CU Boulder. I’ve been thinking about the intersection of computational linguistics and language documentation, revitalization and description since I was a young-ish Ph.D. student in 2006. We hosted a workshop on computational linguistics and language documentation[1], and this was where I first became aware of how complex this intersection is, how many different issues there are to consider, and how impossible it is to find some quick, easy way to develop all the language technologies that might be needed by all communities all around the world.

Today we have the opportunity of hearing from five experts on questions related to computational linguistics, language technologies and the IDIL. We will begin with introductions from our panelists, starting with Mary Hermes.

Mary Hermes:

Thanks, Alexis. I’m going to quickly tell you who I am, and I’m also going to tell you a little bit about the project I’m working on. So, Bozhoo, good to see all of you. I think we’re all in the space of trying to figure out what’s good in person and what’s good online. They both have affordances. And so that’s what I’m going to talk to you about specifically for the way I am approaching technology use as a tool right now.

I’m a professor of curriculum instruction at the University of Minnesota, but I live near the Lac Courte Oreilles reservation in Hayward, Wisconsin, where I’m a longtime community member, and I’m doing most of my stuff online these days. Since I don’t have a lot of time, let me give you a little peek into what we’re doing. I always try to make my work about research into practice. So we did a lot of documentation and then we made software.